A few days ago it was my birthday.1 I find that birthdays are the real days of atonement, days when one revisits the past, vacuums it, takes stock, apologizes at least mentally, and distills lessons. Because they are tailor-made and private, I take birthdays much more seriously than somber holidays imposed by religion. Going through this form of accounting I realized, probably once more, that I’m still a militant and a student—a leftist student at that. I realized that I’m still Jewish of sorts, although totally secular. And I reconfirmed that I believe in ethics, although I see that they are increasingly ineffectual and may only serve as a tool for resistance in an increasingly collapsing world.

The student part in this is a consequence of having been raised in Uruguay, in a progressive atmosphere, and with education free for everybody. During my education I absorbed the principles of the Reform of Cordoba, Argentina, of 1918. This reform instituted an anti-elitist and autonomous university system, with students taking part in the government of the institution, with a mission to learn in order to improve society, and with the belief that education is a right and not something to be bought. By the time I studied, all students knew that we were in a privileged period of our lives. We were not mature but we were intellectually okay, ready to expand our knowledge, and aware that during that period we did not yet have to kneel in front of power or be corrupted. We were not consumers of prepackaged goods who approached them with the attitude of buyers. We were the soul and moral compass of the university and therefore also of society. And we knew that this role was something that would stop the day we graduated. Some of us, like me, would look back on this time fondly, others would renege, and many would simply be hypocritical and attribute their former actions to the unrealistic idealism of youth.

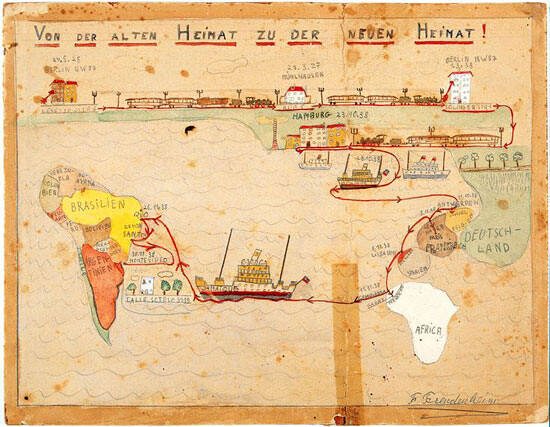

The Jewish part is because I was born into a Jewish family. We had to emigrate from Germany because of anti-Semitism. We were unacceptable to the US because of anti-Semitism. We were lucky to land in Uruguay when I was one year old, and that is what made me who I am. So, I’m a Uruguayan Jew. However, the Jewish part is only an ethical component, a bond with my grandparents who were gassed with the famous six million, all of whom I feel died so that I may live.

The ethics part is probably a product of the other two, and also the more difficult one to keep going. But it’s clear to me that it precedes my need to make art and that it informs the art I make. It’s the root of my belief that when done correctly, art and education become the same thing. It’s because of this that both are ultimately forms of political action. It’s certainly not because of any particular message they may scream to an audience either from the walls of a gallery or from a teacher’s desk.

When I heard that Professor Steven Salaita was fired from the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, my first instinct was to turn down an invitation I had just received to speak there. Being committed to education means that I’m prevented from sponsoring or believing in theocracies, exceptionalisms, fundamentalisms, and hypocrisy. Separate, they are already bad enough. In different degrees of combination they provoke my misanthropy and put me at odds with a lot of countries, institutions, and people, including this university. This means that for me, the problem is not really what direction relations between Palestinians and Israelis take. It’s the fanaticism that may go in either direction and that supersedes the possibility of any sane confrontation between opposing ideas. The confusing of Jewish individuals with Israeli citizens happens on both sides of the spectrum. It tends to ignore that there are some sane people in any population, and it forgets that it is this sanity that should be aimed at in any educational institution. I normally don’t care about biographical information, but here I want to avoid any misunderstandings. Since I believe that technically I could even claim Israeli citizenship, it becomes more pertinent. However, that possibility had never crossed my mind because I don’t conceive of equating religion with statehood. I believe that to equate anti-Zionism with anti-Semitism is intellectual fraud.

