More than a decade ago, Rem Koolhaas published his widely circulated essay “Fragments of a Lecture on Lagos” as part of a Documenta 11 platform in that city devoted to African urbanism.1 Koolhaas went on to consider the status of Lagos, which seemed to have an aura of “apocalyptic violence” and of a “smoldering rubbish dump.” A series of further enquiries revealed new informal networks entering the interstices of older, decaying infrastructures. Finally, it was a crucial helicopter ride by which Koolhaas showed that Lagos, rather than bordering permanently on chaos, functioned as a series of functional correspondences, with a dynamic “confrontation of people and infrastructure.” This clinching aerial insight followed a familiar trend in the history of architecture. It was through Corbusier’s flights in Brazil in 1929 and in colonial Algiers that he formulated his claims for a new form of urban imagination, distinct from ground-level perception. Thus, after one of his Brazilian flights Corbusier wrote ecstatically:

From the houses, no one sees [Rio]. There is no more land to build upon … There are nearly a dozen bays, closed, isolated. If you walk through the maze of streets, you rapidly lose all sense of the whole. Take a plane and you will see, and you will understand, and you will decide.2

Despite or because of its revelatory encounter lineage, the Koolhaas essay suggested that there was an emerging “instant urbanism” in Lagos beyond the design and designation of postcolonial planning. Its significant limitations notwithstanding, this altogether rare encounter of global architecture with postcolonial urbanism shed light on a dysfunctional-productive space of infrastructure, where constantly moving networks bypassed states and the language of sovereignty.3 In fact, for some time now, the problematic of circulation has emerged as a new theoretical challenge for debates on infrastructure beyond appearing as a familiar adjunct to neoliberal commodity economies and space-time compression in global capitalism. But first, for a bit of context, let’s rewind to the 1950s and the early 1960s.

Talk of Sovereignty

The 1950s saw a tribe of modernist planners and architect-adventurers who ventured to the newly independent countries of Asia and Africa like modernized versions of nineteenth-century European colonial travellers. Le Corbusier in Chandigarh, Doxiadis in Islamabad, and Buckminster Fuller in Africa and India were all part of this traffic to the Third World. Pushed by local regimes to set up showcase cities, and even by US and Soviet foreign policy coffers, architect-travellers were in fact on the sidelines of a significant urban transformation initiated by lesser-known transnational urban planners and designers who worked to plan and develop actually existing cities with large populations, such as Delhi, Lagos, Beijing.

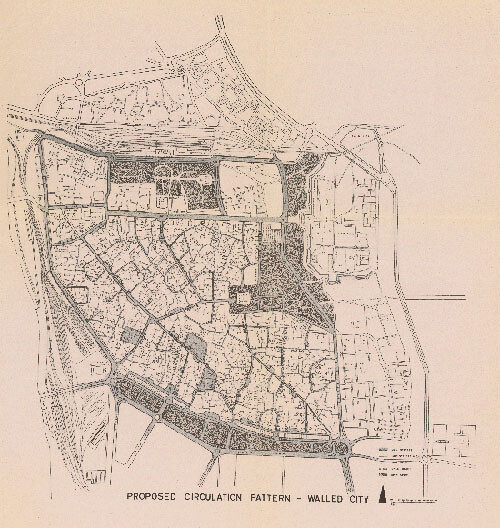

In 1950s Delhi, for instance, the Ford Foundation sponsored a major exercise by US urbanists to design a city masterplan. Leading the team was Albert Mayer, regionalist architect from New York, who had collaborated closely with Lewis Mumford in the 1940s. Mayer had done the first masterplan for Chandigarh, which formed the basis of Corbusier’s larger, better-known interventions. The Delhi Masterplan designed by Mayer and his team incorporated a technocratic grid that would deflect migration flows to the periphery, and protect an urban core that assured sovereignty for postcolonial power. It was the model of the city as an urban machine, with neighborhoods as cellular units, linked by a technocratic hierarchy of functions and power. This was a model city with a centralized command regime, with designated legal subjects. The design was a dramatic performance of postcolonial sovereignty for the new regime. The nationalist city would oversee the proper circulation of people and things through careful zoning and state control of all land. This would purge the circulatory corruptions of the Moghul city, with its mixing of bazaar and residence, human and animal, all of which was seen by the US planners through the pathologies of 1950s modernization theory and Cold War liberalism. Infrastructure itself would designate the form of the city, and resolve what was seen as the ultimate postcolonial shame: poverty and the urban slum.

