At the turn of the twentieth century, Paris was the center of modernity. Everyone who was interested in modern art and culture wanted to come to Paris, namely Americans, among whom were a couple of my brothers, Leo and Michael. I joined them in 1903. Leo wanted to be an artist, and he rented a space on the ground floor on Rue de Fleurus, then number 27, as his studio. But he soon realized he wouldn’t be an artist, so he decided to collect instead. He had already acquired a number of works by the time I came to Paris.

When I arrived in Paris, I began going around with Leo, looking for interesting works of art. One day, we learned that this guy named Ambroise Vollard had many Cézannes in his shop. So we would, from time to time, come to his place and buy some of Cézanne’s work—mostly small paintings, since we could not afford the larger canvases. We did manage to acquire two Bathers and a Mont Sainte-Victoire watercolor. Once we managed to amass a larger sum we bought a very important portrait of Madame Cézanne.

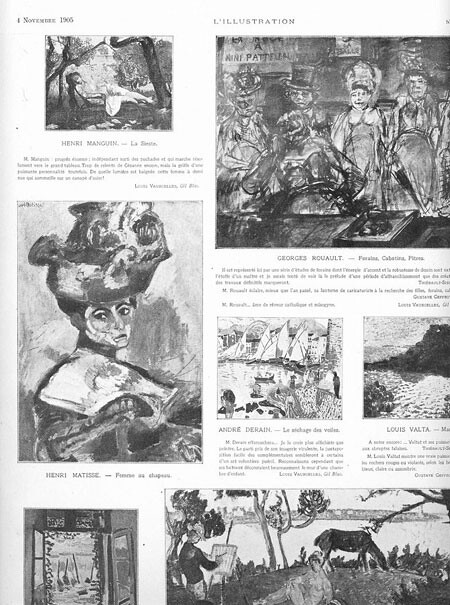

The key moment in our collecting took place during the Salon d’Automne in 1905, when the group of artists known as the Fauves appeared for the first time. We decided to acquire one of their paintings for our collection. We had had a chance to meet Matisse, so we decided to buy a painting from him for three hundred francs. It’s a portrait of his wife. He refused to bargain and we had to pay the full price. In the process we became acquainted with him, and in those days he would come to visit us with his wife.

When we hung the painting in our salon, people started coming to our home at random, asking to see the painting. Finally, we decided to host an open house on Saturdays where anyone interested in seeing our collection was welcome. That is how our Paris salon began.

