A quintessential aspect of aesthetic modernism in the nineteenth century is that it produced not only a body of artworks and a profusion of –isms, but also a body of institutions and a template of practices that, unlike the art itself, were accepted almost without protest by the European and American art public.1 As early as the late nineteenth century, the field of exhibition-making also had isolated examples of figures similar to the independent curator of contemporary art—although, of course, without the institutional support that is usual today.2 One such “proto-curatorial” figure was Joséphin Péladan, who among other things was the founder and director of the Catholic Rosicrucian Order of the Temple and the Grail (L’Ordre de la Rose-Croix Catholique du Temple et du Graal) in Paris. In the 1890s, Péladan organized large group exhibitions as the order’s main public events, in which he presented artists who had been selected in accordance with his very particular conceptions of art. Viewed from today’s perspective, he was a typical independent curator who, at every level and wherever present, defended his “particular position” in art, communicating it through his public image and lifestyle as well.3

Today, Péladan is not well known for his curatorial work, not because he was so far ahead of his time that, say, his contemporaries did not understand him, but rather because, when it came to positioning himself successfully in art with an enduring place in history, he made several “mistakes.” Among other things, despite Péladan’s hard work and the genuinely large influence he enjoyed in his day, he did not do enough, and above all was not sufficiently convincing, to ensure that he would be “right” in art history. He did not persevere long enough in his practice, he was not successful enough in assembling a coherent group of artists, and he was not well connected to the market. Furthermore, he was so extremely pompous and so obviously contradictory that it made it difficult for anyone to take up his cause openly and in earnest. Mario Praz described him as heroic in intention and comic in results.4 Péladan experienced a small revival in the late 1960s, when symbolism as a movement again acquired a certain general importance.5 Hippies, too, found him interesting because of his strange attire, his fascination with magic and the Near East, his rejection of weapons, and the like.

Péladan

A brief look at the life of this bizarre, complex individual is needed if we want to understand his proto-curatorship and compare it with contemporary curatorial practices. Joseph Péladan (1858–1918), as he was originally called (he later changed his first name to Joséphin), was born in Lyons in the family of the fervent Catholic journalist and mystic Louis-Adrien Péladan. He thus acquired his zeal for mysticism and Catholicism from his family, while his delight in costumes, mysteries, unusual rituals, and pseudonyms (Sâr Mérodack, among many others) was common among occultists and artistic circles of the time. We need only recall, for example, the group Les Nabis.6 Péladan carefully crafted his external appearance: he wore long tunics, silk and lace, had long hair and a long beard, and sported eye-catching, provocative accessories.

He travelled in Italy as a young man, after which he arrived in Paris filled with fervor and loudly announced his mission in the press. Among other things, in a review of the 1883 Salon, he wrote: “I believe in the Ideal, in Tradition, in Hierarchy.”7 In short, he declared war on every kind of realism. In 1884, he published his first major literary work, the novel Le Vice suprême, which was followed not only by other novels but also many plays, articles, reviews, and scholarly works on art. He even published two travelogue-type books—La terre du sphinx (on Egypt) and La terre du christ (on the Holy Land)—and some esoteric “self-improvement” books, including books on becoming a magus and becoming a fairy. Among his many other extraordinary accomplishments, he claimed to have discovered a new location of the tomb of Christ. He called his vast cycle of novels La décadence latine: his belief that the corrupt and irreligious Latin race must fall appears as a common thread and motto in most of the works. The novels reflect his fear of democracy and the coming of the barbarians. They deal with mysticism and strange events, and they are usually plotted around Péladan himself in the guise of a literary character. Péladan’s hero is always in pursuit of the Ideal, for which he makes the greatest sacrifices and renounces everything worldly, as deeply infatuated noblewomen try to seduce and distract him. Only rarely is this formula abandoned. Art is normally involved as well—its redeeming potential, the struggle for true art, and so forth. For example, in the novel L’androgyne, Péladan promises to crusade against all that is ugly, all that is vulgar, both in his writing and in real life.8 To this end, he advocates an indivisible art that can take us back to the Catholicism of the Renaissance, which, he argues, produced the greatest number of masterpieces—the highest proof of the existence of God.

