1.

The funniest moment of the only movie that Caetano Veloso ever made, O Cinema Falado (1986), is a scene in which Brazilian actress Regina Casé parodies the gestures and body language of Fidel Castro.1 Within the collage of an avant garde film-essay, the parody is a humorous parenthesis that alternates between quotes from Heidegger, Guimarães Rosa, Thomas Mann, Gertrude Stein, combining with popular dance and music scenes, the visual grammar of Cinema Novo, and an entire paraphernalia of juxtaposed monologues suggested, as Caetano once admitted, by Guillermo Cabrera Infante’s novel Three Trapped Tigers.

To show language as performance, and to take on topics such as politics, sexuality, art, and the avant-garde sensibility, are some of the intentions of the film, which was not as well received as its director expected. However, it is curious that in the film’s arsenal of connotations, there was a place reserved to parody the tropical Ubú, to demonstrate all the grotesque codes of his discourse, the performative essence of the caudillo.

This is something exceptional within the Latin American avant-garde world, which for a long time has venerated the symbolic capital of the Cuban Revolution.

2.

For decades, Fidel Castro’s image and attributes were taboo in Cuban art. Any type of parody was forbidden. Any allusion was severely censored or punished. Up to the late 1980s, no Cuban artist dared to take the most explicit image of power beyond propagandistic or official art.

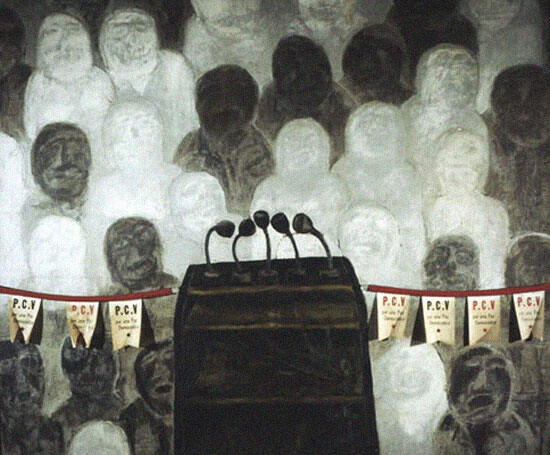

The symbols and messages of power were a space reserved for praise and propaganda. In 1968 at the National Painting Expo, when painter Antonia Éiriz dared to show her piece A Tribune for a Democratic Peace (an expressionistic vision of an empty podium with microphones among starkly grotesque faces) she received an almost immediate response from José Antonio Portuondo, who accused her of making art “not in agreement with revolutionary principles.” The effect of such words from one of the cultural commissars of the time was devastating: all around Éiriz a wall of silence arose, and one of our greatest painters was forced to leave her teaching position in 1969, and stopped painting for more than twenty years. In the end, she emigrated to Miami, where she died of a heart attack in 1995.

Toward the end of the 1980s, this situation began to change. Several artists (Arturo Cuenca, Carlos Cárdenas, José A. Toirac, Tomas Esson, René Francisco, Ponjuán, Pedro Álvarez, Juan Pablo Ballester) managed to overcome institutional resistance in order to gain access to the forbidden symbols and circumvent censorship. As Osvaldo Sánchez has explained so well, in what is called the “Generación de los Ochenta” (the 1980s Generation) the modernist ego competed with the dictating power of the state, and for a while exerted some type of civil authority that was not in opposition to an intense process of individualization.

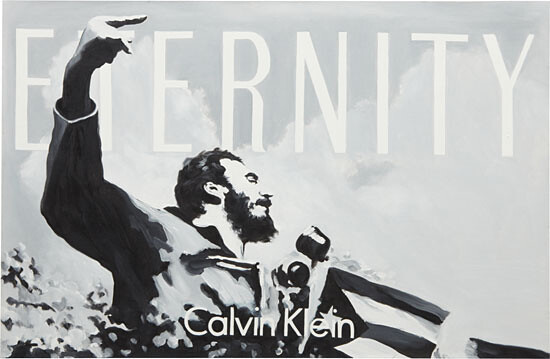

Many times, there existed a space of ambiguity, as with the jokes of Carlos Cárdenas or the ironic Parábolas (Parables) of José Angel Toirac, in which Fidel Castro’s image nonchalantly advertises Cannon or some Cuban cigars (images that were ironic as well as prophetic: later, Fidel’s likeness would be used to advertise everything from beer, to a sales website, and even to a steakhouse).2 The ultimate extreme of this ludic ambiguity has been well explained by Gerardo Mosquera when he talks about Aisar Jalil Martínez, whose physical resemblance to Fidel Castro allowed him to paint irreverent self-portraits full of double entendre that no one, including art critics, had the audacity to point out, so as not to be accused of projecting their own “politicized” vision. This is evasion as a trope.

Then came exile: a way of freeing the discourses and old fears. By 2007, when Glexis Novoa introduced a Fidel Castro body double in the show ‟Killing Time” (Exit Art, New York) and unfolds his performance Honorary Guest, the space for ambiguity was minimal.3 What prevailed were mockery and grotesque. The avant-garde has demonstrated again that Ubú can serve as readily available and significant material for art. The exorcism had been consummated.

3.

If in the 1980s the other side of the conversation was the state through its institutions and intermediaries, in the succeeding generation—the one that Sánchez has called “Generación Jinetera”4 (a name that has shown itself to be extremely true and visionary), and that Gerardo Mosquera has called “the noxious weed” (for its capacity to thrive in unfavorable conditions)—what mattered was to talk to the market beyond Cuba’s borders. Legitimacy is now somewhere else; the “Special Period” has also devastated the value of the work. To gain legitimacy one has to assimilate in a postmodern fashion, recycling topics from the 1980s, diluting the modern project into inane eclecticism. From irony and satire, we move to cynicism.

