The central question to be asked about art is this one: Is art capable of being a medium of truth? This question is central to the existence and survival of art because if art cannot be a medium of truth then art is only a matter of taste. One has to accept the truth even if one does not like it. But if art is only a matter of taste, then the art spectator becomes more important than the art producer. In this case art can be treated only sociologically or in terms of the art market—it has no independence, no power. Art becomes identical to design.

Now, there are different ways in which we can speak about art as a medium of truth. Let me take one of these ways. Our world is dominated by big collectives: states, political parties, corporations, scientific communities, and so forth. Inside these collectives the individuals cannot experience the possibilities and limitations of their own actions—these actions become absorbed by the activities of the collective. However, our art system is based on the presupposition that the responsibility for producing this or that individual art object, or undertaking this or that artistic action, belongs to an individual artist alone. Thus, in our contemporary world art is the only recognized field of personal responsibility. There is, of course, an unrecognized field of personal responsibility—the field of criminal actions. The analogy between art and crime has a long history. I will not go into it. Today I would, rather, like to ask the following question: To what degree and in what way can individuals hope to change the world they are living in? Let us look at art as a field in which attempts to change the world are regularly undertaken by artists and see how these attempts function. In the framework of this text, I am not so much interested in the results of these attempts as the strategies that the artists use to realize them.

Indeed, if artists want to change the world the following question arises: In what way is art able to influence the world in which we live? There are basically two possible answers to this question. The first answer: art can capture the imagination and change the consciousness of people. If the consciousness of people changes, then the changed people will also change the world in which they live. Here art is understood as a kind of language that allows artists to send a message. And this message is supposed to enter the souls of the recipients, change their sensibility, their attitudes, their ethics. It is, let’s say, an idealistic understanding of art—similar to our understanding of religion and its impact on the world.

However, to be able to send a message the artist has to share the language that his or her audience speaks. The statues in ancient temples were regarded as embodiments of the gods: they were revered, one kneeled down before them in prayer and supplication, one expected help from them and feared their wrath and threat of punishment. Similarly, the veneration of icons has a long history within Christianity—even if God is deemed to be invisible. Here the common language had its origin in the common religious tradition.

However, no modern artist can expect anyone to kneel before his work in prayer, seek practical assistance from it, or use it to avert danger. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, Hegel diagnosed this loss of a common faith in embodied, visible divinities as the reason for art losing its truth: according to Hegel the truth of art became a thing of the past. (He speaks about pictures, thinking of the old religions vs. invisible law, reason, and science that rule the modern world.) Of course, in the course of modernity many modern and contemporary artists have tried to regain a common language with their audiences by the means of political or ideological engagement of one sort or another. The religious community was thus replaced by a political movement in which artists and their audiences both participated.

However, art, to be politically effective, to be able to be used as political propaganda, has to be liked by its public. But the community that is built on the basis of finding certain artistic projects good and likable is not necessarily a transformative community—a community that can truly change the world. We know that to be considered as really good (innovative, radical, forward looking), modern artworks are supposed to be rejected by their contemporaries—otherwise, these artworks come under suspicion of being conventional, banal, merely commercially oriented. (We know that politically progressive movements were often culturally conservative—and in the end it was this conservative dimension that prevailed.) That is why contemporary artists distrust the taste of the public. And the contemporary public, actually, also distrusts its own taste. We tend to think that the fact that we like an artwork could mean that this artwork is not good enough—and the fact that we do not like an artwork could mean that this artwork is really good. Kazimir Malevich believed that the greatest enemy of the artist is sincerity: artists should never do what they sincerely like because they probably like something that is banal and artistically irrelevant. Indeed, the artistic avant-gardes did not want to be liked. And—what is even more important—they did not want to be “understood,” did not want to share the language which their audience spoke. Accordingly, the avant-gardes were extremely skeptical toward the possibility of influencing the souls of the public and building a community of which they would be a part.

