Chapter 1: The National Museum

This is a file published in 2012 by WikiLeaks. It forms part of WikiLeaks’s Syria files database.1 The file is called “316787_Vision Presentation—Oct 30 2010 Eng.pptx,” in PowerPoint format, dated October 2010.2 It details Syrian First Lady Asma al-Assad’s plans for the future of Syria’s museums. Her foundation aims to establish a network of museums to promote Syria’s economic and social development and strengthen national identity and cultural pride.3 The French Louvre is listed as a partner in developing this plan.4 Both the Louvre and the Guggenheim Bilbao are named as role models for a redesigned National Museum in Damascus.

A conference is planned to unveil the winner of an international competition for the design of this National Museum in April 2011.

However, three weeks prior to this date, twenty protesters were “reportedly killed as 100,000 people marched in the city of Daraa.”5 By then, invitations for the conference had already been issued to a host of prominent speakers, including the directors of the Louvre and the British Museum. On April 28, 2011, Art Newspaper reports that the conference has been cancelled due to street protests.6 The winner of the architectural competition for the National Museum has never been announced.

Chapter 2: Never Again

To build a nation, Benedict Anderson suggested that there should be print capitalism7 and a museum to narrate a nation’s history and design its identity.8 Today—instead of print—there is data capitalism and a lot of museums. To build a museum, a nation is not necessary. But if nations are a way to organize time and space, so is the museum. And as times and spaces change, so do museum spaces.

The image above shows the municipal art gallery of Diyarbakir in Turkey. From June to September 2014, it hosts a show on genocide and its consequences, called “Never Again! Apology and Coming to Terms with the Past.” Its poster shows former prime minister of West Germany Willy Brandt on his knees in front of the Warsaw ghetto memorial.

In September 2014, this museum became a refugee camp. It did not represent a nation, but instead sheltered people fleeing from national disintegrations.

After the Islamic State (IS) militia crossed and effectively abolished parts of the border between Syria and Iraq in August 2014,9 between fifty thousand and one hundred thousand Yezidi refugees escaped the region of Shengal in northern Iraq. Most of them had trekked on foot across Mt. Shengal, assisted by Kurdish rebel groups, who had opened a safety corridor. While the majority stayed in refugee camps in Rojava, northern Syria, and several camps in northern Iraq, many refugees crossed into Turkey’s Kurdish regions, where they were welcomed with amazing hospitality. The city of Diyarbakir opened its municipal gallery as an emergency shelter.

Once settled on mats within the gallery space, many refugees started asking for SIM cards to try to reach missing family members by cell phone.

This is the desk of the curator, left empty.10

Chapter 3: Conditions of Possibility

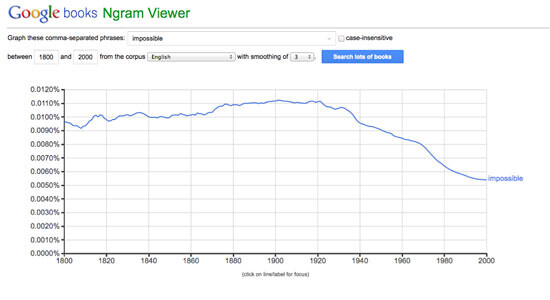

According to the Google N-gram viewer,11 the usage of the word “impossible” has steeply dropped since around the mid-twentieth century. But what does this tell us? Does it mean that fewer and fewer things are impossible? Does this mean that impossibility “as such” is in historical decline? Perhaps it just means that the conditions for possibilities as such are subject to change over time? Are both the possible and the impossible defined by historical and external conditions?

According to Immanuel Kant, time and space are necessary conditions to perceive or understand anything. Without time and space, knowledge, experience, and vision cannot unfold. Kant calls this perspective “criticism.” With this in mind, what kind of time and space is necessary for contemporary art to become manifest? Or rather: What does criticism about contemporary art say about time and space today?

To brutally summarize a lot of scholarly texts: contemporary art is made possible by neoliberal capital plus the internet, biennials, art fairs, parallel pop-up histories, growing income inequality. Let’s add asymmetric warfare—as one of the reasons for the vast redistribution of wealth—real estate speculation, tax evasion, money laundering, and deregulated financial markets to this list.

To paraphrase philosopher Peter Osborne’s illuminating insights on this topic: contemporary art shows us the lack of a (global) time and space. Moreover, it projects a fictional unity onto a variety of different ideas of time and space, thus providing a common surface where there is none.12

Contemporary art thus becomes a proxy for the global commons, for the lack of any common ground, temporality, or space.

It is defined by a proliferation of locations, and a lack of accountability. It works by way of major real estate operations transforming cities worldwide as they reorganize urban space. It is even a space of civil wars that trigger art market booms a decade or so later through the redistribution of wealth by warfare. It takes place on servers and by means of fiber optic infrastructure, and whenever public debt miraculously transforms into private wealth. Contemporary art happens when taxpayers are deluded into believing they are bailing out other sovereign states when in fact they are subsidizing international banks that thus get compensated for pushing high-risk debt onto vulnerable nations.13 Or when this or that regime decides it needs the PR equivalent of a nip and tuck procedure.

But contemporary art also creates new physical spaces that bypass national sovereignty.

Let me give you a contemporary example: freeport art storage.

This is the mother of all freeport art storage spaces: Geneva freeport, a tax-free zone in Geneva that includes parts of an old freight station and an industrial storage building. The free-trade zone takes up the backyard and the fourth floor of the old storage building, so that different jurisdictions run through one and the same building, as the other floors are set outside the freeport zone. A new art storage space was opened last year. Up until only a few years ago, the freeport wasn’t even officially considered part of Switzerland.