Despite his enduring fascination with the occult, Péladan was an idiosyncratic and fanatical Roman Catholic who zealously promoted the Catholic faith. He believed that while the church opposed sorcery, it was not against magic and even supported it. The bombastic fanfare around the publication of his novel Le Vice suprême brought the occultist Stanislas de Guaïta to him, and together in 1888 they revived the Rosicrucian Order (L’Ordre de la Rose-Croix) in Paris. Philosophical differences soon led to internal disputes, and at the start of the 1890s Péladan founded his own Catholic Rosicrucian order, the Order of the Temple and the Grail.

The members of the Order performed works of mercy to prepare for the coming age of the Holy Spirit and, most importantly, sought an inner perfection that would allow them to live a contented life on a perverted earth. The main focal points of the Order’s work were aesthetic, and its most visible public events were, in fact, exhibitions—art salons held regularly from 1892 to 1897. These were typical oppositional exhibitions, which proclaimed that, unlike the once-official Salon and similar contemporary art shows, they were presenting “true” art. This, of course, meant art as it was understood by the enthusiastic curator Péladan, who with great fervor and pomposity invited his chosen artists to exhibit.9

Péladan, the Proto-Curator

What aspects, then, of Péladan’s manner of exhibiting the art of his day make him seem so close to the modern-day curator?

The first is, certainly, the simple fact that, quite unusually for his time, he decided to convey his philosophical and critical views and ideas about art not only in writing but also through large group exhibitions. He evidently decided on the exhibition form because it allowed him to use other people’s works to illustrate and communicate his worldview, and the beliefs he was advocating. This understanding of the exhibition makes his approach identical to that of today’s curators: an exhibition is not only a medium for showing art but also a vehicle that can work toward a variety of goals, for instance, encouraging social renewal. Apart from his love for art, what justified and confirmed Péladan in his commitment to such work was his dedication to a higher goal, the Catholic renewal of society. This, to be sure, makes him ideologically distant from contemporary curators’ commitment to fight global capitalism or support politically correct views, but the principle is basically the same.

Because of this “utilitarian” attitude toward exhibition-making, Péladan is, in fact, already a typical curator with a particular position, one that defines all his projects in a characteristic way and stamps them with a distinctive mark. Turning things around a bit, we can say that by enforcing his own ideas, dictating the messages, using a characteristic “form” for his exhibitions, and choosing very specific artists, Péladan developed a distinct authorial style of curating in which his name alone informed viewers of what they could expect.

Like modern-day curators, Péladan also established his own circle of artists, for whom he was a fervent supporter and advocate. As is true today, the curator’s proximity meant, for the artist, considerable help in becoming established, but also that the curator’s worldview, narrative, and speech would considerably define his art, shaping an interpretation and staking out an understanding of him and his work that he himself might not necessarily embrace.

Furthermore, with Péladan’s work, we can already witness the merging into a single job of the two positions that are usually kept separate in the art world, namely, those of producer and artistic director; indeed, it is this specific combination that gives curators today such extraordinary power. The ability to organize and coordinate numerous large productions thus brings the producer as well a direct means for establishing his ideas, views, and artistic aspirations, since in the process the producer is not divorced from the creative function but rather defines even the exhibiting artists and their work, and conceptualizes the event as a whole. It is understandable, then, that such a curator-as-producer also takes the lion’s share of the prestige and fame, as the greatest part of such bonuses attaches specifically to his name.10

Péladan, the Producer

If, of the two positions just mentioned, we first look a little closer at the producer’s side, we find that Péladan performed this role very well and used work methods that are completely modern. He knew how to acquire devoted collaborators, the necessary funding, and a prestigious venue, and how to promote the event in a way that would attract media attention and the widest possible public. Let us take his first salon as an example.