At this point the second possibility to change the world by art comes into play. Here art is understood not as the production of messages, but rather as the production of things. Even if artists and their audience do not share a language, they share the material world in which they live. As a specific kind of technology art does not have a goal to change the soul of its spectators. Rather, it changes the world in which these spectators actually live—and by trying to accommodate themselves to the new conditions of their environment, they change their sensibilities and attitudes. Speaking in Marxist terms: art can be seen as a part of the superstructure or as a part of the material basis. Or, in other words, art can be understood as ideology or as technology. The radical artistic avant-gardes pursued this second, technological way of world transformation. They tried to create new environments that would change people through puttting them inside these new environments. In its most radical form this concept was pursued by the avant-garde movements of the 1920s: Russian constructivism, Bauhaus, De Stijl. The art of the avant-garde did not want to be liked by the public as it was. The avant-garde wanted to create a new public for its art. Indeed, if one is compelled to live in a new visual surrounding, one begins to accommodate one’s own sensibility to it and learn to like it. (The Eiffel Tower is a good example.) Thus, the artists of the avant-garde also wanted to build a community—but they didn’t see themselves as a part of this community. They shared with their audiences a world—but not a language.

Of course, the historical avant-garde itself was a reaction to the modern technology that permanently changed and still changes our environment. This reaction was ambiguous. The artists felt a certain affinity with the artificiality of the new, technological world. But at the same time they were irritated by the lack of direction and ultimate purpose that is characteristic of technological progress. (Marshall McLuhan: artists moved from the ivory tower to the control tower.) This goal was understood by the avant-garde as the politically and aesthetically perfect society—as utopia, if one is still ready to use this word. Here utopia is nothing else but the end stage of historical development—a society that is in no further need of change, that does not presuppose any further progress. In other words, artistic collaboration with technological progress had the goal of stopping this progress.

This conservatism—it can also be a revolutionary conservatism—inherent to art is in no way accidental. What is art then? If art is a kind of technology, then the artistic use of technology is different from the nonartistic use of it. Technological progress is based on a permanent replacement of old, obsolete things by new (better) things. (Not innovation but improvement—innovation can only be in art: the black square.) Art technology, on the contrary, is not a technology of improvement and replacement, but rather of conservation and restoration—technology that brings the remnants of the past into the present and brings things of the present into the future. Martin Heidegger famously believed that in this way the truth of art is regained: by stopping technological progress at least for a moment, art can reveal the truth of the technologically defined world and the fate of the humans inside this world. However, Heidegger also believed that this revelation is only momentary: in the next moment, the world that was opened by the artwork closes again—and the artwork becomes an ordinary thing that is treated as such by our art institutions. Heidegger dismisses this profane aspect of the artwork as irrelevant for the essential, truly philosophical understanding of art—because for Heidegger it is the spectator who is the subject of such an essential understanding and not the art dealer or museum curator.

And, indeed, even if the museum visitor sees the artworks as isolated from profane, practical life, the museum staff never experiences the artworks in this sacralized way. The museum staff does not contemplate artworks but regulates the temperature and humidity level in the museum spaces, restores these artworks, removes the dust and dirt from them. In dealing with the artworks there is the perspective of the museum visitor—but there is also the perspective of the cleaning lady who cleans the museum space as she would clean any other space. The technology of conservation, restoration, and exhibition are profane technologies—even if they produce objects of aesthetic contemplation. There is a profane life inside the museum—and it is precisely this profane life and profane practice that allow the museum items to function as aesthetic objects. The museum does not need any additional profanation, any additional effort to bring art into life or life into art—the museum is already profane through and through. The museum, as well as the art market, treat artworks not as messages but as profane things.

Usually, this profane life of art is protected from the public view by the museum’s walls. Of course, at least from the beginning of the twentieth century art of the historical avant-garde tried to thematize, to reveal the factual, material, profane dimension of art. However, the avant-garde never fully succeeded in its quest for the real because the reality of art, its material side that the avant-garde tried to thematize, was permanently re-aestheticized—these thematizations having been put under the standard conditions of art representation. The same can be said of institutional critique, which also tried to thematize the profane, factual side of art institutions. Institutional critique also remained inside art institutions. Now, I would argue that this situation has changed in recent years—due to the internet and to the fact that the internet has replaced traditional art institutions as the main platform for the production and distribution of art. The internet thematizes precisely the profane dimension of art. Why? The answer to this question is simple enough: in our contemporary world the internet is the place of production and exposure of art at the same time.

