Continued from “Freeportism as Style and Ideology: Post-Internet and Speculative Realism, Part I”

Freeports are large, tax-free storage facilities that are uniquely suited to housing works of art adapted to the demands of contemporary financial markets. Because of the dominance of these markets, “freeportism” can be understood to signify the conditions of representation, production, and distribution that correspond to this dominance. The successful freeport artwork requires a strong artistic brand, ample liquidity in the form of tradable artworks, galleries operating as market makers, and photogenic material objects that produce likable images on platforms such as Instagram and Facebook.

In the first part of this essay, I argued that the kind of art known as “post-internet” adapted to these conditions within a relatively short period of time—about five years—mostly by leaving aside its initial focus on web-related practices and processes. This transformation has turned “post-internet” art into a style of freeportism as such, much in the same way that, once upon a time, it could have been argued that Dutch still-life painting, with its depiction of worldly goods, was the style of the early financial market that flourished around the Amsterdam stock exchange founded in 1602.

To make the transmission from financial markets to artistic practices complete, an ideological framework was needed that supported the turn from discursive to material practices, from rituals of communication to objects and commodities, and from web-oriented and process-based artworks to shiny items provided in ample liquidity. The new brand of philosophical thinking called “speculative realism” offered itself as the ideology of freeportism and its associated modes of artistic production and circulation. Whether its appearance was a lucky coincidence, or whether both post-internet art and speculative realism are symptoms of the very same economic and technological regime, is open to discussion. However, both serve each other exceedingly well.

Speculative Realism and the Reality of Speculation

In 2013, “Speculations on Anonymous Materials” was the first major institutional exhibition to link post-internet art with speculative realism. Curated by Susanne Pfeffer at the Fridericianum in Kassel, the show was accompanied by a conference featuring several philosophers associated with speculative realism, including Markus Gabriel, Maurizio Ferraris, Iain Hamilton Grant, Robin Mackay, and Reza Negarestani.

The show rendered post-internet art as a visually and aesthetically coherent movement, through a materiality- and object-oriented selection of artists like Yngve Holen, Josh Kline, Katja Novitskova, Jon Rafman, and Timur Si-Qin, and by displaying the works in traditionally museal fashion. In so doing, the show contributed to canonizing post-internet art in a state that had already left behind its web-related roots.

At that point, post-internet art had shifted decidedly to the production of material objects. Galleries had come around to the new work, which was regularly shown at fairs and was already establishing its presence on the commercial side of the art world.

What was remarkable about the show was not so much the selection of works, or the individual contributions of the philosophers at the conference, who mostly struggled to find a relation to the context of the exhibition. Most remarkable was the mere fact that the exhibition was the first attempt on an institutional level to connect post-internet art with the broader theoretical framework of speculative realism as such.

Of course, at that early point, very few pieces of post-internet art would have been dumped in the darkness of storage facilities. However, freeportism as a style does not only affect art that actually enters the storage facilities, but also work that strives to do so. Post-internet art’s marriage with philosophy was perhaps not straightforwardly meant to increase the former’s freeport eligibility, but in the end it did so, whether deliberately or not.

Philosophical Hedging

In trading, to hedge a position means to secure against future losses—like buying insurance against falling prices. Whenever a professional trader enters a speculative trade, she tries to mitigate the risks involved. Usually, this can be achieved in two ways. The first method is diversification, or bundling multiple positions whose risks neutralize each other. Venture capitalists routinely follow this recipe. Contemporary venture collectors mimic the same strategy. They buy the works of not only one young artist but of many. This helps to diversify the risk. Taste, subjective judgment, and emotional affinity give way to more risk-averse strategies of art portfolio management.

The second strategy is hedging. In the market this usually involves buying derivatives like forward contracts, options, swaps, and futures that help to lock in a future price. A small expenditure now can serve to guarantee returns later. Similar derivatives for artworks do not exist. But there are discursive constructions that serve the same purpose. Attaching philosophy to art is like buying a derivative.

How does philosophy work as hedging?

