The world’s population is to increase by between 1.5 and 2.5 billion by 2050. In the coming two decades “more than seven hundred million households will be added,” according to Tobias Just, professor of real estate management at the University of Regensburg. “But because urbanization is advancing rapidly,” adds Just, “especially in Africa and Asia, and the relocation of a household from the countryside to the city creates an additional need for housing, about a billion more dwellings need to be completed by 2030 to meet demand.”1

It is clear from the numbers alone that the form of future residential buildings can no longer be addressed by means of conventional architecture. The question then becomes: What form will these dwellings take?

Most occupants of these new structures will not have the money to finance a house as we generally know it, or even an apartment in a high-rise. According to UN Habitat, 400 million city dwellers already live in critically overcrowded accommodations, especially in South Asia and India, where over a third of the urban population lives in spaces occupied by more than three people. In New York, as of this writing, twenty-two thousand children live on the street—the highest number since the Great Depression of the 1930s. Seventy-two percent of the population of sub-Saharan Africa lives in slums; in Southeast Asia the number is 59 percent.2 Both economically and ecologically, it will be impossible to meet housing demand with the traditional methods and forms of architecture and urbanism.

The problem is exacerbated by the adoption of Western forms of urban sprawl in Asia. Traffic jams in major Chinese cities have taken on apocalyptic dimensions, even though population density in large cities in China and India is still relatively low. According to statistics compiled by the German Federal Agency for Civic Education, only 3 percent of the urban population of China lives in Shanghai, whereas 42 percent of the Japanese urban population lives in the metropolitan area of Tokyo.3 It is not difficult to imagine what will happen if Chinese metropolises catch up with Japan in terms of traffic and population density. If only because of dwindling resources, the European and American model of domestic architecture and “social housing” has come to an end. The issue then is how to provide residents, within the smallest area and for as little money as possible, space for privacy, shelter, and the exchange of information, as well as communal spaces that transcend familiar building typologies—and how to convert and repopulate buildings (estates, factories, administration buildings) that have been abandoned in huge numbers in thinned-out peripheries and areas beset by population loss.

The Case of Argentina

According to UN Habitat, in the next two decades over 30 percent of all urban residents will likely to live in slums. A society that still stands by the idea of living in dignified and safe conditions must begin here, in the political and architectural dimension; working conditions must be defined according to an income that supports a dignified life. According to statistics from the NGO A Roof for My Country (UTPMP), half a million people around Buenos Aires live in slums, of which more than half were built on public land—half of them under or next to motorways or near landfills.4 About 80 percent have no sewage treatment or gas supply. There are primary schools but no secondary schools in these neighborhoods, which contributes to the low standard of education; social advancement is virtually impossible, or possible only through illegal means.

In Brazil, favelas have by now become barely distinguishable from growing neighborhoods. Heliópolis, in southeast São Paulo, was originally a favela in the 1970s. Today, over one hundred thousand people live there; the muddy slopes have been paved and are now official streets. The favela Rio das Pedras in eastern Rio de Janeiro has developed into a city center. Even in the slums, gentrification occurs: houses are built, shops spring up, and the poorest of the poor are pushed to the edges of the slums, where they live in makeshift shelters. The subdivisions of settlements that develop on the edges and in the middle of metropolises, as a result of either illegal slum building or official urban planning, no longer work; Villa 24 in Buenos Aires, for example, is a slum whose streets don’t show up on any map, but whose infrastructure is organized better than many official social housing projects, such as the Barrio Soldati neighborhood, completed in 1978.

In the 1940s, railway workers and migrant workers from South American countries initially settled in Villa 24. Under a “Plan de Erradicación de Villas de Emergencia,” the right-wing government attempted to force the inhabitants to either enter regulated social housing away from the city, or leave the country all together. The plan failed; today, some forty-five thousand people live in the Villas 21 to 24. At the same time, since 2001 the population of the slum district Villa 31, near the upscale residential neighborhood of Retiro, has more than doubled.

There were attempts to evacuate this neighborhood under the military dictatorship. In 1974, Carlos Mugica, a local priest and social worker, was assassinated by right-wing anti-communist paramilitaries. Still, with rental costs increasing across the city, the neighborhood grew rapidly beginning in the mid-1980s. Since the 2007 inauguration of conservative mayor Mauricio Macri, the city government of Buenos Aires has tried to force the relocation of the entire slum to the outskirts of Buenos Aires. The national government, however, established a plan to convert the informal settlement into a legal district.

