Continued from “Neoliberalism and the New Afro-Pessimism: Djibril Diop Mambéty’s Hyènes”

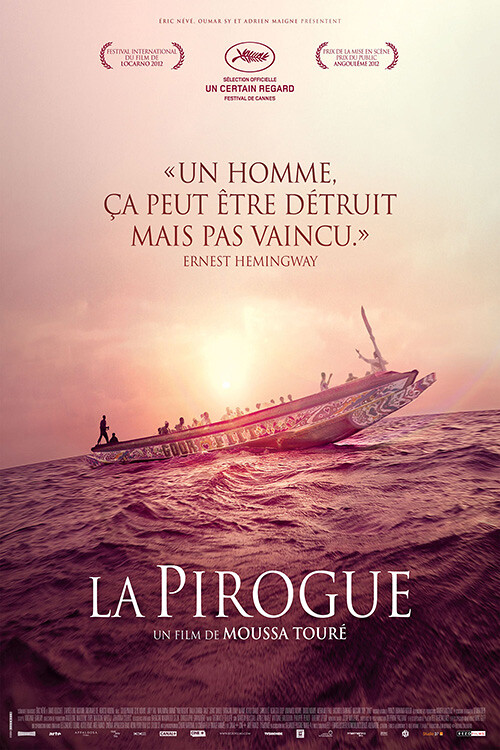

Let’s return to this galaxy, this solar system, this planet—indeed, the continent, Africa, that gave birth to an animal that can reflect on planets, solar systems, galaxies, and even the possibility of multi-verses. The movie is The Pirogue. It’s directed by Moussa Touré. It begins in Senegal, and has a young fisherman, Baye Laye (played by Souleymane Seye Ndiaye), as its central character. Baye’s life is not bad, but clearly more money would make things easier. One day, a local entrepreneur offers him lots of what he lacks, cash, to transport thirty black Africans to Spain. The trip is estimated to take seven days.

Baye’s boat is not tiny but is by no means big enough to guarantee anything like a safe journey across a major body of water. But the bleakness of the economic conditions of post-postcolonial Senegal—or rather neoliberal, post-Fanon, afro-pessimist Senegal (which I previously described as being inaugurated by Diop Mambéty’s film Hyènes)—make these very poor odds of success and the high risk involved acceptable to the imagination.

Those attempting this very dangerous trip are not insane, nor are they terribly poor. Their minds are in fine working order, and, more importantly, they are wealthy enough to make the massive thousand-euro bet against the unknown between the shores of the continents, and the greater unknown beyond the walls of Fortress Europe and into the lands of the inhabitant.1 The people on the boat leave Africa as citizens, and if they are lucky, they will enter Europe and become inhabitants.

What is an inhabitant? He or she issues from the citizen. What is a citizen? He or she is the ultimate unit of a state, and he or she has obligations to this state, and the state has obligations to this he or she—the one who has made an agreement with many others to imagine the nation’s borders, order, and laws. The citizen emerged from the premodern (feudal) subject, and from the citizen emerges the inhabitant, who lives inside a nation but outside its democratic or governing institutions.

Whereas the citizen subject is a body and a state, the inhabitant is just his/her land and body—a will, a unit not of a state but of organs and the plain moral right to maintain the health of those organs. By not being committed to democracy in its national form, the inhabitant occupies a space—a very open space—that does not construct a radically new kind of subjectivity so much as expose what is most human in humans. It is at this moment of exposure that the inhabitant encounters and passes through its opposite: the stateless cosmopolitanism of the global managerial class.

One of Baye’s passengers cracks almost immediately after the ship leaves the coast of Africa. When the land vanishes, he realizes that reasoning on solid ground (I cross the sea, I reach Europe, I get a job, I send money back home, I save money, I maybe open a shop) is not the same as reasoning on the sea (this water will take us nowhere but more water and will not end until everything is water). He suddenly understands the true scale of the danger and wants to go back home, back to land. But there is no turning back. It’s now Europe or death.

Another passenger explains that he dreams of becoming a musician in Paris. Another hopes to get a new leg in Spain (he lost his real one in another boat that crashed while attempting to cross the same sea). Another passenger wants to be just like his brother, who has his papers in order and is doing well as a mechanic in France. This is a ship of dreams that can be dashed by just one powerful wave.