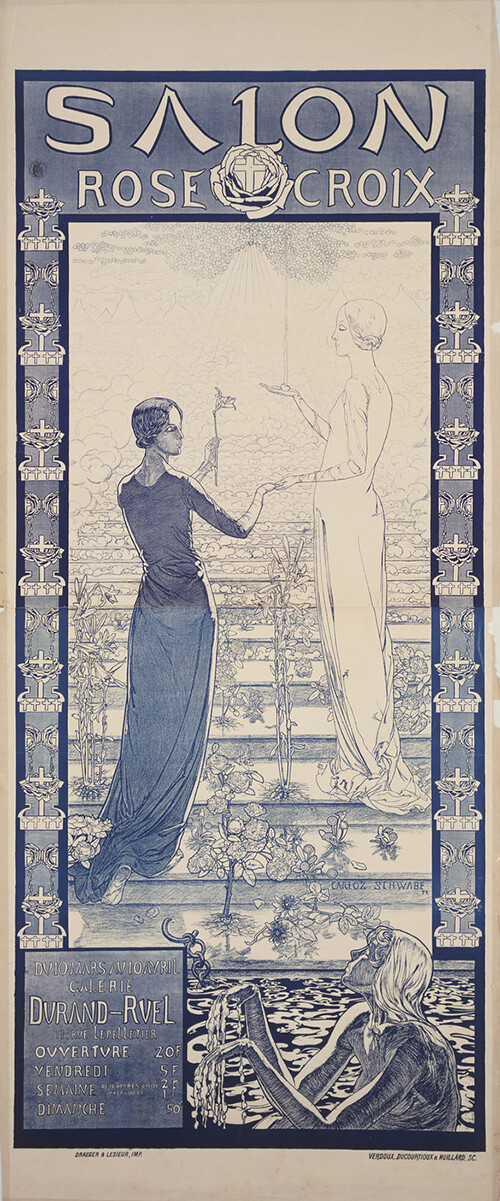

Labelled as a geste esthétique and acta Rosae crucis (acts of the Rose Cross), the exhibition was held at the Galerie Durand-Ruel from March 10 to April 10, 1892. Describing the show in today’s terms, we would say it took an interdisciplinary and intermedia approach, was conceived as an integrated spatial installation—a kind of “environment”—and included many accompanying activities. On the opening night, the exhibition rooms were festooned with flowers and fragrant with heavy oriental perfumes, and the guests were greeted with the prelude from Wagner’s Parsifal as they entered. Among other things, the opening also featured specially composed music by Erik Satie. This whole “circus” (excessive even for those days), which Péladan took in dead earnest, was just what the viewers wanted; they flocked to the show in droves, perhaps looking not so much for aesthetic delights as to satisfy their curiosity and lust for sensation. Those present on the day of the opening included Paul Verlaine, Gustave Moreau, Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, and even Émile Zola, who was hated by the symbolists—names, in other words, that guaranteed the event’s reputation as a prestigious occasion.11 We can conclude that the salon was very successful, despite receiving a mixed response from the critics.12

Péladan solved the problem of funding, and made the social connections needed for success, by involving powerful and influential sponsors in his shows. For his first salon he found such a backer in Count Antoine de la Rochefoucauld, who initially was one of his most important collaborators and also took part in the salon as a painter. De la Rochefoucauld generously supported the first salon financially and put his reputation behind it; he was thus crucially important in creating the initial momentum for Péladan’s salons. Nevertheless, already in the first salon he and Péladan quarrelled a great deal over all sorts of things, and in the end de la Rochefoucauld had no choice but to leave the group. De la Rochefoucauld, the salon’s main financial backer, who held with Péladan the highest position in the Rosicrucian Order, apparently fell into Péladan’s disfavor because, among other things, he tried to win acceptance for some of his ideas about the selection and installation of the artworks at the salon.13

