One of comedian George Carlin’s (1937–2008) seminal monologues was his 1986 riff on stuff: “That’s all the meaning of life is: trying to find a place to put your stuff. That’s all your house is, is a pile of stuff with a cover on it.” And to paraphrase: “Someone else’s stuff is actually shit, whereas your own shit isn’t shit at all, it’s stuff.” I’m made aware of this every time family members visit my house and see the art I collect. I see those very words etched onto their retinas, and I can imagine the conversations they’re having in the car driving away: “Do you think maybe all that art stuff he collects is a cry for help?”

“That art stuff of his? It’s not stuff; it’s shit.”

“But it’s art shit. I think it might be worth something. It’s the art world. They have no rules. They can turn a piece of air into a million dollars if they want to.”

“So, maybe it’s not shit after all.”

“Nah. Let’s not get too cosmic. It’s shit. Art shit.”

Ahhh, families.

* * *

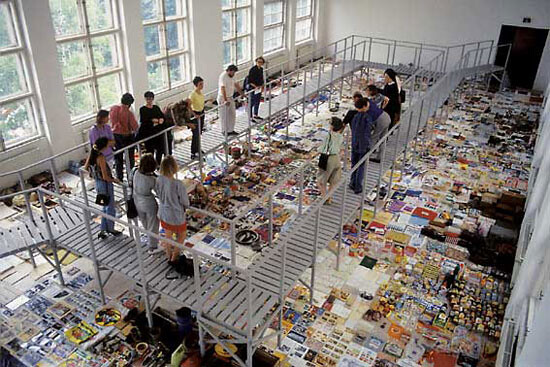

In April I wrote about links between hoarding and collecting in the FT Weekend magazine. The piece recoded art collecting and art fair behavior as possibly being subdued forms of hoarding. Basically: Where does collecting end and hoarding begin? One thing the piece didn’t ask was: What are the clinical roots of obsessive hoarding? (Which is now a recognized condition in the DSM-5.) One thing psychologists agree on is that hoarding is grounded in deep loss. First there needs to be a preexisting hoarding proclivity (not uncommon with our hunter-gatherer heritage.) If someone with a proclivity experiences a quick and catastrophic loss—often the death of a close relative, frequently in car accidents—one need wait approximately eighteen to twenty-four months before hoarding kicks in. Reality TV shows on hoarding (A&E’s Hoarders; TLC’s Hoarding: Buried Alive) would have us believe that given dozens of helpers and a trained therapist, hoarders are often cured by the end of the TV episode. The truth, though, is that there’s really no cure for hoarding. Once it’s there, it’s pretty much there to stay.

On these same TV shows, a voiceover regularly tells us that hoarding behavior is unsanitary and unsafe. This is correct. A few years back, a family friend—a big-game taxidermist who ended up making more money renting out mounted animals to TV and film shoots than he did with his trade—was killed in an electrical fire that began in his basement. He ran into his basement trying to put it out, got trapped, and quickly died of smoke inhalation. His retail storefront had always been immensely dense with hides, heads, and antlers. Nobody was surprised to learn his house had been equally as dense, but it was odd to think of his pack-ratting as being possibly medical.

One of the borderline ghoulish (and best) parts of watching TV shows about hoarding is seeing the expressions on the faces of hoarders once they realize that the intervention is for real. Your relatives are everywhere poking out from behind mounds of pizza boxes and mildewed second-hand Raggedy Ann dolls. There’s a huge empty blue skiff in the driveway waiting to feast on all of your stuff, and it’s surrounded by a dozen gym-toned refuse movers. There’s a blond woman who looks like J. K. Rowling (1965– ) asking you how you feel about an oil-stained Velveeta box you ate on the morning the Challenger exploded.

This is actually happening to me—everyone is watching me.

Until then it’s usually quite friendly, and in some cases hours can pass, and some deaccessioning progress is made, but then comes something—usually something utterly useless (Jif peanut butter jar, circa 1988, contents used but jar not cleaned or rinsed) and the hoarder chokes—it’s in the eyes: a) I may need that jar at some point down the road, and b) This intervention is over. From there it’s only a matter of how much of a meltdown it’s going to be, and how ornery the hoarder needs to be to eject everyone from his or her house.