This building is rumored to house thousands of Picassos, but no one knows an exact number since documentation is rather opaque. There is little doubt though that its contents could compete with any very large museum.14

Let’s assume that this is one of the most important art spaces in the world right now. It is not only not public, but it is also sitting inside a very interesting geography.

From a legal standpoint, freeport art storage spaces are somewhat extraterritorial. Some are located in the transit zones of airports or in tax-free zones. Keller Easterling describes the free zone as a “fenced enclave for warehousing.”15 It has now become a primary organ of global urbanism copied and pasted to locations worldwide. It is an example of “extrastatecraft,” as Easterling terms it, within a “mongrel form of exception” beyond the laws of the nation-state. In this deregulatory state of exemption, corporations are privileged at the expense of common citizens, “investors” replace taxpayers, and modules supplant buildings:

[Freeports’] attractions are similar to those offered by offshore financial centres: security and confidentiality, not much scrutiny … and an array of tax advantages … Goods in freeports are technically in transit, even if in reality the ports are used more and more as permanent homes for accumulated wealth.16

The freeport is thus a zone for permanent transit.

Although it is fixed, does the freeport also define perpetual ephemerality? Is it simply an extraterritorial zone, or is it also a rogue sector carefully settled for financial profitability17?

The freeport contains multiple contradictions: it is a zone of terminal impermanence; it is also a zone of legalized extralegality maintained by nation-states trying to emulate failed states as closely as possible by selectively losing control. Thomas Elsaesser once used the term “constructive instability” to describe the aerodynamic properties of fighter jets that gain decisive advantages by navigating at the brink of system failure.18 They would more or less “fall” or “fail” in the desired direction. This constructive instability is implemented within nation-states by incorporating zones where they “fail” on purpose. Switzerland, for example, contains “245 open customs warehouses,”19 enclosing zones of legal and administrative exception. Are this state and others a container for different types of jurisdictions that get applied, or rather do not get applied, in relation to the wealth of corporations or individuals? Does this kind of state become a package for opportunistic statelessness? As Elsaesser pointed out, his whole idea of “constructive instability” originated with a discussion of Swiss artists Fischli and Weiss’s work Der Lauf der Dinge (1987). Here all sorts of things are knocked off balance in celebratory collapse. The film’s glorious motto is: “Am schönsten ist das Gleichgewicht, kurz bevor’s zusammenbricht” (Balance is most beautiful just at the point when it is about to collapse).

Among many other things, freeports also become a zone for duty-free art, a zone where control and failure are calibrated according to “constructive instability” so that things cheerfully hang in a permanently frozen failing balance.

Chapter 4: Duty-Free Art

Huge art storage spaces are being created worldwide in what could essentially be called a luxury no man’s land, tax havens where artworks are shuffled around from one storage room to another once they get traded. This is also one of the prime spaces for contemporary art: an offshore or extraterritorial museum. In September 2014, Luxembourg opened its own freeport. The country is not alone in trying to replicate the success of the Geneva freeport: “A freeport that opened at Changi Airport in Singapore in 2010 is already close to full. Monaco has one, too. A planned ‘freeport of culture’ in Beijing would be the world’s largest art-storage facility.”20 A major player in setting up many of these facilities is the art handling company Natural Le Coultre, run by Swiss national Yves Bouvier.

Freeport art storage facilities are secret museums.

Their spatial conditions are reflected in their designs.

In contrast to the rather perfunctory Swiss facility, designers stepped up their game at the freeport art storage facility in Singapore:

Designed by Swiss architects, Swiss engineers and Swiss security experts, the 270,000-square-foot facility is part bunker, part gallery. Unlike the free-port facilities in Switzerland, which are staid yet secure warehouses, the Singapore FreePort sought to combine security and style. The lobby, showrooms and furniture were designed by contemporary designers Ron Arad and Johanna Grawunder. A gigantic arcing sculpture by Mr. Arad, titled “Cage sans Frontières,” (Cage Without Borders) spans the entire lobby. Paintings that line the exposed concrete walls lend the facility the air of a gallery. Private rooms and vaults, barricaded by seven-ton doors, line the corridors. Near the lobby, private galleries give collectors a chance to view or show potential buyers their art under museum-quality spotlights. A planned second phase will double the size of the facility to 538,000 square feet. Collectors are picked up by FreePort staff at their plane and whisked by limousine, any time of day or night, to the facility. If the client is packing valuables, an armed escort will be provided.21

The title “Cage Without Borders” has a double meaning. It not only means that the cage has no limits, but also that the prison is now everywhere, in an extrastatecraft art withdrawal facility that seeps through the cracks of national sovereignty and establishes its own logistic network. In this ubiquitous prison, rules still apply, though it might be difficult to specify exactly which ones, to whom or what they apply, and how they are implemented. Whatever they are, their grip seems to considerably loosen in inverse proportion to the value of the assets in question. But this construction is not only a device realized in one particular location in 3-D space. It is also basically a stack of juridical, logistical, economic, and data-based operations, a pile of platforms mediating between clouds and users via state laws, communication protocols, corporate standards, etc., that interconnect not only via fiber-optic connections but aviation routes as well.22

Freeport art storage is to this “stack” as the national museum traditionally was to the nation. It sits in between countries in pockets of superimposing sovereignties where national jurisdiction has either voluntarily retreated or been demolished. If biennials, art fairs, 3-D renderings of gentrified real estate, starchitect museums decorating various regimes, etc., are the corporate surfaces of these areas, the secret museums are their dark web, their Silk Road into which things disappear, as into an abyss of withdrawal.23

Think of the artworks and their movement. They travel inside a network of tax-free zones and also inside the storage spaces themselves. Perhaps as they do, they do not ever get uncrated. They move from one storage room to the next without being seen. They stay inside boxes and travel outside national territories with a minimum of tracking or registration, like insurgents, drugs, derivative financial products, and other so-called investment vehicles. For all we know, the crates could even be empty. It is a museum of the internet era, but a museum of the dark net, where movement is obscured and data-space is clouded.

