In 1963, the Uruguayan writer and journalist Eduardo Galeano went to China to interview the last emperor, Pu Yi. He and I were both working for Marcha, a Uruguayan weekly, at the time. Upon his return he commented about finding centuries-old Ming cups treated as useless garbage because they were cracked and had lost their functionality. This wasn’t meant as a critical remark; Galeano was just surprised at how the parameters for what was considered valuable differed across cultures.

A decade or two later I participated in a tour that took a group of visiting faculty through the art conservation program at SUNY Buffalo. They showed us an early twentieth-century mechanical toy that had been used for an exercise in restoration. In good shape, the object was probably worth less than $100, but the labor invested in restoring it was worth well over ten times that much. The result was impressive.

I thought about how the relationship between value and labor might act as a filter for posterity. Outside a classroom, it probably wouldn’t make sense to invest in conservation if the labor expenses involved exceeded the market value of the object. Instead, it would be classified as something disposable, the same fate that had awaited the chipped Ming cup in Mao’s China. In that case, the judgment turned on the question of functionality. In the toy’s case, the parameters were established by money. Both criteria affect legacy, determining what remains for future generations to encounter and what does not. Though a trivial insight, it hit me only then that the objects we use to understand different cultures are simply those that have been allowed to survive long enough to become symbols representing a set of relations we then define as culture.

In this sense, the collection of objects we inherit from the past is a legacy of values, and so becomes part of our education at the hands of history. Although such collections are often designed to flaunt power, they also demonstrate what value looks like for rising generations, shaping the way they think. Therefore the parameters that separate what will be preserved from what will not are as important as the objects that exemplify them. This problem is not limited to Ming cups or mechanical toys; it also extends to ideas. Ultimately, the parameters used for the preservation and elaboration of ideas are probably more important than those that apply to objects, since these precede them. Ideas determine if we see more in a Ming cup than the ability to drink from it, and they decide if the toy should be restored and conserved, and why.

This is why the disciplines emphasized in our educational institutions are at least as important as any content. For example, science, technology, engineering, and mathematics—the STEM curricula—have an ideological weight that affects institutional education long before a student even has a chance to decide if such an education is right for them. STEM, as the rhetoric around it tells us, is designed to secure a competitive advantage for the countries that embrace it over those that don’t. For obvious reasons, the humanities are understood to be less useful in this competition. Students are therefore educated not for their own betterment, or to leave a formative legacy for the future, but as foot soldiers in a national-corporate struggle. The number of universities in the US identifying as liberal arts colleges is down 39 percent from what is was twenty years ago, and the humanities—in particular, art programs—are shrinking for lack of funding and job prospects. In this landscape, the study of art is increasingly seen as a luxury associated with the leisure class.

The effect of this association is not hard to see. A couple of months ago, Pablo Helguera, another friend, posted on Facebook that he was invited to perform at an event that would require him to spend more money than he would receive as an honorarium. The post elicited an outpouring of sympathetic comments and other artists’ complaints about underpayment. Artists invariably receive a letter offering a “symbolic honorarium” which they are expected to accept with the understanding that the institution is embarrassed for the exploitation that they are nevertheless about to engage in. It’s true that not every institution is like Goldman Sachs. It’s also true that not every artist has the recognition value of Hillary Clinton. Therefore the term “symbolic honorarium” may be appropriate. On the one hand it reflects the lack of funds for this purpose even as those extending the invitation recognize that the arts are important to keep humanist cultural parameters in motion. On the other hand it also reveals an expectation on the part of the hosts that the artists, particularly younger and emerging ones, will feel honored by the invitation.

Recently I was invited to talk to a General Education class at Harvard. My symbolic honorarium was $250. There was a second event cofunded by a private foundation that raised the honorarium to $500. I should emphasize that both invitations had come from a friend of mine, and so I was performing to honor the friend’s request and not for my financial survival. However, I found out that in the General Studies Program, honoraria are capped at $250, which is, coincidentally, the recommended gratuity for a minister performing a funeral service. Given that the invitation required my researching and writing a special lecture—in addition to eight hours of travel—it was quite possible that when all was said and done, I would earn below minimum wage. I mentioned this to a law professor, whose response was: “What an honor to be invited by Harvard!” I don’t know if they have the same restrictions at the Harvard business or law schools, but I doubt it.

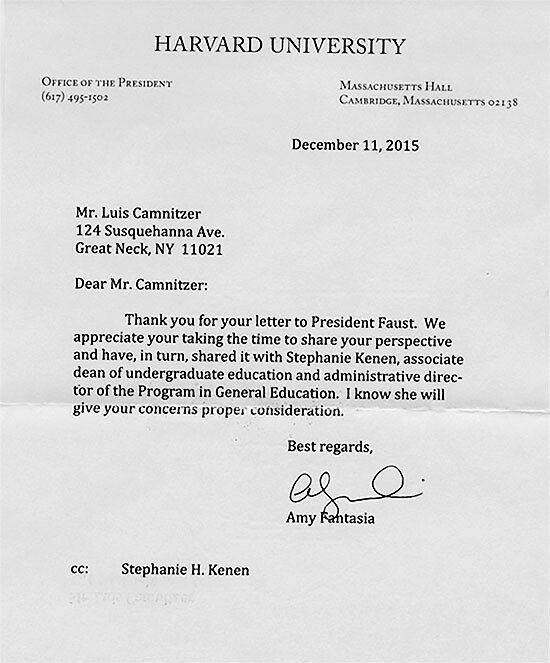

I decided to write to Harvard’s president, Drew Faust, less on my behalf than to spell out the general implications of unfair pay for intellectual work. She is an historian, I reasoned, so she would understand. (I received an answer some weeks later to the effect that the issue was being passed on to the administrative director of the Program in General Education. All correspondence is reproduced below).

