“Spade with two handles”—

To fit the task at hand:

There can be no “private” industry.1

Joseph Beuys told his students: “You cannot wait for an ideal situation. You cannot wait for a tool without blood on it.” This was not to say a compromised tool can be made to serve all interests, but that a compromised tool can be weaponized to dismantle any interests. For art to integrate with society does not mean that art should serve the interests of society. Neither does it mean that art should serve the interests of art.

1. Disrupt Faster

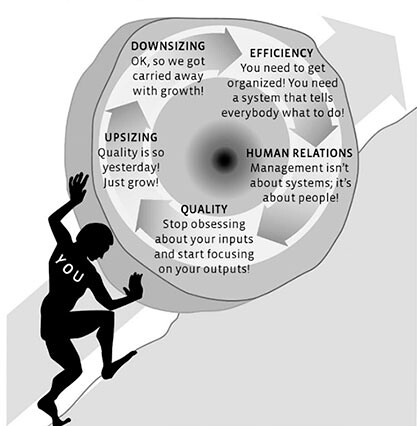

The idea that there is a rational, scientific basis to management advice can be traced to Fredrick Winslow Taylor, the turn-of-the-century mechanical engineer who was first to clock laborers on the job and devise strategies to make them move faster. Taylor’s name became synonymous with the early-1900s era of mechanization that idolized efficiency not only in the workplace but in all spheres of life. Nevermind the fact that none of Taylor’s research turned out to be scientifically sound—he fabricated numbers all over the place; his ideas, passed down through generations of management theorists (notably Frank and Lillian Gilbreth, Elton Mayo, and Peter Drucker) have shaped not only the entrepreneurial landscape of America but the very framework for how we understand labor relations within a system of “free” enterprise. The central tenets of Taylorist management that remain pervasive today are that managing humans is a numbers game and that instating bureaucratic procedures in the workplace is the (only) path to ensuring fairness—if not democracy itself. As philosopher-consultant Matthew Stewart writes, “Management theory is part of the democratic promise of America. It aims to replace the despotism of the old bosses with the rule of scientific law.”2

If there was one seismic shift in management theory over the last century, it was the revelation in the Fordist era that there’s more to managing workers than picking the strongest ones and goading them with financial incentives to lift things faster. Fragile emotions need managing, too. Psychologist Elton Mayo laid the groundwork for this idea in a series of 1920s experiments at Hawthorne Works, a Western Electric factory near Chicago. Essentially, these entailed temporarily improving the conditions in the factory: free refreshments, longer breaks, and even better lighting. With each of these changes, productivity rose—but miraculously, the researchers found that when the perks were removed one by one, productivity stayed almost as high. Mayo attributed this consistent productivity to a new sense of teamwork and mutual accountability the workers had developed simply by participating in the experiment.

Mayo wrote: “What actually happened was that six individuals became a team and the team gave itself wholeheartedly and spontaneously to cooperation … happy in the knowledge that they were working without coercion.” Of course the workers were not working without coercion—coercion was the whole point of the experiment—but the employees had been made to feel like colluders in their own exploitation, and therefore felt empowered and incentivized. According to Matthew Stewart, “The lessons Mayo drew from the experiment are in fact indistinguishable from those championed by the [management] gurus of the nineties: vertical hierarchies based on concepts of rationality and control are bad; flat organizations based on freedom, teamwork, and fluid job definitions are good.”3 In other words, rational and reproducible strategies could be used to forge the illusion of an organically arising sociality in the workplace.

In the age of the so-called knowledge economy, the importance of emotional management cannot be overstated. Emotional management today comprises the management not only of feelings (“my uniqueness is valued at the company”) but of lifestyle and corporate culture (“I’m part of something, I have cultural capital in addition to my stock options”). Perpetuating these feelings requires all the classic elements of affective manipulation that Mayo discovered, such as building teams and then pitting them against each other, undermining job stability, and distracting workers with nice lamps and free lunches—so there’s still plenty for the classic management consultant to advise about.4 However, the goals of effective management themselves have shifted. Beginning in the tech sector but now across the board, the goal is no longer Taylor-style efficiency but innovation. Simply put, it’s no longer about building the car faster, it’s about reimagining the car—disrupting the auto industry, auto-disruption. Innovation is still a type of efficiency, but it’s the efficiency of ideas.

Innovation requires not only mobilizing forces inside the company, but also predicting forces outside of it; if you’re trying to out-innovate consumers, you need to know them well. So a new type of consultant has emerged, with a new set of tools beyond blunt-instrument graphs and charts. Someone needs to come in and explain to management what the human public wants. Critical thinking, understanding human behavior, and access to subcultures/emerging markets are what qualifies you to be a good predictor.