Péladan designed his art project to be explicitly international; he exhibited many Dutch artists, including Toorop, as well as such Swiss artists as Schwabe and Hodler, the latter shone at the first salon with his work Disappointed Souls. Another well-represented group were the Belgians, who also seem to have been the most enthusiastic about Péladan, especially Jean Delville, who for a time served as a kind of ambassador for him and his order in Brussels, and Fernand Knopff, who provided illustrations for his novels.14 Although successful in attracting foreign painters to his salon, Péladan was not particularly successful in his attempts to expand the Order’s network beyond Paris, and its foreign affiliates never really developed.15 Among other reasons, the Order’s involvement with visual art was probably too short-lived for such an expansion; Péladan announced that the Paris Rosicrucian salon of 1897 would be the last, and when it closed, he apparently stopped curating contemporary art.

Péladan, the Artistic Director

Presumably, it was Péladan’s ability and success as a producer and organizer that secured him the interest and participation of a wide range of artists. Left to fend for themselves on the free market, artists in the nineteenth century increasingly saw regular exhibiting and press coverage as matters of survival and became increasingly dependent on—and in an unequal relation to—potential exhibitors.16 Given the comparison with today’s curatorial practice, it is particularly important to underscore that Péladan considered exhibition-making as a subjective creative challenge where he could have his ideas and views recognized and where he could realize his ambitions, while the artist was left to adapt to all this—or otherwise only invited to participate if the curator deemed him suitable. With the exhibition so devised, Péladan then saw it and defended it as, essentially, his own intellectual property, explaining and justifying it from his own personal perspective.

In this respect, Péladan created precise directives for the artists and works he would consider presenting at the Salon de la Rose-Croix. Although the expression “curatorial concept” was not in use at the time, his writings and public statements define in precise terms the kind of art he supported and considered worthy of being shown in the salon. Péladan did, however, conceptualize his exhibition practice in the form of the Order’s art program, which was published as a set of rules. Although the ideas and subject matter of his desired art do not in themselves interest us here (at least not primarily), these rules can be summarized to get a sense of the considerable clarity of Péladan’s concept, as well as the freedom (or lack thereof) he allowed art and the artist.17 He writes in Section II of his rules that the Rosicrucian salons strive “to ruin realism, reform Latin taste and create a school of idealistic art.” In Section III, he says that the order accepts works by invitation only and “imposes no other programme than that of beauty, nobility, lyricism.” Nevertheless, in Section IV he lists “for greater clarity” the kind of subjects that will be rejected “no matter how well executed, even if perfectly”: history painting, patriotic and military painting, “all representations of contemporary, private or public life,” portraits (with rare exceptions), “all rustic scenes,” landscapes, any still life, seascapes, humorous scenes, flowers, and so on.

“The Order favours first the Catholic ideal and Mysticism,” he wrote, followed in importance by legend, myth, allegory, dream, and it wished to see content related to these topics “even if the execution is imperfect.” These rules also extended to sculpture, and busts were not accepted except by special permission. Due to the fact that the art of architecture “was killed in 1789,” the only acceptable works in this field were “restorations or projects for fairy-tale palaces.”18 The preferred technique above all others was the fresco. Drawing, less as a physical than a psychological technique, was also highly favored because the medium crossed the boundary between the earthly and the spiritual. Women were entirely excluded as exhibiting artists.19

To such truly “conceptualized” exhibitions, where the selection of artists was combined with rules about the content, Péladan then added a third level, where through focused writings and statements before, during, and after the event he further imprinted his story on the whole entity thus designed. As eloquently and as loudly as possible, he tried to justify his exhibitions and selections as universal, the most sensible, and the best selections of art at the present moment, and to achieve this, he skilfully employed all sorts of operations that are still being used by curators today. For instance, he was very adept at justifying and legitimizing new artistic positions by juxtaposing them with established antecedents and emphasizing the similarities. Because exhibitions also by this time had an intensive presence in the media realm, his message, in relation to the artist’s, was already clearly in the foreground, especially because Péladan, like the successful curator today, was extremely careful about the media coverage of his events and knew how to make himself a very attractive personality for the press.