Creating an awareness of time and history requires intellectual and institutional efforts. The big time machines of the art world used to be museums. Starting in the late eighteenth century, they established an order of historical time, following the new scientific models of art historian and archaeologist Johann Joachim Winckelmann, as applied by Christian von Mechel and Dominique Vivant Denon.1

Today’s museums have a different focus. A national cultural identity and the maintenance of a historical heritage have been reduced to secondary goals. A lot of money is spent erecting new palaces of the arts. They look great. As architectural landmarks they serve all kinds of purposes, from tourist attractions to soft factors in competitiveness among cities and nations. But for the arts and for the construction of history and time, they don’t work as they used to. Instead of amassing a big collection, these institutions devote their resources to organizing temporary shows. A cultural canon is no longer their main concern.

The absence of history becomes most visible in their focus on the “contemporary.” Caught in the ever-changing presence of the now, museums have lost their function of developing a historical reserve. Throughout the museum’s history, art markets have profited from its canon-building efforts. As the buyers and lenders of last resort, museums have acted like the central banks of the art market. Grounded in a stabilized history and a canon, they have provided safety—in other words, the basis for nearly risk-free investment. Curators don’t do this. Biennials don’t do this. And museums no longer do this either. Today’s new repositories of art—freeports—operate entirely according to the laws of the market, and are therefore exposed to its fluctuations.

Here is where philosophy enters the picture. The traditional rhetoric of philosophy invokes an appeal to authority. A proper and well-grounded philosophy paper derives its status from calling on authors from the rich 2,500-year history of written thinking. It is exactly this historical reach that renders philosophers so valuable to contemporary art discourse. The more art texts are decorated with quotes and references to this long history of thought, the better they serve the purpose of guaranteeing the durability of the artworks associated with them.

The one and only requirement for hedge-worthy philosophy is therefore a formal one. Like ghosts from the past, this philosophy needs to call in the old authorities, by citing them or referencing their theoretical concepts. The more ancient, the more solemn, the better.

By this metric, speculative realism scores pretty high. In contrast to the French post-structuralism that preceded it, speculative realism began by dusting off the eternal, core questions of philosophy. Its main points of reference are scattered throughout the long history of the discipline. For the purpose of philosophical hedging it does not matter whether you argue for or against Kant. It is the name “Kant” that matters.

Another property of speculative realism adds to its hedging capabilities: it is completely devoid of a political agenda, unlike continental philosophy. For the sake of the purity of philosophical reasoning, most proponents of speculative realism steer clear of crude issues like political and economic theory, let alone political activism. For this reason, the risk of critical disruption or an unfavorable discursive intervention is very low. And when it comes to hedging, avoiding risk is what matters.

Speculative realism has no direct interest in the arts. Few of its thinkers ever touch art as a subject. Only rudimentary traces of aesthetics can be found. Recently, however, after the art world became interested in speculative realism, some of its thinkers felt inclined to utter statements regarding artistic practices—not so much to serve the interests of artists, but to cover the full spectrum of philosophy. This has introduced a measure of risk into philosophers’ involvement in the art world, albeit only a small one. Idiosyncratic aesthetic judgments by speculative realists have the potential to complicate their participation in the art world.2

A successful philosophical hedging requires a historically well-grounded theory that is connected via ample quotes and references to a long history of thinking, and that is wise enough to avoid adverse political and aesthetic judgments. In its approach to reactivating the classic question of philosophy and their main thinkers, speculative realism fulfills this purpose perfectly.

Rhetorical Appropriation

We should keep in mind that the artistic appropriation of philosophy does not entail an extensive discussion or rigorous critique of its theories and conclusions. That part is left to academic discourse. Artistic practices apply, transform, mirror, echo—and occasionally also precede—the findings of philosophers. One can of course criticize this appropriation as merely acting on the level of buzzwords. But the opposite suspicion can also be raised: perhaps the philosophical statements in question were written exactly for that purpose.

Apart from formal requirements and rhetoric relations, there are also more substantial ways in which speculative realism encourages and justifies an artistic production fit for freeports. These include its preoccupation with materialism, its object-oriented ontology, and its “anti-correlationist” stance. Before delving into these three subjects, however, I will pause to note that among the key terms that tie speculative realism to post-internet art, “speculative” and “realism” are not among them. This is because philosophy and art use these terms in significantly different ways. Philosophical speculation operates in a different domain than speculation in art markets. While the latter—related as it is to future prices, payments, and risk—concerns the domain of time, speculation in a philosophical sense usually concerns the domain of existence and abstraction. Speculation—at least in speculative realism—refers to a claim on the eternal existence of something otherwise inaccessible or not demonstrable.