Movements of a very different kind are detailed in WikiLeaks’s Syria files.

——- Original Message ——-

From: xy@sinan-archiculture.com

To: xy@mopa.gov.sy

Sent: Wednesday, July 07, 2010 4:06 PM

Subject: Fw: Flight itenary OMA staff ***AMENDMENT*****Dear Mr. Azzam,

This is to confirm the arrival of Mr. Rem Koolhaas and his personal assistant Mr. Stephan Petermann on this coming Monday July 12th. We need visa for them as we spoke before (both are Dutch). Their passport photos are attached. They are arriving separately and at different times. Mr. Koolhaas coming from China through Dubai on Emirates airlines (arriving in Damascus at 4:25 PM), while Mr. Stephan Petermann is coming from Vienna on Austrian airlines (arriving in Damascus before Mr. Koolhaas at 3:00 PM).They are staying at the Art House or at the Four Seasons hotel until their departure on Thursday (at 4:00 pm).24

WikiLeaks’s Syria database comprises around 2.5 million emails from 680 domains, yet the authenticity of these documents was not verified by WikiLeaks. It can be verified, however, that the PR company Brown Lloyd James was involved in trying to enhance the image of the Assad family.25 In early 2011, shortly before the start of the Syrian civil war, a Vogue story, presciently photographed by war photographer James Nachtwey, portrays Asma al-Assad as the “Rose of the Desert,” a modernizer and patron of culture.26

In February 2012, one year into the war, Anonymous and affiliated organizations hacked into the email server of the Syrian Ministry of Presidential Affairs, in solidarity with Syrian bloggers, protesters, and activists.27 The inboxes of seventy-eight of Assad’s aides and advisers were accessed. Apparently, some used the same password: “12345.”28 The leaked emails included correspondence—mostly through intermediaries—between Mansour Azzam, the Minister of Presidential Affairs, and the studios of Rem Koolhaas (OMA), Richard Rogers, and Herzog and de Meuron regarding various issues.29 To paraphrase the content of some emails: Rogers and Koolhaas were being invited to speak in Damascus and, with Koolhaas, these visits extended to project discussions including the National Parliament.30 Herzog de Meuron offered a complimentary concept design proposal for the Al-Assad House for Culture in Aleppo, and expressed interest in the selection process for the parliament project.31 A lot of this correspondence is really just gossip about the studios by way of intermediaries. There is also lots of spam. No communication with any of the studios is documented after the end of November 2010. With protests starting in January 2011, a full-blown uprising began in Syria by the end of March of that year. All conversations and negotiations between officials and architects seem to have stopped as scrutiny of the Assad regime increased in the buildup to actual hostilities. The authenticity of none of these documents32 could be confirmed independently, so for the time being, their status is that of unmoored sets of data, which may or may not have anything to do with their presumed authors and receivers.33 But they most definitely are sets of data, hosted by WikiLeaks servers that can be described in terms of their circulation regardless of presumed provenance and authorship.34

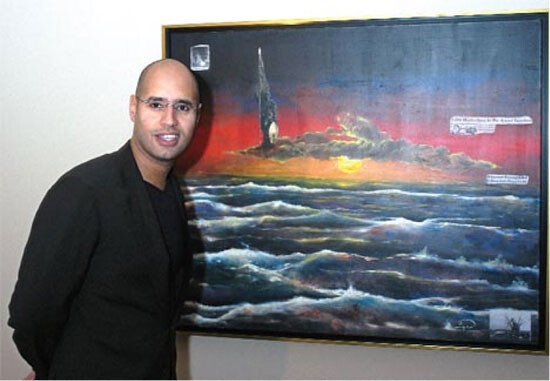

Above is Saif al-Islam Gaddafi’s painting, War (2001). Saif is the son of the late head of Libya, Muammar Gaddafi and was a political figure in Libya prior to his father’s deposition by rebel forces backed by NATO airstrikes in 2011. This painting was exhibited as part of a show called “The Desert is not Silent” in London in 2002.

War depicts NATO’s bombing of Yugoslavia in 1999.

The artist writes: “A civil war broke out in Kosovo, which shattered the picture and its theme. The sea unleashed itself, anger fell from the sky, which came up against a stream of blood.”35

Saif al-Islam said in a statement at the time: “Not only do we buy weapons and sell gas and oil, but we have culture, art and history.”36

In September 2010, OMA expresses the desire to work in Syria.37 A subsequent email from Sinan Ali Hassan—a local architect who acts as an intermediary—to Mansour Azzam flaunts the advantages of such a collaboration: “Rem was the previous supervisor and boss of Zaha Hadid in addition to the fact that he is considered to be more important (if not much more important) than Lord Richard Rogers, in terms of celebrity and professional status.”38

From the conversation between OMA and Sinan Ali Hassan, it becomes clear that OMA’s proposal might be based on a project realized in Libya previously: “This would be a similar scope to the Libyan Sahara vision we showed you, and the one that Rem discussed with the President.”39

In an interview in June 2010, Koolhaas states that people close to Saif al-Islam Gaddafi approached him.40] son there who want to pull the country toward Europe’” →.] At the time, he is widely seen as a reformer. OMA’s project in Libya revolves around preservation and is exhibited at the Venice Biennale.41 The project is later mentioned as a possible precedent for a project proposal for the desert region around Palmyra, Syria. Since the uprising in early 2011, this area has been deeply affected by the ensuing civil war.