By that logic, social scientists are therefore good at predicting things. Anthropologists are great at it. Designers turn out to be excellent. But who is the absolute best predictor? Hypothesis: artists. The tech sector in particular sees the artist as the original disruptor—the avant-guardist, or so goes the cliché. And more to the point, artists are relatively harmless, they need money, and it’s possible to convince them that working as a consultant is itself a disruption of their own industry, the art industry. Art needs to disrupt itself as much as any other industry—how else is it going to survive?

2. The Incidental Person

Artists have been engaging with the aesthetics of industry since it first appeared, but artists working as freelance corporate consultants represent a newer and more specific kind of engagement. The clear historical precursors to the artist-in-consultance are the multiple, well-known art and technology collaborations institutionalized in and around California in the 1960s and ’70s, notably LACMA’s Art + Technology Lab (1967–71, resurrected in 2013); the Experiments in Art and Technology (1967–77); and the Ocean Earth Development Corporation (1980 until today). These initiatives were many faceted, but they typically resulted in a rather limited number of outcomes.

In one outcome, the artist-in-consultance becomes a noncritical functionary (what Max Kozloff called a “fledgling technocrat”) engaged in the production of novelty spectacle. Many have argued that a good example of this is the PepsiCola Pavilion at the 1970 Osaka Expo that Art + Technology collaborators built—a smoke-and-mirrors aestheticization of technology.

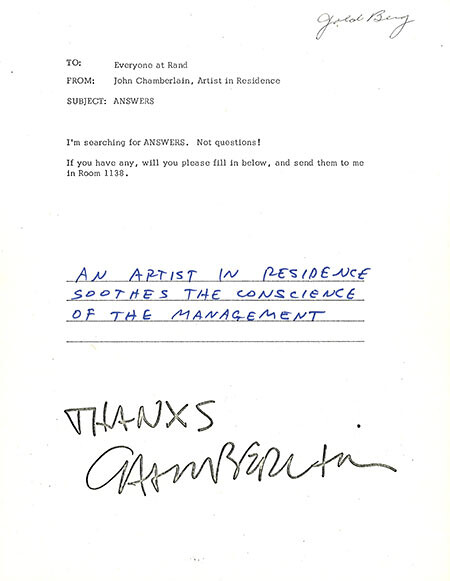

Another outcome is total antagonism. Take John Chamberlain’s residency at the RAND Corporation, organized by LACMA in 1970. Disappointed at the RAND employees’ “uptight,” “very 1953” attitudes towards any experimentation in the workplace, Chamberlain became determined to provoke them. He began screening his semi-pornographic movie The Secret Life of Hernando Cortez (1969) during employee lunch hour. After being asked to stop, he distributed a memo to all RAND consultants demanding “ANSWERS. Not questions!” The memo garnered responses like “the answer is to terminate Chamberlain” and “GO TO HELL MISTER!!”

A third outcome is no outcome at all. For instance, Ocean Earth’s decades of proposals and stalled collaborations have resulted in no concrete innovations. Cofounder Peter Fend would have it that his ideas are too threatening, rather than too implausible, to be adopted.

If I had to choose one of these outcomes, I like antagonism best—it hints at what actual “disruption” might look like and comes closest to dismantling the interests of both sides of the collaboration. However, it stops short of any real mutual engagement. During the RAND residency, Chamberlain and the employees essentially saw each other as ridiculous chumps rather than worthy adversaries.

Another artist-in-consultance model that, importantly, did not take place in California, managed to fluctuate between all three outcomes. As Claire Bishop wrote, this project seriously put forth the idea “that art can cause both business and art to re-evaluate their priorities,” or precisely what I mean by dismantling.5 This was the UK’s Artist Placement Group, or APG, founded by the artists Barbara Steveni and John Latham in 1966 and active until 1989.

Calling itself an “artist consultancy,” a “network consultancy,” or a “research organization,” APG arranged “placements” for artists within both public and private organizations for limited contract periods.6 Including the British Steel Corporation, the Ocean Fleets shipping company, and the Department of the Environment, selected host organizations allowed the artist to essentially roam free within their confines according to agreed-upon terms of service (rendered in remarkably authentic bureaucratic language in a huge volume of correspondence mostly written by Steveni, which is a body of artwork in itself). The projects ranged from art education, on-site installations, public outreach, and creative uses of technology to, in some cases, direct critical reflection on company management and policy.