Not unlike modern-day curators, Péladan was already criticized for trespassing too far into the artist’s domain—but criticism did no real damage. In response, and in a way quite characteristic of today’s debates on the topic, Péladan would entangle himself in contradictory and contrived-sounding explanations about how he was truly exalting the artist and the artist’s freedom. When it came to displaying his positive, devoted attitude toward the artist, Péladan could be extremely vocal. In the catalogue of the first salon, he wrote:

Artist, you are the priest: art is the great mystery and when your efforts result in a work of art, a holy beam descends on the altar … Artist, you are the king: art is the true empire; when your hand writes a perfect line, the cherubims themselves descend to take pleasure in it as if in a mirror … Artist, you are the magician: art is the great miracle and proves our immortality.20

Conclusion

In short, Joséphin Péladan tried to define the art of his day in a manner that was quite rare for the time but is today exceedingly common. But because the curatorship of contemporary art did not come to be until much later, we should assume there to be certain differences between today’s curator and such isolated “proto-examples.” So as not to get lost listing every possible specific difference, let us look at a difference that does seem to be at the very heart of the phenomenon. Until at least the first decades of the twentieth century, roughly speaking, the situation in the art field as a whole was fundamentally different that it is today; that does not mean that certain segments weren’t already to a certain extent compatible with today’s curatorial practice, but others weren’t yet in tune with such practices. For example, at the time it was already possible to organize a large group exhibition of contemporary art in accord with one’s own concept; to acquire the agreement and participation of artists, and a circle of supporters and backers; and attract the clear interest of the public and media; yet in contrast with today’s art world, the institutionalization of such curatorial practices, which might allow them to happen regularly and widely, was completely absent. In the nineteenth century, the contemporary art exhibition was still very much in the domain of the market, and many years would pass before it became the preferred form for supporting contemporary art on the part of the big backers and commissioners, politics and capital, and the today ubiquitous but then nonexistent art institutions. Among other things, the (large group) exhibition of contemporary art was not yet understood as something that, in the ritualized setting of a museum or gallery, could create narratives, generate meanings, shape worldviews, beliefs, and values, and so potentially even influence society in line with the desires of those who commissioned it. For such large structural shifts to occur, it had to become clear that such an exhibition does not only show and sell contemporary art but can also do much more, especially in terms of constructing specific integral messages and communicating them such that the potential ideological implications go unnoticed.

Still, despite the institutional sector not being immediately ready to adopt ambitious proto-curators, it is hard to say that Péladan had no influence at all on the field of contemporary art curatorship. His practices and strategies came into curatorship mainly by indirect routes, mostly through the mediation of artists who in the early twentieth century increasingly cultivated a practice similar to Péladan’s. Unfortunately, we are only vaguely aware of this current, probably because serious thought about Péladan’s influence—even on such central, iconic twentieth-century artists as Kandinsky, Malevich, Hugo Ball, and Duchamp, and on such groups as the Vienna Secession, Futurists, Dadaists, and Surrealists—is establishing itself in the art-historical discourse slowly, timidly, and in bits and pieces. It seems that we do not wish to see the characteristic practices of the pioneers of contemporary art as linked to similar practices Péladan had employed quite strikingly not long before, to the great attention of both press and public.

Because these iconic artists’ influence on the development of the exhibiting of contemporary art—and the development of contemporary curatorship and curatorial practices—is sufficiently well known, I will not discuss it here. Instead, I would like to propose a more active scrutiny of Péladan’s influences on these artists in areas where I see a possible connection with contemporary curating. Here I propose three categories of influence, which may have operated separately or, even more often, as a whole, as an effective integrated work model.

First, we should note the importance of Péladan’s use of the exhibition medium as a distinctly independent means of expression that is able to tell its own story and so requires a specific kind of “dramaturgy and directing.” In this regard, the exhibition is not merely a passive juxtaposition of artworks; rather, it is simultaneously an interdisciplinary and intermedia platform, a “synaesthetic environment,” and an intensive media event. We can assume that these aspects were reflected in the pioneering exhibition projects of the key figures of early-twentieth-century art—although, given the scant research into the connections between them and Péladan, it is difficult to determine the exact nature and extent of this reflection.