But this story as a story is already old hat. We read about these kinds of journeys in the papers and on the web all the time. They provide a steady living for hundreds of European journalists. Even the story as a movie is hardly exceptional, as it’s one among several feature films on the subject. There is even a romantic comedy, Paris, that assumes the crisis to have become so routine that it can be romanticized—the fragile boat, the dreamy lover, the dangerous Mediterranean, the deepening twilight. So on its own, The Pirogue’s scenario really adds nothing new to what other movies and mainstream media have already narrated or reported over and over again. And it would have already slipped from its place on the screen to merge with all those eye-grabbing headlines (“From Africa to Europe: A Surprisingly Dangerous Journey for Migrants,” “Sea of Chaos and Despair for African Refugees,” “Europe Brings Risk and Heartbreak”) if it weren’t for one important sequence. It is brief, yet it means everything, and it occurs not long after the journey begins.

While cutting across a sea whose calm becomes unsettling, the boat encounters another boat. The other boat looks just like the first one, and, indeed, had the same purpose until its engine died. The people on the other boat have been drifting for days and are desperate for water and food. The sea is another kind of desert. They scream for help, they wave their hands wildly, some dive into the sea and splash-swim towards their last chance in the world.

But this other boat poses many problems for the Senegalese fisherman and his passengers. Is there enough food to feed those who want to come aboard, in addition to those already aboard? The Senegalese fisherman didn’t calculate the extra weight and trouble of the others into the trip, into the size and the estimated resilience of the fishing vessel, which has only two engines: one in use, and another as backup. The most rational thing for the most rational animal to do would be to not stop to rescue the other migrants, and to continue on as if nothing happened. This decision is clearly correct because it makes perfect sense. Better for some to survive than for all to go under. Reason deals with facts, which are often indifferent to or divorced from precisely what appeals to the emotions: the present moment. Reason weighs events in the past and makes calculations about what is likely to happen in the future. The extreme version of this is called Laplace’s demon. This demon is not about how you feel about things, but the hard laws of matter in the universe.

But here is the heart of Touré’s The Pirogue, and if you miss it, you have missed the movie. This is not, it turns out, a dramatization of the headline horrors of watery mass graves, wave-dashed dreams, sinking pregnant women in crepuscular water, and dead babies common to those of the myth of Drexciya. This is a very direct statement about the nature of our humanity.

When the fisherman and his passengers decide not to help the others, they decisively break with something profoundly human. And such a break must have serious spiritual consequences. The animal we are is human, and that is our nature, our being, our species spirit. A heavy silence falls on the boat. Each traveler has turned inward and must now confront the question: What kind of animal have you become when you no longer behave like a human? What is your spirit? This question also appears in Mambéty’s Hyènes. But that film asks a question and provides an answer that is deeply pessimistic. In The Pirogue, the characters ask themselves this question, and soon they fear the terrible answer that faces them.

The headlines exit. The moral universe enters.

Things start going wrong after making this defining decision. The engine dies, but there is another one. Then that engine dies. We might accept this as some serious bad luck (the engines never looked reliable to begin with), but then a storm erupts out of nowhere. The clouds explode. The wind screams. Thunder cracks. The waves crash. The boat is tossed about. Some passengers are thrown overboard. We realize that the storm is not natural but supernatural.

But why has a film that’s been so realistic, so meticulous in its descriptions of characters, their backgrounds, their hopes, the money they paid for the trip, the distance they have to travel to reach the good life, the sea-worthiness of the boat they are on, suddenly take a turn toward the fantastic?

Indeed, the real events leading to the tragedy of a Libyan fishing trawler in April 2015 (the headlines: “700 migrants feared dead in Mediterranean shipwreck,” “Hundreds of Migrants Are Feared Dead as Ship Capsizes Off Libyan Coast,” “EU leaders call for emergency talks after 700 migrants drown off Libya”) almost match those in the movie The Pirogue: entrepreneurs want a trained fisherman to “pilot the voyage,”2 the fisherman reluctantly agrees to do the job, people pay lots of money to reach Europe, and so on. But whereas the Libyan fishing journey ended with a banal miscalculation by the ship’s captain, the journey in The Pirogue ends biblically.

But why, after the incident with the stranded ship, did the director of The Pirogue, Touré, depart from realism and enter the paranormal universe of: “The Lord sent out a great wind into the sea, and there was a mighty tempest in the sea, so that the ship was like to be broken”?3 Why did he not just make it a matter of an error or poor judgment by the captain? True, a storm is much more cinematic, but there is much more to it than that.