There is a similar divergence in meaning when it comes to the term “realism.” Suhail Malik is an art theorist teaching at Goldsmiths and one of the main proponents of the idea that speculative realism has strong implications for contemporary art production. Malik points out that the philosophical term “realism” does not have much affinity with the “realism” known from art history: “Such a realism here is not to be confused with realism as a style or genre of art committed to ‘accurate’ representations of pre-existing reality, such a genre already assuming representation as an interval from a real elsewhere.”3

Materialism

The return of materialism in philosophical debates coincides nicely with a focus on materiality within the arts. The topic has been deemed so important that the magazine October dedicated a recent issue to materiality. The issue includes a questionnaire with responses from art theorists, art historians, and artists, who were asked to “think the reality of objects beyond human meanings and uses. This other reality is often rooted in ‘thingness’ or an animate materiality.”4

Contemporary materialism refers to the thread leading from Spinoza through Bergson to Deleuze and the Marxist tradition.5 Referring back to the Spinozian notion of the “conatus,” things are thought to be equipped with an agency of their own. A vitalist drive reigns over the material world. “One moral of the story is that we are also nonhuman and that things, too, are vital players in the world.”6

If material carries its own energy, there is less need for a discursive layer of communication. This approach has major consequences for art production. Materiality can speak for itself. When it comes to post-internet art, this is one of the strongest arguments for leaving aside the early attachment to social media platforms, and to online communication in general. The trust in the vibrant energy of matter helps to promote the retreat to traditional material production.

The consequences of this ideology for the art world become even clearer when compared to the aesthetic relations attached to preceding philosophical approaches: “This position sharply contrasts with the philosophical and cultural view dominant over the last half century, a view that affirms the indispensability of interpretation, discourse, textuality, signification, ideology, and power.”7 Once the layer of communication is thrown overboard, we are left with merely material things, and we have to assume that they can stand for themselves, regardless of what happens to them.

Object Orientation

The concept of the “object,” as it figures most prominently in Graham Harman’s “object-oriented ontology,” has little in common with vitalist materialism. Harman’s objects are paradoxical beings: “By ‘objects’ I mean unified realities—physical or otherwise—that cannot fully be reduced either downwards to their pieces or upwards to their effects.”8 The only common trait is the assumption of a reality that both material things and Harman’s objects belong to. Navigating the philosophical quagmire of the old discipline of epistemology, Harman postulates the object as a being, not necessarily material, that is neither explainable from its components nor from its relations. If we regard the artwork as an object, Harman’s theory offers a justification for a belief in the autonomous, inherent reality of the artwork. Its unique quality can neither be fully explained by the process of production, nor can it rely on its relation to the beholder: “At issue is the independence of artworks not only from their social and political surroundings, their physical settings or their commercial exchange value, but from any other object whatsoever.”9 In addition, the object takes the place formerly occupied by the genius—an individual possessed by an inherent talent or ability that is not subject to educational efforts but naturally inborn, and for this reason someone who is self-reliant and free of outward relations.

Harman’s metaphysical conception of objecthood bears a striking resemblance to the requirements for things to be stored in a freeport. Whether intentional or not, his description of objects perfectly fits the artistic practices of freeportism: “The only way to do justice to objects is to consider that their reality is free of all relation, deeper than all reciprocity. The object is a dark crystal veiled in a private vacuum: irreducible to its own pieces, and equally irreducible to its outward relations with other things.”10 On other occasions he speaks of objects being “vacuum-sealed.”11 With well-packaged artworks coming so close to Harman’s idea of the object, the freeport represents the ideal environment for object-oriented works of art.

Anti-Correlationism

In After Finitude, Quentin Meillassoux writes: “By ‘correlation’ we mean the idea according to which we only ever have access to the correlation between thinking and being, and never to either term considered apart from the other.”12 For our purposes we do not need to follow all of Meillassoux’s intricate lines of argumentation as he defends his refutation of correlationism against basically all the major representatives of modern philosophy, from Kant—whom he deems his main opponent—onward. The consequences for the arts of the anti-correlationist approach are easy to draw out.