This represents a significant departure from past modes of artistic production. As I’ve noted previously:

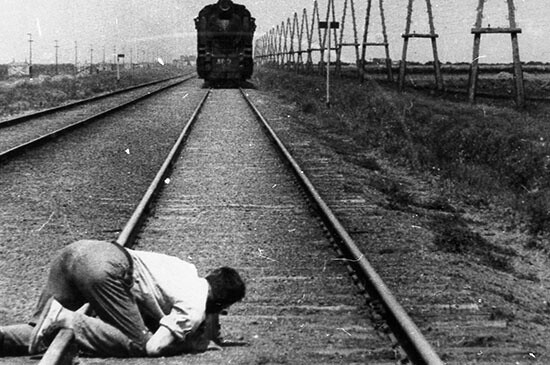

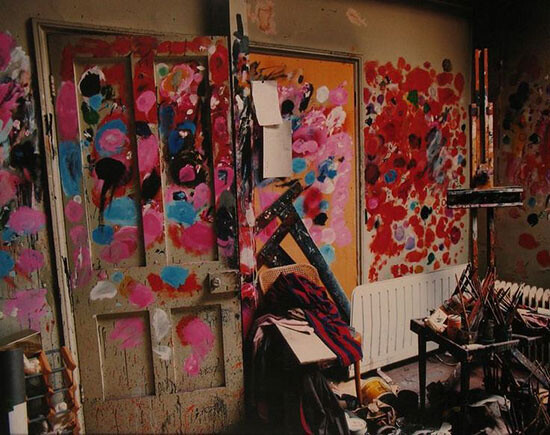

Traditionally, the artist produced an artwork in his or her studio, hidden from public view, and then exhibited a result, a product—an artwork that accumulated and recuperated the time of absence. This time of temporary absence is constitutive for what we call the creative process—in fact, it is precisely what we call the creative process.

André Breton tells a story about a French poet who, when he went to sleep, put on his door a sign that read: “Please, be quiet—the poet is working.” This anecdote summarizes the traditional understanding of creative work: creative work is creative because it takes place beyond public control—and even beyond the conscious control of the author. This time of absence could last days, months, years—even a whole lifetime. Only at the end of this period of absence was the author expected to present a work (maybe found in his papers posthumously) that would then be accepted as creative precisely because it seemed to emerge out of nothingness.1

In other words, creative work is work that presupposes the desynchronization of the time of work and the time of the exposure of the results of this work. The reason is not that the artist has committed a crime or has a dirty secret he or she wants to keep from the gaze of others. The gaze of others is experienced by us as an evil eye not when it wants to penetrate our secrets and make them transparent (such a penetrating gaze is rather flattering and exciting), but when it denies that we have any secrets, when it reduces us to what it sees and registers—when the gaze of others banalizes, trivializes us. (Sartre: the other is hell, the gaze of the other denies us our project. Lacan: the eye of the other is always an evil eye.)

Today the situation has changed. Contemporary artists work using the internet—and also put their work on the internet. Artworks by a particular artist can be found on the internet when I google the name of this artist—and they are shown to me in the context of other information that I find on the internet about this artist: biography, other works, political activities, critical reviews, details of the artist’s personal life, and so forth. Here I mean not the fictional, authorial subject allegedly investing the artwork with his intentions and with meanings that should be hermeneutically deciphered and revealed. This authorial subject has already been deconstructed and proclaimed dead many times over. I mean the real person existing in the off-line reality to which the internet data refers. This author uses the internet not only to produce art, but also to buy tickets, make restaurant reservations, conduct business, and so forth. All these activities take place in the same integrated space of the internet—and all of them are potentially accessible to other internet users. Here the artwork becomes “real” and profane because it becomes integrated into the information about its author as a real, profane person. Art is presented on the internet as a specific kind of activity: as documentation of a real working process taking place in the real, off-line world. Indeed, on the internet art operates in the same space as military planning, tourist business, capital flows, and so forth: Google shows, among other things, that there are no walls in internet space. A user of the internet does not switch from the everyday use of things to their disinterested contemplation—the internet user uses the information about art in the same way in which he or she uses information about all other things in the world. It is as if we have all become the museum’s or gallery’s staff—art being documented explicitly as taking place in the unified space of profane activities.

The word “documentation” is crucial here. During recent decades the documentation of art has been more and more included in art exhibitions and art museums—alongside traditional artworks. But this arena has always seemed highly problematic. Artworks are art—they immediately demonstrate themselves as art. So they can be admired, emotionally experienced, and so forth. But art documentation is not art: it merely refers to an art event, or exhibition, or installation, or project which we assume has really taken place. Art documentation refers to art but it is not art. That is why art documentation can be reformatted, rewritten, extended, shortened, and so forth. One can subject art documentation to all these operations that are forbidden in the case of an artwork because these operations change the form of the artwork. And the form of the artwork is institutionally guaranteed because only the form guarantees the reproducibility and identity of this artwork. On the contrary, the documentation can be changed at will because its identity and reproducibility is guaranteed by its “real,” external referent and not by its form. But even if the emergence of art documentation precedes the emergence of the internet as an art medium, only the introduction of the internet has given art documentation a legitimate place. (Here one can say like Benjamin noted: montage in art and cinema).