Many of these collaborations dead-ended or became as superfluous or antagonistic as the above-mentioned projects. But a critical mass of them proved challenging, fruitful, and even tangibly beneficial to humans within and without the company. The success can be chalked up to the role, as carefully defined by APG, of the artist working in nonart contexts. Latham coined the term “Incidental Person” (IP) to account for this role.

The “incidental”—as opposed to instrumental—nature of the IP was due to her third-party status; to truly do the job, the IP had to be treated as any other professional in the organization, with the noted difference that the IP did not serve its interests. Latham wrote, “The work is fundamentally in the public interest and service, without being subordinated to corporate objectives as seen by the existing executives in corporation, government or department of government.”7

In other words, neither the organization at hand, nor the state, nor the APG, was the client of the Incidental Person. As Latham put it: “the artist as Incidental Person [is] a representative of the whole in the divided state State.”8 The IP was answerable only to the public good. I don’t mean public as in the public sector (as distinguished from the private sector), or the public as a market-target group; and I don’t mean good as in either charity or activism. I mean public good as Bishop meant it, as a way of providing third-party insight to reevaluate value systems in both business and art. Latham called this interest a “third ideological position”:

An Incidental Person takes the stand of a third ideological position which is off the plane of their obvious collision-areas. The function is more to watch the doings and listen to the noises, and to eliminate from the output the signs of a received idea as being of the work. In doing this he represents people who would not accept their premises, time-bases, ambitions, formulations as valid, and who will occupy the scene later.9

3. Vegan Burritos

Corporate philanthropy is an oblique kind of investment; the cost/benefit is not a straightforward calculation. For one, it’s an investment in employee morale, which is an important part of affective management. It’s also a marketing investment in public image (and the tax write-offs don’t hurt either). But most importantly, philanthropy is an investment in the general project of neoliberalism: the premise that unrestrained private profit is good for society at large. A tech company running an urban garden or an artist-in-residence program is living proof that the government need not intervene in big business; otherwise, as the author of a 1979 book called The New Corporate Philanthropy forewarned: “the government will inevitably be brought in to address problems.”10 So corporate philanthropy is an integral facet of the logic that public and private interests can be made to align—it makes the Venn diagram of public/private benefit look like a single unified circle.

The hiring of artist-consultants is rarely framed as philanthropy, but rather as an investment: they’re here to help us develop actual products and services; they’re here to enrich life at the office; they’re here to keep us on the cutting edge. Artists may do these things, but, like any type of philanthropy, they are also always an ideological investment in the ethics of the free market.

Many contemporary artists working with tech companies in the San Francisco Bay Area fulfill the same gratuitous roles as their 1970s predecessors. For example, the “novel-use-of-technology” model where artists become adorable functionaries dedicated to product development can be found at the software company Autodesk. After acquiring the how-to website Instructables in 2011, Autodesk launched an artist-in-residence program at its workshop on the San Francisco pier. Resident artists are brought in for a few months and given a moderate stipend and access to expensive software and machinery. “The logic was that by getting to know the people who are using technology in new, creative ways, Autodesk would be able to gather feedback to better respond to users.”11 Surely Autodesk does gather some ideas for how to make products more user-friendly by watching the artists play with the software, but the size of the artists’ stipend, as compared to an engineer’s salary, says everything about how much of a literal return on its investment Autodesk expects.

In another instance, Facebook employs what on the surface looks like a standard commissioning (patronage) strategy, inviting artists to create work for display on its Menlo Park campus—but the program is also framed as an artist residency, which is telling. This communicates that what’s being paid for is not only the object produced, but rather the artist’s whole brand identity and cultural caché, as well as their creative process. Facebook is commissioning the experience of having the artist on campus, wearing some hip hat and chatting with the technologists as they pass by the installation-in-progress on the way to the burrito stand.

This image is important. It’s an image of knowledge transfer going down. Artists ostensibly have a special type of knowledge by dint of being artists. That’s what makes them good predictors of the cultural tides in the first place. Preserving this assumption clearly behooves the artist—just as it behooves management consultants to preserve the idea that management is a science they have perfected over the ages. But unlike the management consultant, whose knowledge may be sacred but is only intrinsically good insofar as it applies to profit, the artist’s knowledge is intrinsically good because it supposedly transcends profit.

Through programs like these, artistic creativity is made indistinguishable from innovation. This reciprocally and tautologically makes sure that innovation remains an exalted process in its own right: innovation is an act of artistic creation, and is likewise therefore intrinsically good. Artist, management consultant: meet one another.

