On March 7, 2015, the day e-flux journal no. 63 is published, I receive a text message from my colleague Younes Bouadi. “The e-flux website is hacked,” it reads. Upon opening the site, an Islamic chant fills my room. An image, imitating the font of the Transformers franchise, appears on my screen: “KHILAFAH WILL TRANSFORM THE WORLD.” A logo next to it shows a blue skull eating away at the face of Guy Fawkes, whose mask became the symbol of the hacker group Anonymous after it was popularized through the comic and subsequent film V for Vendetta. The skull in its turn seems modeled after the Marvel comic and film series The Punisher. The logo seems to represent the ongoing battle between the libertarian-anarchist Anonymous hacker group and the online cells of the Islamic State in Syria and Iraq (ISIS), which in this particular logo identify themselves with the skull of The Punisher. For months the two groups have been waging cyber warfare against one another.1 The hack also carries a signature: “AnonGhost.”

Staring at my screen, I wonder whether the hack is related to my essay in that issue. The essay is on the Kurdish revolutionary movement in Rojava (Syrian Kurdistan) which is currently fighting the Islamic State at its borders.2

The rest of the day, friends from the hacker community help me trace the origins of the hack. The first news is that it might originate from Turkey, which would mean that hackers acting as proxies for the Turkish government are using the Islamic State signature to attack online sources that support the Kurdish revolutionary cause. In that case, the hack forms a perfect analogy with Turkish military support for Islamic State fighters. While the Turkish government publicly condemns the Islamic State and supports the rebooted Coalition of the Willing, in actuality it perceives the Kurdish revolutionaries as its real domestic as well as foreign threat.3

Artist Manuel Beltrán, director of the Alternative Learning Tank, writes me a couple of hours later explaining that AnonGhost has a history of massive online hacks, most notoriously after the killings of members of the editorial staff of Charlie Hebdo on January 9, 2015, and the related attack on a kosher supermarket in Paris on January 11. This is when AnonGhost engaged in a parallel series of cyberattacks in the form of their campaign “#OpFrance.” AnonGhost attacked hundreds of websites, including those of French governmental agencies, French corporations, and even sports clubs, by “canvassing”—defacing—the front pages of the existing sites.4 Mauritania Attacker, a collaborator with AnonGhost in the #OpFrance campaign, explained:

The reason for the attacks on France is because France are racist and they abuse other religions with their stupid democracy and no limits, we don’t call this a democracy, imagine if some Muslims take France flag and burn it and burn a church, how France is going to act!5

Despite this highly political statement, Beltrán explained that AnonGhost operates via various and easily switchable alliances—unlike CyberCaliphate, which acts as the main Islamic State hacker cell:

AnonGhost teamed up with Fallaga Team from Tunisia, the United Islamic Cyber Force, the C7 Crew, Mauritania Attacker, Middle East Cyber Army (MECA), and CyberCaliphate. Since the Charlie Hebdo #Op, AnonGhost established ties with CyberCaliphate related groups and got in a more loose structure that embraces many different ideologies, groups and motivations for different targets.6

At the end of the day, it appeared that the hack on e-flux was not a targeted operation, but simply part of an ongoing canvassing campaign across the internet. AnonGhost made use of a vulnerability in WordPress, the back-end content management system of e-flux and many other sites, allowing for an instant serial hack.

Far more impressive than these “regular” canvassing campaigns was the follow up to #OpFrance, led by CyberCaliphate. On April 9 between 10 p.m. and 1 a.m., CyberCaliphate hacked eleven channels of the French national broadcasting network TV5 Monde, as well as its website and social media accounts, branding them with the slogan “Je suIS IS,” a play on the “Je suis Charlie” slogan and the massive demonstrations that the French government organized in an attempt to forge unity amongst the French population after the assaults.7 The director of TV5 Monde, Yves Bigot, responded as follows:

When you work in television and you hear that your eleven channels have been blacked out, it’s one of the most violent things that can happen to you. At the moment, we’re trying to analyze what happened: how this very powerful cyber-attack could happen when we have extremely powerful and certified firewalls.8

Bigot’s words are worth reflecting upon. Whereas CyberCaliphate hacked homepages and social media sites by canvassing them with Islamic State imagery and messages to the Hollande government, the eleven television channels went fully dark. This appearance of an anti-image seems to be what most terrified Bigot. His freedom of expression is enacted by his claim to the permanency of the image, whatever image that may be. But that does not imply that the black square covering French national television is not an image.