Now that that market allies itself again with the state, it begins to reproduce a much more dangerous and powerful kind of censorship than that which people tried to circumvent in the 1980s. When the digital newsletter Cuban Arts News—a project of the investor, collector, and mogul Samuel L. Farber—reproduces the police logic of Cuba’s Ministry of Culture and avoids mentioning the thwarted performance of Tania Bruguera at Revolution Square (El Susurro de Tatlin [Tatlin’s Whisper]), or when Art on Cuba magazine, conceived for American tourists to the island, skips the most controversial topics of Cuban artistic discourse, there is an alliance between the interests of the market and the criteria of political adequacy that were challenged in the 1980s.

Speaking of the “Tania Bruguera affair,” it is also alarming to see famous artists, intellectuals, even representatives of the previously nonconforming generation, assuming as their own, or even giving argumentative value to, the logic of the political police (“Well, she had been warned, she knew what was going to happen to her”—a response that is one step away from the corollary that justifies not speaking out in support of someone censored and violated: “She asked for it”). As if this was not the very definition of an aesthetics and philosophy of doing (Bakhtin). Of course Tania knew, just as Antonia Eiriz knew in 1968, and just as the Generación de los Ochenta artists knew. It is important, both in art and in life, to defend the right of the artist to question political power and challenge censorship.

That someone like Luis Camnitzer could say that Bruguera’s situation, detained in Cuba, is not so bad since she can still visit graffiti artist Danilo Maldonado at the Valle Grande prison, makes one harbor dark ideas of possible conceptual actions, like leaving Camnitzer without a lawyer and without a passport in some other country with a judicial and police system similar to Cuba’s.5 Neither can one understand the praise from the cultural establishment for the “great cultural role of the Havana Biennial” after the piece by Yeny Casanueva and Alejandro González in which they exposed the state security service’s surveillance of several cultural personalities and institutions that attended the ninth Biennial in 2006. The Biennial is also part of that terrible confusion of arts and tourism that the 1980s artists mocked so much.

Very few Cuban artists of the Generación Jinetera will not show solidarity toward an artist targeted by the state security services, since this would not only mean repression and ideological ostracism, but also market restrictions; they are unwilling to jeopardize access to collectors, tourist visits to their studios, the privileges granted by the state to their artistic and real estate projects, their permission to travel, and their financial rewards. A malignant fusion of communist and capitalist instruments of power dominate the “postideological” space that Cuba has supposedly become since December 17, 2014.

Bruguera’s podium at Revolution Square remained empty, although for reasons different from what Eiriz’s images showed at the end of the 1960s. Around that podium there has been a very loud silence that speaks volumes about the machinery of police and institutional control that should not continue to rule the destiny of Cuban art.

4.

When artist Nelson Domínguez opens a show of drawings of Fidel Castro and hastens to add, “to draw Fidel is to draw history … is to draw Beauty,” or when Raúl Castro gifts the Pope a painting by Kcho that shows a cross made of boats and a young boy praying before it, one is forced to think of a time prior to the 1980s when the strategies of dissent and irreverence were legitimizing elements.

Many political experts and art critics like to use the term “post-Castroism” to describe this latest phase of Cuban nihilism. But it is a post-Castroism without a death certificate or artistic legitimacy.

Two things come together in this corpse that refuses to let itself be seen and judged: the people’s political destitution, and the taboo around death. Perhaps corpses are not things of the people, but they can be things of artists. Or at least they have been for centuries. The corpse allows the artist to rescue a time undone, and at the same time mock death. In other words: the more an artist fills him/herself with death, the more he/she transcends it. Let us remember Goya drawing among the piles of shooting-squad victims at La Moncloa, Rembrandt attending autopsies to create his two anatomy paintings, David before a freshly stabbed Marat, or Caravaggio turning a dead woman fished from the Tiber River into the Dead Mother of God; or Grünewald, of course.

The Cuban people need to overcome the death taboo and face Fidel Castro’s corpse—while also preparing themselves to bury his political legacy. To own this collective need to visualize a corpse could become a revitalizing imperative for Cuban art.

After the Revolution, several Cuban artists lingered over José Martí’s corpse. There are notable results of this, like the agonizing Apóstol by Elso. A good portion of our Pop art took abundant advantage of the sublimated image of Che, an icon that could never have been “processed” during the guerrilla fighter’s lifetime. And there are the 1980s, which show the best of our demystifying instinct. But none of the three currently coexisting generations of artists dares to paint the corpse of the Commander in Chief.

Only a marginal artist, Danilo Maldonado (aka El Sexto), has offered evidence of that mocking spirit with a thwarted piece that is, nevertheless, much more creative than the praiseful tropes of the official artists.

To free two greased-up pigs carrying the names of Fidel and Raúl in Havana’s Central Park is not only an action full of blaspheming humor, but also a project that gathers together a group demystifying connotations that already seem like part of a forgotten archive.6 One can only imagine the spectacle of that kermesse, with citizens running after the elusive swine (a symbolic animal in Cuban culture, signifying both salvation from hunger and a scapegoat), or the dilemma of giving political significance to the national ritual of sacrificing pigs.

Category

Subject

Translated by Ernesto A. Suarez