At present, the International Criminal court has requested Saif Gaddafi’s extradition from Libya, where he remains imprisoned.42

Chapter 5: A Dream

WARNING: THIS IS THE ONLY FICTIONAL CHAPTER IN THIS TALK

To come back to the original question: What happened to time and space? Why are they broken and disjointed? Why is space shattered into container-like franchising modules, dark webs, civil wars, and tax havens replicating all over the world?

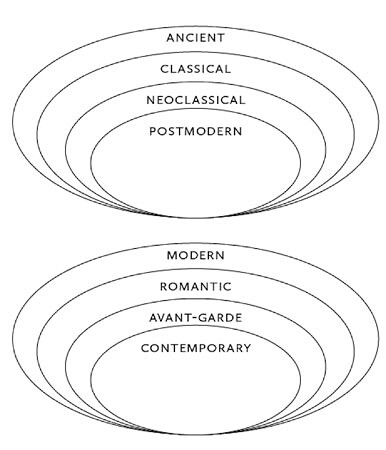

With these thoughts in mind, I fell asleep and started dreaming … and my dream was pretty strange. I dreamt about some diagrams in one of Peter Osborne’s recent texts.

They describe a genealogy of contemporary art; I wasn’t focusing on their content, but instead on their form. The first thing I noticed was that the succession of concentric circles seemed to indicate a dent, or a dimple, in any case, a 3-D cavity. But why would time and space start sagging, so to speak? Could there be an issue with gravity? Maybe a micro–black hole could cause these circles to curve? But then again, it is much more likely that something else caused this dimple.

Suddenly, I found the answer to the question. I started losing gravity and flying up towards space. Peter Osborne was floating around there too, and with an unlikely Texas accent, he pointed down and showed me this sight.

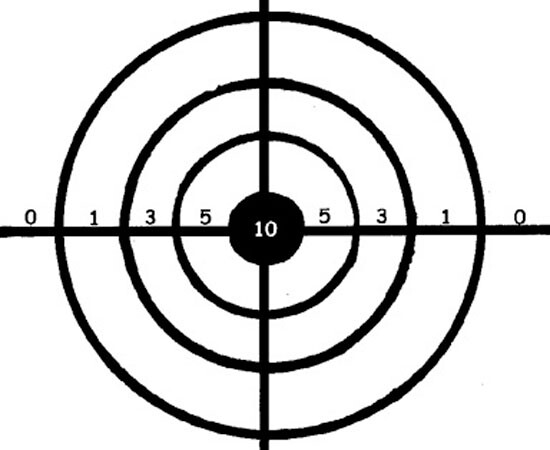

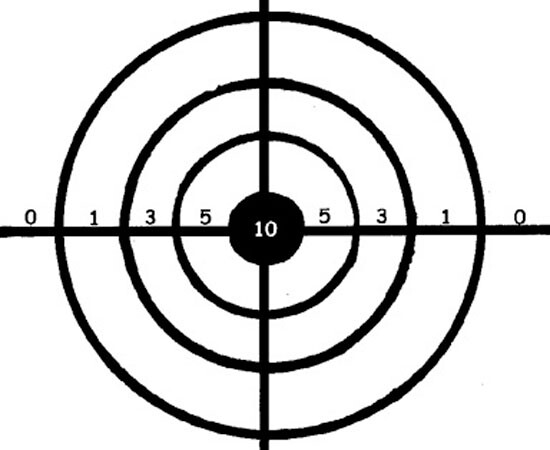

Crosshairs aiming at a target.

Seen from above, Peter’s diagram transformed into a sight.

If you look at it from above, the slight cavity vanishes. It becomes a flat screen. From here on, people just ended up seeing the genealogy of contemporary art in Peter’s diagrams instead of a depression indicating that the target had been hit already and that a gaping crater had opened at the site of impact.

Seen from above, the genealogy of contemporary art was acting as a proxy or a screen: a sight to cover the site of impact.

Behind his astronaut’s visor, Peter croaked:

This is the role of contemporary art. It is a proxy, a stand-in. It is projected onto a site of impact, after time and space have been shattered into a disjunctive unity—and proceed to collapse into rainbow-colored stacks designed by starchitects.

Contemporary art is a kind of layer or proxy which pretends that everything is still ok, while people are reeling from the effects of shock policies, shock and awe campaigns, reality TV, power cuts, any other form of cuts, cat GIFs, tear gas—all of which are all completely dismantling and rewiring the sensory apparatus and potentially also human faculties of reasoning and understanding by causing a state of shock and confusion, of permanent hyperactive depression.

You don’t know what’s going on behind the doors of the freeport storage rooms either, do you? Let me tell you what’s happening in there: time and space are smashed and rearranged into little pieces like in a freak particle accelerator, and the result is the cage without borders called contemporary art today.

—AND THIS IS WHERE THE FICTIONAL PART ABRUPTLY ENDS—

I woke in shock and found myself reading this .pdf document aloud.

Chapter 6: And Now to Justin Bieber

This is the Twitter feed of E! Online on May 4, 2013, which has someone posing as Bieber triumphantly blurting out: “I’m a gay.”

As you can see, the Syrian Electronic Army (SEA) has hacked the Twitter account.

