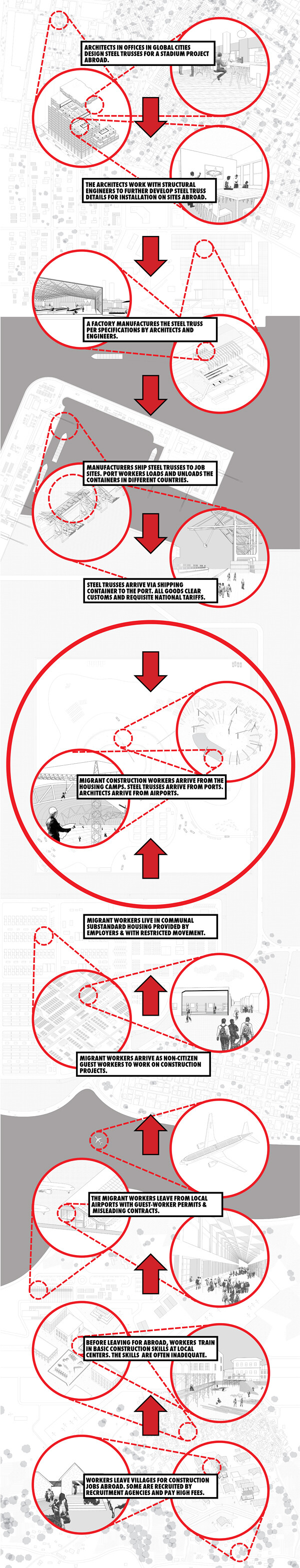

In our recent exhibition at the Istanbul Design Biennale, WBYA? (Who Builds Your Architecture?) installed a “workroom” that allowed visitors to reflect upon the context of transnational building projects and to consider where human rights issues overlap with processes of architectural design and construction. On a large table built for holding discussions and for reading reports on various issues, we displayed a long drawing that mapped the network of a fictional building project. A stadium construction site sat in the center of the drawing, and both sides charted the paths of migrant construction workers as they travel from their villages to job sites as well the movement of a steel truss from design to fabrication to a building site.

In the drawing, a steel truss is designed by architects based on the overall stadium design, aesthetics, and functional criteria. Most likely, aspects of labor required for the truss to be fabricated or installed on site are not considered for its design. Architects use BIM (Building Information Modeling) and other software to design and coordinate construction details with engineers and manufacturers. For large international building projects, architects often collaborate with specialized consultants such as structural and mechanical engineers, fabricators, and sustainability consultants who are often from different countries, atomizing knowledge of the building construction across a wide spectrum of experts. Factories may not be located in the same countries as architects and engineers, clients or the site of the building project. Architects and consultants may visit the factory to review a prototype or mockup of the truss. Production line workers at the factory may or may not be unionized, or work with fair labor practices. A crew of port workers including handlers, train operators, drivers load and unload the containers in different countries, and those containers must clear custom review and pay requisite national tariffs. Finally, the steel truss arrives at the staging area of the construction site, where the site foreman, subcontractors, and construction managers oversee the installation of the truss in the building by migrant construction workers, possibly referring back to architects’ construction drawings.

We interspersed this mapping of the convergence of global workforces on a building site with reports from sources such as Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International that document the issues facing migrant construction workers. Descriptions of steps in the migratory paths of workers as well as working processes in design and construction processes ended with questions speculating where solutions might intervene. How can architects ensure human rights protections extend to those who build architecture worldwide? How can organizational charts be reconfigured to link complex global interdependencies? How can technologies facilitate new relationships between architects, design consultants, and migrant workers who construct buildings? How can architects advocate for better working and living conditions on building sites around the world?

The project team for WBYA? exhibition included Laura Diamond Dixit, Tiffany Rattray, and Lindsey Lee.

—Kadambari Baxi, Jordan Carver, Mabel O. Wilson