In a way, this model became a liberal design narcotic for the postcolony of the 1960s. The Ford Foundation sponsored the largest urban project in the world in Calcutta, funding international planners, architects, and sociologist consultants. Western design and engineering firms successfully pitched urban modernization projects in Latin America, Africa, and Asia.

The last few decades have seen the unraveling of this model of urban planning, a tiringly familiar story that played itself out in Asia, Africa, and partly in Latin America. In Delhi, for example, the very forms that the technocratic machine sought to control—economic proliferation, urban sprawl, pirate markets, and migration—all imploded and rendered the control model inoperable. The exact infrastructures that were the hallmark of a new modernity—electricity, roads, water pipes—became locations for new conflicts and claim-making by subaltern populations. The already tottering planning machine splintered, and the technocratic hierarchies of the plan became meaningless. As urban regimes lost the ability to sustain the definitional aspects of the city, infrastructures became the site of new experiments. Pirate cities saw populations poach existing sites: overpasses, unused urban land, abandoned spaces. Remarkably, almost to the letter the post-planning mise en scène resembled Deleuze’s fragmentary notes on “control society.” Deleuze had suggested that modulation, rather than old-style discipline, transforms the rhythm of movement, blurring entry and departure points. Control society was “like a self-deforming cast that will continuously change from one moment to the other, or like a sieve whose mesh will transmute from point to point.”4

Remarkably, just a few years before this time, Jean Baudrillard’s 1977 text “The Beaubourg-Effect” had confidently announced the obituary of radical movements of urban circulation.5 Ostensibly a critique of the Renzo Piano/Richard Rogers Pompidou Centre complex in the Beaubourg area of Paris, Baudrillard’s essay connected information, transparency, the circulation of people and fluids, and the death of the social project associated with 1968. For Baudrillard, the Beaubourg “thing” was a “carcass of flux and signs, or networks and circuits,” its “cool” exposed tubes on the building suggesting not transparency, but a strategy of anxious spatial “deterrence.” Along with its over-informationalized exterior, the building’s model of endless internal circular movement was an image of controlled socialization. At the heart of the rhetorical populist gesture incorporating the mass was a shift:

Because this architecture, with its networks of tubes and the look it has of being an expo or world’s fair building, with its (calculated?) fragility deterring any traditional mentality or monumentality, overtly proclaims that our time will never again be that of duration, that our only temporality is that of the accelerated cycle and of recycling, that of the circuit and of the transit of fluids.6

What emerges in the tense encounter between the design and the flow is a critical mass “no longer tied to specific exchanges or to determinate needs but to a kind of total universe of signals; through this integrated circuit impulses travel everywhere in a ceaseless transit of selections, readings, references, marks, decodings.”7 Notice how in Baudrillard’s post-Marxist moment, the signal has replaced abstract labor/money, dis-embedding the “mass” in the process of circulation. Frankly, Baudrillard’s prescient synthesis of McLuhan and Adorno did not do much for me when I first read it some years ago; but today we can better grasp his points about the disjunction between the different orders of circulation: the cool surface and the uncontrolled, unknowable “mass” it sought to incorporate. If the Beaubourg design proclaimed the end of the old social model of revolutionary politics, the only hope was a post-universal, “ungraspable” and “non-extendable” model of circulation.8

What if a different constellation emerged from this transaction of populations and information in “ceaseless transit,” one that forced us to ask questions about the political itself? This question has come to the fore in postcolonial cities, and I suspect in every other urban form across the globe.

A Sensory Infrastructure?

Postcolonial urban governance operated within a code that functionally separated the social and the medial. The domain of the social was demarcated by welfare and the governmental nurturing of a healthy population. The medial occupied the realm of leisure: to be serviced by infrastructural sites like newspapers, film studios, television networks, cinema theaters, radio stations. Welfare was the domain of the state and politics, and the institutions of the medial were managed by regulators and censors. Governmental power periodically filtered and differentiated two orders of circulation: of people and things, and of public affect—where populations were kept away from the dangers of “sensuous provocation.” Once the movement of people and things began overlapping with circulating media, this postcolonial design stood compromised, putting the “social” into question. Via a Kittlerian lens, we could say that if media “determines” our urban situation by becoming its infrastructural mesh, it simultaneously undermines and implodes the representational models of postcolonial power.9

By the late 1980s, infrastructures became the center of media circulation by way of entangling people, objects, knowledges, and technologies. Following the cassette boom in the 1980s, media infrastructures expanded rapidly in the postcolonial world, in the context of a large urban informal economy. Media formats and platforms have proliferated along with an endless profusion of personalized media gadgets that range from expensive smartphones to low-cost models used by the poor. The transformation of postcolonial life into a dynamic technological culture is wide ranging, affecting all sections of the population. The majority of India’s citizens now have cellular phones, through which they have access to audio, video, and still images. With the cellular phone, a growing section of the postcolonial population is now the source of new-media output—which in turn links to online social networks, mainstream television, and peer-to-peer exchanges of text, music, and video.