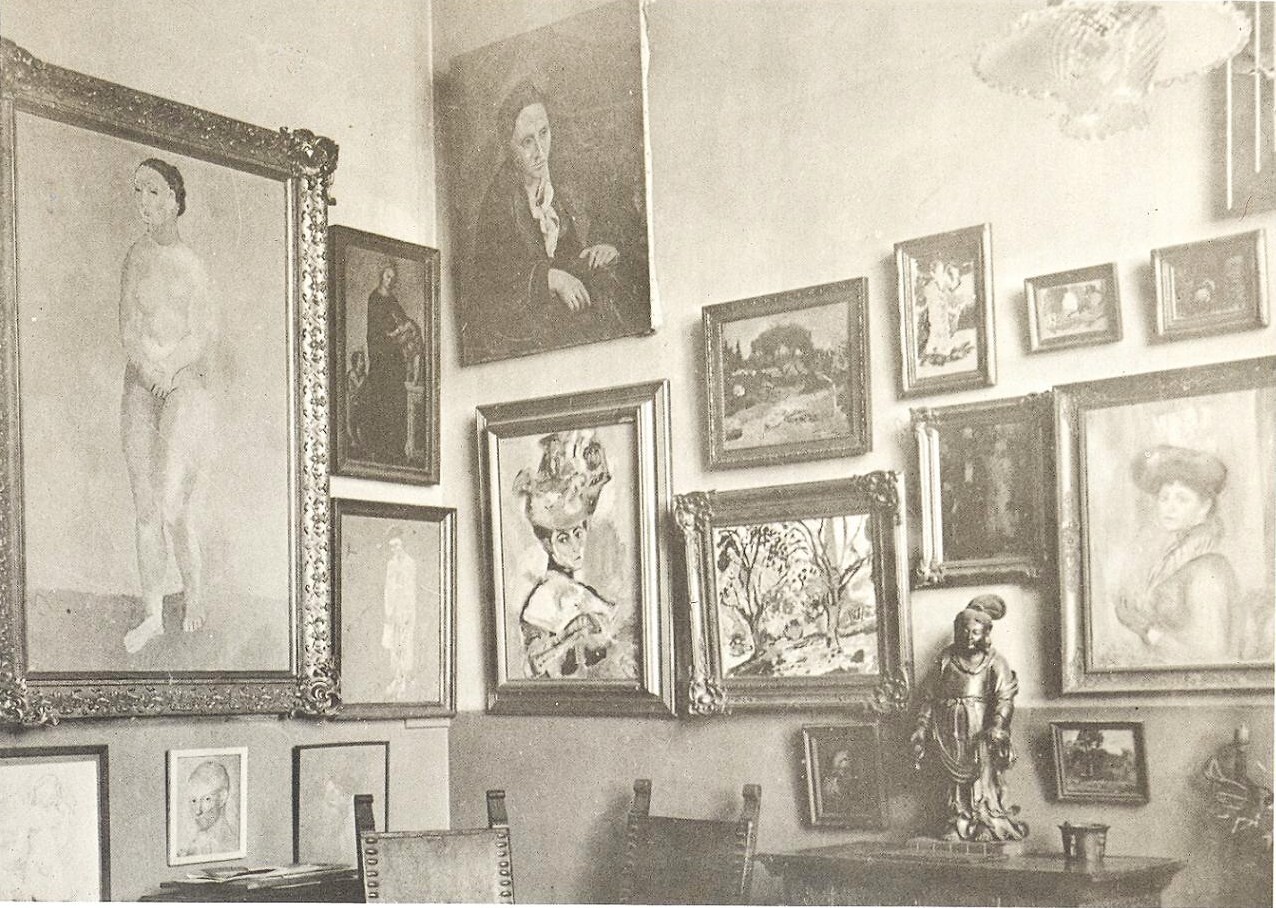

Within two weeks of acquiring our first Matisse, we were lucky to meet a young Picasso at his exhibition in some gallery. We liked him, and a painting of his that became a part of our collection. At first I considered perhaps cutting it in half, since I didn’t like the subject’s feet. But I gave up the idea eventually. In those days, we kept paintings framed; it was only later on that we began removing them and hanging the paintings without frames.

Gradually, Pablo and I began spending more time together and at some point he began painting my portrait. I didn’t like it back then and Pablo was also not happy with the face. Before leaving for Spain he painted it over. After he came back two months later, he painted my face from memory, without seeing me. When the painting was finished a friend came to see it. He noticed that the portrait was very good, but that it didn’t look like me. Pablo immediately replied: “Perhaps not now, but it will,” and indeed, this portrait is how most people know me now. Today it is hanging at the Metropolitan Museum.

After a few years our collection grew, and we were having more and more visitors, particularly from the old country. One day our friend Man Ray came to visit us and took a photo of me and Alice Toklas sitting in front of the fireplace. A few years earlier, Alice had come to Paris and we became very close, especially after she moved in. Meanwhile, my dear brother Leo left forever.

Music by Matisse is now at MoMA, as is Boy Leading a Horse by Picasso, which was once in our salon. And a portrait that was a study for Les Demoiselles d’Avignon is at MoMA as well. The Acrobat painting by Picasso, acquired from me by the Russian collector Ivan Morozov, is now at the Pushkin Museum in Moscow. Three Nudes was acquired from me by another Russian collector, Sergei Shchukin. It was hanging in his mansion in St. Petersburg. It was later nationalized by the Soviet authorities. And it is now hanging in the Hermitage in St. Petersburg. So you see, this collection is completely dispersed.

In the early 1900s, across the Atlantic, another city was emerging as a vibrant and dynamic metropolis: New York.

From the European perspective, America and New York were perceived as a cultural province, not only back then but for many years to come. This is why many Americans interested in art and literature, like my family, would come to Paris, considered then to be the cultural center of the world. Many Americans would come over just to visit Paris, and I remember some came to see our collection, which became quite a popular destination with all these Cézannes, Matisses, and Picassos that hung on our walls.

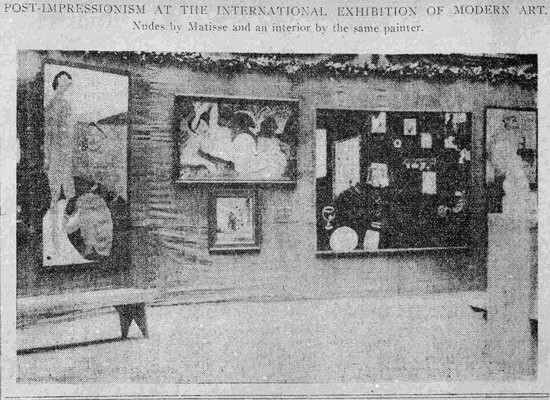

One of those people from New York who came to visit our salon, some time in 1908, was Alfred Stieglitz, already a famous photographer. Stieglitz was very much impressed with our collection, and when he returned to New York, he was the first to exhibit Picasso, and later Matisse, in that city. It was around 1910–11. There is a direct connection between our collection and Stieglitz bringing these artists to the United States. Another connection is the 1913 International Exhibition of Modern Art, known as the Armory Show, where the Matisse nude from our collection was exhibited. The Armory Show selected the Liberty Tree as its symbol and its slogan was “The New Spirit.” It took place in the 69th infantry armory building on Lexington Avenue.