Meanwhile, art institutions themselves have begun to use the internet as a primary space for their self-representation. Museums put their collections on display on the internet. And, of course, digital depositories of art images are much more compact and much cheaper to maintain than traditional art museums. Thus, museums are able to present the parts of their collections that are usually kept in storage. The same can be said about the websites of individual artists—one can find there the fullest representation of what they are doing. It is what artists usually show to visitors who come to their studios nowadays: if one comes to a studio to see a particular artist’s work, this artist usually puts a laptop on the table and shows the documentation of his or her activities, including production of artworks but also his or her participation in long-term projects, temporary installations, urban interventions, political actions, and so forth. The actual work of the contemporary artist is his or her CV.

Today, artists, like other individuals and organizations, try to escape total visibility by creating sophisticated systems of passwords and data protection. As I’ve argued in the past, with regard to internet surveillance:

Today, subjectivity has become a technical construction: the contemporary subject is defined as an owner of a set of passwords that he or she knows—and that other people do not know. The contemporary subject is primarily a keeper of a secret. In a certain sense, this is a very traditional definition of the subject: the subject was long defined as knowing something about itself that only God knew, something that other people could not know because they were ontologically prevented from “reading one’s thoughts.” Today, however, being a subject has less to do with ontological protection, and more to do with technically protected secrets. The internet is the place where the subject is originally constituted as a transparent, observable subject—and only afterwards begins to be technically protected in order to conceal the originally revealed secret. However, every technical protection can be broken. Today, the hermeneutiker has become a hacker. The contemporary internet is a place of cyber wars in which the prize is the secret. And to know the secret is to control the subject constituted by this secret—and the cyber wars are the wars of this subjectivation and desubjectivation. But these wars can take place only because the internet is originally the place of transparency …

The results of surveillance are sold by the corporations that control the internet because they own the means of production, the material-technical basis of the internet. One should not forget that the internet is owned privately. And its profit comes mostly from targeted advertisements. This leads to an interesting phenomenon: the monetization of hermeneutics. Classical hermeneutics, which searched for the author behind the work, was criticized by the theoreticians of structuralism, close reading, and so forth, who thought that it made no sense to chase ontological secrets that are inaccessible by definition. Today this old, traditional hermeneutics is reborn as a means of economically exploiting subjects operating on the internet, where all the secrets are supposedly revealed. The subject is here no longer concealed behind his or her work. The surplus value that such a subject produces and that is appropriated by internet corporations is the hermeneutic value: the subject not only does something on the internet, but also reveals him- or herself as a human being with certain interests, desires, and needs. The monetization of classical hermeneutics is one of the most interesting processes that has emerged in recent decades. The artist is interesting not as producer but as consumer. Artistic production by a content provider is only a means of anticipating this content provider’s future consumption behavior—and it is this anticipation alone that is relevant here because it brings profit.2

But here the following question emerges: who is the spectator on the internet? The individual human being cannot be such a spectator. But the internet also does not need God as its spectator—the internet is big but finite. Actually, we know who the spectator is on the internet: it is the algorithm—like algorithms used by Google and the NSA.

But now let me return to the initial question concerning the truth of art—understood as a demonstration of the possibilities and limitations of the individual’s actions in the world. Earlier I discussed artistic strategies designed to influence the world: by persuasion or by accommodation. Both of these strategies presuppose what can be named the surplus of vision on the part of the artist—in comparison to the horizon of his or her audience. Traditionally, the artist was considered to be an extraordinary person who was able to see what “average,” “normal” people could not see. This surplus of vision was supposed to be communicated to the audience by the power of the image or by the force of technological change. However, under the conditions of the internet the surplus of vision is on the side of the algorithmic gaze—and no longer on the side of the artist. This gaze sees the artist, but remains invisible to him (at least insofar as the artist will not begin to create algorithms—which will change artistic activity because they are invisible—but will only create visibility). Perhaps artists can still see more than ordinary human beings—but they see less than the algorithm. Artists lose their extraordinary position—but this loss is compensated: instead of being extraordinary the artist becomes paradigmatic, exemplary, representative.