Who is the SEA? It is a group of pro-Assad regime hackers. They also hacked Le Monde in France a few weeks ago. Previously, the SEA had commandeered: the websites of the New York Times, the Washington Post, and the recruitment division of the US Marine Corps. The group also hacked the Twitter feed of the Associated Press and sent out a false report about a bombing at the White House.43

The above diagram shows the consequences of this tweet on Wall Street. In three minutes, the “fake tweet erased $136 billion in equity market value.”44

Anonymous Syria and its multiple allies had hacked the Syrian Electronic Army and dumped coordinates of alleged members onto the dark web.45

The data-space of Syria is embattled, hacked, fragmented. Moreover, it extends from the AP to Wall Street to Russian and Australian servers, as well as to the Twitter accounts of a celebrity magazine.

It extends to WikiLeaks’s servers, where the Syria files are hosted, and which had to move around quite a lot previously, being ousted from Amazon in 2010.

It was once rumored that WikiLeaks tried to move its servers to an offshore location, an exterritorial former oil platform called Sealand.46 This would in fact have replicated the freeport scenario from a different angle.

But to ask a more general question: How does the internet, or more precisely networked operations between different databases, affect the physical construction of museums—or the impossibility thereof?

Chapter 7: An Email Sent From Switzerland and its Reply

From: Hito Steyerl mailto:xy [at] protonmail.ch

Sent: Tuesday, February 17, 2015 8:05 PM

To: Office Reception

Subject: Request for confirmation of authenticity

Dear Sirs,

I would like to kindly ask you to confirm the authenticity of various email communications between OMA/AMO and Syrian government officials and intermediaries published by Wikileaks as part of their “Syria files” in 2012.

I am a Berlin-based filmmaker and writer working on a lecture about the transformations of national museums under conditions of civil war, both in data- and 3D physical space.

There is no intent to scandalize the communication between OMA and the Syrian Ministry of Presidential Affairs. The intent is to ask how both internet communication and the (near-) collapse of some nations states affect the planning of contemporary museum spaces.

In this context it would be interesting to know more about the circumstances that led to the end of project discussions in Syria. I am sure that your office had its reasons for this and it would be great to be able to include these in the discussion.

Pls find below a list of links I plan on quoting.

Best regards,

Hito Steyerl

https://wikileaks.org/syria-files/docs/2089311_urgent.html

https://wikileaks.org/syria-files/docs/2092135_very-important.html

https://wikileaks.org/syria-files/docs/2091860_fwd-.html

http://bit.ly/18jZeWr

Sent from ProtonMail, encrypted email based in Switzerland.

RE: Request for confirmation of authenticity

From: Jeremy Higginbotham

To: Hito Steyerl xy@protonmail.ch

CC: Legal xy@oma.com, xy xy@oma.com

At 26/02/2015 7:13 am

Dear Hito Steyerl,

Thank you for your email. We are not able to confirm the authenticity of the documents linked below.

However, we wish you good luck with your work.

Best regards,

Jeremy Higginbotham

Head of Public Affairs

OMA

(contact address redacted)

After the Edward Snowden leaks, I started using ProtonMail, an initiative by Cern researchers, who are graciously providing a free encrypted email platform. This is how they decribe their project, using the map of Switzerland:

All information on the ProtonMail servers is stored under the jurisdiction of the Cantonal Court of Geneva, taking advantage of the privacy laws of Switzerland and the Canton.

But OMA/AMO’s friendly response is not stored in a freeport, it is just stored under “regular” Swiss jurisdiction in a former military command center deep inside the Swiss alps.47 This is the jurisdiction and encryption I use to try to make any potential government interference with some of my data just a tiny bit more cumbersome. I am in fact taking advantage of legal protections that have enabled tax evasion and money laundering through Swiss banks and other facilities on an astounding scale.48 On the other hand, the mere usage of privacy-related web tools flags users for NSA scrutiny, thus effectively reversing its desired effect.49 The screen of anonymity turns out to be a paradoxical device.

The ambiguous effect of policies destined to increase anonymity also figures into a different level of freeport activity.

On February 25, 2015, Monaco prosecutors arrested Yves Bouvier—the owner of Natural Le Coultre, the company involved with the Luxemburg, Geneva, and Singapore freeports—for suspected art fraud: “The investigation is believed to centre on inflating prices in very big art transactions in which Bouvier was an intermediary.”50 Bouvier allegedly tookadvantage of the fact that most artworks held in freeports are owned by what are called “sociétés écran” (literally “screen companies”). Since transactions were made through these anonymous proxies, buyer and seller were not able to communicate and control the amount of commission fees charged. The screen that was supposed to provide anonymity for owners may also have worked against them. Invisibility is a screen that sometimes works both ways—through not always. It works in favor of whoever is controlling the screen.

Chapter 8: Shooting at Clocks—The Public Museum

To build a nation, Benedict Anderson suggested there should be print capitalism and a museum. Nowadays, it is not impossible to build a museum without a nation.

We can even look at it more generally and see both nations and museums as just another way to organize time and space, in this case, by smashing them to pieces.

But aren’t time and space smashed whenever a new paradigm for a museum is created? This indeed happened in France’s July Revolution of 1830, of which Walter Benjamin tells a story.51 Revolutionaries were shooting at clocks. They had previously also overturned the calendar, renaming months and changing their duration.

And this is the period when the Louvre was stormed yet again—as during every major Paris uprising in the nineteenth century. The prototype for a public museum was created when time and space were smashed and welded anew. The Louvre was created by being stormed. It was stormed in 1792 during the French Revolution and turned from a feudal collection of spoils—a period version of freeport art storage spaces—into a public art museum, presumably the first in the world, introducing a model of national culture. Afterwards, it turned into the cultural flagship of a colonial empire that tried to authoritatively seed that culture elsewhere, before more recently going into the business of trying to create franchises in feudal states, dictatorships, and combinations thereof.

