A Personal Prologue

I grew up in a place where civil war was part of daily life, where safety in public space was divided into day and night, into wide roads and back streets, mountains with cages or fields with burned trees. It was normal to have military tanks patrolling in the heart of town with heavily armed Special Forces. Working as a journalist in a newspaper was dangerous enough to have one assassinated in the middle of the street during daytime. Listening to music in your native language was considered a crime. Imagine a place where primary school kids were investigated for taking part in a painting competition about the International Day of Peace. Growing up in circumstances of radically militarized everyday life with very limited resources, I am not coming from a place where worldviews of “Western moralism”or ethics as “conventional wisdom” were taken for granted. I am coming from a place where I learned the importance of consciousness—more importantly, collective consciousness—when one is isolated both culturally and politically.

Already during the early years of my artistic practice, I had to face a number of polarizing challenges. I remember participating in two significant meetings on April 2 and 9, 2005, in Istanbul with other artists, writers, critics, and students to discuss the notion of a national exhibition, with reference to several exhibitions that had been organized since 2000. Exhibitions about Istanbul, Turkey, and the Balkans, and more specifically the exhibition Urban Realities: Focus Istanbul that was planned to open at Martin-Gropius-Bau (2005) in Berlin, were discussed at these meetings. At the end of them, ten artists—myself, Can Altay, Hüseyin Alptekin, Halil Altındere, Memed Erdener, Gülsün Karamustafa, Neriman Polat, Canan Şenol, Hale Tenger, and Vahit Tuna—decided to withdraw from this exhibition. In addition, an interview by Erden Kosova and Vasıf Kortun, and an article by Fulya Erdemci, were withdrawn from the exhibition catalog by the authors. The show went on, but it became an exhibition about Istanbul without the participation of artists from Istanbul (with a few exceptions). Through this withdrawal we expressed our fatigue over exhibitions based on national identity, over the utilization of artists as illustrations of politics between nations, and the categorization of artists according to geographical, national, or regional specifications. Besides all this, another disappointing thing was the disparity in the distribution of funds among invited artists.

Propositions

As the 19th Biennale of Sydney, 31st São Paulo Biennial, 10th Sharjah Biennial, 13th Istanbul Biennial, Manifesta 10, Gwangju Biennale, and many other cases attest to, we have entered a new phase: the existing institutional protocols and structures of large-scale exhibitions can’t handle the changing nature of spectatorship, sponsorship, usership, and government involvement in art exhibitions.

It is time to talk about what can be done before we hit a dead end, or simply a moment of crisis. What tools can be used? Who pays a greater price? I have a feeling that we lose a lot of time with satirical speculations, misconceptions, and a misguided focus on the wrong questions. We all often face contradictions. As artists, curators, social agents, cultural workers, writers, academics, organizers, students, and museum directors, we constantly need to ask ourselves how much we are willing to compromise while creating the conditions for art’s production.

Our failure is that we often think that simply addressing or criticizing the contradictions is enough. We should start confronting them by inventing ways of reversing the cycle of structural contradictions, as Hito Steyerl explains in her lecture performance “Is the Museum a Battlefield” (2013).1 Steyerl traces the bullets back to their manufacturer. She ends up in a feedback loop. The bullet manufacturer is a major sponsor of a Chicago museum where her artwork has been screened. How do we reverse the loop of circulation? We might say: through sabotage. What kind of sabotage are we talking about? Gayatri Spivak uses the term “affirmative sabotage”—not to destroy but to repurpose and use tools for something else.2 Franco “Bifo” Berardi uses the term “algorithmic sabotage,” referring to counter-strategies of the precariat within the abstract sphere of finance.3

But how can all this be done? Janna Graham has proposed “para-sitic practice” as a counter to target practice.4 Graham says that para-sitic activity is critical of institutional elitism through an antagonistic dialogue between individuals working in cultural institutions and the cultural workers who are invited or commissioned. Graham underlines the importance of the question, “When are we the parasites, and when are we the hosts?” Para-sitic practice aims at broad social transformation by taking advantage of the high profile of cultural institutions, using a “problem-posing” approach instead of a “banking” approach, as Paulo Freire described it: a method of teaching that emphasizes critical thinking for the purpose of liberation, as opposed to the idea of treating students as empty containers into which educators must deposit knowledge.5

At her keynote speech at the International Biennial Association conference in Berlin, Maria Hlavajova underlined the importance of Gerald Raunig’s “instituent practice,” which refers to the reformulated institutional critique introduced by artists such as Hans Haacke and Marcel Broodthaers.6 Then Hlavajova posed this question: “How do we want to be governed and how do we govern?”7 Instituent practice positions itself between governing and being governed through its emancipatory and radical project of “transforming the arts of governing.” Its effect goes beyond the particular limitations of a single field, and it has the potential to force structural change in the areas of patronage, law, the urban, and the control of public space.