Improving living standards in such neighborhoods is mainly a matter of infrastructure: sewage systems and schools can be built and landfills can be relocated. Policy that deals with what is casually referred to among architects as “slum upgrading” (as if slum dwellers were airline passengers who can get upgraded from “homeless” to “living in a tin shack with no toilet”) cannot confine itself to donating a fountain here and a bit of asphalt there; it must develop plans that go further than slight improvements to the existing self-constructed infrastructure. Architects must commit not just to creating sculptural building objects within this system, but to constructing social statuaries.

A77: A Revision of the Image of the Architect in Argentina

What could a building that goes beyond superficial “slum upgrading” look like? The Argentinian architects Gustavo Dieguez and Lucas Gilardi, who operate the architecture firm A77, define their role as architects differently. They often attend to their building—mostly through infrastructural interventions—over long periods of time. They always return to the building process to discuss improvements with the dwellers before rebuilding or adding to the structures. On the Plaza Parque Patricios they built their wooden structure El gran Aula, which was composed of modules and embodied the idea of an “open school.”5 Each module was used to teach something: photography, design, music, cooking. In the case of El gran Aula, the building isn’t a formally defined sculpture, but rather an open framework for various forms of action, occupation, and implantation.

In 2007 the young Ecuadorian architects Pascual Gangotena and David Barragán founded their office Al Borde, geared towards passing on architectural know-how to the poor who can’t afford architects, thereby contributing to a no-budget culture of building. Their projects pursue infrastructural innovation and operate on open-platform principles that encourage the free dissemination of complex structural knowledge.

In the 1970s, a multilevel concrete block was erected in São Paulo, but never completed. The concrete skeleton stood empty until the 1980s, when homeless families occupied the building, setting up self-constructed sanitary systems and open power lines. Despite this precarious housing situation, the building was popular, as there were plenty of job opportunities, schools, and other social institutions nearby. Beginning in 2002, students in the architecture department at the University of São Paulo, together with the seventy-three families that lived in the building, cleaned up the site, installed a communal power grid, and painted the façade; the words “Edificio Uniao” (Union Building) were painted on the facade to give the building a personality.6 Gates were installed at the entrances to the small alley in front of the building, turning it into an elongated courtyard were children could play safely. Further measures included rebuilding the flat roof into a shared roof terrace and turning the dreary entrance into a dignified foyer where people could sit together with visitors—a kind of public living room for the building.

While a few interventions have changed the site’s character for the better, in certain respects the social housing mistakes of the 1970s are being repeated: growing structures are demolished and replaced by visions from the drawing board. The result is a diminished quality of life—in the open spaces that serve both as playgrounds and as meeting spaces, and in the narrow streets where people meet. Everything that was afforded by the fragmentation of the favela is being abolished. The residents are being robbed of the last form of capital they have: their proximity to one another.

Staying On-Site: A New Role for the Architect

It is possible for planners to reimagine the chaotic, informal city in better terms. A model for this was developed at ETH Zurich under Marc Angélil. In one seminar, students proposed plans to expand a favela by creating empty concrete frames with built-in water and power supplies, which could be occupied by the inhabitants in agreement with the city, and which could be expanded according to the inhabitants’ needs.7 This was essentially a radicalized version of Alejandro Aravena’s Quinta Monroy housing project in Iquique, Chile, where the inhabitants are able to expand their own buildings.

In Christian Esteban’s far-reaching conceptual designs, living spaces facing the street can become shops, communal kitchens, or start-up offices. His constructions can accommodate the stacking of additional layers when housing is needed. This kind of open urbanism only works if other conditions are established. For example, small business owners need to receive microcredit for their start-ups so the land won’t fall victim to real estate speculation. This kind of state governance has nothing to do with the welfare state paternalism some liberals complain about. It is rather a sensible investment, not only economically, but also ethically and socially. Transforming favelas into thriving microeconomies can help avoid the enormous social costs that accompany urban decay and widespread impoverishment.

