I say therefore that likenesses or thin shapes

Are sent out from the surfaces of things

Which we must call as it were their films or bark.

—Titus Lucretius Carus, De rerum natura1

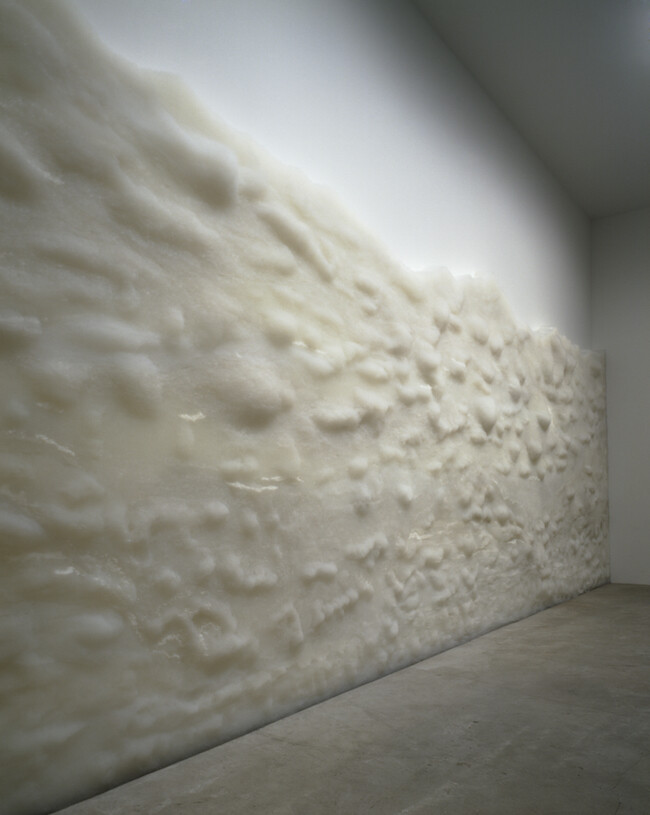

In reflecting upon the nature of things, Lucretius suggests that we consider surfaces as anything but superficial. Yet, despite such consideration in antiquity, there has been a tendency in recent times to denigrate surfaces as just that. But why attach a negative connotation to what is a pervasive state of matter? Think of the surfaces we call skin, fabric, canvas, wall, and screen, and how they positively shape our culture, generating contact, connectivity, and communication. These are sites that are able to hold in their structure substantial forms of haptic, material experience; their “superficial” texture is touchable and therefore touching, and it can even convey material relations, creating forms of encounter. This tangible, superficial contact, in fact, is what allows us to apprehend the objects and the spaces of art, turning contact into the communicative interface of a public intimacy.

In this haptic sense, then, surface is a vital site of artistic expression, and the consideration of surface is driving a major process of redefinition in our visual space. It would seem that a form of surface tension is emerging today as a central condition of contemporary visual art and architecture, signaling a refashioning of materiality on our cultural screens.2 Surface is at the center of this process of re-materialization insofar as it constitutes a threshold. As a form of dwelling that engages mediation between subjects and with objects, the surface also can be viewed as a site for screening and projection. The surfaces of the screens that surround us today express a new materiality as they convey the virtual transformation of our material relations. And these screens, which have become membranes of contact, exist in our environments in close relation to the surfaces of canvas and walls—also undergoing a process of substantial transformation. And so it is here—in this meeting place that is surface—that art forms are becoming reconnected and creating new, hybrid forms of admixture.

Once we consider that art, architecture, fashion, design, film, and the body all share a deep engagement with superficial matters, we can observe how surfaces act as connective threads between art forms and also structure our communicative existence. In many contemporary artworks, the surface is not an incidental part of the work but is rather pushed to the limit of its potential to become the actual core and structure of the piece. A resurgence of interest in ornament and texture is occurring in both art and architecture today, and this process that makes ornament into structure engages a renewed form of hapticity and texturality. In an aesthetic of minimalist simplicity, attention to material defines a surface condition that is an affirmation of materiality in the largest sense of that term. As textural matter builds up planes of perceptual intersection between inside and outside, a thick, layered space of interaction between subject and object—and between interior and exterior—emerges in time. In this way, such a pliant surface becomes capable of retaining the inner structure of temporality and the folds of memory in its material substance. It can also express the sensorium of affects, the sensations of mood, and the sensuality of atmosphere. It is in this sense that surface can be read as an architecture. Not only does it constitute a space in itself; it is a maker of transitional space.

Consider, for instance, how tensile this superficial spatiality may be as it takes shape in the elegant art of Tara Donovan, who creates surface encounters that redefine visual space. Donovan starts with everyday objects—plastic cups, straws, Scotch tape, pencils, pins, toothpicks—and obsessively arranges them in seemingly infinite series to make large-scale installations. The walls or floors of the installations become landscapes populated by these forms, which, unfolding in apparent replication, are perceived as both organic and inorganic. Surfaces here turn into various formations and also convey a sense of volume. Donovan’s material surfaces evoke a vast range of topographies, from the scientific exploration of inner forms to the aerial mapping of cityscapes. Her pliant, latticed matrixes extend from geologic to biologic to nano scales, as if capturing the very volume of their generative processes. Transporting us from exterior to interior geography, they cover the range of our cellular life.