Second, Péladan’s specific logic in constructing his own career in the art field seems to have been very influential: what is important here is the way he established and designed himself as a public persona with a clearly readable identity. Péladan—and we must not forget that he was himself an artist—actively tried to shape his own mythology, to turn anything connected with himself into an event, to develop his profile on different levels and through very different activities, and in a way to transform himself into an institution. While Péladan was certainly not the only one to do this, we need to consider more thoroughly his role in the evolution of the type of artist that came into its own in a real way in the decade before the First World War—the artist who forges his profile not only by creating artworks but through a variety of activities, including writing (among other things, manifestos), public performances, all sorts of organizing (of groups, events, and so forth), developing networks, a specific way of acting and dressing, unusual gestures, rituals, and the like.

And last of all, however unexpected as it may sound, the influence of Péladan’s worldview is also probably greater than it seems at first. I am thinking mainly of his specific view of art in general, its aims and potential. Here the key element is his distinct contribution in raising the status of art, which was based on his understanding of art as a medium for presenting spheres that are suprarational, and as an effective tool for improving the world. Accordingly, Péladan also raised the status of the artist, who with this sort of responsible, priestly mission was now suddenly in a different position than before, also vis-à-vis society. With this understanding of art, a great deal was now expected of the artist, and much more, too, was permitted him. In the twentieth century such views became increasingly established, also in the art field. Péladan’s contribution, however, was overlooked, mainly, I suspect, because his mystical explanations for these views, with their strange combination of Catholicism, elitism, conservatism, pomposity, and incoherence, were difficult for a wider audience to accept. But it is worth pointing out that in the early twentieth century, the leading figures of contemporary art themselves very often connected their work to mysticism, even to a mysticism that is sometimes surprisingly close to Péladan’s.21

Robert Jensen, Marketing Modernism in Fin-de-Siècle Europe (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994), 3.

This, of course, is a provisional term for these individuals, although of all the possible professions in the art field, that of the modern-day curator most closely fits their work. Certainly, they had little in common with either the traditional museum custodian or the private gallerist. In France we find a few interesting examples of “protocurators” even before Péladan. A very early one is Mammès-Claude Pahin de La Blancherie, who in the second half of the eighteenth century was especially appalled by the cruelty of the American slave trade and devoted himself to liberating art and science from the bonds of tradition. Among other activities connected with his ideological views, he also organized a few exhibitions. These were temporary art shows, produced and conceived by Pahin himself and presented in the rooms of his own salon, which operated with the help of important sponsors. One appealing characteristic of his exhibition practice was that his catalogues also listed works he wanted to exhibit but was unable to borrow for the show. These were marked by an asterisk. See Francis Haskell, The Ephemeral Museum: Old Master Paintings and the Rise of the Art Exhibition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 14-22.

Today the best-known curators normally have certain well-developed philosophical positions, on which their work is based and which they feel committed to—or at least very passionately defend. They present these views as part of both their personal and professional identities, use them to set themselves apart from other curators, actually “compete” with them against each other, and so forth. See, for instance, Beti Žerovc, “Charles Esche,”Život umjetnosti, vol. 37, no. 3 (2003): 60–65.

Mario Praz, The Romantic Agony (London: Oxford University Press, 1954), 316.

Philippe Jullian, The Symbolists (London: Phaidon, 1973), 26.

Edward Lucie-Smith, Symbolist Art (London: Thames & Hudson, 1972), 98–102.

Ibid., 109.

Joséphin Péladan, Der Androgyn (Munich: Georg Müller, 1924; originally published in French in 1891). The foreword to the German edition of Péladan’s novel series was written by August Strindberg.