So, boycotting the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign was an obvious and easy step for me, but it was also a presumptuous measure. It would only satisfy a conversation with myself and have no effect. After much thought I therefore decided to accept the invitation to go and talk about my work, in spite of misgivings. But I decided that I would not in fact talk about my work. One of the reasons I ultimately accepted the invitation was that the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign is a public university. I believe that what we call education should be both educational and public.

Though not free of charge as it should be, in theory at least the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign is still public, not-for-profit, and hopefully dedicated to inquiry. To boycott this campus would be to mistake the mission of the institution for the mistakes committed by transient and narrow-minded individuals. Fanaticism and stupidity are bad qualities, particularly when those defined by them are rich and in power. Public universities exist to fight these limitations and to make sure that the next batch of rich people who reach power are better. Good education exists to ensure that ethics don’t deteriorate when the state abrogates its financial duties and allows privatization to take over. If the state is badly administered and private funds are required, I understand that there is a need for a financial transaction. It’s the institution’s responsibility, however, to ensure that values are not negotiated away during this process. So I came, figuring that showing support for those that are fighting for these values is more important than saying a self-satisfying “no.”

There are many questions for me personally in the determination of the values we are fighting for, or should be fighting for. In my case, I often ponder what would have happened if my family had not been Jewish. Would I have grown up in Germany? Might I have become a German anti-Semite myself? Or what if the US hadn’t been anti-Semitic? What if it had been open to immigration as promised by the Statue of Liberty, without quotas, walls, or vigilantes? Might I then have become a US chauvinist exceptionalist? The answer lies in the potential strength of my values, helped by ethics and critical thinking. Based on this, I will make my own controversial statement now: The creation of Israel, though understandable in its motivation, was a predictable mistake, and history has proven it so.

My next statement is much less controversial, and stems from my fondness for metaphors. I like metaphors because I see them as an efficient way to compress data. A lot of information is condensed into a verbalized image which, once it is heard or read, unfolds through evocation, creating a rich and understandable totality. It’s a poetic and not a mathematically true compression, nothing to do with JPEG or TIFF images on a computer. So, I will use a walnut as a metaphor for the university. The shell is hard, wrinkled, and will eventually be discarded. But, like the Board of Trustees and whatever parts of the administration collaborate with the Board, the shell puts pressure on the inside, exploits its tenderness, overcomes its possible resistance, and causes it to wither and wrinkle. The dilemma then is: What should define the walnut—the shell or the kernel? As an educator, I obviously choose the kernel. I will try to protect and nourish it, and I will fight the pressure applied by the shell as much as I can.

Due to its own nature, the shell wants to prevail in its mission to train students to be good workers, avoiding any waves of dissent along the way. The success of the university is measured by its public image and not by the individual maturation of its students. As a consequence, the university’s money goes primarily to sports, to industrial research, and to the salaries of administrators, sometimes even after they have resigned. I saw that a former chancellor of the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign who was forced to resign receives $212,000 a year because he helped admit well-connected applicants who normally would not merit consideration. Nice for him. In exchange for this generous severance package, he comes to campus once a week.2

So, focusing on this walnut, we may see the Salaita affair from two angles. One is anecdotal and ripe for a soap opera. The other concerns the philosophical underpinnings and aims of education. Continuing our walnut metaphor, the Salaita affair raises the question of whether education should be a mechanism to satisfy the shell, or a tool to help the kernel exercise its freedom of thought.

In the soap opera version, there is a professor who is led to give up his tenured position in one institution and take a new tenured position in another. He moves with his family, giving up their house and the schools his children attended. He delivers his teaching plan according to the schedule he received, makes controversial remarks on social media networks that he believes are private, and rubs donors the wrong way because they don’t think these networks are private. Finally, the professor is fired two weeks before he is due to begin teaching. We all sympathize with his plight. We are also alarmed because we fear that there might be other similar stories in the future. The story is sad, and the soap opera is badly written by the Board of Trustees, whose members, together with the administration, are the real protagonists. The professor is the unfortunate victim. He plays a secondary role and is doubly victimized: by overzealous administrators, and by bad literature.