Thinking of how to make all these concepts more effective, I would suggest the idea of the “Intervenor”: an autonomous outside voice who nonetheless has the right to act within the institution. Intervenors could not only act within the walls of the white cube, but could also directly intercede when it comes to matters of communication, events, bureaucracy, administration, and even the office space itself.

It is not easy to talk about such an antagonistic position without putting it into practice. Let’s imagine how this would work:

Intervenors could be artists, art workers, cultural workers, or academics who aren’t normally part of the institutional decision-making mechanism, and who are aware of the sensitivities of the local context.

Intervenors would have an officially acknowledged agreement that protects their work from financial and political interference.

Intervenors would have a right to vet all forms of communication before they go public. This would include announcements, press conferences, events, and statements.

Intervenors would act in a time-sensitive manner, and would be flexible in times of crisis; they would not act according to preprogrammed agendas, concepts, exhibition schedules, or locations.

Intervenors could leave when it is no longer possible to challenge the limits of structural change.

Intervenors would be the protagonists who go beyond symbolic and harmless institutionalized critical agency. They would intercede if the institution reacted in an authoritarian or judgmental way to any public concerns.

Magnetic Moments of Collective Consciousness

To get an objective overview, it is essential to continually reframe discussions taking place in the arts community by moving from the abstract back to the concrete. When we look back at history, what comes into focus is the collective consciousness that emerges during what Ute Meta Bauer has called “magnetic moments in time.”8 In order to focus on the consequences of collective acts of refusal, we may now pass over to cases such as Charles Saatchi’s resignation from the Tate’s Patrons of New Art Committee, shortly after the opening of Hans Haacke’s exhibition at the Tate Gallery in 19849; or when the Cincinnati Art Center’s director Dennis Barrie found himself in an obscenity trial because of Robert Mapplethorpe’s “The Perfect Moment” exhibition.10

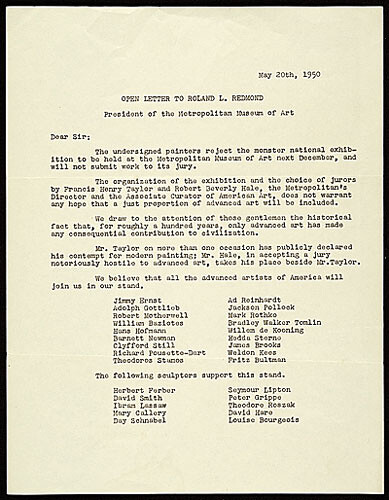

Alongside these individual cases, we can trace the evolution of the collective concerns of international arts communities over the years by looking at a few examples from the last half century. Starting in 1950, the Irascibles, a group of American abstract artists, including most of the leading figures of the New York School such as Louise Bourgeois, Robert Motherwell, Willem de Kooning, and Ad Reinhardt, signed an open letter to Roland J. McKinney, the president of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, demanding an improvement in the presentation of abstract art in the museum.11 The Irascibles’ protest eventually brought change to the museum’s plans for upcoming exhibitions. A few years later, another open letter addressing the architecture of the Guggenheim was published by a group of artists and sent to the museum prior to its construction (1956–58). This time, the case concerned where the art was to be shown. Many artists and critics reacted negatively when Frank Lloyd Wright’s plans became public knowledge. The collectively written letter was addressed to James Johnson Sweeney, director of the museum. It stressed that plans for a spiral walkway and curvilinear slope were “not suitable for the display of painting and sculpture.” The letter was signed by twenty-one artists such as Franz Kline, Robert Motherwell, Philip Guston, and Willem de Kooning.

Alongside the social movements of the 1960s and 1970s, many mega-events of the art community, such as the 35th Venice Biennale in 1968, were struck by protests. The event was characterized by brutal police crackdowns, unfinished pavilions, and artist boycotts. Workers, trade unions, students, intellectuals, and artists united in a coalition on an unprecedented scale. Artists from many different countries took part in the protests by covering up their works or turning them over.12

The history of collective consciousness was elevated to another level when the Art Workers’ Coalition—a coalition of artists, filmmakers, writers, critics, and museum staff that formed in New York in 1969—submitted a letter outlining thirteen demands to Bates Lowry, director of the Museum of Modern Art. The letter demanded museum reform and a better understanding of artistic positions and public concerns in the decision-making process.13

In 1972, ten artists cosigned an open letter to the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung expressing concerns about Szeemann’s curatorial vision for Documenta 5. Daniel Buren and Robert Smithson’s essays and Robert Morris’s letter of withdrawal published in the catalog argued against the artist’s loss of autonomy when the curator becomes author and “exhibition maker,” imprisoned by contextual and cultural determinations. They were also concerned that the gap between artistic and curatorial authorship was not left open to negotiation on ethical or moral grounds.