Needless to say, one feels a tingle of superiority knowing that one would never ever have one’s inner life come to a grinding halt over throwing out a twenty-seven-year-old unrinsed jar of peanut butter. But if it wasn’t that jar of Jif, what would it be that made someone—you—choke? Losing the nineteenth-century rocking chair? That small David Salle (1952–) canvas? And wait—how did a jar of Jif ever become the shorthand for life and its losses? Is that what the Brillo boxes were all about? How does a Christie’s evening postwar contemporary art sale become a magic-wanding spectacle where, instead of peanut butter jars, bits of wood and paint are converted from shit into stuff? How do objects triumph and become surrogates for life?

* * *

I think it was Bruno Bischofberger (1940– ) who said that the problem with the way Andy Warhol (1928–1987) collected art was that he always went for lots of medium-good stuff instead of getting the one or two truly good works. Warhol (the hoarder’s hoarder) would probably have agreed, but I doubt this insight would have affected his accumulation strategies.

A publisher I worked with in the 1990s has a living room wall twelve-deep with Gerhard Richter (1932– ) canvases. God knows how many he has now, but however many it is, it will never be enough.

A few years back I visited a friend of a friend in Portland with a pretty amazing collection of post-1960 American work. He went to the kitchen, and when he came back he saw me staring into the center of a really good crushed John Chamberlain (1927–2011).

“What are you staring at?”

“The dust.”

“What do you mean?”

“Inside this piece, there’s no dust on the outside bits, but it’s really thick in the middle.”

He looked. “I think that’s as far in as the housekeeper’s arms can reach.”

“Your housekeeper Windexes your art?”

I saw his face collapse. Thousands of dollars later I believe the piece was professionally cleaned with carbon tetrachloride dry-cleaning solution at immense cost. It reminded me of reading about Leo Castelli (1907–1999), who wasn’t allowed to have regular housekeeping staff in his apartment. In order to keep his insurance he had to have MFA students work as his housekeepers. I wonder if they’re now making MFA Roombas.

* * *

I think it’s perhaps also important to note that most curators almost never collect anything—yes, all those magazine spreads with the large empty white apartments—and if you ever ask a minimalist curator what they collect, they often make that pained face which is actually quite similar to the Jif jar lover upon the moment of possible surrender. But you don’t understand, I have no choice in this matter. You merely see an empty apartment, but for me this apartment is full of nothingness. That’s correct: I hoard space. A friend of mine is a manufacturer and seller of modernist furniture. Five years ago he built a new showroom, and he was so in love with how empty it was, he kept it unused for a year as a private meditation space.

Most writers I’ve met, especially during the embryonic phase of writing a novel, stop reading other writers’ books because it’s so easy for someone else’s style to osmotically leak into your own. I wonder if that’s why curators are so often minimalists: there’s nothing to leak into their brains and sway their point of view, which is perhaps how they maintain a supernatural power to be part of the process that turns air into millions of dollars.

On the other hand, most art dealers are deeply into all forms of collecting, as if our world is just a perpetual Wild West of shopping. I once visited a collector specializing in nineteenth-century North American West Coast works who had an almost parodically dull house in a suburb at what he called “street level.” But beneath this boring tract home were, at the very least, thousands of works arranged as though in a natural history museum.

Designer Jonathan Adler (1966– ) says your house should be an antidepressant. I agree. And so does the art world. When a curator comes home and finds nothingness, they get a minimalist high. When a dealer comes home and finds five Ellsworth Kellys leaning against a wall, they’re also high in much the same way. Wikipedia tells us that “hoarding behavior is often severe because hoarders do not recognize it as a problem. It is much harder for behavioral therapy to successfully treat compulsive hoarders with poor insight about the disorder.” Art collectors, on the other hand, are seen as admirable and sexy. There’s little chance of them seeing themselves as in need of an intervention. Perhaps the art collecting equivalent of voluntarily getting rid of the Jif jar is flipping a few works.