The other angle, the philosophical one, is more serious. It actually affects the future of an enormous amount of people, both immediately and later by becoming a noxious precedent. Robert Easter, the president of the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, defended the decision to fire—or to “dehire”—Salaita in an interview with the Chicago Tribune, even before the Board voted on the issue:

At the end of the day, we have to look out for the students and potential students first and foremost … It is important to have an institution where people are not afraid to apply or attend because they feel their views are not respected … Our obligation is to make sure we have the most diverse, inclusive campus that we can have.3

In its doublespeak, the statement seems to belong to the libretto of the soap opera. I understand Easter to be saying that to ensure diversity, there is a need to exclude anybody who does not endorse Israel and/or Zionism. This implies that diversity has to be eliminated in order to keep diversity going—a startling vision for an educational institution. The expectation used to be that a good discussion between opposing views helps education. Educational institutions would actively seek out different opinions in order to have a good level of discussion and avoid excluding the opponent. With Easter’s oxymoronic theory about homogeneous diversity, we end up littering the field with universities that are pro-something on one side, and universities that are anti-something on the other. Or worse, like during the dark McCarthy era, we may end up with only one kind of university.

Another serious implication of the Salaita affair is that the Board usurped academic monitoring duties that belong to the faculty and students. By doing this, the Board confused opinion with policy. I know that the word “opinion” is ambiguous, so I will give it some precision. By “opinion” I refer to a form of gut feeling, an unmediated thought that, because it’s based on beliefs and unconscious sentiments, is not fully examined or proven. In fact, this connection between opinion and gut feeling raises the question of whether the gut accommodates the head, or whether the head conforms to the gut. Either way, the final result is the same.

When the opinions of the Board of Trustees inform policies that should be monitored by those in charge of academic matters, there is reason for alarm. But the gut feelings of the Broad are not the only gut feelings at play in this affair. Salaita’s opinions, although expressed outside the school, were arguably ill-advised. Indeed, we have many derelictions happening simultaneously:

1. Salaita was arguably foolish in the way he phrased and disseminated his opinions. His opinions were just that—gut-feeling statements without any pedagogical value.

2. The university was arguably foolish to hire Salaita without vetting him first.

3. Salaita was arguably naive to accept the appointment without vetting the university first, although prior to this incident, the school’s reputation on free speech issues was apparently not bad.

4. The university arguably lacked a clear idea of the relationship between the space of social media and the space of the classroom. I don’t have a clear idea about this either, but I’m not an institution, so in my case it doesn’t matter.

5. The university and the Board were arguably remiss in failing to establish a policy on the use of social media—or if they did have such a policy, they failed to publicize it sufficiently.

Clearly, the accumulation of all these facts and possibilities cannot take the place of policy. It’s really bizarre that it has managed to do so.

Since Salaita was presumably hired through faculty procedures, he should be fired through faculty procedures. Otherwise, we have opinion overruling procedures that reflect policy. Policy may sometimes fail, but when it does, it should be corrected through legislation, not through the use of power. Trustees are as much responsible for serving as role models as are faculty, and the abuse of power is not a very good pedagogical tool. However, the need to separate opinion from policy is a good topic to be pursued pedagogically. I wonder what would happen if the University organized an in-depth discussion on the question of “opinion vs. policy.” Might it lead to institutional self-analysis and reform? It would be revealing to have a frank discussion that included the chancellor, the Trustees, Salaita, students, and faculty. Besides providing material for many PhD theses, the results could become a point of reference for people both inside and outside the institution. The discussion might even help everybody involved in the affair grow up a little. Otherwise, the next logical and inevitable step is the organization of a local branch of the NSA to monitor tweets and emails. The Board could then make sure that some opinions prevail over others, and that their idiosyncratic version of diversity is instituted.

The conflict between opinion and policy reminds me of when the Uruguayan parliament voted to decriminalize abortion some years ago. When the law reached the president’s desk, he vetoed it because it went against his Catholic beliefs. Though he was basically a progressive guy who was voted into office as the leader of a leftist coalition, the president allowed his personal opinion to overrule a democratically approved policy. He committed an abuse of power. Many years before, in 1990, the conservative King Baudouin of Belgium faced the exact same conundrum. But unlike the president of Uruguay, his actions were admirable. He abdicated for one day. The prime minister took over temporarily and signed the law during the king’s absence. The king’s opinion was preserved and an abuse of power was avoided.