But the current National Museum of Syria is of a different order. Contrary to plans inspired by the “Bilbao effect,” the museum is hosted online, on countless servers in multiple locations.

As Jon Rich and Ali Shamseddine have noted, it is a collection of online videos—of documents and records of innumerable killings, atrocities, and attacks that remain widely unseen.52 This is the de facto National Museum of Syria, not a Louvre franchise acquired by an Assad foundation. This accidental archive of videos and other documents is made in different genres and styles, showing people digging through rubble, or Twitter-accelerated decapitations in HD. It shows aerial attacks from below, not above. The documents and records produced on the ground end up on a variety of servers worldwide. They are available—in theory—on any screen, except in the locations where they were made, where the act of uploading something to YouTube can get people killed. This spatiotemporal inversion is almost like a reversal of the freeport aggregate art collections.

But the entirety of this archive is not adapted to human perception, or at least not to individual perception. Like all large-scale databases—including WikiLeaks’ Syria files—it takes the form of a trove of information without (or with very little) narrative, substantiation, or interpretation. It may be partly visible to the public, but not necessarily entirely intelligible. It remains partly inaccessible, not by means of exclusion, but because it overwhelms the perceptual capacity and attention span of any single individual.53

Chapter 9: Autonomy

Let’s go back to the examples at the beginning: the freeport art storage spaces, and the municipal gallery of Diyarbakır, which had become a refugee camp. One space withdraws artworks from the world by hoarding them, while the other basically sheltered the escapees of collapsing states. How and where can art be shown publicly, in physical 3-D space, without endangering its authors, while taking into account the breathtaking spatial and temporal changes expressed by these two examples? What form could a new model of the public museum take, and how would the notion of the “public” itself change radically in the process of thinking though this?

Let’s think back to the freeport art storage spaces and their stock of duty-free art. My suggestion is not to shun or belittle this proposition, but to push it even further.

The idea of duty-free art has one major advantage over the nation-state cultural model: duty-free art ought to have no duty—no duty to perform, to represent, to teach, to embody value. It should not be indebted to anyone, nor serve a cause or a master, nor be a means to anything. Duty-free art should not be a means to represent a culture, a nation, money, or anything else. Even the duty-free art in the freeport storage spaces is not duty free. It is only tax-free. It has the duty of being an asset.

Seen like this, duty-free art is essentially what traditional autonomous art might have been, had it not been elitist and oblivious to its own conditions of production.54

But duty-free art is more than a reissue of the old idea of autonomous art. It also transforms the meaning of the battered term “artistic autonomy.” Autonomous art under current temporal and spatial circumstances needs to take these very spatial and temporal conditions into consideration. Art’s conditions of possibility are no longer just the elitist “ivory tower,” but also the dictator’s contemporary art foundation, the oligarch’s or weapons manufacturer’s tax-evasion scheme, the hedge fund’s trophy,55 the art student’s debt bondage, leaked troves of data, aggregate spam, and the product of huge amounts of unpaid “voluntary” labor—all of which results in art’s accumulation in freeport storage spaces and its physical destruction in zones of war or accelerated privatization. Autonomous art within this context could try to understand political autonomy as an experiment in building alternatives to a nation-state model that continues to proclaim national culture while simultaneously practicing “constructive instability” by including gated communities for high-net-worth individuals, much like microversions of failed states. To come back to the example of Switzerland: this country is so pervaded by extraterritorial enclaves with downsized regulations that it could be more precisely defined as a x-percent rogue entity within a solid watch industry. But extrastatecraft can also be defined as political autonomy under completely different circumstances and with very different results, as recent experiments in autonomy from Hong Kong to Rojava have demonstrated.

But autonomous art could even be art set free both from its authors and owners. Remember the disclaimer by OMA? Now imagine every art work in freeports to be certified by this text: “I am not able to confirm the authenticity of this artwork.”

This is the Cultural Center in Suruç, Turkey. It is across the border from the city of Kobanê, the administrative center of the autonomous canton of the same name, which itself is located in the Rojava region of northern Syria. It is not a coincidence that the autonomous entities in Rojava are called cantons: they have been modeled after Swiss cantons, to emphasize the role that basic democracy played in initially establishing them.56

After the attack on the Kobanê canton by fighters from the so-called IS in September 2014, the Cultural Center was temporarily turned into another refugee camp, hosting several hundred people who fled from the besieged region around Kobanê. One of the refugees watched circling bombers through binoculars as the cultural workers and I discussed the role of culture and art.

But why am I showing you this?

Remember the top-down view of contemporary art?

In my dream—and perhaps also in reality—contemporary art was a layer that served to screen out the smashing of time and space on the ground. It served to project a disjunctive unity onto a geography marked by systems constructively “failing” to increase profitability, nation-states engulfed in civil war, fragmented time, and vast and major inequality. But a screen has two sides and potentially very different functions. It can decrease but also enhance visibility, protect and reveal, project and record, expose and conceal.

And now please edit this image: it shows the same situation from below, from under the screen.

It points very literally at a bottom-up model from a ground zero where time and space, and in some cases borders and nation-states, are smashed, as during the time when the first public museum was founded, creating not only junk space—a term coined by Rem Koolhaas that deeply influenced my work—but also junk time.57

When we look at this screen from above, we see a model of contemporary art, which has created the secret museum as one of its most important spaces, a model of terminal impermanence, of privacy and concealment, of constructive instability.

