Why return to the history of connoisseurship, and why now? Its particular virtues—deep looking, an eye for subtle markers of historical merit, and an obsession with the “hand of the master”—seem rooted firmly in the past at a time when art is ever more obsessed with the present. An essay on “Marxism and Connoisseurship” today is likely to seem both ridiculous and dubious, like proposing a political recuperation of dressage. Yet I think that theorizing where we stand in relationship to the concept can save a lot of confusion, and clarify the stakes of cultural critique.

“No moment of the discipline’s history has been more reviled,” one recent scholarly article puts it. “Connoisseurship has become a byword for snobbery, greed, and professional mystification.”1 Last year, speaking at a conference on “The Educated Eye,” one British Museum curator put the matter even more aggressively: “[I would] rather gouge my eyes out with a rusty penknife than describe myself as a connoisseur.”2

And yet, a twist: while art flees from its historical association with connoisseurship, the very same virtues are undergoing a boom in the culture beyond the gallery and the museum. Everywhere consumers are being encouraged to interpolate themselves as connoisseurs. Indeed, the recent past has conjured up entire new fields of connoisseurship, as if by magic.

One hundred years ago, when the classic connoisseurs of art like Bernard Berenson and Max Friedlander were at the height of their prestige, Henry Ford had only just gotten his assembly line rolling, the great symbol of capitalist commodity production. Today, interest in collectible cars among moneyed Baby Boomers far outpaces investment in traditional status symbols like art or wines.3 Symposia with titles like “Connoisseurship and the Collectible Car” promise the knowledge necessary to navigate this new terrain.

An obsession with refined consumption permeates contemporary culture, sometimes to the point of unintentional comedy. Consider Martin Riese, Los Angeles’s famed “water sommelier,” who promises to teach how to identify both region and depth from which bottled water comes. Riese promises that his water tastings will expand your palette, unlocking new realms of gustatory sensitivity.4

Such hipster connoisseurship is vulnerable to being accused of exactly the same associations with “snobbery, greed, and professional mystification” as old-school connoisseurship. When Brooklyn chocolatiers the Mast Brothers—who offer a Red Hook tasting room to learn the subtleties of their bean-to-bar concoctions—were accused of “remelting” common chocolate, the resulting wave of schadenfreude made the New York Times.5

Meanwhile, confusingly, while fine art has labored mightily to distance itself from the elitist connotations of connoisseurship, no one seems to much like what the post-connoisseurial museum is shaping up to be, from popular critics of art to academics. Holland Cotter laments that the crowds attracted to spectacular contemporary art mask the withering audience for anything that is not of-the-now.6 Hal Foster attacks contemporary museums for becoming little more than props for callow “cultural tourism” and caving in to “a mega-programme so obvious that it goes unstated: entertainment.”7

Rain Room, made by the London-based design group Random International and wholly owned by high-end home décor makers Restoration Hardware, has attracted massive crowds and long lines wherever it has toured to a museum. It consists of a walk-in environment where, through the magic of motion sensors and ingenious plumbing, you can experience the thrill of walking through a torrential rainstorm without getting wet. The piece is a lot of fun and great for selfies.8 Whether such qualities require the concepts of “art” or “artists” as a vehicle—and therefore whether museums might be talking themselves out of a job by promoting it—remains an open question.

Indeed, last Christmas, the Glade® scented candle company brought a pop-up installation called The Museum of Feelings to Lower Manhattan.9 The environment ripped off elements of Yayoi Kusama’s mirrored rooms and James Turrell’s perception-bending light installations, adding in a bunch of interactive wizardry and customizable “selfie stations” to share one’s mood. It was met with exactly the same kind of blockbuster lines as Rain Room encountered at MoMA and LACMA, with waits stretching to hours. The fact that this “museum” experience was authored by a faceless marketing company called Radical Media rather than named artists made no difference.

Art and craft, art and entertainment, art and design have long circled each other in wary fascination and antagonism. The present scene reduces this venerable drama to one of those stage farces of mutual misidentification, where one character is always storming off to confront her enemy just as that foe leaps onstage through the other door.