The primary space for opinion is one’s head informed by the gut. The space for the construction of policy is outside the head. Even if the same opinion occurs in many heads informed by many guts and is therefore shared, it still operates in internal space. That is why policies that simply implement opinions—that is, policies that don’t involve an objective analysis of ideas and consequences—are so dangerous. The correct negotiation between the head and the gut is much more complex than a simple enunciation of beliefs, and fights between gut feelings are pointless.

Now it’s time to insert some talk about art, since that is my real field. Opinions are relatively harmless as long as they remain in the private space. But as soon as they leave the private space and are expressed, things change. An expression is an opinion that has just walked out from the head, and that is why Expressionist art risks not being much more than opinion. Once expression starts walking in public space, it becomes communication and therefore stops being harmless. As communication, opinions can have an effect on policy, and policy in turn shapes collective space. While the impact of art on policy is minimal, art nonetheless affects culture. So our responsibility as artists is to act as if art actually determined policy.

This all means that freedom of opinion is one thing, and freedom of expression is something very different. Opinion is allowed to be irresponsible, but when one communicates, one should be accountable for what one is communicating. The way we use the phrase “freedom of expression” does not take these things into consideration. We need to be more nuanced. We should regard “freedom of opinion,” “freedom of expression,” and “freedom of communication” as three distinct categories with different degrees of responsibility. When it comes to censorship, it is “freedom of communication” that is repressed, not “freedom of opinion.” If we decide to insult someone, we should be aware of what might happen afterwards. This does not mean that freedom should be curtailed through censorship. It means that we should know that we have to assume different levels of responsibly in the exercise of each of these freedoms. In a good institution, policy is there to help us be responsible. It is not there to shut us up.

I don’t know if this university is a good institution. But one of the missions of any university is to be a good institution. In light of this, the Salaita incident seems to be a clash of opinions in the absence of policy. There is no consideration of either spaces or responsibilities. If a chancellor resigned in the wake of a scandal and still gets paid more than most faculty; if faculty is hired and then fired not because of fraudulent claims they made, but because of sloppy vetting; if donors can shape the educational mission according to their own opinions and interests; if faculty and students, who are the core and raison d’être of the institution, are ignored in academic decisions—if all this is allowed to occur, then there is no policy in place. Then the university is or may become a bad institution. There is no longer an ethical compass. There is only the fickle, but disguised, rule of opinions.

This leads me, believe it or not, to art education. As it’s usually understood, art transverses distinct spaces. Starting in the private space of opinion and intuition, art breaks out to become expression, and then uses the communicative space in hopes of becoming part of policy. In the case of art, “policy” means the canon, and becoming part of it means garnering museum approval. This process does not include any training or education in responsibility and accountability. Although art tries to mess with brains and hearts, there is no Hippocratic Oath taken in art schools. There are no courses on “ethics and art.” Although everything is about being original and breaking out of the box, there is no discussion about breaking the shell of the walnut.

I have a different view of art. I see it as a very general methodology, as a metadiscipline that includes all other disciplines. In fact, I see science as a minor accident in the acquisition of knowledge. I see science as a field that is seriously limited by having to use logic, causality, and repeatable experiments. There is nothing wrong with any of this, but art is all of this plus the opposite. Art also includes illogic, the suspension of laws, absurdity, non-repeatability, impossibility, and the search for an alternative, not-yet-existing order. This means that art should inform science and everything else as well.

I believe art should do so because it’s the only methodology that allows for unhampered imagination and wonder, for asking in an unrestrained way the question “what if?,” for challenging the given systems of order and speculating about new ones. It’s the ultimate tool for critical thinking.

In other words, art is education. Even if as artists we continue acting as the producers of objects, we should also realize that we are educating others for the purpose of challenging, reorienting, and expanding knowledge. We may keep on polluting the world with things called “art,” and more particularly with “my art,” but we should understand that we are ultimately preparing the space for the development of collective policies that generate the freest and most empowering form of what we call “culture.” We must accept this responsibility and act accordingly.