According to Suhail Malik, “that a reality such as art can only be apprehended by the thinking or consciousness of it and that it is necessarily accompanied by that thinking and consciousness is the dependency that Quentin Meillassoux has influentially called correlationism.”13

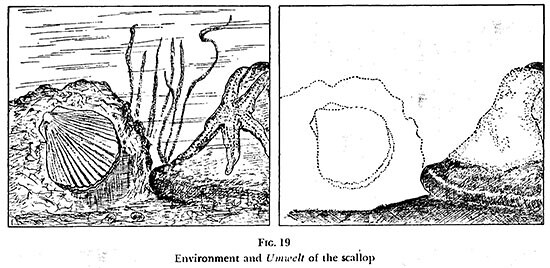

Anti-correlationism, then, frees art from aesthetic considerations and the involvement of a beholder. Under these ideological premises the existence of an artwork requires neither human perception nor consciousness. Very much like the “arche-fossil” that Meillassoux constructs as a hypothetical 4.65-billion-year-old object, the artwork may live for an indefinite amount of time in eternal darkness without losing its real existence. Malik has drawn further and more far-reaching conclusions from Meillassoux’s assumptions, translating them into requirements for anti-correlationist works of art: “The demand here upon contemporary art is strictly non-trivial: it removes subjective interpretation or experience as a condition or telos of the artwork, and therewith collapses the entire edifice of the contemporary art paradigm.”14

Stripped of interpretation and experience, the purpose of exhibiting artworks becomes completely empty. Consequentially, artworks no longer need to be shown anywhere: “An art responsive to this theoretically-led imperative would be indifferent to the experience of it, an art that does not presume or return to aesthetics, however minimal or fecund such an aesthetics might be.”15 There can be no better justification for an artistic production that goes straight from the artist’s studio to the storage facility, without ever being publicly displayed or shown to anybody.

Conclusion

Speculative realism, with its emphasis on material and objects and its repudiation of the beholder, provides an almost perfect ideology for an artistic production catering to freeports as sites of material storage and non-exhibition.

This contradicts Suhail Malik’s claim that speculative realism opens the way for an entirely different contemporary art. He writes: “From yet another angle, realism’s provocation to art is the undoing of aesthetic experience as a condition or term of art, even in the avowal of art’s ineluctable materiality. Which is to say that realism speculatively indicates the conditions for another art than contemporary art.”16 On the contrary, considering the practice of post-internet art, the theoretical framework of speculative realism does precisely the opposite of what Malik claims it does. It offers an ideological framework for today’s dominant art practice and is uniquely adapted to the current state of markets and financial feudalism, satisfying a demand for speculative assets hidden in the treasure chambers of freeports.

See Stefan Heidenreich, “Make Time: Temporalities and Contemporary Art,” Manifesta Journal 9 (September 2009): 69–79.

Cf. Graham Harman, “Art Without Relations,” ArtReview, September 2014: “As for the dead, I will take an even bigger risk, and suggest that we give a second look to none other than the Dutchman M.C. Escher—the favourite artist of countless children and few respectable adults—for reasons similar to those given in Bruskin’s case. If nothing else, a counterfactual art history in which Escher looms large is a delightful thought experiment” →.

Suhail Malik, “Reason to Destroy Contemporary Art: 21st Century Theory,” Spike Art 37 (Autumn 2013) →.

David Joselit, C. Lambert-Beatty, and Hal Foster, “A Questionnaire on Materialisms,” October, Winter 2016: 3.

See Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (Durham: Duke University Press 2010), xiii.

Ibid., 4.

Realism Materialism Art, eds. Christoph Cox, Jenny Jaskey, and Suhail Malik (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2015), 15.

Harman, “Art Without Relations.”

Ibid.

Graham Harman, The Quadruple Object, (Alresford: John Hunt, 2011), 47.

Graham Harman, Tool Being. Heidegger and the Metaphysics of Objects (Chicago: Open Court, 2002), 283.

Quentin Meillassoux, After Finitude. An Essay on the Necessity of Contingency (London: Continuum 2008), 5.

Malik, “Reason to Destroy Contemporary Art”

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.