There is a flagrant imbalance between the war machines of Capital and the new fascisms on the one hand, and the multiform struggles against the world-system of new capitalism on the other. It is a political imbalance but also an intellectual one. Our first thesis is that war, money, and the State are constitutive or constituent forces, in other words the ontological forces of capitalism. The critique of political economy is insufficient to the extent that the economy does not replace war but continues it by other means, ones that go necessarily through the State: monetary regulation and the legitimate monopoly on force for internal and external wars. To produce the genealogy of capitalism and reconstruct its “development,” we must always engage and articulate together the critique of political economy, critique of war, and critique of the State.

The museum’s full-time guide is a friendly faceless blue robot named artu-kun—“Mr. Art”—whose belly is branded with the Pocari Sweat logo. Part of his job is to remind visitors that it’s okay to touch the artworks here, since they’re indestructible objects. I walk around the museum, photographing and touching the artworks. I stroke the cheeks of Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring, and I press my face against Klimt’s Kiss. But the closer I get, the further away they seem. Does it still count as touching if my touch is guaranteed to have no effect?

Framelessness is a dream fulfilled as we enter the regime of the minimal within architecture. This is where the aesthetic coding of this place starts to align with the values of car production and kitchen design more than it does with the notion of work or social exchange. The car is the place of individual fulfillment where luxurious materials are deployed towards the crude representation of desire. The advanced kitchen is also a place where cabinetry and appliances start to lose their handles, hinges, and frames. The car and the kitchen are the two legacy aspects of advanced modernism that carry individual desire and have the potential to be replaced. The building under consideration deploys the logic of the car and the kitchen in its aesthetic clues.

Plastiglomerate clearly demonstrates the permanence of the disposable. It is evidence of death that cannot decay, or that decays so slowly as to have removed itself from a natural lifecycle. It is akin to a remnant, a relic, though one imbued with very little affect. As a charismatic object, it is a useful metaphor, poetic and aesthetic—a way through which science and culture can be brought together to demonstrate human impact on the land.

But are the concepts of biopolitics, positive or negative, or necropolitics, colonial or postcolonial, the formation of power in which late liberalism now operates—or has been operating? If concepts open understanding to what is all around us but not in our field of vision, does biopolitics any longer gather together under its conceptual wings what needs to be thought if we are to understand contemporary late liberalism? Have we been so entranced by the image of power working through life that we haven’t noticed the new problems, figures, strategies, and concepts emerging all around us, suggesting the revelation of a formation that is fundamental to but hidden by the concept of biopower? Have we been so focused on exploring each and every wrinkle in the biopolitical fold—biosecurity, biospectrality, thanatopoliticality—that we forgot to notice that the figures of biopower seem to be inflected by or giving way to new figures: the Desert, the Animist, the Virus? And is a return to sovereignty our only option for understanding contemporary late liberal power?

The dynamics that led to the ascent of the Nazis and then to the Second World War are back. Contemporary nationalist parties are echoing what Hitler said to the impoverished workers of Germany: you are not defeated and exploited workers, but national warriors, and you will win. They did not win, but they destroyed Europe. They will not win this time either, but they are poised to destroy the world.

I would not say that Big Data is boring, but rather that it is truly suspicious, and we will have to transform this practice of Big Data. This is why the digital humanities haven’t risen up against this monstrosity. Many digital humanities projects are part of this paradigm. When you visualize the co-relations between hundreds of thousands of images, you are employing the same logic as the Big Data industry (albeit harmlessly) and you are exhibiting its aesthetics. This kind of digital humanities is reaching the end of a transitional stage. Data is by no means our “Big Enemy.” We should be aware of the history of data, which has been a subject in the humanities for a long time without being thematized. It is now time to enter a new stage by taking the question of data and the organization of data further. It seems to me that this has to be the task of the future “digital humanities.”

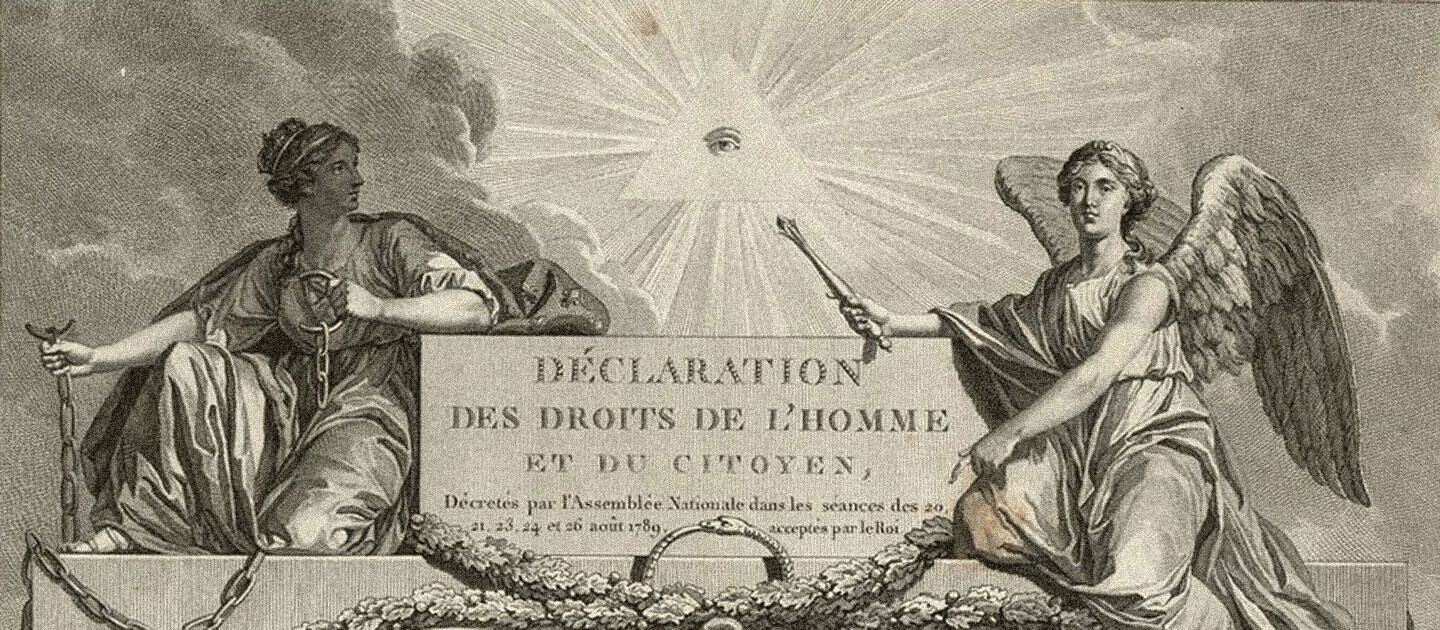

Does the activity of the citizen exclude the idea of representation? This position has been argued: whence the long series of discourses identifying active citizenship and “direct democracy,” with or without reference to antiquity. In reality this identification rests on a confusion.

The reappearance of fascism on the world scene requires a retheorization of nationalism. If the purpose of theory is that it allows us to see something safely, as Andrea Wilson Nightingale has argued—accompanying and guarding us like an old army general whose view of combat from distant elevated ground reveals patterns no fighting soldier could see—then the return of the past century’s most dangerous phenomenon indicates a theoretical failure at the heart of our strategic planning. Our inherited concept of nationalism has made navigating the lifeworld much more dangerous and difficult than it needs to be. It is either unfinished or poorly made.