When art is placed on par with innovation, producing positive results just by being there, art is good in the same way that urban gardens are good, or Bringing Jobs to America is good, or a vegan burrito is good. Art is another aspect of lifestyle as a corporate-cultural value, and living proof that private profit as a form of governance is working out just fine.12 So are there any contemporary artists-in-consultance who amount to more than vegan burritos?

4. Splitting the Difference

There is something silly about creating “categorically ambiguous” art and deliberately leaving the ambiguities unresolved. Is this in order to give aestheticians trouble? How sixties can you get. You become a more significant artist in proportion to how ambiguous a borderline case you invent (ho-hum).13

Unsurprisingly, the least burrito-like situations are where everyone stops pretending that the artist isn’t working in some kind of service position, allowing the artist to go ahead and try to claim some kind of imaginative autonomy. For instance, calling oneself a designer rather than an artist helps lift the creativity-for-its-own-sake pretense that no self-respecting critical artist wants to bother with anymore, for the reasons mentioned above.14 But many still call themselves artists. Critical artists-in-consultance are fully aware that they are working on behalf of a client, and they own it—by flipping their corporate service work into the content of artwork for consumption in the art sector, and then flipping that critical success back into content that can be sold or reformulated for a corporate buyer, and so on. Examples of artists and groups doing this abound: if you want a list, you’ll find a lot on the 89+ roster. Rather than analyze specific examples, I’d like to propose some methods for evaluating this type of practice.

Much writing about contemporary artists working with/in the corporate sector gets stuck on the question of whether the artist can be both complicit and critical at the same time. In fact, this question has been tossed back and forth for at least the last fifty years in very similar terms. APG, for one, was constantly subject to accusations of total complicity—of ignoring class conflict, of naïveté, of “lack of political clarity.” Gustav Metzger went so far as to accuse the group of a type of collusion that could only lead to right-wing politics. In hindsight a causal relationship is hard make out, but it’s not laughable either; APG’s activity in the UK dovetailed perfectly with the Thatcherist era. Many also argued the other side; Jack Burnham eye-rolled in the October 1971 issue of Artforum: “Whether out of political conviction or paranoia, elements of the art-world tend to see latent fascist aesthetics in any liason with giant industries; it is permissible to have your fabrication done by a local sheet-metal shop, but not by Hewlett-Packard.”

In the debate over complicity versus criticality, the Metzger and Burnham routes are less common today. Instead, people usually end up arguing for some version of “both” or “neither.” This is partially for fear of sounding regressive (we’re post-post now, there is no outside, etc.), and also because it’s true: artists can have multiple clients, just like any consultant. In that sense, “complicit” is just a way of saying that an artist’s clients are primarily corporate, while “critical” is a way of saying that they are primarily from the art sector. The artist-in-consultance is always serving some combination of those two sectors. And here is the crux of the problem of the contemporary artist-in-consultance: it’s not that corporate consulting is service oriented, but that art-world criticality is too.

In his dissertation on the topic of artists who consult, Carson Salter writes of the different reactions to one artwork from the perspectives of art and tech: “[The artist’s] selection was read differently from various perspectives: conference attendees from the tech industry reportedly viewed the timeline as a celebration, where artist viewers saw it as an acerbic critique.”15 This is a perfect description of an artist trying to split the difference—art and tech become two sides of the same coin, both of which the artist is profiting from. At previous points in history, splitting the difference in this way might have been framed as a function of class conflict. “A Marxist … might well argue that the artist’s class position accords with that of the petty bourgeoisie, a group caught between two larger classes—the bourgeoisie and the proletariat—who oscillate in their loyalty but who generally serve the interests of the dominant class.”16 Trying to split the difference, according to this logic, always serves the interests of wealth.

In the best case, the artist-in-consultance who splits the difference can hope to be an “exorbitantly expensive and structurally disloyal hire,” as Matthew Stewart described what management consultants have largely become—earning money from an organization to criticize that organization and earning whatever one earns in the art world for the exact same activity. In the worst case, the artist-in-consultance occupies, to appropriate a term from David Graeber, a bullshit job. While in Graeber’s sense a bullshit job is a useless conglomeration of clerical, administrative, and service tasks that should probably have been made obsolete by technology but instead has been exacerbated by it, I mean it as an invented, superfluous occupation that, despite being “creative,” serves primarily to distract the subject it employs from any imaginative reevaluation of the system that has created it. It distracts the subject because it pays a living wage. If the private sector didn’t employ artists, or create crowd-funding platforms through which they could marginally employ each other, then there could conceivably develop a critical mass of unemployed thinkers who might demand that humans organize cultural support in a different way.