When we look through the Armory Show catalog of that year, we notice that artists are listed as individuals and not according to their nationality, as was commonly the case in those days for an international show. This individualism would later become standard for the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and today for the art scene in general, as a sign of internationalism.

The Armory Show was initiated by a group of American artists and collectors who wanted to somehow shake up the scene, which was very academic and conservative, by bringing the most avant-garde art from Europe. They also included many local artists, and the majority in the show were Americans. But the most daring, controversial art came from Europe. The organizers invited artists such as Matisse and Brancusi, as well as Cézanne, Picasso, Duchamp, and Picabia. In the US these artists became synonymous with modern European art. That invitation also influenced Americans to start collecting this kind of European art. Gradually, the avant-garde group of European modern art was being perceived and interpreted within the US as mainstream modernism.

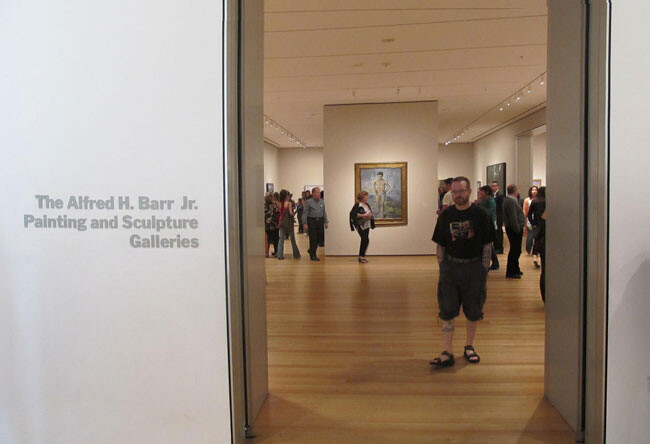

By the 1930s New York was already a metropolis, and at that time perhaps the world’s greatest city. In 1929, a group of collectors and enthusiasts rented a five-room space in the Heckscher building with the idea to open what would become the Museum of Modern Art. It opened with the loan exhibition of four European Postimpressionist painters: Cézanne, Gauguin, Seurat, and van Gogh.

This was a pretty safe choice of well-established artists at that time. The selection of only European artists would also anticipate the future orientation of this museum. In the following years, it remained a museum in name only: it didn’t have its own building, or a collection, and the exhibitions that took place there were loaned. Technically, one could buy a painting at MoMA in those days. In addition, its name was an oxymoron. I remember when a young Alfred Barr visited me in the Paris salon a year earlier, in 1928, and mentioned his plans for a new modern museum. I was a bit amused. I told him: “That’s nice, but how can it be both a museum and modern?”

Lillie Bliss, along with Abby Rockefeller and Mary Quinn Sullivan, were the founding mothers of the Museum of Modern Art. They selected a young fellow, twenty-seven-year-old Alfred Barr, an art historian from Harvard, to become the director of the museum. The second MoMA exhibition was about contemporary American art and was titled “Nineteen Living Americans.” This would be the first in a series of exhibitions of American art held at MoMA that would have a number and the word “Americans” in its title. On the list we recognize the familiar names of the early twentieth-century American modernists.

So at that point the Museum of Modern Art was kind of a strange place. It didn’t have its own space and didn’t have a collection. Naturally, people like Barr began to think about what the Museum of Modern Art could or should be. At some point he came up with a proposal called “Torpedo in Time.” In the center of this torpedo-shaped diagram are the French and the School of Paris. The Europeans and Americans are, for some reason, on the margins. The museum would have a collection of works that would not be older than fifty years. When the works became over fifty years old, they would be transferred to the Metropolitan Museum. Thus the Modern would become a temporary holder of artworks, almost a kind of purgatory for modern art. In this way, those collectors reluctant to give works to this strange new museum would perhaps now more readily do so, knowing that the works would eventually be transferred to the Met.