Art and Industry

The rejection of “connoisseurship” in today’s aesthetic discourse may be seen simply as the pragmatic outcome of a much-changed contemporary art system. Eclecticism and pluralism are the chief features of the post-1960s art scene; the notion, associated with connoisseurship, of establishing a single firm set of rules for evaluation seems dated at best. Yet the airy avowal that “anything can be art” masks the deeper, unexamined ways that assumptions formed in Europe’s recent past still structure how art is viewed and valued even within the polyglot international art world.

Among art historians, it is a commonplace that the idea of “Fine Art” is a relatively recent construction. Its roots lie in the humanism of the Renaissance and the rationalism of the Enlightenment. It was given further impetus by the formalization of Galilean science, which shook up old tables of knowledge. As Larry Shiner writes:

By joining the experimental and mathematical methods, seventeenth-century scientists not only laid the basis for the sciences to achieve an autonomous identity but also drove a wedge into the liberal arts, pushing geometry and astronomy towards disciplines like mechanics and physiology that seemed more appropriate company than music, which was itself moving towards rhetoric and poetry.10

As for painting and sculpture, they could not have existed as “autonomous” art objects before the birth of the modern museum, which gave the necessary institutional context to view art objects outside of decoration and patronage.11 The founding of the Musée du Louvre in 1792 was one of the more unexpected byproducts of the French Revolution.

Yet the truly modern form of capital-A Art is a creation of the Romantic period in Europe (roughly 1800–1850), which birthed the ideal of the artist as autonomous visionary. This cult of art emerged opposite the intensifying upheaval of the Industrial Revolution: small workshop production and small farms were being replaced by increasingly industrialized, urban forms of production and consumption; laborers became anonymous and no longer had creative input into their work; consumers knew less and less about where or by whom goods had been produced.

Shiner again:

Whereas the eighteenth century split the older idea of art into fine art versus craft, the nineteenth century transformed fine art itself into a reified “Art,” an independent and privileged realm of spirit, truth, and creativity. Similarly, the concept of the artist, which had been definitively separated from that of the artisan in the eighteenth century, was now sanctified as one of humanity’s highest spiritual callings. The status and image of the artisan, by contrast, continued to decline, as many small workshops were forced out of business by industrialization and many skilled craftspeople entered the factories as operatives performing prescribed routines.12

In Europe, the most influential writers to give voice to the age’s intensified artistic sensibility were Charles Baudelaire (1821–1867) in France, and John Ruskin (1819–1900) in England. These men would have been in the same high school class with Karl Marx (1818–1883) and Friedrich Engels (1820–1895), the theorists of the new working class, which is no coincidence. “There is no understanding the arts in the later nineteenth century,” writes the Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm, “without a sense of this social demand that they should act as all-purpose suppliers of spiritual contents to the most materialist of civilizations.”13

This story of art, clearly, is Eurocentric. The operation by which cultural objects from non-European cultures were “reimagined as ‘art’ in the modern sense of a product of individual expression meant for individual secular contemplation” has been extensively studied.14 Such “autonomous” values have sometimes been imposed from without by the most sordid of imperialisms. Yet in another respect, they might also be viewed as part of the internal psychic economy of capitalism, a tendency active wherever its values are adopted.

For example, following the Meiji Restoration of 1868, a formerly cloistered Japan decided to industrialize on its own terms in reaction to the expansion of the empires of Europe and the United States. Art historian Dōshin Satō shows in Modern Japanese Art and the Meiji State that the Japanese equivalent term for “fine art,” bijutsu, is a product of exactly this period of social transformation.15 The prestige of bijutsu, Satō argues, was constructed in opposition to another new-born term, kaigo, approximating the idea of “craft,” which became associated with industrial products made for export.16

An intensifying self-consciousness about fine art is a dialectical counterformation to the intensifying social weight of capitalist industry. They are twinned developments, and are thereby implicated in a whole web of class tensions. Art-consciousness is, in this respect, as distinct a symptom of capitalism as wage labor or the commodity form itself.

Destructive Criticism

The modern connoisseur is also a historical product, born from the same intellectual ferment that produced the modern artist. Indeed, the two fields are entwined; the formalization of the ideals of connoisseurship legitimated art as a prestige object of study.17] infinitely more estimable, were one assur’d it was the picture of the learned Count of Mirandula, Politian, Quicciardini, Machiavel, Petrarch, Ariosto or Tasso; some famous Pope, Prince, Poet, Historian or Hero of those times.” Quoted in Brian Cowan, “A Open Elite: The Peculiarities of Connoisseurship in Early Modern England,” Modern Intellectual History, Vol. 1, No. 2 (August 2004), 160.]