The decision not to rescue the other humans provokes moral outrage. And this outrage takes the form of a storm that destroys the boat and kills several would-be migrants. Had they done the moral thing, the right thing (helped the stranded humans), the weather and the outcome of the trip would have been different. The director would not, like an angry god, have punished his characters.4

But the god of The Pirogue seems to be a touch unreasonable; after all, the fisherman and passengers were not cruel or evil. On the surface of things, it seems a bit unfair. They made a tough decision that was in essence rational. How can they be punished for this? Why did the director not sympathize with the difficulty of his characters’ circumstances? Is this maybe a cultural thing—are Africans just superstitious people who don’t understand that we must make rational decisions in a secular and scientific world?5

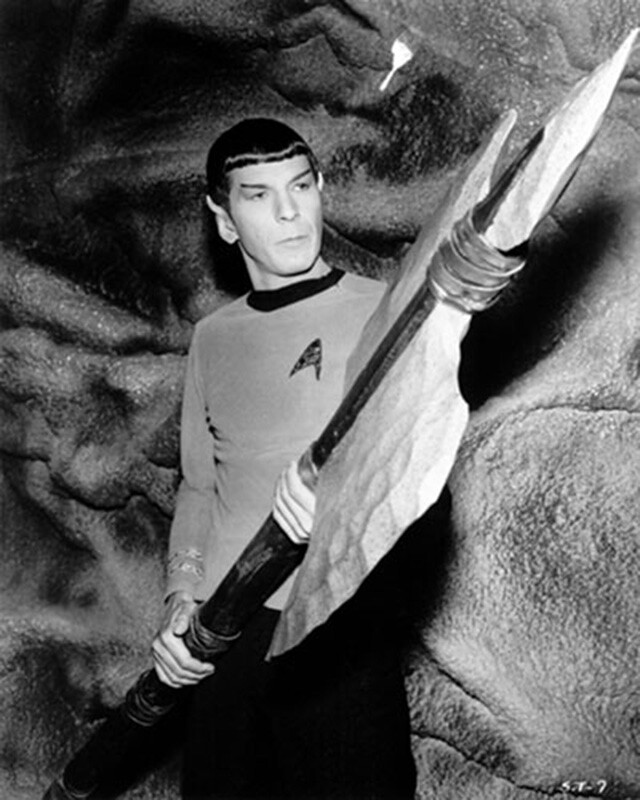

No, the reason for the film’s fantastic god-mad storm has its roots in basic biology, in the human body, the genes. We are moral not because of supernatural reasons but because of how we evolved over thousands of years. We are no more the rational animal than the moral one. A space ape like Star Trek’s Mr. Spock is a rational animal. But Earth apes like us evolve in a completely different direction. A very basic but important question then presents itself: What is morality?

The answer is simple: morality is the maintenance of equality between humans. What is right and what is wrong always involves situations that either increase or decrease a group’s equality. Truly moral actions are always equalizers. They rebalance a situation that has broken with this equilibrium. This is all morality can really mean. Anything beyond this definition is a distortion, distraction, or pure nonsense.6

What must not be forgotten or missed is that moral behavior thrives best in social contexts that are egalitarian, in societies committed to equality. A moral animal is not just social (most ant colonies are social without having morality) but rather practices a form of sociality in which one maintains his/her equality with all members of his/her group. Other social formations can be hierarchical, and this may lead to complicated political arrangements, but not to morality. Politics does not lead to morality, but the rupture in a moral order can regress into politics.

In an egalitarian order, one does not follow rules out of fear of those above them but out of an innate sense of responsibility to those around them. Politics is about alliances that grab for power or attempt to redistribute power. Egalitarianism does not so much distribute power as keep it in constant check. Chimpanzees are more political, and therefore less egalitarian, and therefore less moral, than humans.7

So what did the fisherman and his passengers do that was so immoral? And why were they punished by God? Because they did not restore to a state of equality the humans from the other boat who pleaded for their help. They entered an unequal situation and left it as just that: unequal. And this is precisely what the plea for help is: make me equal to you. If it is in your power to restore equality (meaning, if your position is better than that of the one who needs and wants help), and you do not, this is sin in its original sense. We have only this apple in the human garden.