If we agree with this, the whole idea of art school becomes deeply questionable. This is not a point I want to pursue here because I don’t want to add to unemployment figures. But it’s clear to me that as they function today, art schools aren’t doing much good. The more academic ones start with life drawing and then follow a hypothetical progression based on a linear reading of art history. More modern schools skip life drawing and begin with Painting 1, 2, and 3, mistaking art schools for craft schools. The still more progressive schools are mainly concerned with teaching students how to behave in the art market. None of these schools teaches how to create, because they consider artistic ability to be an inborn quality that cannot be taught.

What remains important in all of this is that art—or better, art-thinking—gives us an individual accountability system that not only helps us to explore the open field of creation: it also helps us to negotiate the transition from the space of opinion to the space of policy. Art-thinking shouldn’t be confined to the making of commodities or the expressing of opinions. Neither one does much for education, justice, or culture unless something else, something more important, takes place.

I decided to read Salaita’s tweets. I started with tweets he sent on September 21, 2014 and worked my way back as far as July 23, 2014. Then I got tired and gave up. I did not find the offensive and incendiary tweets that were quoted in the campaign against him. This only means that those who did find them had a lot more time and patience than I do. Apparently they really needed to find them.

There seems to be a simple and elegant solution to the mess the University has got itself into: let Salaita come to school once a week and pay him $212,000 a year. After all, the University has a precedent for this. Any intellectual damage the Board feared Salaita might inflict would thus be minimized. Even less damage would be inflicted if Salaita’s teaching duties were limited to ethnic cooking or something else that has nothing to do with Israel or Gaza. He should be happy with this arrangement.

Although retired, my vocation is still teaching, so I would now like to propose some assignments:

1. In a tweet he sent on July 30, 2014, Salaita expressed the following: “It seems the only way Obama and Kerry can satisfy Israel’s Cabinet is if they bludgeon Palestinian children with their own hands.” The statement reflects Salaita’s opinion and anger. It is clearly a metaphorical statement, since it is unlikely that the Israeli cabinet sees this as either possible or desirable; nor is it likely that Salaita believes this is possible or desirable. Being metaphorical, the opinion does not express pure, unmediated rage, but instead involves some construction. Please answer the following questions. A) What are the conditions that generated the rage? B) What remains once the rage component is eliminated? In addition, please complete the following tasks. 1) Create a new metaphor so that those conditions may be communicated in a persuasive way. 2) Describe possible policies that might correct the original problem. 3) Replace Salaita’s metaphor with your own, and make your point using a medium you think is effective (social media, a poster, a video, etc.).

2. Similar to a no-fly zone, the University campus has been declared an apolitical zone. No communication involving any political content or intent is allowed to circulate. A) Identify a political cause to be promoted. B) Research the geography and culture of the campus to pinpoint possible paths for the circulation of information. C) Evaluate these circuits for efficiency in communication and possible duration of service. D) Avoid tunnels. E) Choose the appropriate format, and design it the best you can.

3. Let’s assume that there is no free expression allowed on campus except in designated areas such as bathrooms and dorms. But there are not enough bathrooms on campus, and all the dorms are taken. Design new free-expression areas to be placed around campus in easily accessible locations. Free expression has to be contained in these places—it must not spill out. These locations have to be comfortable and weatherproof, and they must stimulate free expression. Use Photoshop or something similar for your presentation.

4. Research existing urban legends. A) Invent a new urban legend. B) Create an advertising campaign on campus with the aim of establishing the legend as fact.

5. Think of an offensive issue that will upset the ethical sensibilities of the University’s student body, faculty, administration, or Board of Trustees—or all of them simultaneously. Develop a campaign to raise funds around the issue, with the aim of increasing the University’s endowment.

This talk was delivered at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign on November 11, 2014.

The former chancellor in question is Richard H. Herman, who served in this position at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign from 2005 to 2009.

Jodi S. Cohen. “U. of I. trustees vote 8-1 to reject Salaita,” Chicago Tribune, Sept. 11, 2014 →