The same nineteenth century that gave rise to the cult of the autonomous artist witnessed, within theories of connoisseurship, a parallel development: an increasingly monomaniacal focus on questions of authorship. In Europe, the key figure is the Italian physician, statesman, and theorist Giovanni Morelli (1816–1891)—like Baudelaire and Ruskin, the near-exact contemporary of Marx and Engels.

For earlier proponents of “scientific connoisseurship” such as the Englishman Jonathan Richardson (1667–1745), attribution was one task among others for the connoisseur.18 For Morelli, attribution became the main obsession—to the point of paradox.

All that was most obvious in a painting was liable to be copied by lesser hands. The true personality of the artist, therefore, would reveal itself in overlooked, almost unconscious details, such as the uniquely characteristic way that a hand or an earlobe was rendered.19 True art appreciation could only mean looking past the “general impression” and seeking out these minute traces of creative individuality.

Because of Morelli’s spectacular success in using this aesthetic forensics to reattribute famous paintings, he gained great renown in the late nineteenth century. Yet, despite the seemingly technical nature of his endeavor, it is worth emphasizing the degree to which Morelli’s obsession with authorship constituted not just a method of attribution but a particularly modern form of taste.

In his treatise Italian Painters, Morelli’s “Principles and Method” are outlined in the form of an ingenious parable: an imagined encounter between a Russian visitor to Florence and a wise older Italian connoisseur. After hearing the Italian hold forth on authentication issues, the Russian departs, thinking him “dry, uninteresting, and even pedantic,” and concluding that his theories “might even be of service to dealers and experts, but in the end must prove detrimental to the truer and more elevated conception of art.”20

Returning to Russia, however, the narrator finds himself haunted by the encounter. He attends a showcase of a prince’s Italian pictures before they are sold off at auction. “I could hardly believe my eyes, and felt as if scales had suddenly fallen from them,” our narrator tells the reader. “In short, these pictures, which only a few years before had appeared to me admirable works by Raphael himself, did not satisfy me now, and on closer inspection I felt convinced that these much-vaunted productions were nothing but copies, or perhaps even counterfeits.”21

Morelli suggests the term “destructive criticism” for his method.22 The superficial appreciation of art is destroyed; in its place, a new, ultra-refined appreciation is recovered at a higher level.

Undergirding this aesthetics is a subtle politics of looking.23 On the one hand, the traditional elitism of connoisseurship is on full view in Morelli’s text, with his proxy stating that “the full enjoyment of art is reserved only for a select few, and that the many cannot be expected to enter into all the subtleties.”24

At the same time, this aristocratic temperament is not just rooted in the past, but represents a reaction to a quite modern phenomenon: the incipient commercialization of culture. Indeed, the evils Morelli associates with the “general impression” have a particular embodied metaphor, one that will be familiar within contemporary debates about the transformation of museum culture: the tourist.

“The modern tourist’s first object is to arrive at a certain point; once there, he disposes of the allotted sights as quickly as possible, and hurries on resignedly to fresh fields, where the same programme is repeated,” remarks Morelli’s Italian connoisseur, almost as his opening statement. “In the way we live nowadays, a man has scarcely time to collect his thoughts. The events of each day glide past like dissolving views, effacing one another in turn. There is thus a total absence of repose, without which enjoyment of art is an impossibility.”25

Consequently, the “destructive” aspects of Morelli’s criticism can be read as a defensive operation, as old rhythms of culture were being subordinated to the demands of modern commerce.26 If the cult of art was constructed as a reaction to the intensifying social weight of capitalist commodity production, the archetype of the connoisseur of images was constructed as the counterpoint to the mere consumer of images.

The Connoisseur’s Paradox

The intellectual implications of such “scientific connoisseurship” become clearer still if we look to Morelli’s most celebrated follower, Bernard Berenson (1865–1959), who formalized the “Morellian Method” into an alibi for the art market of the Gilded Age.