Indeed, the emergence of the internet leads to an explosion of mass artistic production. In recent decades artistic practice has become as widespread as, earlier, only religion and politics were. Today we live in times of mass art production, rather than in times of mass art consumption. Contemporary means of image production, such as photo and video cameras, are relatively cheap and universally accessible. Contemporary internet platforms and social networks like Facebook, YouTube, and Instagram allow populations around the global to make their photos, videos, and texts universally accessible—avoiding control and censorship by traditional institutions. At the same time, contemporary design makes it possible for the same populations to shape and experience their apartments or workplaces as artistic installations. And diet, fitness, and cosmetic surgery allow them to fashion their bodies into art objects. In our times almost everyone takes photographs, makes videos, write texts, documents their activities—and then puts the documentation on the internet. In earlier times we talked about mass cultural consumption, but today we have to speak about mass cultural production. Under the condition of modernity the artist was a rare, strange figure. Today there is nobody who is not involved in artistic activity of some kind.

Thus, today everybody is involved in a complicated play with the gaze of the other. It is this play that is paradigmatic of our time, but we still don’t know its rules. Professional art, though, has a long history of this play. The poets and artists of the Romantic period already began to see their own lives as their actual artworks. Nietzsche says in his Birth of Tragedy that to be an artwork is better than to be an artist. (To become an object is better than to become a subject—to be admired is better than to admire.) We can read Baudelaire’s texts about the strategy of seduction, and we can read Roger Caillois and Jacques Lacan on the mimicry of the dangerous or on luring the evil gaze of the other into a trap by means of art. Of course, one can say that the algorithm cannot be seduced or frightened. However, this is not what is actually at stake here.

Artistic practice is usually understood as being individual and personal. But what does the individual or personal actually mean? The individual is often understood as being different from the others. (In a totalitarian society, everyone is alike. In a democratic, pluralistic society, everyone is different—and respected as being different.) However, here the point is not so much one’s difference from others but one’s difference from oneself—the refusal to be identified according to the general criteria of identification. Indeed, the parameters that define our socially codified, nominal identity are foreign to us. We have not chosen our names, we have not been consciously present at the date and place of our birth, we have not chosen our parents, our nationality, and so forth. All these external parameters of our personality do not correlate to any subjective evidence that we may have. They indicate only how others see us.

Already a long time ago modern artists practiced a revolt against the identities which were imposed on them by others—by society, the state, schools, parents. They affirmed the right of sovereign self-identification. They defied expectations related to the social role of art, artistic professionalism, and aesthetic quality. But they also undermined the national and cultural identities that were ascribed to them. Modern art understood itself as a search for the “true self.” Here the question is not whether the true self is real or merely a metaphysical fiction. The question of identity is not a question of truth but a question of power: Who has the power over my own identity—I myself or society? And, more generally: Who exercises control and sovereignty over the social taxonomy, the social mechanisms of identification—state institutions or I myself? The struggle against my own public persona and nominal identity in the name of my sovereign persona or sovereign identity also has a public, political dimension because it is directed against the dominating mechanisms of identification—the dominating social taxonomy, with all its divisions and hierarchies. Later, these artists mostly gave up the search for the hidden, true self. Rather, they began to use their nominal identities as ready-mades—and to organize a complicated play with them. But this strategy still presupposes a disidentification from nominal, socially codified identities—with the goal of artistically reappropriating, transforming, and manipulating them. The politics of modern and contemporary art is the politics of nonidentity. Art says to its spectator: I am not what you think I am (in stark contrast to: I am what I am). The desire for nonidentity is, actually, a genuinely human desire—animals accept their identity but human animals do not. It is in this sense that we can speak about the paradigmatic, representative function of art and artist.

The traditional museum system is ambivalent in relation to the desire for nonidentity. On the one hand, the museum offers to the artist a chance to transcend his or her own time, with all its taxonomies and nominal identities. The museum promises to carry the artist’s work into the future. However, the museum betrays this promise at the same moment it fulfills it. The artist’s work is carried into the future—but the nominal identity of the artist becomes reimposed on his or her work. In the museum catalogue we still read the artist’s name, date and place of birth, nationality, and so forth. (That is why modern art wanted to destroy the museum.)

Let me conclude by saying something good about the internet. The internet is organized in a less historicist way than traditional libraries and museums. The most interesting aspect of the internet as an archive is precisely the possibilities for decontextualization and recontextualization through the operations of cut and paste that the internet offers its users. Today we are more interested in the desire for nonidentity that leads artists out of their historical contexts than in these contexts themselves. And it seems to me that the internet gives us more chances to follow and understand the artistic strategies of nonidentity than traditional archives and institutions.