Among other historical cases, the “No” campaign at the 10th São Paulo Biennale in 1969 (“Non à la Biennale de São Paulo”) was the first large-scale organized campaign. It was initiated by a statement from a group of international artists that included Douglas Huebler, Joseph Kosuth, Robert Barry, and Lawrence Weiner. The statement denounced the brutality of the Brazilian military regime of Emílio Garrastazu Médici (1969–74), and more specifically the violence perpetrated against Brazilian artists and intellectuals. The protest gained a large following and included many Brazilian artists such as Hélio Oiticica, Lygia Clark, Rubens Gerchman, Willys de Castro, Nelson Leirner, Mary Vieira, Antonio Dias, and Carlos Vergara. This campaign reverberated over the next few São Paulo biennials until political changes became apparent in Brazil in the 1980s.

Once again, only a few days prior to the opening, the 2014 São Paulo Biennial faced objections from sixty-one participating artists, who published a collective opposition letter on August 28, this time because of the Israeli funding of the event. The letter appealed to the biennial board to remove the Israeli sponsor logo and return the money. The day after the letter was delivered, Charles Esche, one of curators of the biennial, shared a joint curator’s statement in support of the artists and their position. The Fundaçao Bienal São Paulo eventually agreed to add a note above the logo to “clearly disassociate” Israeli funding from the general sponsorship of the exhibition.14 Even though the foundation didn’t remove the logo from the wall or return the money, this was an example of achieving consensus in a moment when it looked like it wouldn’t have been possible; all the artists remained in the show.

During the same month, on August 18, 2014, the president of the Gwangju Biennale Foundation, Lee Yong-woo, announced his resignation over a controversy surrounding a political painting by Hong Seong-dam that was rejected for the exhibition “Sweet Dew – 1980 and After,” which celebrated the twentieth anniversary of the Gwangju Biennale.15 His resignation followed the resignation of the exhibition’s head curator, Yoon Beom-mo, on August 10. Japanese artists from Okinawa also withdrew their artworks from the exhibition on August 11, stressing that the protection of the freedom of artistic expression aligns with the spirit of the Gwangju Biennale, which was founded in memory of the democratization movement of the 1980s.

I was one of the invited artists who took part in a conditional withdrawal from the 19th Biennale of Sydney in 2014. The biennial experienced weeks of controversy over links between the event and its founding sponsor, Transfield, an Australian multinational corporation that had secured a $1.22 billion contract in January 2014 to work on Manus Island and the Nauru Mandatory Detention Centers. Under Australian law, any asylum-seeker arriving in the country without a visa can be detained indefinitely, which contradicts the UN Refugee Convention of 1951. On February 19, forty-six participating artists issued an open letter calling for the board to “act in the interests of asylum-seekers” and “withdraw from the current sponsorship arrangements with Transfield.” The board’s response was intransigent: “Without Transfield,” it explained, “the Biennale of Sydney would cease to exist.” On February 26, five artists—Libia Castro, Ólafur Ólafsson, Charlie Sofo, Gabrielle de Vietri, and myself—withdrew from the biennial. We were joined by four more artists on March 5: Agnieszka Polska, Sara van der Heide, Nicoline van Harskamp, and Nathan Gray. Exhibition installers Diego Bonetto and Peter Nelson walked off the job over the issue.

In the meantime, other major sponsors of the 19th Biennale of Sydney, such as the city of Sydney, began to question the event’s relationship with Transfield. On March 4, the issue was raised in the Australian parliament, with Green Party senator Lee Rhiannon making a motion in support of the artists. The motion was defeated by the major parties. Perhaps in response to the ongoing controversy, Transfield shares dropped 9 percent over this week, after an initial 21 percent rise when the contracts were first announced. On March 7, just fourteen days before the opening, Luca Belgiorno-Nettis made the decision to step down as chair of the biennial (a position he had held for over fourteen years) and the board announced that it was severing it forty-four-year-old ties with Transfield, the company that founded the biennial in 1973. After our demand was met, seven of the nine artists who had withdrawn from the biennial reentered.16

Since then there has been a chain of consequences: Senator George Brandis has threatened to withdraw government funding from arts organizations that reject corporate sponsorship. After the recent removal of Transfield Holdings’ shares from Transfield Services, now the Belgiorno-Nettis family may return as sponsors, although both companies still share the same name and logo. As Angela Mitropolous has said, “A clear and unequivocal statement from the Biennale would clear up the confusion” about its sponsors. “Any confusion continues to be for the benefit of Transfield Services.”17

Despite the confusions or complexities, the crucial questions are in fact quite simple: How do art institutions face social and ethical responsibilities towards the public, their collaborators, art workers, and artists when it comes to the source of their finances? Where can artistic consciousness meet institutional consciousness?