Berenson systematized Morelli’s approach, and further established a new idea of recognizing “artistic personality” as the highest aim of aesthetic intelligence. “The complete description of an artistic personality amounts to identifying an artist’s characteristic habits of execution and visualization, noting their changes, deducing from them the ways in which other masters influenced this artist, and finally commenting upon his qualities of mind and temperament, as evidenced by his paintings,” explains Carol Gibson-Wood.27

It can be argued, based on this, that the particular, near-religious charge of this strain of art connoisseurship is owed to the fact that it seems to offer access to all those qualities lost in the transition to alienated consumption: a sense of the specific conditions of production, the aura of the humanity behind the object.

Yet in reviewing Berenson’s methodological treatise, Rudiments of Connoisseurship (1898), what also becomes clear is just how oddly the nineteenth-/early-twentieth-century obsession with authorship fit its particular privileged object. Renaissance painting had been rooted in the transition from Europe’s medieval world with its workshops and guilds, well before the actuation of Romanticism’s ideal of the autonomous artist.28] created an artist who was more consistent, more distinctive, and more readily recognizable than any actual artist.” S. N. Behrman, Duveen: The Story of the Most Spectacular Art Dealer of All Time (New York: Little Bookroom, 2003), 107.] Indeed, this particular mismatch explains connoisseurship’s micrological obsessions in the first place.

“The artist often left most of the work, if not the whole, to be executed by assistants, unless a special agreement was made that it was entirely or in its most important features, to be from his own hand, although even then he did not always adhere to the terms of his contract,” cautions Berenson, explaining to the reader the difficulty of arriving at true knowledge of authorship. Referring to a Raphael that had been downgraded to “Workshop of Raphael”: “Often there could have been no pretense at execution on the great master’s part. Everything painted in his shop was regarded as his work, even when wholly executed, and even when designed by his assistants.”29

At this juncture, the projective character of Berenson’s hunt for the signs of “artistic personality” within and between works may recall what Michel Foucault says about the operation of the “author function” in literature. In his well-known 1969 lecture “What Is An Author?” Foucault argued that authorship was not a given but merely one historical mode of reception:

Such a name permits one to group together a certain number of texts, define them, differentiate them from and contrast them to others. In addition, it establishes a relationship among the texts … The author’s name serves to characterize a certain mode of being of discourse: the fact that the discourse has an author’s name, that one can say “this was written by so-and-so” or “so-and-so is its author,” shows that this discourse is not ordinary everyday speech that merely comes and goes, not something that is immediately consumable. On the contrary, it is a speech that must be received in a certain mode and that, in a given culture, must receive a certain status.30

Foucault’s interest in the author function remains principally epistemological. Yet even in this passage, the French philosopher hints at how it fulfills an aesthetic function: it serves to differentiate its objects from the “immediately consumable,” granting them a “certain status,” and setting them off from the oblivion of “everyday,” anonymous production. The form of artistic consciousness propounded by Morelli and Berenson might, finally, be thought of as the delectation of the author function.

The Ready-Made Eye

If there is one artwork of the twentieth century that would make, in retrospect, the connoisseur’s obsession with the “hand of the master” appear antique, it is Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain of 1917 (the same year that Berenson’s Study and Criticism of Italian Art appeared in the United States). The lasting provocation of this appropriated urinal, presented as sculpture, stands at the foundation of contemporary art’s post-medium pluralism.31

Yet it is a much-remarked-upon irony that the original Fountain, which was lost, was replicated in 1950 and 1963 with Duchamp’s supervision of all the details. This quintessential celebration of the industrial object became, essentially, a precious trophy carefully constructed to evidence, if not the “hand of the master,” then definitely his signature.32

The Fordist assembly line had only kicked off in 1913, the same year Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase appeared in New York. An industrial and consumerist world would make new kinds of objects available for repurposing as artistic expression, via collage or mining the pathos of the found object. Such emergent strategies would throw into question many assumptions about what fine art looked like.