Robert Pincus-Witten, Occult Symbolism in France: Joséphin Péladan and the Salons de la Rose-Croix (New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1976), 90. Despite the fact that the exhibitions were official events of the Rosicrucian Order, I propose viewing them as primarily Péladan’s affair in both their organization and content, which is how they have been treated by previous writers who have discussed them. I do not compare them with similar exhibitions put on by different artists’ associations at the time, since in the latter the groups’ dynamics, work, interests, and goals were, as a rule, explicitly in the foreground. Much original material connected with Péladan’s Rosicrucian Order and its exhibitions is available on the internet (e.g., through the electronic library Gallica), while in the work cited above, Pincus-Witten provides a precise description of the Order and the exhibitions in English.

Péladan’s obvious knack for promotion, including of course self-promotion, has been noted by earlier art historians, who compare him to the more famous Marinetti. Like the celebrated futurist after him, Péladan worked tirelessly to proclaim his positions and organize events, while at the same time drawing attention to himself. “Like Marinetti, Péladan seems to have been a compulsive exhibitionist, whose greatest artistic creation was his own personality” (Lucie-Smith, Symbolist Art, 109). In the history of contemporary art, Péladan may well be more important than we now imagine, among other reasons because of his potential influence on art-world figures such as Diaghilev, Marinetti, and others, who started appearing not long after him. Péladan, who was also very active in the areas of conceiving and organizing musical and theatrical events, is further connected with such figures by his desire to produce the most auratic events possible, where what was essential was not so much the chosen medium or art form but rather the ultimate effect of the whole, which had to be as magnificent as possible. Thus, a musical event or art exhibition would be “directed” very much like a theater production. Compare Beti Žerovc, “The Exhibition as Artwork, the Curator as Artist: A Comparison with Theatre,” Maska, vol. 25, no. 133/134 (Autumn 2010): 78–93. On the synaesthetic effects of the different artistic media at the Rosicrucian salons, and on Péladan’s extraordinary enthusiasm for Wagner, see Laurinda S. Dixon, “Art and Music at the Salons de la Rose-Croix,” in The Documented Image; Visions in Art History, eds. Gabriel P. Weisberg and Laurinda S. Dixon (New York: Syracuse, 1987), 165–186.

Gisèle Ollinger-Zinque, “The Belgian artists and the Rose-Croix,” in Simbolismo en Europa: Nestor en las Hesperides (Las Palmas de Gran Canaria: Centro Atlantico de Arte Moderna, 1990), 371.

Robert Pincus-Witten, Occult Symbolism in France, 104–106, 131. The strong connection between contemporary art exhibitions and the media, even in the nineteenth century, is evident in the fact that for this first salon, as many as two thousand invitations were sent to the press! In fact, of all the Rosicrucian salons, the first received the best response from the media; this was, I expect, due in part not only to the initial shock at such an extraordinary project, but also to the show itself, which in fact impressed many as a special kind of Gesamtkunstwerk. The salons that followed did not elicit such a response, and the last editions saw a decline in both the size of the shows and the quality of the artwork, as well as in the enthusiasm of sympathizers and financial backers and even in Péladan’s own determination and drive. All of this led to an increase in negative responses from the press. See Christophe Beaufils, Joséphin Péladan (1858−1918): Essai sur une maladie du lyrisme (Grenoble: J. Millon, 1993), 272–273, 300–301, 313–314, and elsewhere.

Beaufils, Joséphin Péladan, 225–235; Pincus-Witten, Occult Symbolism in France, 140–144.

The French symbolists who are best known today had no desire to participate in Péladan’s salons, although he did all he could to assemble as star-studded a group as possible (partly, I assume, because he was well aware of its promotional and social potential). Thus, he invited both Gustave Moreau and Pierre Puvis de Chavannes to show their work, but he did not receive their permission. He simply idolized Moreau, who, however, evidently had serious doubts about the Rosicrucian hocus-pocus. Even so, the painter sent his students to Péladan to be exhibited. Of the numerous French artists who showed work in his salons, not many are particularly famous today. The ones who do stand out somewhat are Charles Filiger, Alphonse Osbert, Alexandre Séon, Edmond Aman-Jean, Antoine Bourdelle, Georges Rouault, and Armand Point. Nor can we say that the group of artists that formed around Péladan’s salons was fully coherent in style. Especially in the first salon, several artists had distinctly post-impressionist tendencies; here we could put Count de la Rochefoucauld. As the years passed, the salons became more unified stylistically, though unfortunately with a drop-off in the better-quality artists, while the work of those such as Point, Osbert, and Séon came to be seen, in a way, as the most typically Rosicrucian style of art.