By the mid-1930s, MoMA moved to a townhouse on 53rd street. Among the staff of the Museum of Modern Art in those days were Barr and Dorothy Miller. In 1936, Barr organized, for the first time, a historical exhibition of modern art. It was a conventional retrospective view of the past, but with some interesting features. Up to this point, art history and museum displays were organized according to national schools. This was a concept introduced with the first museums, like the Louvre, in the early 1800s. And suddenly we had a story told not through national schools but through international movements. A completely different kind of a story.

In this way, Barr retroactively changed the meaning of modern art. He could do this because the American interpretation of twentieth-century modern art at the time was already based in the avant-garde. Its chronology covered the interval from 1890 until 1935—forty-five years. It began with the Postimpressionists (Cézanne) and branched in two directions. One line goes to Matisse and the Fauves, and from there to Non-Geometrical Abstraction, while the other goes to Picasso and Cubism, and from there to Suprematism, Constructivism, and the Bauhaus, to Geometrical Abstraction. Notice that there are no Americans here.

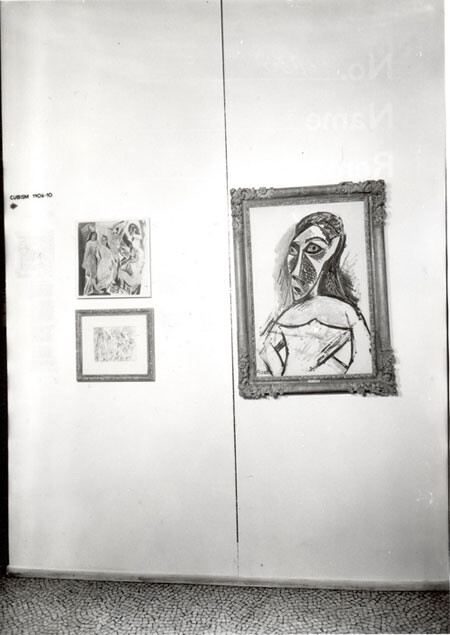

In the “Cubism and Abstract Art” exhibition in 1936, Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon was placed at the beginning of the exhibition, and, consequentially, at the beginning of modern art history. Barr couldn’t get the original, so he decided to exhibit a reproduction. In the two most important countries at that time (France and Germany), when the exhibition “Cubism and Abstract Art” was taking place you wouldn’t have been able to find modern art in museums. And Paris at that time didn’t yet have abstract art in its institutions. Just look at the story of Piet Mondrian, who lived and worked in Paris for twenty years and whose work was acquired for the public collection only in 1978. One could say that if Barr hadn’t put Suprematism and Neoplasticism in his diagram, we would hardly know about Malevich and Mondrian today.

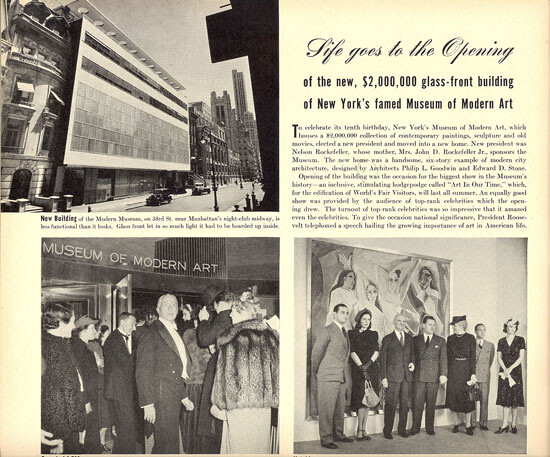

Finally, by the mid-1930s it became clear that the Museum of Modern Art should have its own building. Photos taken during the opening day were published in the May 1939 issue of Life magazine and show proud members of the board in front of the original Demoiselles d’Avignon, which was acquired, by that time, through the Lillie Bliss bequest. Since then, it has become one of the icons of the Museum of Modern Art.

The opening of the new building was accompanied by the tenth anniversary exhibition “Art in Our Time,” and in the catalog are reproductions of the new MoMA building and Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, now in the museum collection. Immediately afterwards, the museum organized the first ever retrospective of Picasso. At the time, from New York’s perspective, Picasso was the most important artist of the twentieth century, and Paris was still the center of modernity.

Then came the Second World War and the liberation, and I was once again the center of attention. Many of the GIs came to see Alice and me. We came back to Paris after spending the entire war in a little provincial village.

In those days I would also visit army units in the barracks. One day an air force crew took us on a flight to Germany. We were all sitting on the terrace of Hitler’s house, known as the Eagle’s Nest. It was a strange feeling to be where Hitler had stood a few months earlier. And the war was still not over.

