Military and cultural officials are not the only ones to blame for the intense scrutiny of artists and the deliberate acts of violence against them that erase them from state media and other systems of dissemination, legitimation, and history. Nor are the art critics and curators the only arbiters who evaluate or devalue, who elevate or bury artists’ work. Worst of all are the searing, inexcusable verdicts handed down by the artists themselves. They pit themselves against one another as they warily watch their competitors, always judging them and never tolerating their success (this idea was highlighted during the “Torneo Audiovisual” curated by Giselle Victoria for Aglutinador in 2010). But not all artists behave this way.

To be fair, I should point out that the arts sector is divided into a number of different groups: those who offer moral and conceptual support, those who engage in philanthropic projects (Artist x Artist at Carlos Garaicoa’s studio, PERRO and the Manic Art Museum by myself, and the Art Brut Project by Samuel Riera, among others) in order to support those who do not have the needed exposure and financial means to develop their own work. There are also those artists who have supported alternative events anonymously. And then there are those who dedicate themselves to their personal endeavor while maintaining the dignity and clarity needed to avoid speculating maliciously against their peers.

However, the ones who fear losing recognition (in the form of medals, prizes, exhibitions, grants, and so forth) or the profits earned and the connections made with official Cuban sectors are often the ones who assume the position of moral inquisitor in order to judge their colleagues. A recent example is the abuse and injustice committed against Tania Bruguera and her … Tatlin. This included criticisms and accusations—devoid of any evidence (as always, one has to believe in the emblematic verb)—media take downs, and a complete lack of internal support from her fellow Cuban artists (many of whom had supported her in the past). This is why I am reminded of the Biblical phrase, He that is without sin among you, let him first cast a stone (at her).

There are also those who seek to inject poison through destructive language or invasive texts; their brains being (of course) less than fully empowered. They weave their words together carefully and are willing, if need be, to lie in order to achieve their goals. There are also those apprehensive snipers who will attack on occasion while shielding themselves with pseudonyms as they engage in “cyber gossip,” poking at wounds and manipulating minds from the shadows. These are the ones who use their sadly celebrated opinions to wreak havoc, to exclude, and to impose sentences. At the same time, they vehemently demonstrate their absolute conviction that they have been “gifted” with “great wisdom” while appearing to be “humble missionaries of the hopeless.” However, they are in fact those who have simply failed to achieve the success they desired because of their own deficiencies or lack of self-management, and therefore, as they age they sift through dissimulation and wave after wave of malicious commentary to ruin the careers of their (preferably accomplished) colleagues, or they attempt by covert means to gain some sort of advantage by arrogantly undermining autonomous, persuasive, and altruistic projects of the sort that are presented at El Espacio Aglutinador. Of course, these snipers do not always hit their intended targets.

According to what I’ve been told by many people who have witnessed these comments and actions, it is clear that the content flowing from this latter group—the source, the motive, the phantom behind these hysterical tantrums—is based on nothing more than resentment, grudges, ingratitude, personal frustration, envy, and even gender discrimination. Thankfully, God did not grant this limited little group power or fame, common sense, a set of strategic skills, and—fortunately for humanity they lack an army equipped with the latest technology. It is no accident that this discovery has not been a negative one; in fact, it has been enriching for me. Thanks to these necrotic minds trying to sabotage Cuban culture, I’m learning to clear my slate and better appreciate the advantages that have been presented to me along the way. Many thoughts have come to mind, many ideas and summaries that have nourished and strengthened my current ideas and future projects as a creator and curator of events.

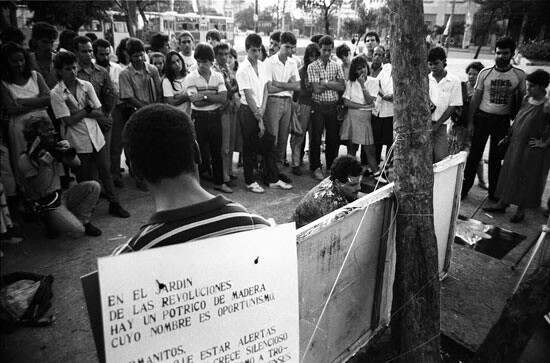

One of my future curatorial projects focuses on “El Proyecto G,” a 1988 endeavor whose great sin was to be closer to anarchy than orthodoxy. Despite its undeniably effervescent public success, it was a victim of these same sorts of archetypes we see today: it was undervalued by a group of “artists/theorists/scholars” who were the gatekeepers of the so-called institution of art itself. Those judges interacted directly with representatives of the Ministry of Culture and the National Council of Visual Arts, among other institutions of the Cuban revolutionary government. They ultimately determined who would emerge as the “good,” the “mediocre,” and the “poor” artists of that decade. They assumed they had the key to the truth, while I have to ask myself: Which truth? What sort of purely rational system of evaluation—impervious to the subconscious contaminants of vices both scholastic and traditional, personal interests, and emotional sensitivities, whether traumatic or not—can operate fairly with regards to art? (This notion was demonstrated at the event-competition held at Aglutinador, “Fuerte es el Morro, who I am?” in 2009 and the anarchistic “Curadores, Go Home!” in 2008.)

Now, some of these “pursuers of mediocrity” (that is, those who did not return with major depressive disorders) are, from their various locations in North America and Europe (where they spend part of their time), ferociously and radically criticizing the same officials and the same cultural systems of the Cuban government to which they belonged (and from which they benefited), and which operated (at the time) under their auspices, censoring, suppressing, and destroying Proyecto G, its creators, and others including the artist Ángel Delgado (who performed during the exhibition of “El objeto esculturado” in 1990), Arte Calle, and the Castillo project by Real Fuerza. Surprisingly, as time passed (that is, by the early 2000s), the 23 y G Skate Park became (and continues to be) the meeting point for groups of irreverent teens. In doing so they unwittingly give credit to the avant-garde movement from 1988, which established the location as a site of alternative cultural expression. The project’s energy and spirit remained, latent yet vibrant; its murmurings transcended dictatorial speeches, and musicians, poets, visual artists, craftspeople, emo kids, freaks, geeks, preppies, and punks would continue to gather, along with other, newly represented groups. Other voices also have the right to express themselves!

—Cuba, 2015

Subject

Dedicated to Proyecto G, Arte Calle, Aglutinator, Referencias Territoriales, Memorias de la post-guerra, Antonia Eíriz, Chago Armada, Ángel Delgado, Glexis Novoa, Tania Bruguera, and the other artists and projects who have been the victims of repression.

Translated by Ezra E. Fitz.