But even here he was not always successful, as we learn from an amusing anecdote. One of Péladan’s favorite painters was the Englishman Edward Burne-Jones, who was more than a little astonished by Péladan’s invitation to participate. He wrote about it to his colleague, the painter George Frederic Watts: “I don’t know about the Salon of the Rose-Cross—a funny high falutin sort of pamphlet has reached me—a letter asking me to exhibit there, but I feel suspicious of it … the pamphlet was disgracefully silly.” (Quentin Bell, A New and Noble School: The Pre-Raphaelites [London: Macdonald, 1982], 175).

Oskar Bätschmann, The Artist in the Modern World: The Conflict between Market and Self-Expression, (Cologne: DuMont Buchverlag, 1998), 9–10 et passim.

Pincus-Witten, Occult Symbolism in France, 211–216. Longer summaries of the rules can be found in Lucie-Smith, Symbolist Art, 111–112; and Jullian, The Symbolists, 227.

Lucie-Smith, Symbolist Art, 111–112.

Péladan’s similarity to certain modern-day curators can be seen as well in the incoherence of his ideas—he was incredibly enthusiastic about all sorts of things, including, unsurprisingly, things that were completely incompatible. For example, although he banned the portrait genre (with only rare exceptions), he exhibited grandiose portraits of himself, and although he was a devout Catholic and a defender of virtue and purity, he was also a devoted admirer of the Belgian painter and illustrator Félicien Rops, whose drawings and illustrations are often a very perverse kind of pornography. This was an artist and an art that sprang from completely different views, the very opposite of his own, but still Péladan desperately wanted him for his salons and so always found a way to explain his enthusiasm for the Belgian. For example: “I have seen some of his masterful etchings, of such an intense perversity that I, who am preparing the Treatise on Perversity, was enchanted by his extraordinary talent” (Ollinger-Zinque, “The Belgian artists and the Rose-Croix,” 370). The two men also engaged in a vast correspondence; Péladan wrote to Rops: “May the devil, your supposed master, keep for you the admiration of Catholic artists, to the greater confusion of Protestant pigs and bourgeois swine, Amen!” (ibid.). Rops, in fact, never did exhibit in Péladan’s salons, although he provided illustrations for a number of his novels.

Ollinger-Zinque, “The Belgian artists and the Rose-Croix,” 370.

On connections between Péladan and, for example, Duchamp (the two had many interests in common), see John F. Moffitt, Alchemist of the Avant-Garde: The Case of Marcel Duchamp (New York: SUNY Press, 2003), 27, 252; and James Housefield, “The Nineteenth-Century Renaissance and the Modern Facsimile: Leonardo da Vinci’s Notebooks, From Ravaisson-Mollien to Péladan and Duchamp,” in The Renaissance in the Nineteenth Century / Le 19e Siècle Renaissant, eds. Yannick Portebois and Nicholas Terpstra (Toronto: Centre for Reformation and Renaissance Studies Publications, Victoria University in the University of Toronto, 2003), 73−88, among others. When we consider what traces Péladan left on curatorship, it is essential to stress his potential structural influences. In the present article, therefore, I have largely disregarded his specific ideas, which can be so bombastic that they very quickly drown out everything else and take us in their own direction. Looking at these ideas, we soon find ourselves dealing with instantly obvious comparisons based mainly on content (for example, with Harald Szeemann’s body of work).

Category

Subject

This article (in a slightly different version) appeared previously in Slovene as “Josephin Peladan—protokurator?,” Dialogi 43, nos. 5–6 (2007): 26–35. It has been translated to English by Rawley Grau.