In fact, this anti-image of the black square is at the same time the flag of the Islamic State.9 While representing the annulation of other images—the ones Bigot believes his freedom of expression entitles him to—it still forms an image in and of itself: the black square of the Islamic State is the image that forms the beginning and end of the ever-expanding caliphate. The image that comes before and after all others: the end of the immoral image feed of Western heresy, and the return to the origin of the world and the Prophet’s word (not his image).

These cyber-hacks can be regarded as the iconoclastic equivalent of the destruction of cultural heritage in Islamic State-controlled parts of Iraq and Syria. Recently, international outrage followed a video that the organization released on February 26, in which its members can be seen in the Mosul Museum destroying statues and artifacts dating from the Assyrian and Akkadian empires.10 The outrage was then followed by sarcasm, when several media outlets reported that the objects weren’t originals, but facsimiles installed by the Baghdad government after having moved the actual artifacts to a safe place—as if the “medieval” theories of the Islamic State had stumbled into a kind of postmodern trap of simulacrum.11 This was contradicted by outlets claiming that Adel Sharshab, Iraq’s minister of culture, had said that they were in fact originals.12 Yet more complicated reports claimed that the Islamic State destroyed copies while themselves smuggling the originals abroad to sell on the black market.13

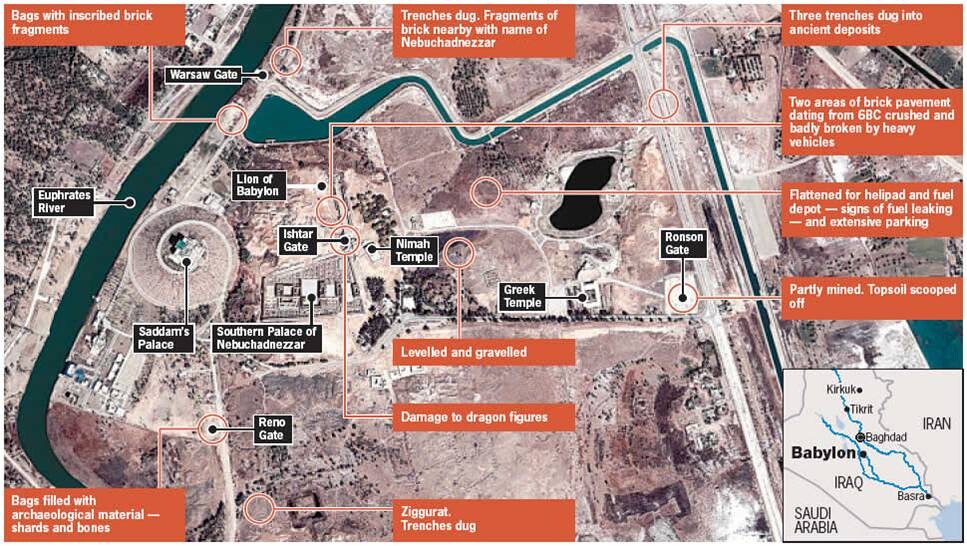

The paradox of the Islamic State’s iconoclastic attempt to rewind history to its own year zero, dating to the birth of its prophet, is that instead of erasing images, it is actively forcing the international community to remember. Little outrage followed the looting and destruction of Iraqi cultural heritage triggered by the 2003 US- and UK-led invasion under the flag of the “Coalition of the Willing,” which allowed the remnants of the already damaged Babylonian temple Etemenanki to be fully eradicated in order to build a prominent military base.14 When it came to enforcing that other year zero, the End of History proclaimed in the name of capitalist democracy, the assault on the memory of the world in the form of ancient Mesopotamia was pronounced as a form of liberation from dictatorship and a “backward” culture—a culture that actually reaches back to about 4,300 years before Christ, where it bore witness to the first city-states of the world, such as Uruk, and the invention of writing, law, and large-scale agriculture. Confronted with this devastation, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld mumbled: “Stuff happens … freedom is untidy.”15

The failure of the American state-building project in Iraq has hit back in the form of the ever-expanding caliphate of the Islamic State, disregarding former colonial boundaries both in the territories of Iraq and Syria, as well as in its online guerrilla campaigns. Once proxies of foreign interests, sponsored and radicalized through decades of colonization, instrumentalization, and invasion, today they have turned the tables. Now that the ever-expanding security apparatus of the Coalition of the Willing clashes with the ever-expanding Islamic State, we actually begin to remember.