It is in any company’s interest to invest what amounts to a pittance in its grand scheme to support a working artist’s incisive critical projects—even outright damning ones. Ostensibly critical perspectives are typically exactly what the company is paying for. This mirrors the hiring of a management consultant, whose job it is to tell a company how naughty it’s been, and simply by being there provides the remedy for the naughtiness. Both types of consultant are elite outsiders with special knowledge, a knowledge that must be perpetually kept under wraps in order to stay special. Thus both types of consultant spend most of their time engaged in the act of justifying their presence, honing their critical tools but never actually using them to dismantle anything. Spending so much time honing your tools that you forget what you created them for—is this not the very definition of bureaucracy?

The artist-in-consultance serves corporate interests; this is not up for debate. Artists have found out how to likewise make consulting serve the interests of the art economy, and their own personal interests. The interest that is left unaccounted for here is that of John Latham’s abstract third client, the “third ideological position” that the Incidental Person was supposed to serve. I would propose bringing this third client back into the Venn diagram when evaluating the work of artists-in-consultance. That circle is very different today than it was in the Seventies, but it still exists—all it really needs to exist is an artist working in it. Rather than one of those apparently outdated terms like “the public,” I’ll just go for it and call this third circle: our dying planet. That is, all the humans and nonhumans at risk of extinction.

Preserving the integrity of all three circles as separate entities is important because it allows the existence of cases when private interest and other interests simply do not align. The goal of the artist-in-consultance should not be to force the interests of business, art, and the planet to overlap, but to preserve their misalignment at all costs.

“Joseph Beuys Titles for Sculptures,” in David Levi Strauss, Between Dog & Wolf: Essays on Art and Politics in the Twilight of the Millennium (Brooklyn: Autonomedia, 1999), 141.

Matthew Stewart, The Management Myth: Why the Experts Keep Getting it Wrong (New York: W.W. Norton, 2009).

Matthew Stewart, “The Management Myth,” The Atlantic, June 2006 →

Far from becoming obsolete or collapsing, management consultancy is diversifying and buying itself up. For example, longstanding management firms (McKinsey and the like) are supplementing their services by hiring entire creative groups as their own in-house consultants. Interview with Thomas Ulrik Madsen, May 16, 2016.

Claire Bishop, Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship (Brooklyn: Verso, 2012), 177.

Until the mid-1970s APG worked primarily with private companies but eventually shifted towards working with governmental organizations, reportedly because long-term contracts with corporations were hard to obtain. It is notable that APG was initially formed as a charity and only later incorporated into a limited company and eventually a multinational corporation. The shift to Ltd. status was partially due to the fact that it allowed artists to be paid a salary on par with other professionals.

John Latham, “The Incidental Person Approach to Government,” presentation at Joseph Beuys’s Free International University, documenta 6, Kassel, 1977.

As quoted in John Walker, John Latham: The Incidental Person—His Art and Ideas (London: Middlesex University Press: 1994), 100.

John Latham, “Artist: John Latham Placement: Scottish Office (Edinburgh),” Studio International, March–April 1976: 169–70.

Full quote: “It is also important to maintain and enhance in this country a pluralistic approach to our social needs, or the government will inevitably be brought in to address problems if other initiatives are not forthcoming. It isn’t enough to decry the expansion of governmental activity into every nook and cranny of public and private life. Surely the business community with its enormous intellectual, financial, and other resources can develop alternatives in the area of social problem-solving.” Frank Koch, The New Corporate Philanthropy: How Society and Business Can Profit (New York: Springer, 1979), 4.

Kelsey Campbell-Dollaghan, “How Startup Culture is Transforming Philanthropy,” Fast Company, April 11, 2013 →

I’m focusing on artists engaged in the private sector, though plenty work for governments and philanthropic organizations.

The definition of “ambiguity” from a dictionary written in 1973 by the members of the Art & Language group. Art & Language, “15: Ambiguity,” Blurting in A&L Online (Karlsruhe: ZKM, 2002) →. (Thanks to Carson Salter for unearthing this.)

In particular, “speculative design” increasingly provides a midway point between art and industry. According to California-based artist, designer, curator, and technologist Barry Threw, “More tech companies will be able to understand speculative design as a way to incorporate lateral and theoretical thinking, and this will open up a new role for artists.” Interview with author, May 24, 2016.

Carson Salter, Ambi_ Enterprise artworks, the artist-consultant, and contemporary attitudes of ambivalence, Master of Science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, June 2013, 68.

Walker, John Latham, 100-101.