If we only knew what the guy with the binoculars sees from below, we might see its future public counterpart.

See →.

The PowerPoint file is attached to an email sent to the Ministry of Presidential Affairs with the subject line “Presentation on the New Vision for the Syrian Museums and Heritage Sites,” Oct. 30, 2010, Email-ID 2089122 →.

In the foundation’s own words: “Under the patronage of The First Lady, Asma Al-Assad, the Syrian Government is launching a cultural initiative of exceptional ambition—the transformation of its museums and the conservation of its heritage sites. To celebrate and inform this initiative, Cultural Landscapes 2011, a new annual forum, will bring together an international assembly of thought leaders and experts from the worlds of heritage, contemporary culture, academia and business. This inaugural edition will take the Syrian experience as a starting point for a discussion global in reach and conclusion,” Feb. 7, 2011, Email-ID 765252 (see attachment entitled “About Cultural Landscapes”) →.

However, on June 26, 2011, partner museums call for a dismantling of the initiative’s institutional framework, the Syria Heritage Foundation. Earlier that month, the Financial Times reported that the organization had suspended operations. See Lina Saigol, “First lady struggles to live up to promises,” Financial Times, June 9, 2011 →.

Peter Aspden, “The walls of ignorance,” Financial Times, June 9, 2012 →.

Anna Somers Cocks, “Syria turmoil kills Mrs Al-Assad’s forum,” The Art Newspaper, Apr. 28, 2011 →.

Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, revised and extended ed. (London: Verso, 1991), 224.

Anderson, “Census, Map, Museum,” excerpt from Imagined Communities, available at →.

The exodus of Yazidis from Shengal is described in Liz Sly, “Exodus from the mountain: Yazidis flood into Iraq following U.S. airstrikes,” Washington Post, Aug. 10, 2014 →.

His name is Baris Seyitvan.

Wikipedia: “The Google ‘Ngram’ Viewer is an online viewer, initially based on Google Books, that charts frequencies of any word or short sentence using yearly count of n-grams found in the sources printed since 1800 up to 2012 in any of the following eight languages: American English, British English, French, German, Spanish, Russian, Hebrew, and Chinese” →.

Osborne argues that contemporary art expresses the “disjunctive unity of present times … As a historical concept, the contemporary thus involves a projection of unity onto the differential totality of the times of human lives …” Peter Osborne, Anywhere or Not At All: Philosophy of Contemporary Art (London: Verso, 2013), 22.

As in the case of the relation between Germany (or EU-taxpayers) and Greece. Eighty-nine percent of the so-called bailout funds have gone to international banks. Only the remaining 11 percent has reached the Greek national budget. Even if only a fraction of this money ends up at auction, how would auctions nowadays fare without the constant subsidies from public funds that mysteriously end up as private assets?

“Suffice it to say, there is wide belief among art dealers, advisers and insurers that there is enough art tucked away here to create one of the world’s great museums.” David Segal, “Swiss Freeports Are Home for a Growing Treasury of Art,” New York Times, July 21, 2012 →.

Keller Easterling, Extrastatecraft: The Power of Infrastructure Space (London: Verso, 2014).

“Freeports: Über-warehouses for the ultra-rich,” The Economist, Nov. 23, 2013 →.

Marie Maurisse, “La «caverne d’Ali Baba» de Genève, plus grand port franc du monde, ignore la crise,” Le Figaro, Sept. 20, 2014: “Selon un document confidentiel, le port franc de Genève dans son ensemble générerait chaque année pas moins de 300 millions de francs de retombées économiques sur le canton“ (According to a confidential document, Geneva freeport in total would generate no less than 300 million Swiss francs of revenue for the canton).

Thomas Elsaesser, “‘Constructive instability’, or: The life of things as the cinema’s afterlife?” 2008, 19f. The texts manifold implications for contemorary political thought and its relation to managed collapse cannot be underestimated, in relation to its discussion of technology but also political usage: “Its engineering provenance has been overlaid by a neo-con political usage, for instance, by Condoleezza Rice when she called the deaths among the civilian population and the resulting chaos during the Lebanon-Israel war in the summer of 2006 the consequence of ‘constructive instability’” →.

Cynthia O’Murchu, “Swiss businessman arrested in art market probe,” Financial Times, Feb. 26, 2015 →.

“Freeports,” The Economist.

Cris Prystay, “Singapore Bling,” Wall Street Journal, May 21, 2010 →.

Benjamin Bratton, “On the Nomos of the Cloud: The Stack, Deep Address, Integral Geography,” Nov. 2011: “The Stack, the megastructure, can be understood as a confluence of interoperable standards-based complex material-information system of systems, organized according to a vertical section, topographic model of layers and protocols. The Stack is a standardized universal section. The Stack, as we encounter it and as I prototype it, is composed equally of social, human and ‘analog’ layers (chthonic energy sources, gestures, affects, user-actants, interfaces, cities and streets, rooms and buildings, organic and inorganic envelopes) and informational, non-human computational and ‘digital’ layers (multiplexed fiber optic cables, datacenters, databases, data standards and protocols, urban-scale networks, embedded systems, universal addressing tables). Its hard and soft systems intermingle and swap phase states, some becoming ‘harder’ or ‘softer’ according to occult conditions. (Serres, hard soft). As a social cybernetics, The Stack that we know and design composes both equilibrium and emergence, one oscillating into the other in indecipherable and unaccountable rhythm, territorializing and de-territorializing the same component for diagonal purposes” →.

An extremely intelligent remark from an audience member in Moscow added that this was to be seen as a huge benefit, as a lot of shoddy “market art” would get safely quarantined without anyone having to see it. I sympathize very much with her point of view.