Yet, in some ways, rather than representing a break, the changes Fountain signaled actually consummated the internal logic already put in play by “scientific connoisseurship.” Duchamp famously professed himself indifferent to “retinal art”; Morelli’s “destructive criticism” opposed itself to “superficial impression,” and had already turned art appreciation into a cerebral guessing game, centered on questions of authorship.33

In its day, Duchamp’s Fountain remained a novelty, if not an outrage. Its influence would not be truly ascendant until the 1960s, when rising Pop and Conceptual artists discovered in the “ready-made” a legitimating tradition. And it is yet another historical irony that, just as industrial materials were entering into the mainstream of fine art, the conventions of fine art were accumulating around the quintessential industrialized art: Hollywood film.34 Directed at a mass audience and subject to Taylorized production procedures, individual authorship was so little important to Hollywood’s Golden Age (roughly the Twenties to the Forties) that the term “the genius of the System” has come into currency to indicate how the corporation itself, the Studio, fulfilled the role of artist.35

Yet by the 1960s, film would become recuperated under “auteur theory” in the writings of figures like André Bazin, establishing the medium as an object for serious intellectual attention rather than a disposable novelty. Critic-turned-filmmaker François Truffaut’s book of interviews with Alfred Hitchcock reoriented public perception of the British director, from a flashy hired gun to an artist whose oeuvre displayed a unified personal vision.

“Over a group of films, a director must exhibit certain recurrent characteristics of style, which serve as his signature,” another proponent of “auteur” theory, Andrew Sarris, would write in 1962, sounding for all the world like Berenson holding forth on “artistic personality” in painting. “The way a film looks and moves should have some relationship to the way a director thinks and feels.”36 The same conceptual apparatus that could reach back in time to transform Raphael within his Renaissance workshop into an autonomous visionary could transform Hitchcock, working for Paramount, into his distant cousin.37

No Quarter

In the final paragraphs of “What Is An Author?,” Foucault offers what amounts to a literary prophecy. Associating the author function with “our era of industrial and bourgeois society, of individualism and private property,” he hypothesizes that “as our society changes, at the very moment when it is in the process of changing, the author function will disappear.”38

What is puzzling is that, outside the boutique world of the fine arts and the academy, plenty of texts already fulfilled this post-authorial condition—indeed, the ones that most natively reflected the ideology of “industrial and bourgeois society.”

“The words which dominated Western consumer societies were no longer the words of holy books, let alone of secular writers, but the brand-names of goods of whatever else could be bought,” wrote Eric Hobsbawm of the cultural transformations of 1960s and after. The same could be said of the world of images, of which museum-and-gallery art, with its byzantine intellectual concerns, could only form a subordinate part.39

On balance, locating “bourgeois” values with either authored or un-authored work is futile. Both tendencies are located within capital, which on the one hand transforms everything into equally exchangeable units, but on the other, reintroduces distinction in the hunt for the kinds of “monopoly rents” that only unique status symbols can provide. As David Harvey has written, this restless dynamic of capital “leads to the valuation of uniqueness, authenticity, particularity, originality, and all manner of other dimensions to social life that are inconsistent with the homogeneity presupposed by commodity production.”40

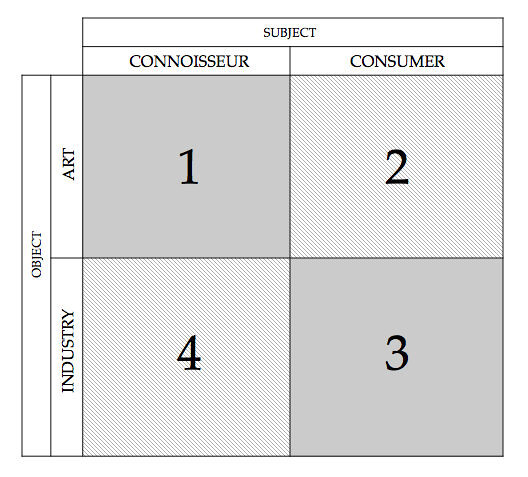

If connoisseurship seems to have an unsettled status within contemporary culture, it is because it is caught in these crosswinds. Since production and reception assume one another but are distinct, we can create a matrix of the possible intersection of our terms:

Quadrant 1 represents the situation in which aesthetic objects designed to be read according to the conventions of fine art meet an audience primed to receive them, the best image being the connoisseur happily nested in the museum.

Quadrant 2 represents these same types of fine art objects read in a non-connoisseurial way. The figure would be the tourists flowing through the Uffizi in Morelli’s nightmares, or present-day multitudes lining up to snap a picture of the Mona Lisa in the Louvre because of its media-icon status.