* * *

I have a friend named Larry who collects beer cans, but his wife has a dictum: no beer cans may cross the doorsill of his collecting room. Larry then made a beer can holder that attaches itself to any surface, ceilings included. He then patented his holder and started selling them commercially. His is a capitalism feel-good story which highlights another dark side of hoarding and collecting: our failures and successes in regards to how we accumulate things are viewed almost entirely through a capitalist lens. How much did you get for it? I’m uncertain what Marx said about art collectors (if anything), but it probably wasn’t kind. Some people collect art that’s purely political, or purely conflict-based, or highly pedigreed by theory, but I wonder if they’re just trying to sidestep out of the spotlight of the art economy’s vulgarity. But wait—did they magically win their collection in a card game? Did their collection arrive for free at their doorstep from Santa Claus? No, it had to be purchased with money, and it’s at this level where the dance between academia, museums, and collectors turns into a beyond-awkward junior high school prom. I tried explaining a Tom Friedman (1965– ) work to my brother. Its title is A Curse, and the work consists of a plinth over which a witch has placed a curse. I told my brother it might easily be worth a million dollars, whereupon his eyes became the collective eyes of the Paris Commune, aching to sharpen the guillotine’s blades and then invade, conquer, and slay Frieze.

* * *

The collecting of stuff—slightly out-of-the-ordinary stuff—is different now than it was in the twentieth century. eBay, Craigslist, and Etsy have gutted thrift and antique stores across North America of all their good stuff, and in Paris, the Marché aux Puces de Saint-Ouen is but a shadow of its former self. eBay itself, once groaning with low-hanging fruit being sold by the clueless, is now a suburban shopping center with the occasional semi-okay vintage thingy still floating around. This same sense of sparseness is felt in the museum world, where the slashing of programming budgets remains the norm. In addition, too much globalized money and not enough places to stash it has made pretty much anything that is genuinely good far too pricey for the 99 percent. The good stuff is always gone, and all the stuff that’s left is shit. You don’t stand a chance against moneyed, technologically advanced collectors who have some magic software that allows them to buy that Jean Prouvé stool three-millionths of a second ahead of you. Thank you, internet.

On YouTube, you’ll find anti-hoarding videos that coach overcollectors to get rid of any object that doesn’t bring them joy. But perhaps this is contrary to human nature. In Australia last month I asked if I could visit that secret stone alcove where the last three remaining specimens of the world’s rarest tree are kept hidden.

“Why would you want to do that?”

“I want to get one before someone else gets it.”

That’s human collecting behavior.

* * *

I sometimes wonder if there’s a way to collect stuff without tapping into collecting’s dark, hoardy side. I got to thinking that if visual art is largely about space, then writing is largely about time—so then maybe people collect books differently than they do art.

Do they?

No, they don’t. Book hoarding tends to be just as intense as art hoarding, if not worse. It’s called “bibliomania,” and like generic hoarding, it is a recognized psychological problem. Enter Wikipedia once again: “Bibliomania is a disorder involving the collecting or hoarding of books to the point where social relations or health are damaged. It is one of several psychological disorders associated with books, such as ‘bibliophagy’ (book eating) or ‘bibliokleptomania’ (book thievery.)”

Bibliomania, though, is almost universally viewed as quirky and cute, the way “kunstmania” (my coinage) is seen as glamorous and cool in a Bond villain kind of way. Oh those booksellers sure are nutty! And they are nutty—pretty much all bookstore owners recognize that the profession brings with it a unique form of squirreliness. The best booksellers, the antiquarian sellers especially, are those sellers who genuinely don’t actually want to sell you the book. You have to audition for its ownership, and should they sell you the book, you can see the pain on their face as the cash machine bleeps.

I once worked weekends in a bookstore. There was this guy who’d been coming in for years and all the other sellers made cooing noises whenever he showed up for three hours every Sunday for some passionate browsing. “Now there’s someone who really loves books—a real book lover.” And then one Sunday afternoon a New York Times Atlas fell out of his raincoat as he was exiting the store. Police later found thousands of stolen books in this bibliokleptomaniac’s apartment.