The forms of equalization: from a person who is hungry to a person who has food to eat; from a person who is sick to a person in good health8; from a person who is stranded at sea to a person on a functioning boat. To not help is to break with the essence of human morality, which is to either reinforce or reinstate equality. And this break is felt so powerfully that its force can disrupt the order of nature: all the stars fall at once, birds fall out of the sky, lions appear on downtown streets.

But where did these egalitarian feelings come from? And why are they so powerful that, as in the mythical themes of films such as Star Wars, many believe that they structure not only our minds and our lives, but the entirety of the universe?9 As there is a negative charge and positive charge, antimatter and matter, forces of attraction and repulsion, there is good and evil.10 And what is good is equality, and what is bad is inequality. What made us this kind of animal? The answer is simple: We are not a strong animal; we are essentially weak. Our closest relative, the chimpanzee, is, according to evolutionary biologist Alan Walker, four times stronger than the average human. We don’t even have sharp teeth. Our development is terribly slow. Our big brains take twenty-one years to fully develop. Our babies are completely useless. Unlike chimpanzees and gorillas, our women need assistance during childbirth. They need help.11 Humans are even terrible sprinters, as much as we admire Usain Bolt. Few things in nature are more doomed than a human who is alone and left to fend for him- or herself.

Our survival has depended on dependency.12 “To man … there is nothing more useful than man.”13 From this dependency arose our cooperative behavior. We did not become a hypersocial animal because it was a good idea, but because we had no other choice. Strong individuals would have led us to our extinction, which is why we used to punish them, to keep them in check. (I refer you to my previous essay on Hyènes, because egalitarian justice is where dependency and cooperative behavior make their most important link.) As these prosocial behaviors shaped the world around us, this reshaped world began to shape us culturally and physically. And also genetically.

The rising and falling of the sun is reflected in our genes, which is why we have good reason to worship the sun.14 So it comes as no surprise that our genetic morality captured our galactic imagination.15 That’s Star Wars. That’s the force. That’s the biblical struggle between Heaven and Hell, and that’s what transforms the calm seas of The Pirogue into a raging storm.

The per-capita income of Senegal in the year The Pirogue was made (2012) was 1,700 euros, and trips across the sea on a fishing skiff can cost up to 2,600 euros.

A Reuters story posted on April 25, 2015 reported that the brother of the ship’s captain claimed that the latter was forced by a greedy gang to take the dangerous job: “My brother was recruited by Libyans to work in a cafe in Libya a few weeks ago, but afterwards he was forced under threat by smugglers to pilot the voyage because he knows a little about the sea and worked with our father fishing” →

Jonah 4, King James Bible.

Here is a crucial scene from the excellent Italian film Terraferma: Three Italian fishermen spot a large number of black Africans stranded on a flimsy lifeboat in the open sea. The black Africans wave and yell for help. The owner of the fishing boat, Ernesto (Mimmo Cuticchio), radios the coast guard and gives them information about the situation. The coast guard orders the fisherman not to go near the Africans but also not to leave the area until their patrol boat arrives. Suddenly, one by one, some of the desperate Africans jump into the sea and attempt to swim toward the fishing boat. Ernesto then decides to move closer to the Africans and help them out of the dangerous sea. But another fisherman reminds him that it is against the law to help illegal immigrants. (This is the rational thing to do.) But the owner of the boat responds: “I’ve never left people on the sea.” (This is not the rational thing to do.) It is that moral code, however, that moral certainty, that is at the heart of Terraferma: these are not Africans, stateless illegals, or whatever; these are humans. The Pirogue, of course, has the exact same situation: sea-stranded black Africans calling for help from a passing boat. But this time the captain of the passing boat is a black African who is transporting black Africans to Europe. This captain does not make the same decision as Ernesto, and so empties his entire trip and trade of all moral substance. (I use “substance” here in a Spinozistic sense—the moral is the all of our species being.)

Linton Kwesi Johnson’s “Reality Poem”: Dis is di age af science an teknalagy / but some a wi a deal wid mitalagy / dis is di age af science an’ teknalagy / dis is di age af reality / but some a wi a deal wid mitalagy / dis is di age af science an’ teknalagy / but some a wi check fi antiquity.