Underlying both of these approaches is an entirely different conception of living. An open framework is established which gets filled in over the years—rebuilt, redefined, and transformed without any control on the part of the architects. This concept was originally pioneered by Bernard Rudofsky in his legendary 1964 book Architecture Without Architects, and by Giancarlo de Carlo in his 1970 essay “Architecture’s Public.” Residents were once the inmates of concepts devised elsewhere, but here, by contrast, residents are stakeholders, remodelers, and active co-creators of neighborhoods and cities. This redefinition also applies to the architect’s role. The architect becomes the initiator of social processes, but not necessarily on the side of power and capital; then the architect repeatedly returns to the setting of his or her construction to adjust it to its surrounding metamorphoses.

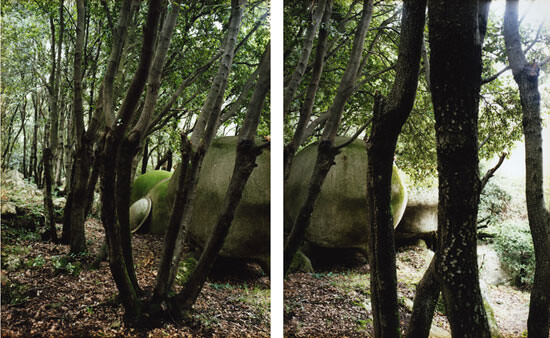

The Hungarian-French architect Antti Lovag, who passed away in 2015 at the age of 94, was a radical utopian pioneer of this definition of the architect: someone who lives on site as a figure intertwined with the life of his buildings. He built an experimental commune in Tourrettes-sur-Loup near Nice and Cannes and, from 1968, lived there with up to fifty people, who together worked on a 1600-square-meter biosphere until 1982.8 No architectural plans were drawn up for the biosphere. Instead, the commune’s small team worked according to the principles of trial and error, developing systems in which small housing spheres could be aligned and could traverse large areas. It was building without design method or architecture, more Tekton than Archein—a more playful and purposeless Hodos, or “way.” The construction was built around a central spherical hall through which a stream trickled over real rocks, and in which a jungle of cacti and palm trees grew. This space was surrounded by countless intimate spherical rooms lit by the sun. Depending on a user’s needs, the entire complex could continue growing. Lovag was given the contract to build this four-hundred-meter-long utopian sphere in 1967 by a man named Antoine Gaudet, a powerful figure in the Parisian stock market. Lovag was already in his late forties and had led a life rich enough to serve as the basis of a great adventure novel.

Born in 1920 to a Jewish engineer who built movie theaters, Lovag grew up in Turkey, Hungary, and Scandinavia. What happened next in his life is hotly debated by the few connoisseurs of his work; Lovag, who was not only a great inventor of forms, but also of stories, always gave different accounts to different people. It’s said that he was a bomber pilot in the Russian air force during World War II. It’s also said that he sailed from Stockholm to France, where he studied art, worked for Jean Prouvé, and invented a spherical house, which so impressed Gaudet that he contracted Lovag to build a massive one on a rocky slope near Nice. Here, Lovag first tested his spherical construction technology on a small structure that initially stayed vacant, but Lovag eventually moved into this sphere and used what he had learned to design an enormous house next door.

At some point Gaudet lost interest in the project. Lovag, to whom he had given the lifetime right to live on the property, stopped getting commissions and the biosphere started to decay—the front was still a construction site even as the back had already turned to ruins. Lovag lived in his sphere for thirty years without commissions and died in 2014, the only architect who had lived on his own construction site and in the model of his own building.

Self-Empowerment and a Change in the Architect’s Role

Today, the biggest innovations are in residential architecture, and they come from cooperative building groups. This acts as a form of self-help: builders team up and build what they can’t find on the market—architecture in which one can live on one’s own terms through larger partnerships. This deviates significantly from the stacking of often high-margin, medium-sized apartments in functional buildings. Architects aren’t waiting for customers to finally come and give them a job, like depressed private detectives—they commission themselves, design housing, and then look for people who want to live in the same way.

The architects themselves often live in these constructions—as with the architect Silvia Carpaneto, who designed parts of an inner-city lot called Spreefeld along Berlin’s Spree river.Here there are traditional small apartments, but also many common areas and “option spaces” on the ground floor, which deliberately aren’t used for shops but rather as spaces available to the public—as an extension of the city into the building. These can host festivals, exhibitions, and large communal meals. Although the apartments tend to be small—around fifty square meters—residents have access to 150 square meters of communal space, including a rooftop terrace, laundry facilities, and a living room the size of a restaurant. The key to keeping the units affordable is the externalization of many functions that do not necessarily have to happen in the private realm.