Quadrant 3 takes us into the world of industrially produced culture, as it meets its target consumer. For the moviegoer looking for an air-conditioned break with a Hollywood thriller, no less than the car buyer looking to balance sexy design with gas mileage, what the object says about its maker or how it fits into a larger creative vision is not generally the most important factor at play.

Quadrant 4, at last, stands for the situation in which the objects of the “culture industry” are recuperated by connoisseurship: Hollywood film sublimated via auteur theory, automobiles transfigured via new-minted cultures of classic-car appreciation. “The car is always an assemblage,” advised one sage recently, “not just an object, but a bundle of stories, paperwork, contexts, as well as parts.”41

The argument in this essay has been that the divisions that form this matrix reflect the way that culture refracts the alienation and class stratification characteristic of capitalist society. Given these roots in political economy, it should be no surprise that at different times and places, pressing the merits of any of these four quadrants over the others has taken the appearance of political critique.

Thus, in what can only be described as a kind of Marxist connoisseurship, the art object and the free play of aesthetic perception have often been seen as standing positively for a glimpse of the unalienated world that could be, beyond capitalism (Quadrant 1). At other moments, unmasking the fine art cult as the product of class privilege has been the key vector of critique (Quadrant 2).

In the early twentieth century, subordinating the individual, bourgeois values of art to industry with the idea of producing “art for all” rather than luxury goods for an elite took on a socialist cast in Soviet Productivism and in the Bauhaus (Quadrant 3). At other times, recovering the humanity and individual creativity occluded behind the commodity might well have its own polemical charge (Quadrant 4).42

Referring to the poles of fine and mass art, Theodor Adorno once wrote, “Both bear the elements of capitalism, both bear the elements of change … both are the torn halves of an integral freedom, to which however they do not add up.”43 To elaborate him, you could say that all four quadrants of this matrix are torn parts of an integral freedom, to which they, nevertheless, do not add up.

What seems to me to be characteristic of the present moment is the intensification of the confusion between the different positions. A rapacious contemporary capitalism relentlessly seeks to carve out spaces of nouveau-snobbery and privilege, while also despoiling and profaning old spaces of solace—sometimes simultaneously. But this chaotic situation might have a use, at least as an illustration.

One of the operations of power is to deflect the critique of capitalism onto the terrain of a more limited cultural critique. The condemnation of arrogant elitism or dumbed-down consumerism, of the detached art object or the degraded commodity form, has value. But, being partial, such critiques are always liable to overshoot their mark, and become their opposite. In the end, you have to keep your sights on transforming the system that produced such contradictions in the first place.

Jeremy Melius, “Connoisseurship, Painting, and Personhood,” Art History, April 2011, 289.

Allan Wallach, Bully Pulpit, Panorama, Fall 2015 →

“Classic cars are gaining attention due to their nearly 500 percent returns over the past decade, outpacing art and wine by more than 100 percent, as reported by the Knight Frank Luxury Investment Index.” Deborah Nason, “‘Passion investing’ in classic cars is gaining speed,” CNBC, January 4, 2016 →

Martin Riese, “How America’s Only Water Sommelier Is Changing the Way People Taste H20,” Eater, April 7, 2015 →

Sarah Maslin Nur, “Unwrapping the Mythos of Mast Brothers Chocolate in Brooklyn,” New York Times, December 20, 2015 →

Holland Cotter, “Toward a Museum of the 21st Century,” New York Times, October 28, 2015 →

Hal Foster, “After the White Cube,” London Review of Books, March 19, 2015 →

Carolina Miranda argues that it is, in fact, designed to be experienced photographically, remarking that Rain Room is “more of a one-sided Hollywood set ideal for picture-making than a full-fledged environmental installation that will subsume you with its awesome water power.” Carolina A. Miranda, “Art for Instagram: 3 lessons from LACMA’s ‘Rain Room,’” Los Angeles Times, December 2, 2015 →

See Ben Davis, “Scented Candle Installation Brings Optimistic Mood to Lower Manhattan,” artnet News, December 16, 2015 →

Larry Shiner, The Invention of Art: A Cultural History (Chicago: University of Chicago, 2003), 70.

Ibid., 180.

Ibid., 187.

Eric Hobsbawm, The Age of Capital: 1848–1875 (New York: Vintage: 1996), 335.