I must turn to Wikipedia because I do not have the time or energy to write about this and related nonsense about morality: “The Moral Majority was a prominent American political organization associated with the Christian right and Republican Party. It was founded in 1979 by Baptist minister Jerry Falwell and associates, and dissolved in the late 1980s. It played a key role in the mobilization of conservative Christians as a political force and particularly in Republican presidential victories throughout the 1980s” →

The path to this conclusion begins with Frans de Waal’s Chimpanzee Politics: Power and Sex among Apes.

In his book The Rise of Christianity, sociologist Rodney Stark indeed links the expansion of Christianity in the Roman Empire with the success of the social services the community provided during devastating plagues: “The second (reason for the rise of Christianity) is to be found in an Easter letter by Dionysius, bishop of Alexandria. Christian values of love and charity had, from the beginning, been translated into norms of social service and community solidarity. When disasters struck, the Christians were better able to cope, and this resulted in substantially higher rates of survival. This meant that in the aftermath of each epidemic, Christians made up a larger percentage of the population even without new converts. Moreover, their noticeably better survival rate would have seemed a ‘miracle’ to Christians and pagans alive, and this ought to have influenced conversion.”

When I saw the first Star Wars movie in 1977 at the age of eight, I entered the theater a Christian but walked out an atheist. Before seeing the movie, I understood the war of good against evil to be an entirely Christian one: God vs. Satan. Imagine my shock when I saw on the screen a whole different order, a whole different war between the forces of good and the forces of evil—a war, furthermore, that made no mention of Jesus, or Lucifer, or the Last Supper. Yet, in the absence of any Christian codes of goodness, I still sided with that faraway galaxy’s own codes of goodness. As I walked out of the theater, I realized that God was limited, and what was infinite was the good itself, and that the good could take on many different shapes (Obi-Wan Kenobi, John the Baptist, Luke Skywalker, Jesus, Princess Leia, Mary).

What else is the first section of Spinoza’s Ethics but an effort to provide an anthropological account for morality? He wants to liberate God from human morality, recognizing how limited it is. What is good or bad according to us is not what is good or bad according to the universe. Indeed, the universe is cold to such anthropocentric values. The universe is just the universe.

It’s almost impossible for a human female to safely give birth without assistance, a fact that the sociobiolgist Sarah Hrdy places at the center of human sociality in her book Mothers and Others. According to this view, the absence of, say, extensive and moral elaboration in gorilla sociality, can be explained by the absence of helpers during the birth of a gorilla. Human sociality is bonded at and by this crucial moment, by the help that’s needed to birth and raise new humans. And why do human females need help? Because human bodies are weak and human babies have huge heads. As Jared Diamond points out in his short book Why Is Sex Fun: “A one-hundred-pound woman typically gives birth to a six-pound infant, while a female gorilla twice that size (two hundred pounds) gives birth to an infant only half as large (three pounds). As a result, human mothers often died in childbirth before the advent of modern medical care, and women are still attended at birth by helpers (obstetricians and nurses in modern first-world societies, midwives or older women in traditional societies), whereas female gorillas give birth unattended and have never been recorded as dying in childbirth.”

The work of cultural theorist Nancy Fraser and historian Linda Gordon convincingly shows that until the emergence of seventeenth-century European individualism, which also marked the emergence of modern capitalism, the concept of dependency was not negative. Among other things, it structured feudal society: the king depended on God, landlords on the king, peasants on landlords. With neoliberalism, the negative interpretation of dependency has gained ascendance.

Spinoza, Ethics, IVP18S.

My favorite passage in Georges Bataille’s The Accursed Share: An Essay on General Economy: “I will speak briefly about the most general conditions of life, dwelling on one crucially important fact: Solar energy is the source of life’s exuberant development. The origin and essence of our wealth are given in the radiation of the sun, which dispenses energy—wealth—without any return. The sun gives without ever receiving. Men were conscious of this long before astrophysics measured that ceaseless prodigality; they saw it ripen the harvests and they associated its splendor with the act of someone who gives.” This, in essence, is sun worship.

As Spinoza knew all too well, the God in the scriptures, the God who created the universe, was essentially human, the moral animal. But this misconception is to be expected. It’s as natural as the wind. “If a triangle could speak, it would say, in like manner, that God is eminently triangular, while a circle would say that the divine nature is eminently circular. Thus each would ascribe to God its own attributes, would assume itself to be like God.”