Crucial to all cooperative building projects of this type is the elimination of profit. The German building cooperative is very different from building associations whose members rent or sell their apartments when they are completed. The cooperative as a legal form wants to make affordable living space available to its members, who are co-owners and owner-users, and who pay a user fee to the cooperative; speculation on the residential property is legally forbidden. Ideally, a stable group of residents lives together over a longer period of time.

Another example of an infrastructural framework rather than an architectural one is the “foundations and settlers” residential model established by the architects Anne-Julchen Bernhardt and Jörg Leeser for the International Building Exhibition in Hamburg. Here, a concrete block and infrastructure in the style of Le Corbusier’s Maison Dom-Ino is delivered to a site and residents build their own houses inside. This approach is similar to Peter Stürzebecher’s revolutionary self-established building association in Berlin, where residents experimented with cooperative forms of self-government in a building on Admiralstraße 116 in the Kreuzberg neighborhood.

The Colony: house without form—a model for a new community site

As part of the exhibition “Expo 1: New York” at MoMA PS1 in New York in the summer of 2013, artists, writers, musicians, architects, and students offered week-long seminars and workshops on urgent environmental and social concerns. During preparations for the exhibition, the idea was proposed to erect a temporary building in the courtyard of PS1 where participating artists could work and live. It would be a model for a new form of coexistence and collective work, as well as a site where “exhibiting” could be redefined.

The initial plan was to erect a simple wooden structure, a kind of scaffolding with three floors. Small, simple livings quarters would be built on the two upper floors. A dense belt of plants would serve as a community garden, and would also provide a measure of privacy for the residents. Instead of posting “private” signs to prevent the museum-going public from climbing up to the living quarter, the thicket of plants would create a jungle-like maze of communal space. The threshold would be a labyrinth that provided a sense of privacy without being completely walled off from the outside world.

In conventional apartment buildings, private space is maximized at the expense of communal space. In the colony at PS1, however, private living space was to be kept small—just enough to accommodate a bed, a small table, a kitchenette, a shower, and a toilet—so that ample communal space was available. The areas between the living quarters could be used by the residents any way they wished—to hang hammocks, plant vegetables, set up chairs, and so forth. The ground floor would house a collective kitchen with a long table open to guests. Readings, film screenings, and workshops would be held here.

The construction contract for the colony was given to A77. They erected the scaffolding, but the living quarters were replaced by camping trailers and tents. Communal showers and restrooms had to be built for budgetary reasons. However, the open space on the ground floor worked. Guests came almost every day for lectures and performances. Visitors mingled with the residents and everyone was allowed to watch and participate in discussions. The colony was a laboratory for a new architecture of hospitality, a pilot project that questioned how much privacy people really need and what spaces are conducive to building community. It was built with that which comes before and after construction; it wasn’t separated from its environment by walls, and it didn’t open itself through doors. It worked more like a sponge that absorbed the outside world.

Open structures that produce through the concept of infrastructure rather than the concept of architectural, form-oriented building have more than a mere technical, supply-oriented, or network-related interest in understanding the concept of infrastructure. Indeed, they offer a new framework for social infrastructure. What exactly does that mean?

The colony attempted to create a countermodel to conventional apartment living by promoting permeability. It provided the spatial infrastructure for a situational definition of multiple uses precisely because it omitted classical architectural elements such as doors, walls, and thresholds. This is infrastructure without architecture. Private space—the capsule into which one withdraws—was not rigidly separated from the common space. In our era of rampant privatization and increasingly hermetic city spaces such as shopping malls and residential complexes, this model of socially oriented infrastructure could have far-reaching consequences.

Tobias Just, “Eine Milliarde neue Wohnungen,” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, October 22, 2010.

Klaus Drömer et al., Housing for Everyone: Affordable Living (Berlin, 2014), 13.

According to the 2005 census, about 35.7 million people live in Tokyo, with a population density of 13,415 people per square kilometer. All data taken from GFK-Bevölkerungsdatenerhebung, Nürnberg 2011.

Alexandra N. Katz, “Half a Million Families Living in Poverty,” Argentina Independent, October 5, 2011 →.

See →.

See →.

See → as well as the excellent volume Building Brazil!, ed. Marc Angélil and Rainer Hehl (Berlin: Ruby Press, 2011).

See Niklas Maak, “Odyssee im Wohnraum,” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, September 10, 2010.

Translated from the German by Beny Wagner