This plastic surface effect is enhanced by the artist’s frequent use of translucent materials: Elmer’s glue, in Strata (2000/2010); Scotch tape, in Nebulous (2002); monofilament line, in Lure (2004). Her more recent use of materials such as Mylar and polyester film further enhances the capacity of the surfaces to absorb, reflect, refract, and diffuse light. Untitled (Mylar Tape), from 2007, for example, has the three-dimensional sense of a shimmering wallpaper bas-relief that, in a play of surface displacement between wall and ceiling, takes on the decorative form of a starry constellation. The effect is of an opaque absorption in luminosity that ambiguously shifts. Haze is how it can be described, as in the title of one of Donovan’s atmospheric installations. In Haze (2003), thousands of translucent plastic drinking straws are irregularly piled onto one another, their original, ordinary form transformed as they converge into a vertical plane and are morphed into an abstract, translucent, volumetric surface. Seductive to the touch, this minimally constructed, elegantly textured plane becomes a wall of filtered, reflected light—a screen of surface materiality.

The creation of public intimacy that occurs in surface encounters of the kind mobilized by Donovan is a haptic affair: as Greek etymology tells us, the haptic is what makes us “able to come into contact with” things, thus constituting the reciprocal con-tact between us and our surroundings. We “sense” matters such as shapes, forms, and space tangibly, and this occurs in art as well as in film exhibition as contact becomes communicative interface on the surface of the screen. This is because hapticity is also related to our sense of mental motion, as well as to kinesthesis, or the ability of our bodies to sense the mutable existence of things and movement in space. The mobilization of cultural space that takes place in both cinema and the museum is thus fundamentally a haptic experience of mediated encounters with material space. Usually confined to optical readings, the museum and the cinema need to be remapped, jointly, in the realm of haptic, surface encounters if we are to understand their tangible use of space and objects, the movement that propels these habitable sites, and the intimate experience they offer us as we traverse their public spaces.

There are many aspects to consider in these material encounters. One factor is that hapticity engages a relationship between motion and emotion. In this regard, it is interesting to note that cinema was named from the ancient Greek word kinema, which means both motion and emotion. The fabric of this etymology indicates that affect becomes a medium and also shows the process of becoming that is materially mediated in movement. Film moves, and fundamentally “moves” us, with its ability not simply to render affects but to affect materially, in transmittable forms and intermediated ways. This means that such a medium of movement also moves to incorporate and interact with other spaces that provoke intimate yet public response, such as the art gallery.

Proceeding from this haptic, material, kinematic premise, the motion and emotion of cinema extend beyond the walls of the movie house: they have been implanted, from the times of pre-cinema to our age of post-cinema, in the performative space of the art collection and in the itinerary of the museum walk as well. Moving images have become the moving archive in this twenty-first century: our own future museum.

This notion that vital matters such as memory, imagination, and affect are linked to movement—embodied in film itineraries and museum walks—has an origin that can be traced further back in time, to the moment in modernity when motion became tangibly craved as a form of haptic stimulation. With modernity, a desire for tactile sensation and surface experiences increased, driving an impulse to expand one’s universe and, eventually, to exhibit it on a screen. The “superficial” images gathered by the senses were thought to produce “trains” of thought and to project a personal, passionate voyage of the imagination. “Fancying”—that is, the configuration of a series of relationships created on imaginative tracks—was the effect of a spectatorial movement that evolved further in cinema and the museum. It was the emergence of such sensuous, sequential imaging (a haptic “transport”) that made it possible for the serial image in film and the sequencing of vitrines in the museum to come together in receptive motion, and for trains of ideas to inhabit the tracking shots of motion pictures.

It is this haptic sense of cinematic motion that is materially returned to us today in the architectonics of art exhibition. Think, for example, of the itinerary constructed by Renzo Piano for the exhibition space devoted to the collection of Emilio Vedova’s artworks, which opened in Venice in 2009 in the restored salt warehouse that had once been the artist’s studio. Piano mobilizes a form of exhibition that uses the actual motion of cinematic montage to activate the mnemonic assemblage and surface materiality of an art collection. This is a museum in movement, where the paintings glide through the space, literally moving in sequence on tracks that are reminiscent of filmic tracking shots. The material of the canvas here turns into a potential screen. The spectator becomes a passenger sent on an architectural journey that retraces mental itineraries, and this cinematic-architectural walk “sets” artistic memory not only in place but in full motion. In such a way, the cinema imaginatively rejoins the museum as a collection of images—a montage of textures and surfaces—that activate ideas and feelings, which are haptically bonded in the “re-collective” itinerary of spectatorship. The filmic voyage, like the museum’s promenade, turns into a transformative journey as the architectonics of memory becomes a mobile, corporeal, emotional activation of public intimacy. And thus a surface encounter is mobilized, on the skin of such things as canvas, wall, and screen, as art, architecture, and film become activated together in moving, material ways.

Titus Lucretius Carus, On the Nature of the Universe: A New Verse Translation by Sir Ronald Melville (Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1997), 102–3.

For an extended treatment of this subject, see Giuliana Bruno, Surface: Matters of Aesthetics, Materiality, and Media (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014).