Misconceptions

Financial decision-making and conceptual decision-making are often separated when it comes to social and ethical responsibilities towards the public. Patronage is often confused with programming the museum. Exhibition and education programs often serve corporate interests.

What are the vital parameters for a biennial to exist? Maintaining credibility and trust is crucial. Usership, spectatorship, and access to Culture (with a capital C) should not be constructed by the cultural elite alone. Therefore, we should ask ourselves several questions before deciding to get involved in biennials: Are biennials still pedagogic sites with transformative aims that can have a lasting effect on civil society? Or are they part of the neoliberal capitalist idea of “festivalism,” which is more concerned with scale, budget, number of visitors, and branding? Do they prioritize public concerns and political autonomy, or are they concerned mainly with profit? Can they act as an intermediary between funding and critical politics, without ethical compromises? Do they truly support social struggles instead of whitewashing them? Do they seek out creative strategies and challenging diplomatic solutions when faced with conflicts and contradictions? Are biennials about providing a space, or becoming a space? How does one maintain self-criticality in the face of institutional elitism? How do we avoid confusing cultural heritage with personal conflicts, and how do we distinguish sponsorship from ownership?

The question of ownership goes along with the question of who has the right to “use the surplus.” Inspired by Henri Lefebvre’s iconic text on “the right to the city,” which demands “a transformed and renewed access to urban life,”18 David Harvey has focused on the “use of the surplus” in current debates around the collective power to reshape urbanization. As Harvey explains, “The right to the city is constituted by establishing greater democratic control over the production and use of surplus.”19 In 2001, Brazil became the first country to introduce a federal policy that wrote the “right to the city” into law, ensuring “democratic city management” and “the prioritization of use value over exchange value.” Biennials, which carry ample meaning for the cities in which they take place, need to be aware of the great importance of negotiating and safeguarding sites of absolute freedom of expression from political manipulation and corporate interference.

Between Joint Action and Campaign

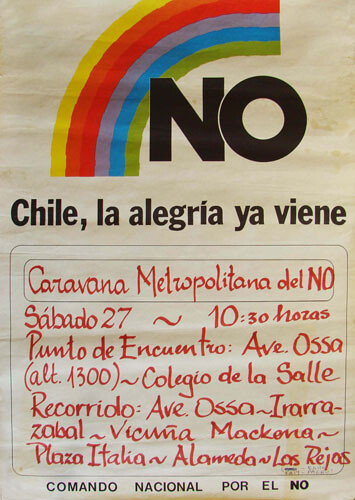

Let’s look at what happened in Chile in 1988. After ruling for sixteen years, Augusto Pinochet was deposed with a 56 percent “No” vote in a plebiscite. After so many years of living without democracy, it wasn’t an easy task to convince Chileans to pick an alternative. Many were afraid to vote against Pinochet, thinking it might cause them to be targeted. In the final weeks leading up to the vote, each side was given fifteen minutes of TV advertising time every night. The pro-Pinochet side used this as propaganda, warning that any alternative would lead to an apocalyptic future. Meanwhile, the “No” campaign, led by a coalition of opposition parties, convened a focus ground spearheaded by Genaro Arriagada. They decided to do the opposite of what the Pinochet campaign had done. Despite other political interests (involving American consultants and the Soros Foundation, among others20), the ad campaign was positive and joyful. It resonated better than a typical far-left campaign that might have focused on Pinochet’s human rights violations. Arriagada and his focus group acted as mediators and worked for years to build bridges between seventeen different groups. Pinochet had the support of the upper class, the business community, the police force, and the army. The “No” campaign had the support of students, workers, human rights activists, victims of Pinochet’s violent regime, many political parties, and the people in the streets.