My friend Picasso was another star of liberated Paris, mostly for GIs, perhaps because of articles like the one published in a 1944 issue of Life magazine. After the war he emerged as kind of a hero, since he did not collaborate during the occupation unlike some his colleagues. At the first Salon d’Automne after the liberation, Picasso was awarded with a one-man show, where he exhibited works from the previous few years. The exhibition was visited by the American general Robert E. Lee. Soon after, the images of gendarmes in the Picasso exhibition started to emerge in the Paris press. Strangely enough, Picasso’s paintings were placed in the gallery to protect them from Parisians. According to Barr’s account in this 1946 book, the reason is that some groups of Parisians started attacking Picasso’s paintings. This must have been very confusing, especially to Americans such as Barr and Sidney Janis, who had a hard time explaining why it was that in Paris, the capital of modern art, Parisians were attacking Picasso, the most important modern artist. Not only that, they were removing paintings from the walls, a very strong emotional action. There were beaux-arts students staging demonstrations in front of Picasso’s studio, wanting to burn his paintings. If this was happening in Paris, what was happening in the rest of Europe? That shows the degree of disconnect that existed in Europe after the war about twentieth-century modern art, in comparison to the story that was being shaped at MoMA.

This could explain the reasons for the comprehensive exhibition of modern art titled “20th Century Masterpieces,” organized by the Congress for Cultural Freedom, to be shown in Paris and London, the capitals of major US allies. James Johnson Sweeney—formerly curator of MoMA and now the director of the Guggenheim Museum—was selected to be the curator. Nicolas Nabokov, the director of the Congress, wrote to Sweeney on behalf of Jean Cassou from the Paris modern museum. He begged Sweeney to bring The Sleeping Gypsy and Les Demoiselles d’Avignon from MoMA. For some reason it didn’t happen, and these two paintings were not included in the show. While reading the names in the catalog we will notice that, although the curator was an American, the exhibition was based entirely on European modern artists and that almost all of them, like Kandinsky, Kirchner, and Klee, came from American collections. In other words, it was the Americans who were bringing European modern art to Europe, including Marcel Duchamp, and even four Suprematist paintings by Kazimir Malevich.

We may also notice that the selection was avant-garde oriented according to the already established MoMA narrative. Also, the artists are listed as individuals, regardless of their nationality, something we saw earlier in the Armory Show catalog. Although the title was “20th Century Masterpieces,” it seems that an American curator decided to re-establish the modern art forgotten in Europe only through European artists.

To understand the difference between the American and European interpretations of twentieth century modern art at that time, it would be helpful to take a look at the 1954 catalog of the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris, printed ten years after the war. Their chief curator at the time was Jean Cassou. The floor plan contains some familiar names and phenomena that are associated with the Paris art scene, but also some not-so-familiar names. However, the real meaning of this structure, the real nature of this museum of modern art, becomes clear when we reach the third floor. Among many rooms there was one at the very end, room number 31.

From a close-up we could learn that the name of this tiny room is “Écoles Étrangères”—Foreign Schools, that is, the rest of the world. So the rest of the world, according to the Museum of Modern Art in Paris, is placed in Room 31. And if you think now of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, according to this Parisian way of structuring art history, it consists entirely of foreign schools. From the New York perspective, the entirety of MoMA would in fact be Room 31.

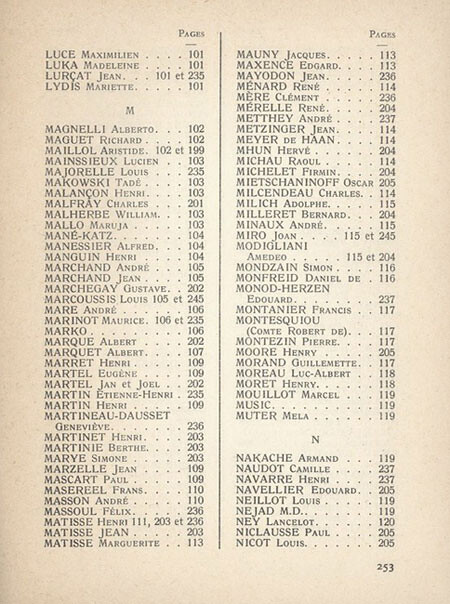

If you look at the names of the artists in the Paris collection under letter M, you won’t find Mondrian, or Magritte, or Malevich. And there are also no artists like Marcel Duchamp or Kurt Schwitters. Many of the key artists important for Barr’s story are not in this collection. So what kind of story of modern art could be told based on this collection? Definitely not the one we know today.

Images selected by e-flux journal.