Elaine O’Brien, “The Location of Modern Art,” Modern Art in Africa, Asia, and Latin America: An Introduction to Global Modernisms, eds. Elaine O’Brien, Everlyn Nicodemus, Melissa Chiu, Benjamin Genocchio, Mary K. Coffey, Roberto Tejada (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013), 5.

Dōshin Satō, Modern Japanese Art and the Meiji State: The Politics of Beauty (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2011).

The transformation of Japanese artist identity from “artisans with technical skills” to “full-fledged intellectuals who could express their individual impressions of the world” would develop fully only after the initial period of corporatism of Japan’s early industrial drive, and as a reaction to the latter. Gennifer Weisenfeld, “Western Style Painting in Japan: Mimesis, Individualism, and Japanese Nationhood,” Modern Art in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, 171.

Prior to Jonathan Richardson (1667–1745), the English cultural elite favored a “cabinet of curiosities” aesthetic, and had little value for art or the artist as particularly exalted. As late as 1689, one of the leading cultural figures of his day, John Evelyn (1620–1706), could write, “I am in perfect indignation of this folly as when I consider what extravagant summs … given for a dry scalp of some (forsooth) Italian painters hand let it be of Raphael or Titian himselfe, [which would be

For Richardson, attribution was slightly less important than the discernment of “Quality,” for which he had devised a humorously elaborate eighteen-point scale. See Carol Gibson-Wood, Studies in the Theory of Connoisseurship from Vasari to Morelli (New York: Garland Publishing, 1988), 103–107.

Carlo Ginzberg compares Morelli’s method to both Sherlock Holmes and Sigmund Freud, who, indeed, was influenced by Morelli. See “Clues: Roots of an Evidential Paradigm,” Clues, Myths, and the Historical Method, trans. John Tedeschi and Anne C. Tedeschi (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013), 96–125.

Giovanni Morelli, Italian Painters: Critical Studies of Their Works, trans. Constance Jocelyn Ffoulks (London: John Murray, 1900), 59 →

Ibid., 60.

Ibid., 59.

As to day-to-day politics, Morelli served in parliament and was a partisan of the Count of Cavour. He was a patriot who fought in the revolutions of 1848, but was a moderate monarchist rather than on the side of the radical left-wing elements of the Italian political scene. “Principles and Method” ends with an allusion to Morelli’s self-perception as fitting nowhere between two extremes: unable to find the Italian connoisseur, the Russian narrator finds that those who knew him offer contradictory accounts of his fate and political profile: One person remembers him as a “Codino,” or reactionary monarchist, while another describes him as having been an “anarchist.” Ibid., 61–62.

Ibid., 25.

Ibid., 9.

Morelli’s relationship to the art market was itself contradictory. On one hand, he acted as a broker for many famous Italian works of art, helping to shape, in particular, Britain’s National Gallery. On the other, a law protecting Italy’s artistic heritage from sale bears his name.

Gibson-Wood, 246.

Because the idea of the artist thus proposed represented a fictional unity, it was possible to conjure a coherent “artistic personality” where none existed. Such is the case with Berenson’s creation “Amico di Sandro,” his name for a previously unknown Renaissance artist that he deduced lay behind a sequence of works that were connected to, but did not fit the exact signatures, of any of an array of major figures. The intuition later proved to be false. “In Amico di Sandro he [Berenson

Bernard Berenson, Rudiments of Connoisseurship: Study and Criticism of Italian Arts (New York: Schocken Books, 1962), 114.

Michel Foucault, “What Is An Author?” in Aesthetics, Method, and Epistemology, ed. James D. Faubion (New York: New Press, 1999), 210–211.