These expanding media infrastructures have formed a dynamic loop between fragile postcolonial sovereignties and informal economies of circulation.10 Indifferent to property regimes that come with upscale technological culture, subaltern populations mobilize low-cost and mobile technologies to create horizontal networks that bypass state and corporate power. Simultaneously, we witness the expansion of informal networks of commodification and spatial transformation. This loop shapes much of contemporary media circulation, where medial objects move in and out of infrastructures and attach themselves to new platforms of political-aesthetic action, while also being drawn to or departing from the spectacular time of media events.11

As state authority weakens either through economic crisis, neoliberal reforms, or war, infrastructures also perform a kind of “doubling” role. Two decades ago, an essay by Achille Mbembe and Janet Roitman intimated this churning:

Fraudulent identity cards; fake policemen dressed in official uniform; … forged enrollment for exams; illegal withdrawal of money orders; fake banknotes; the circulation and sale of falsified school reports, medical certificates and damaged commodities … It is also a manifestation of the fact that, here, things no longer exist without their parallel. Every law enacted is submerged by an ensemble of techniques of avoidance, circumvention and envelopment which in the end, neutralize and invert the legislation. There is hardly a reality here without its double.12

This doubling of infrastructures may also produce a poetics, with new aesthetic and political possibilities. This is powerfully expressed in the Bombay artist collective CAMP’s recent video project From Gulf to Gulf to Gulf.13 The project tracks the movements of commodities, local ships, and sailors across the contemporary turbulent geographies of the Indian Ocean: Somalia, Aden, Sharjah, Iran, Pakistan, and Western India. In Gulf to Gulf to Gulf, sailors’ cell phone videos generate connections between sailing routes, the death and life of ships, and work time and dream time. The film portrays the edge zones of the sea, moving beyond the familiar tropes of maritime piracy, terrorism, and war. By using the infrastructural turn for a conversation on space, aesthetics, and politics, Gulf to Gulf to Gulf moves easily between the circulations of people, media, and commodities.

Circulation Takes Command

William Mazzarella suggests that postcolonial censorship’s “performative dispensation” was to play both police and patron, in a chronic state of cultural emergency that is the condition of mass publicity. This was a foundational transaction between the unstable “open edge” of mass publicity, and the assertion of sovereign power, whose authority was periodically evoked to filter authorized and unauthorized sensuous transgressions.14

The management of public affect through authorized circulation has broken down all over the postcolonial world, if not elsewhere, disrupting older transactions between sovereign power and a population seen as susceptible to sensorial powers. Media has become the infrastructural condition of living, rather than existing as distinct, regulated sites like the cinema theater, or as celluloid. The always emergent potential (or “becoming virtual”) of mediation is now a generalized condition of affect-driven postcolonial media modernity in India, if not most parts of the world today.15 The older police function of postcolonial governance was to privilege select circuits of media exhibition and consumption. Today, new forms of unauthorized publicity have actively destabilized this regime and fed into new loops of circulation. Blurring and confusing the distinctions between the legal-nonlegal, private-public, fact-artifact, and governmental-nongovernmental, the new interventions span homes, governmental offices, political parties, individuals, industrialists, and just about all walks of life.

This has been accompanied by thousands of everyday acts from a media-enabled population. A volatile, sensory infrastructure emerged, combining pirate tactics, media forms, and paralegal space. New, unregulated forms of media (audio, video, images) began to rapidly circulate from urban populations hitherto seen solely as social-political actors. These interventions operated alongside an expanded and often chaotic governmental surveillance regime, as well as a visceral media archive that emerged from the private collections of accident witnesses, estranged lovers, paramilitary torturers, and ordinary citizens with camera-equipped phones. From the initial affect-charged moment of publicity, this media archive joins the global traffic in poor images, moving away and attaching to new environments.

This ever-expanding circulation engine has significantly challenged the premises of postcolonial urban design, which at its origin was indexed to stable arrangements of people and things. The category of the population, seen as solely an object of nurture and welfare, is now increasingly unsustainable. What do you do when social-political actors are also media proliferators? There is a conceptual (and productive) blur between affect-driven infrastructures and the movement of media. Ficto-graphic atrocity stories (images, sounds, videos) circulate and attach themselves to sites of violence; in India, for instance, “fake” videos have been held out as reasons for disturbances in various cities and for the intimidation and killing of minority populations.