Some bizarre truth rang out in an April Fool’s joke by the cultural review Hyperallergic, when it ran an article entitled “ISIS to Exhibit Floating Pavilion of Art Destruction at Venice Biennale.” The article mentions the floating “nomadic” pavilion of the Islamic State, which would be curated by “Talaat al-Dulaimi, ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi’s son,” who is quoted delivering the following statement:

“A few months ago, we realized that there’s a long tradition of what ISIS has been doing in contemporary art, and what better way to continue our mission than to go to the source,” al-Dulaimi said to an astonished crowd of reporters and cultural figures. “By encouraging the public to bring us art—be it their own or pieces taken or ‘liberated’ from others—we are tapping into the increasingly experiential and embodied nature of aesthetic experience. Everyone is talking about the potential for art to go viral, and we know how to do that better than anyone.”16

The article takes a historical tour throughout Western avant-garde art, citing the Italian Futurist leader Marinetti. But what begins as a joke turns eerily serious. Essentially, the joke is on “us”—the “us” in “us and them,” and “us” as in the United States. The joke is on us when confronted with the self-serving distinction between those whose acts of destruction are celebrated as “progress”—stretching from Marinetti’s embrace of a poetic fascism to the US occupying army that settled its military forces on a cradle of human history—versus those whose acts of destruction are denounced as “medieval terror.” If the Islamic State needs to be denounced and fought, then we are also obliged to confront the role of the Western barbarians who have terrorized the region from the onset of Empire’s colonial mandates up to its invasion and continuous occupation since 2003. It is only within the endless, decades-long influx of foreign armies without memory that history can destroy and rewrite itself ever again upon the bodies of peoples and cultural artifacts alike.

The nomadic pavilion of the Islamic State floats: juxtaposing itself with the nation state pavilions that re-enact their nostalgia for Empire in the Giardini: the luxurious heart of the Venice Biennale, where the wet dreams of the powerful are played out like on a geopolitical chessboard, moving artists and artworks like pawns.17 It is a dreamworld in which the US and Israeli pavilions sit side by side, operating their surveillance machinery that reaches far beyond any sovereign state border, while simultaneously fortifying themselves in their pavilions against the black flag that moves with ease through the surrounding canals. And not just there: like a dark body double of Empire, the Islamic State’s pavilion wages its wars in proxy throughout the internet: displaying its monochrome black on the websites of states, national TV channels, and even on the front pages of online journals invested in art and theory.

Let the pages of that same journal be a space where we begin to theorize Empire and its double, for we will need to resist and overcome both.

This article is dedicated to Rijin Sahakian, director of Sada for Iraqi Art in Baghdad, who on April 6, 2015 announced the closure of her institution due to the increasing violence and cultural opportunism that she was confronted with while operating amidst a major political and military tragedy. Sahakian wrote: “Sada’s intention was never to recreate an art ‘scene’ or ‘market’ in Baghdad, nor to privilege nationalist endeavors, which rely on the pretense of loyalty to artificial boundaries, armies and the notion that histories belong solely to particular territories or peoples. History is, in fact, shared. If we, as a community of artists, educators, and citizens of the world hope to understand what is taking place in our education systems, governments and the mechanics of the arts and accessibility, then we must take this global site into consideration and look at what our information—or lack thereof—says not simply about Iraq but ourselves and the systems we take part in every day.”18 For all of us who wish to overcome Empire’s traps, these words hold great truth. I further wish to thank philosopher Vincent W. J. van Gerven Oei for his editorial support in writing this article.

Rick Gladstone, “Behind a Veil of Anonymity, Online Vigilantes Battle the Islamic State,” New York Times, March 24, 2015 →.

See Jonas Staal, “To Make a World, Part III: Stateless Democracy,” e-flux journal no. 63 (March 2015) →.