It is amusing to note that a controversy hovers over the authorship of Fountain. In April 1917, Duchamp wrote a letter stating, “One of my female friends under a masculine pseudonym, Richard Mutt, sent in a porcelain urinal as a sculpture; it was not at all indecent—no reason for refusing it. The committee has decided to refuse to show this thing. I have handed in my resignation and it will be a bit of gossip of some value in New York.” That artist would likely have been Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, the proto-Dada, proto-performance artist, a known associate of Duchamp’s who had already been working in found-object art. Contemplating what the implications of such a monumental reattribution would be throws into relief the degree to which our understanding of this quintessentially anti-artisinal artwork rests on the classic obsession of connoisseurship: appreciation of the “artistic personality” behind the work. See Sophie Howarth, revised by Jennifer Mundy, “Marcel Duchamp: Fountain,” Tate website →

“Duchamp signed each of these replicas on the back of the left flange ‘Marcel Duchamp 1964’. There is also a copperplate on the base of each work etched with Duchamp’s signature, the dates of the original and the replica, the title, the edition number and the publisher’s name, ‘Galleria Schwarz, Milan’. For some, such replicas seemed to undermine cardinal qualities of ready-mades, namely, that they should be mass-produced items and ones chosen by an artist at a particular moment and time. Duchamp, however, was happy to remove the aura of uniqueness surrounding the original ready-mades, while the production of replicas ensured that more people would see the works and increased the likelihood that the ideas they represented would survive.” Ibid.

Indeed, in his 1960 denunciation of Morellian connoisseurship of painting, Edgar Wind describes its implications in terms that prophecy many a critique of the gamesmanship of Conceptual Art: “If we allow a diagnostic preoccupation to tinge the whole of our artistic sensibility, we may end by deploring any patient skill in painting as an encroachment of craftsmanship upon expression.” Edgar Wind, “Critique of Connoisseurship,” Art and Anarchy (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1985), 46.

Lawrence Levine traces how the “high culture” model of sacred solo author came to be transposed onto practices that would seem distant from them. “To say that sacralization remained an ideal only imperfectly realized is not to deny that it became a cultural force. As with many ideals, the contradictions were resolved not primarily by denying them but more powerfully by failing to recognize them. Thus the great Hollywood director Frank Capra, who was, as all directors are, dependent upon writers, cameramen, editors, and actors, could assert as his credo and the reality of his career: ‘One man, one film.’ Film directors who ignored, or downplayed, the collective nature of their art and conceived of themselves as auteurs, with the model of the novelist so clearly in mind, were not aberrations.” Lawrence W. Levine, Highbrow/Lowbrow: The Emergence of Cultural Hierarchy in America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1988), 168.

See Thomas Schatz, The Genius of the System: Hollywood Filmmaking in the Studio Era (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010)

Andrew Sarris, “Notes on the Auteur Theory in 1962,” in Film Culture Reader, ed. Adams P. Sitney (New York: Cooper Square Press, 2000), 132.

According to Hitchcock’s biographer, Truffaut’s book of interviews “hurt and disappointed just about everybody who had ever worked with Alfred Hitchcock, for the interviews reduced the writers, the designers, the photographers, the composers, and the actors to little other than elves in the master carpenter’s workshop.” Donald Spoto, The Dark Side Of Genius: The Life Of Alfred Hitchcock (Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 1999), 495.

Foucault, 222.

Hobsbawm continues: “The images that became the idols of such societies were those of mass entertainment and mass consumption: stars and cans. It is not surprising that in the 1950s, in the heartland of consumer democracy, the leading school of painters abdicated before image-makers so much more powerful than old-fashioned art.” Eric Hobsbawm, Age of Extremes: A History of the World, 1913–1991 (New York: Vintage Books, 1991), 513.

David Harvey, “The Art of Rent,” Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution (London, Verso, 2012), 109–110.

Michael Shanks, “car collection—connoisseurship and archaeology,” mshanks.com, March 8, 2015 →

Fascinatingly, Walter Benjamin, the theorist of the revolutionary potentials of “mechanical reproducibility,” also seems to give the best account of revolutionary connoisseurship: “The most profound enchantment of the collector is the locking of the individual items within a magic circle in which they are fixed as the final thrill, the thrill of acquisition, passes over them. Everything remembered and thought, everything conscious, becomes the pedestal, the frame, the base, the lock of his property. The period, the region, the craftsmanship, the former ownership—for a true collector the whole background of an item adds up to a magic encyclopedia whose quintessence is the fate of his object.” Walter Benjamin, “Unpacking my Library: A Talk about Book Collecting,” Illuminations, trans. Harry Zohn, ed. Hannah Arendt (New York: Schocken Books, 1969), 60.

Theodor Adorno, “Adorno to Benjamin,” Aesthetics and Politics (London: Verso, 2007), 123.