Moreover, President Faust has made a point in her graduation speeches of encouraging students to do something other than working for Wall Street. It’s an odd suggestion in the context of Harvard’s reality, especially knowing that the school’s endowment managers make, on average, $8 million per year.

Of course, such disparities impact the future choices of any young person trained to figure out what is considered valuable and what isn’t, especially at a place like Harvard. I decided to share the correspondence with the The Harvard Crimson, and have yet to receive a response. Maybe underpayment has become so internalized that complaints of this nature are no longer news. Maybe artists have become the equivalent of cracked Ming Dynasty cups in Maoist China: objects that now fall outside the determining metric of value. But this metric is not a law of nature; it simply reflects the contemporary consensus, and this understanding can be shifted. For what it’s worth, I think that starting to fight for an International Fair Artists Remuneration Treaty may be a good and noisy strategy.

Luis Camnitzer

124 Susquehanna Ave.

Great Neck, NY 11021Dr. Drew Gilpin Faust

President, Harvard University

Massachusetts Hall

Cambridge, MA 02138November 25, 2015

Dear Dr. Faust

On October 13th I was invited to give a lecture at a course that is part of a program in General Education. I was asked to address extensively very specific questions, which meant that I had to write a special lecture for this purpose. The event implied ca. 20 hours writing and a day for travel. I compute this as a total of 28 hours. I was informed that the cap for honoraria for these events is $250.00, in my case the equivalent of $9.00 per hour.

I was warned that this was only a “symbolic honorarium,” which I interpreted favorably as meaning: “We are aware that you are worth much more, but we can’t afford it.” I know that Harvard is presently struggling economically. A 30% loss of the endowment caused by the 2008 recession, the payments to the administrators of the endowment apparently exceeding academic expenses, and the atypical low returns on investments bordering only 15% as compared to 17% for the University of Pennsylvania and 19% for Dartmouth, are bound to take to take a toll.

Having been raised and educated in Uruguay, I am familiar with the poverty problems suffered by educational institutions. They were even worse in my country, since education there is mostly free. So, I can only say that I am very sympathetic to your plight. I also know that as an artist I’m expected to perform acts of philanthropy and support as many worthy causes as I can. Selectively, I do this gladly.

Fortunately I’m economically secure, the same as most of your guest speakers in other programs (I am thinking in particular of both your respected School of Business and the Law School). As part of your distinguished guests, and presumably like them, I willingly join this group in accepting minimum wage for my services. However, I would like to point out that most of the artists you might or should consider inviting cannot truly afford this kind of remuneration. Most artists I know are unable to live from either consultancy or their production. They might still feel they have to service you for the honor of inclusion. However, to ask them to lecture for this honor and at this rate of payment would not only be unfair, but also exploitative and below the standards that you probably espouse. On the other hand, favoring relatively affluent artists to report on their thoughts and production to your students poses the danger of giving them a distorted view of US and international culture.

I am sharing all these thoughts, experience, and my feelings with you because they have prompted me to found the “International Fair Artists Remuneration Treaty.” I may list Harvard as one of the prominent seed organizations for this project.

Wishing your institution a prompt economic recovery, I send you my highest regards.

Luis Camnitzer

Luis Camnitzer

124 Susquehanna Ave.

Great Neck, NY 11021Meg Bernhard

Managing Editor

The Harvard Crimson

14 Plympton St.

Cambridge, MA 02138January 23, 2016

Dear Ms. Bernhard,

Over the last several months many artists have been complaining on social media pages about the increasingly prevalent pattern of underpayment when invited as guest speakers by academic institutions. In October I had the experience myself at Harvard, and while in my case it wasn’t a hardship I think the time has come to call universities to account for their exploitation of artists. Their intellectual contributions should be valued to the same degree as those of guest speakers in other fields and disciplines. In a society that prioritizes STEM and has at the same time become increasingly oligarchical, it’s the artists and humanists who are the protectors of sanity and should be rewarded sanely.

On December 11th, I received a letter from the office of the President informing me that the matter was being referred to Associate Dean Stephanie Kenen. There has been no further communication.

Since downgrading the arts affects the quality of academic life and the education of students, I felt the topic might be of interest to your publication. I also think The Harvard Crimson is better equipped than I am to inquire if any consideration is being given to the problem I tried to raise with Dr. Faust.

Sincerely,

Luis Camnitzer