We can also look at what happened to Ghader Ghalamere. On Thursday, April 10, 2014, Ghalamere, fearing persecution in his home country of Iran, faced deportation from Sweden. While waiting in the departure lounge, he and his family explained the situation to other passengers preparing to board the flight. Once on the plane, all the passengers refused to fasten their seat belts. This collective protest prevented the plane from taking off. Since the flight was unable to take off as scheduled, Ghalamere was removed from the plane and was granted a temporary reprieve.21 The beauty behind this incident tells us a lot about how, when faced with a moment of crisis, a joint action in a constructive and collective manner with clever timing can have a significant effect.

Towards a Collective Epilogue

There is an important difference between the meanings of “boycott” and “withdrawal,” or “campaign” and “propaganda.” When we use these words, we should learn how to avoid getting lost in polemics, cynicism, metadiscourses, complexity, and complicity. Withdrawal is an act of disconnection when there is no space left for dialogue. It might appear publicly as a call to act in solidarity, or as a quiet gesture of nonparticipation with personal consequences. Boycotting can also be used when necessary, keeping in mind that it is only one among the 198 methods in Gene Sharp’s guide to nonviolent action.22 Ekaterina Degot reminds us that subversive positions are fragile and context-dependent, and timing is everything.23 Artists and other cultural workers are fragile when acting alone, facing more personal consequences. After every radical and transformative act, heavy aftershocks might resonate for a long time, which might puzzle us. Finding a strategy is not only about choosing which method is to be used. The lost or not-yet-discovered blueprint is hidden somewhere between a joint action with clever timing and masterminding a long-term campaign. To push and challenge the limits of structural change in a progressive manner today, we need figures like Intervenors who have a right to intercede as turnaround strategists and antagonistic negotiators. Intervenors could mediate in those moments and challenge top-down decision-making, repurposing it in real time.

Hito Steyerl, “Is the Museum a Battlefield,” 2013. Filmed live at the 13th Istanbul Biennial and Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin →.

Gayatri Spivak, An Aesthetic Education in the Era of Globalization (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012).

Interview with Franco “Bifo” Berardi, “Tankefaran,” special English-language issue, Brand 1 (2013) →.

Janna Graham, “Target Practice vs. Para-sites,” presented at Gare du Nord, Basel, November 7, 2012.

Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed (New York: Continuum, 1970).

Gerald Raunig, “Instituent Practices: Fleeing, Instituting, Transforming,” Transversal, Jan. 2006 →.

Maria Hlavajova,“Why Biennial?,” keynote address, First General Assembly of the International Biennial Association at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt, July 10–14, 2014, Berlin.

Interview with Ute Meta Bauer, “Magnetic Moments in Time,” Echo Gone Wrong, Dec. 20, 2013 →.

Hans Haacke, Seth Kim-Cohen, Yve-Alain Bois, Douglas Crimp, Rosalind Krauss, October: The First Decade (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1987).

See Cynthia L. Ernst’s selected links and bibliography of the Robert Mapplethorpe obscenity trial (1990) →.

“The Irascibles,” Life, Jan. 15, 1951. The open letter was published on May 22, 1950 in the New York Times.

Vittoria Martini, “A brief history of I Giardini: Or a brief history of the Venice Biennale seen from the Giardini,” Art and Education.

Lucy R. Lippard, “The Art Workers’ Coalition: Not a History,” Studio International 180 (Nov. 1970): 171–72.

Mostafa Heddaya, “São Paulo Biennial Removes General Israeli Sponsorship,” Hyperallergic, Sept. 1, 2014 →.

“Gwangju Biennale Foundation’s President resigns in controversy over satirical painting of President Park Geun-hye,” biennialfoundation.org, Aug. 19, 2014 →.

Ahmet Öğüt and Zanny Begg, “The Biennale of Sydney: A Question of Ethics and the Arts,” Broadsheet Magazine, 2014.

Steve Dow, “Sydney Biennale 2016: Belgiorno-Nettis family may be back as sponsors,” The Guardian, Dec. 1, 2014 →.

Henri Lefebvre, Le Droit à la ville (Paris: Anthropos, 1968).

David Harvey, Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution (New York: Verso, 2013).

Olga Khazan, “4 Things the Movie ‘NO’ Left Out About Real-Life Chile,” The Atlantic, Mar. 29, 2013 →.

Adam Withnall, “Refugee facing deportation from Sweden saved by fellow passengers refusing to let plane leave,” The Independent, Apr. 14, 2014 →.

Gene Sharp, Politics of Nonviolent Action, Part Two: The Methods of Nonviolent Action (Westford, MA: Porter Sargent Publishers, 1973).

Ekaterina Degot, “A Text That Should Never Have Been Written?,” e-flux journal 56 (June 2014) →.

For their generous input, special thanks go to Zanny Begg, Adam Kleinman, Louise O’Kelly, Mari Spirito, and Serra Tansel.