“Turkey’s role has been different but no less significant than Saudi Arabia’s in aiding ISIS and other jihadi groups. Its most important action has been to keep open its 560-mile border with Syria. This gave ISIS, al-Nusra, and other opposition groups a safe rear base from which to bring in men and weapons … Most foreign jihadis have crossed Turkey on their way to Syria and Iraq … Turkey … sees the advantages of ISIS weakening Assad and the Syrian Kurds.” Patrick Cockburn, The Rise of the Islamic State: ISIS and the New Sunni Revolution (London: Verso Books, 2015), 36–7.

The coalition of #OpFrance consisted of Mauritania Attacker, Virusa worm, Dr SAMIM, Man Rezpector, AnonxoxTn, V0RT3X, Mr.Domoz, HusseiN98D, Mauriitania K!ll3r, CoderSec, Mrlele, Don Maverick RevCrew, Extazy007, Black Cracker, hAxOr tr0jAn, Mr.Ajword, X-Wanted, BillGate, M-c0d3r, n0name-hax0r, rummykhan, Donnazmi, Th3_r3b0rn, Psyco_hacker, TIto Sfaxieno, Stingerbyte, Ghostralia, and Red Hell Sofyan. The group published its list of online targets here →.

“Islamic hackers damage thousands of French domains in opFrance,” Cyberwarzone, January 18, 2015 →.

Manuel Beltrán, personal correspondence.

The propagandistic nature of this campaign was effectively described by French philosopher Alain Badiou: “The confusion reached its climax when we saw the state calling on people to come and demonstrate—in true authoritarian style. Here in the land of ‘freedom of expression,’ we have a demo at the state’s command! We might even wonder if Valls thought about imprisoning the people who didn’t show up for it. Here and there people were punished for not going along with the one minute’s silence.” “The Red Flag and the Tricolore by Alain Badiou,” Verso blog, February 3, 2015 →.

Angelique Chrisafis and Samuel Gibbs, “French media groups to hold emergency meeting after Isis cyber-attack,” The Guardian, April 9, 2015 →.

Inevitably, this brings to mind the reflections of historian Boris Groys on that other historical black square, by Supremacist Kazimir Malevich: “Malevich’s Black Square was the most radical gesture of this acceptance. It announced the death of any cultural nostalgia, of any sentimental attachment to the culture of the past. Black Square was like an open window through which the revolutionary spirits of radical destruction could enter the space of culture and reduce it to ashes … Malevich shows us what it means to be a revolutionary artist. It means joining the universal material flow that destroys all temporary political and aesthetic orders. Here, the goal is not change—understood as change from an existing, ‘bad’ order to a new, ‘good’ order. Rather, revolutionary art abandons all goals—and enters the non-teleological, potentially infinite process which the artist cannot and does not want to bring to an end.” Boris Groys, “Becoming Revolutionary: On Kazimir Malevich,” e-flux journal no. 47 (September 2013) →.

Kareem Shaheen, “Isis fighters destroy ancient artefacts at Mosul museum,” The Guardian, February 26, 2015 →.

Justin Huggler, “Statues destroyed by Islamic State in Mosul ‘were fakes with originals safely in Baghdad,’” Telegraph, March 15, 2015 →.

“ISIL Destroyed Original Artifacts, Not Copies—Iraqi Culture Minister,” Sputnik International, March 12, 2015 →.

“ISIS transferred original monuments abroad, destroyed fake ones in Mosul video,” ARA News, March 4, 2015; Martin Chulov, “A sledgehammer to civilisation: Islamic State’s war on culture,” The Guardian, April 7, 2015 →.

Rory McCarthy and Maev Kennedy, “Babylon wrecked by war,” The Guardian, January 15, 2005 →; Marjoleine de Vos, “Archief in scherven,” NRC Handelsblad, April 4–5, 2015

Cultural Property Training Resource, “The Impact of War on Iraq’s Cultural Heritage: Operation Iraqi Freedom” →.

“ISIS to Exhibit Floating Pavilion of Art Destruction at Venice Biennale,” Hyperallergic, April 1, 2015 →.

See Jonas Staal, Ideological Guide to the Venice Biennial (2013) →.

Rijin Sahakian, “On the Closing of Sada for Iraqi Art,” Warscapes, April 6, 2015 →.