Crowds or Shadows?

The circulation engine creates a surplus of shadow networks. In older modes of governance in India, paper-based databases (electoral rolls, ration cards) produced by state functionaries intersected with political mobilizations at local and city levels. Colonial power was based on a powerful deployment of paper-based information systems for routine policing as well as the management of migrants, epidemics, and cross-border movements. After independence, the postcolonial regime drew significantly from this system, by aligning it to republican democratic politics. As typical postcolonial technologies of visibility, paper-based information systems allowed the regime to manage urban residents through systems of inclusion and exclusion, while for political groups, entry into the database constituted an important vector of everyday life. Such political strategies could range from selective, strategic entry into some databases (electoral rolls, ration cards) with fuzzy land-ownership patterns and informal systems of electricity and water.16 In short, entry into one information system could coexist with tactical invisibility in another. Small traders and migrant residents of squatter settlements moved in this shifting information ecology.

In the contemporary digital era, this is a neurophysiological zone amplified by the mix of mobile computing objects, moods, and sensations. Provisional networks form around these temporary connections: Bluetooth sharing of media by sailors, urban proletarians, and migrants; shadow libraries moving via USB drives; hawala transfers via text; neighborhood shops that refill phone memory cards with pirate media. Online shadows exist in WhatsApp sharing networks, dancing around regimes and mobile company filters. This is a remarkable infrastructure of agility and possibility.17 Will this become a logical object of a new post-Tardean political economy of propensity?18 This means not just emerging corporate-funded research on proprioception, facial recognition, and gesture, or all the contemporary Big Data rhetoric and the excitement about the algorithmic turn. Emerging players like Alibaba in China and Snapdeal in India dream of tapping the energies of the new urban information ecology, while regimes push for connecting cellular phones to identification. But perhaps not. The dream of stable designation was the ruination of postcolonial design in its powerful heyday, and the current dream of platform capitalism may be no different.19

An architecture of shadows anyone?

Rem Koolhaas, “Fragments of a Lecture on Lagos,” in Under Siege: Four African Cities—Freetown, Johannesburg, Kinshasa, Lagos (Documenta11_Platform4), ed. Okwui Enwezor, Carlos Basualdo, Ute Meta Bauer, Susanne Ghez, Sarat Maharaj, Mark Nash, and Octavio Zaya (Ostfildern-Ruit, 2002).

Cited in Adnan Morshed, “The Cultural Politics of Aerial Vision: Le Corbusier in Brazil (1929),” Journal of Architectural Education, vol. 55, no. 4 (2002): 201–10; 205.

This encounter was thoroughly criticized by various writers for obfuscating the ground realities of Lagos. For a critical response see Matthew Gandy, “Learning from Lagos,” New Left Review 33, (May–June 2005).

Gilles Deleuze, “Postscript on the Societies of Control,” October 59 (Winter 1992): 3–7; 4.

Jean Baudrillard “The Beaubourg-Effect: Implosion and Deterrence,” trans. Rosalind Krauss and Annette Michelson, October 20 (Spring 1982): 3–13; 5.

Ibid., 5.

Ibid.

Pointing to Italian “radio pirates” at the end of the essay, Baudrillard suggested that their real danger to the “system” lay not in their politics but in their “non-extensible” and “dangerous” localization.

Friedrich Kittler, Gramophone, Film, Typewriter (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999). Kittler began his classic text with this sentence: “Media determine our situation, which—in spite of, or because of it—deserves an explanation.” xxxix.

See Brian Larkin, Signal and Noise: Media, Infrastructure, and Urban Culture in Nigeria (Durham: Duke University Press, 2008).

See Sensible Politics: The Visual Culture of Nongovernmental Activism, ed. Meg MacLagan and Yates McKee (New York: Zone Books, 2012).

Achille Mbembe and Janet Roitman, “Figures of the Subject in Times of Crisis,” Public Culture 7, (1995): 323–52; 340.

See Gulf to Gulf to Gulf in the Indiancine.ma archive →

William Mazzarella, Censorium: Cinema and the Open Edge of Mass Publicity (Durham: Duke University Press, 2013).

Lauren Berlant, Cruel Optimism (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011).

Informal tenure rather than formal, title defines urban residence in most postcolonial cities.

It is also a visceral vehicle of terror where political productivity can articulate intimidation, exploitation, and aesthetics.

See Nigel Thrift, “Pass it on: Towards a political economy of propensity,” Emotion, Space and Society 1 (December 2008): 83–96.

See Geert Lovink, Sebastian Olma, and Ned Rossiter, “On the Creative Question – Nine Theses”, Institute for Network Cultures →