See →.

Bill Carter and Amy Chozick,“Syria’s Assads Turned to West for Glossy P.R.,” New York Times, June 10, 2012 →.

The story has since been withdrawn. More background can be found here: Max Fisher, “The Only Remaining Online Copy of Vogue’s Asma al-Assad Profile,” The Atlantic, Jan. 3, 2012 →.

Michael Stone, “Anonymous supplies WikiLeaks with ‘Syria files,’” The Examiner, July 9, 2012. This article quotes Anonymous’ initial declaration: “While the United Nations sat back and theorized on the situation in Syria, Anonymous took action. Assisting bloggers, protesters and activists in avoiding surveillance, disseminating media, interfering with regime communications and networks, monitoring the Syrian internet for disruptions or attempts at surveillance—and waging a relentless information and psychological campaign against Assad and his murderous and genocidal government” →.

Barak Ravid, “Bashar Assad emails leaked, tips for ABC interview revealed,” Haaretz, Feb. 7, 2012 →.

The emails can be accessed here →.

See the email here →.

See the email here →.

See →.

Studio Herzog de Meuron has been contacted for comment but has not replied as of the time of publication. For the answer from Rem Koolhaas’s studio, OMA, see below.

See →.

Martin Bailey,“Gaddafi’s son reveals true colours,” The Art Newspaper, March 2, 2011 →.

“Rem Koolhaas is very keen to visit Damascus with strong interest to participate in public sector and urban gentrification and regeneration of the city, and trying to keep away from commercial developments and suburban master plans, yet we wanted to sense and feel the current conditions of architectural and urbanization in the city before establishing any commitment . I also wanted to engage Rem in Damascus architectural school and establish internship program with OMA and the university.” See the full email here →.

“Rem Koolhaas is very keen to visit Damascus with strong interest to participate in public sector and urban gentrification and regeneration of the city, and trying to keep away from commercial developments and suburban master plans, yet we wanted to sense and feel the current conditions of architectural and urbanization in the city before establishing any commitment. I also wanted to engage Rem in Damascus architectural school and establish internship program with OMA and the university.” See the full email here →.

Ibid.

Syrian president Bashar al-Assad. See the full email here →.

Suzie Rushton, “The shape of things to come: Rem Koolhaas’s striking designs,” The Independent, June 21, 2010. “An unlikely new client is Libya, specifically ‘a subtle group of people around the [Gaddafi

OMA’s exhibition at the 2010 Venice Biennale, entitled CRONOCAOS, included a section on the Libyan desert. The exhibition was based around “critical preservation stories” →.

A warrant for Saif Gaddafi’s arrest was issued by the ICC on June 27, 2011 →.

Max Fisher, “Syrian hackers claim AP hack that tipped stock market by $136 billion. Is it terrorism?,” Washington Post, April 23, 2013 →.

Hunter Stuart, “Syrian Electronic Army Denies Being Attacked By Anonymous,” Huffington Post Sept. 4, 2013 →.

Joshua Keating, “WikiLeaks to move to Sealand?,” Foreign Policy, Feb. 1, 2012 →

Information under the heading “Swiss Security” on the the ProtonMail website →.

One recent example →.

This ambiguity characterizes popular web tools that are supposed to safeguard anonymity, such as Tor. The Edward Snowden leaks revealed that the mere usage of Tor, or even searching the web for privacy-enhancing tools, actually flags people for NSA scrutiny (see →). A software designed to screen out surveillance actually ends up attracting it.

Angelique Chrisafis, “Leading Swiss art broker arrested over alleged price-fixing scam,” Guardian, Feb. 26, 2015 →. Bouvier has rejected these allegations, putting the blame on the allegedly defrauded Russian oligarch Dmitry Rybolovlev.

Walter Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” thesis XV, in Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt (New York: Schocken Books, 1988), 261–62.

Ali Shamseddine and John Rich, “An Introduction to the New Syrian National Archive,” e-flux journal 60 (Dec. 2014) →.

Note the different strategies for publicizing massive leaks employed by, on the one hand, WikiLeaks, and on the other, Edward Snowden, Laura Poitras, Glenn Greenwald, and their numerous collaborators.

Most pronouncedly expressed by Peter Bürger, Theorie der Avantgarde (Frankfurt: Suhrkamp Verlag, 1974). English translation: Theory of the Avant-Garde, trans. Michael Shaw (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984): 90.

Which might fulfill the traditional role of a “financial tombstone”—a gadget that commemorates concluded transactions →.

However limited basic democracy may have been in Switzerland, given that general female suffrage was not established until 1971, and in Appenzell Innerrhoden not until 1990.

A term invented by Sven Lütticken.

Category

Subject

Credits: Commissioned by Artists Space New York as a lecture. Prior versions were funded by Florence Lo Schemo del Arte Festival and Stedelijk Museum Public Program Amsterdam and preliminary parts additionally presented at the CIMAM 2014 conference in Doha and a talk organised by Victoria Art Foundation Moscow. Crucial research was made possible by the Moving Museum Istanbul and an invitation by HEAD Geneva.

The text tremendously benefitted from editing by Adam Kleinman and Richard Birkett. Thank you Adam Kleinman, Anton Vidokle, Sener Özmen, Fulya Erdemci, Övül Durmosoglu, Aya Moussawi, Simon Sakhai, Savas Boyraz, Salih Salim, Leyla Toprak, Frank Westermeyer, Jenny Gil, Bartomeu Mari, Rivers Plasketes, Richard Birkett, Leonardo Bigazzi, and Hendrik Folkerts.