As for bibliophagy, I chuckled when I learned of the term while writing this and then was chilled when I realized I’m a bibliophagist myself …

* * *

Back in the early 2000s, my then agent, Eric in New York, was one of the first people I knew to overharvest music into an iTunes playlist. In 2002 it seemed amazing that a person could have 1.92 days (!) of music on their playlist. These days it’s not uncommon to find people with almost a solid year’s worth of playlisted music, if not far more.

In high school everybody used plastic Dairyland milk crates to store their records. They were just the right size for 33 1/3 LPs, and Dairyland was able to have their logo inside everyone’s house in the most wonderful way—attached to the music loved by the owner. And then Dairyland changed the dimensions of the crates so that they’d no longer hold vinyl. I’m still mad at them, not because I wanted crates for myself (I’ve never been a big vinyl aficionado), but rather because they took such a major plus and turned it into a big minus. Idiots. Vinyl collectors are among the most reverent of all collecting communities. Those milk crates would have lasted peoples’ entire lives.

Music is weird because it’s not really space, but it’s not quite time either. This got me thinking that okay, yes, visual art is mostly about space, whereas writing is largely about time. But what would a hybrid time/space creative form be? The answer is: film. Do people hoard film? Actually, they do. My sister-in-law’s cousin is a movie hoarder who has possibly millions of hours of torrented movies snoozing on his hard drives, movies he could never watch in ten lifetimes. “Don, let me get this straight: You speak no German and yet you have five German-language screening versions of Sister Act Two starring Whoopi Goldberg (1955– )?”

“Yes. Yes, I do.”

I think the human relationship with time perception has altered quite a bit since 2000, and film seems to be one venue where this is fully evidenced. The internet has a tendency to shred attention spans while it fire-hoses insane amounts of film on humanity, making film hoarding as easy as newspaper hoarding was back in the 1950s. Even easier.

In the art world, our collectively morphing sense of time perception became truly noticeable back in 2010 with The Clock by Christian Marclay (1955– ), which in many peoples’ minds deserved the Best Picture Oscar for that year. At the 2015 Oscars, the only two real contenders for Best Picture were Boyhood by Richard Linklater (1960– ) and Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance) by Alejandro González Iñárritu (1963–). In both films the star was, as Linklater put it, time. In Boyhood we saw the magic of a dozen years of continuous time. In Birdman we saw the magic of one continuous take. As a species we seem to have now fetishized continuity. We’re nostalgic for real time’s flow, and we hoard movies and videos and GIFs and clips and anything else that moves and has sound, knowing it’s never ever going to be touched. In a weird way, it’s like the minimalist apartment of, say, curator Klaus Biesenbach (1967– ), where no objects are visible, and what is present is virtual—in the case of Biesenbach, ideas; in the case of my sister-in-law’s cousin Don, twenty-nine million hours of crap film.

In Men in Black, Tommy Lee Jones (1944– ) learns of an alien technology and says, “Great. Now I’m going to have to buy The White Album again.” In my case, it’s Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, which I’ve now bought twice on vinyl, once on cassette, once on CD, and twice on iTunes. There’s surely some geek in California dreaming up some new way of making me buy it all over again. By now don’t I get some kind of metadata tag attached to me saying, “This guy’s already paid his dues on this one”?

* * *

Other than actually dying, there is one thing that genuinely stops hoarding: the thanatophobia one feels at the thought of death approaching. One is forced to contemplate what will be written on one’s gravestone:

born

accumulated a bunch of cool stuff

died

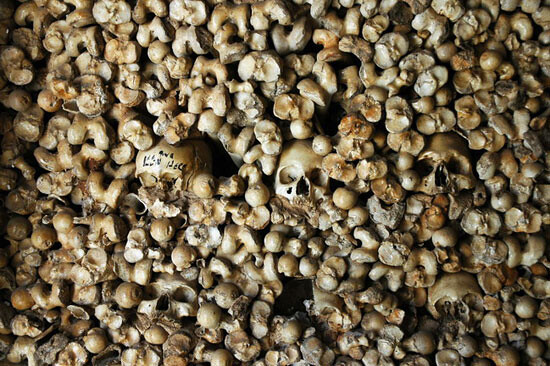

This epitaph isn’t creepy, it’s just boring. So how do you manipulate your loot meaningfully while the clock ticks and ticks and ticks? With artists, dealing with stuff at the end of life becomes complicated. I find it interesting that, say, Constantin Brâncuşi (1876–1957) didn’t want to sell his work in his final years. He could afford not to, and he wanted to be surrounded by his own stuff. He wanted to live inside it, and it’s no coincidence that when he died he wanted his studio kept frozen in time at that moment. Reece Mews, the studio of Francis Bacon (1909–1992), with its tens of thousands of paint tubes, was the world’s most glamorous toxic heavy metals waste dump. And one can’t help but wonder about Andy Warhol, with his townhouse stuffed with unopened bags of candy, cookie jars, jewels, and Duane Reade concealer. Did he ever open up the doors of the rooms in his townhouse once they were full? Did he stop and stare at the doors, shiver, and then walk away?

In December of 2013 I saw a magnificent show at Stockholm’s Moderna Museet, “Turner, Monet Twombly: Later Paintings.” It featured works done in the final decade of the lives of John Turner (1873–1938), Claude Monet (1840–1926), and Cy Twombly (1928–2011). To quote the museum’s website, the show focused on these artists’ “later work, examining not only the art historical links and affinities between them, but also the common characteristics of and motivations underlying their late style.”

The paintings in the show were remarkable in and of themselves, yet what they collectively foregrounded was a sense of whiteness, a sense of glowing—an undeniable sense of the light that comes at the end of the tunnel. Overt content became less important, and the act of cognitive disassociation from the everyday world was palpable. As the museum catalog further states, “Their late work has a looseness and an intensity that comes from the confidence of age, when notions of finish and completion are modified.” A delicate way of phrasing things.

The works at the Museet depicted, in their way, anti-hoarding—a surrendering of life’s material trappings. It was a liberating show that gave the viewer peace. It let you know that maybe you should let go of many things in your life before its nearly over, when suddenly your stuff isn’t as important as it was cracked up to be. (If you ask anyone over fifty what they’d rather have more of, time or money, they’ll almost always say time.)

An obvious question here at the end: Is it that art supercollectors, as well as bibliomaniacs, have experienced losses of a scope so great that they defy processing? Are these collectors merely sublimating misfiring grief via overcollecting? A reasonable enough question, but why limit it to collecting art or books? People collect anything and everything. And look at Darwin. Back in the days of caves, if someone close to you died or got killed, chances are your life was going to be much more difficult for the foreseeable future, so you’d better start gathering as many roots and berries as you can. Collecting as a response to sudden loss makes total sense. But also back then, if you somehow lived to thirty-five, you were the grand old man or dame of the cave, with very little time left on the clock. Divvying up your arrowheads and pelts made a lot of sense—and you best do it before your cave mate descendants plop you onto an iceberg and send you out into the floes.

I get the impression that collecting and hoarding seem to be about the loss of others, while philanthropy and deaccessioning are more about the impending loss of self. (Whoever dies with the most toys actually loses.)

Maybe collecting isn’t a sickness, and maybe hoarding is actually a valid impulse that, when viewed differently, might be fixable through redirection tactics. Humanity must be doing something right, because we’re still here—which means there’s obviously a sensible way to collect berries and roots; there’s probably also a sensible way to collect art and books (and owl figurines and unicycles and dildos and Beanie Babies and … ) The people who freak me out the most are the people who don’t collect anything at all. Huh? I don’t mean minimalists. I mean people who simply don’t collect anything. You go to their houses or apartments and they have furniture and so forth but there’s nothing visible in aggregate: no bookshelves, no wall of framed family photos … there’s just one of everything. It’s shocking.

“You mean you don’t collect anything?”

“No.”

“There must be something. Sugar packets? Hotel soaps? Fridge magnets? Pipe cleaners?”

“No.”

“… Internet porn? Kitten videos?”

“No.”

“What the hell is wrong with you!”

“What do you mean?”

“If this was ten thousand years ago and we all lived in a cave, you’d be an absolutely terrible cave mate. You’d be useless at foraging for roots and berries, and if you went hunting you’d only have one arrowhead, so if you lost it, you’d starve.”

“Where is this coming from, Doug?”

“Forget it. Let’s go gallery hopping right now.”