The exhibition starts with the [following] topic: “The serfdom system had been based on the corvée exploitation of the peasant by the noble landowner.” The main content is expressed by means of a mock-up: there is a peasant plowing with an authentic ancient plough; over him, there is a symbol of noneconomic violence—an authentic three-tailed whip, and beside it, a landowner, one belonging to a type of parasitizing lord. In front of the model the material is structured according to [these] topics: 1) first, the consumer character of the landowner household; 2) second, the developing trade which makes the landowner work for the market—that is, the birth of serfdom industry; and 3) third, the bread market, ever-increasing since the early eighteenth century, that leads to the intensification of corvée labor.

The topic “Absolute monarchy consolidates the authority of the lord over the peasant” is presented through the following symbols: a czar’s throne (a copy of the actual throne of the Romanov dynasty), hung high up inside a red velvet niche, [is] supported with the backbone of monarchy on each of its sides—a guard officer and a priest; above it all, [there is] a fierce double-headed eagle holding a whip instead of a scepter and an orb tangled in shackles. The essentially noble core of monarchy is demonstrated by the Charter to the Nobility.

—From “New Exhibition at the Leningrad Museum of Revolution,” Soviet Museum Journal no. 6 (1931)

Today the description of an exhibition above seems rather weird to us, even exotic. It’s hard to imagine that we could see something like this at a contemporary history museum, or even as a curatorial exhibition. However, it’s relatively easy to suppose that such an extravagant installation could come into being as a result of a contemporary artist’s research. What is the reason for this “duality of imagination?” One of the possible answers to this question could be found in the distinction that Boris Groys draws between curatorial and artistic installations in contemporary art. Whereas the former always has to fit into the public field—that is, to adapt itself to society’s ideological model, with all its rules and limitations—the latter still exemplifies sovereign freedom. Such an undercover restriction of liberty usually gets disguised, just like the limitations of Western democracy. The example of the Soviet exhibition in the beginning reflects a unique state of affairs. There are two things that we can discern in this seemingly weird exhibition. First, it is the merging of artist and curator into one person—even if, in reality, this “person” is an anonymous museum team, with its unlimited freedom. And second, it is a claim for the development of an utterly democratic society, which can allow for such a type of expression. This is all rather characteristic of the situation where a social revolution had won and transformed modernist, artistic innovations into an avant-garde, transcending both the role of the institutional and the borders of art. If we think of this model as potentially applied to contemporary artistic production, we can rightly state that it hasn’t lost its topicality at all. It’s certainly logical in some ways: indeed, many of the practices of contemporary art were anticipated by the historical avant-garde and its radical explosion of the 1910s–’30s, albeit in “laboratory mode.” Right now, there is no actual social basis that would allow us to talk about the expansion of democracy’s borders and a new avant-garde project. But the practice of combining artistic and curatorial positions is still highly productive, in terms of problematizing the exhibition as a special form and medium of contemporary art—a medium which is based on hidden and deep rules of social organization. At that, they not only are productive, but also may potentially lead to the radicalization of the primary impulse of the whole modernist project with its present contemporary art condition.

We are in fact already witnessing such a tendency. Thus, it is an increasingly frequent occasion nowadays that art historians have started to describe art history as the history of exhibitions, and not that of individual artistic statements. And often, these artistic statements themselves appropriate the expositional practices of the curators, not to mention the rather widespread practice of an artist acting as a curator of an essentially curatorial exhibition. The latest and most discussed example of such an activity was the Berlin Biennial, curated by Artur Żmijewski.

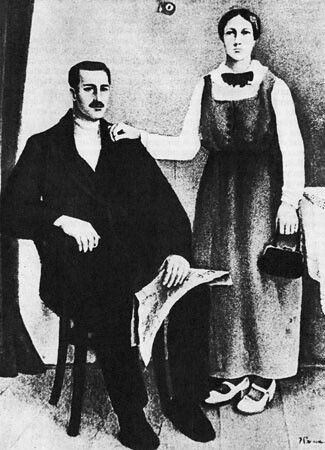

In this respect, the recent shift of artists’ attention from separate works onto exhibition-as-medium can be described as a critique of the bureaucratized version of the contemporary critical art display. This kind of display cannot achieve any tangible results in terms of formulating “correct” dogmatic answers without any real aesthetic changes and with unwarranted hopes of creating social transformation. This gesture is reminiscent of how new waves of the postrevolutionary avant-garde in Soviet Russia criticized geometric abstraction and constructivism for these movements’ bureaucratization and fetishization of the primary critical impulse. The exit out of the vicious circle of negating art’s critical variants was then found in realism and “realistic painting,” utterly free in its treatment of any stylistic methods whatsoever. Thus, post-avant-garde painting practice included the possibility of collage or the rejection of any vivid stylistic marks whatsoever—if this was what the creative idea and reality itself demanded. Russian critic Ekaterina Degot, in pointing at the ideological, idealistic, and oftentimes dialogic basis of this sort of collage technique in Soviet painting of the 1920s–’30s, labels it “conceptual realism”—which, in my view, is rather just. As an example she points to a portrait of Predfabzavkom, chairman of the factory commission, and his wife, painted in 1922 by one of Malevich’s disciples, Georgiy Ryazhsky.

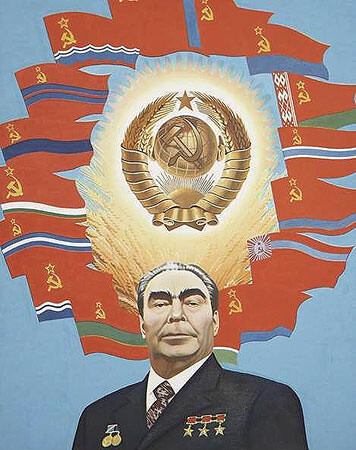

We can see how the artist reflects the notion of painting as an umbrella medium, which implies that features of the picture are based on his conceptual decisions about a critical reflection of reality and can absorb characteristics of all other media. In the case of the above-mentioned portrait of Predfabzavkom, the artist has chosen to represent the chairman in a folk style, a seemingly “unskilled” manner, and to reference typical postures and compositions found in nineteenth-century photography. But it was not only the experiments of the 1920s that followed this logic. The whole development of a Soviet painting style ended up in socialist realism limiting the deconstruction of a visual language, which became its necessary formal minimum for the expression of endless scholastic ideological treatments. It is only logical that such a tendency was used later by the painters affiliated with the Moscow Conceptual School. One of the most remarkable examples of this is the artistic practice of Eric Bulatov, who appropriated clichés of official visual art until his style reached full ambivalence, for example in the portrait of Leonid Brezhnev in the 1977 work Soviet Cosmos.

We can find another radical variant of the same conceptual realist intuitions in the practices of avant-garde Soviet museologists of 1920–30s. At this time avant-garde artists from Kazimir Malevich to Sergey Tretyakov and Aleksandr Rodchenko tried to transcend the borders of art and start producing new forms of living. Each understood the museum only as an educational and professional addition to their art pieces, which were largely traditional in terms of medium.

Then the post-avant-garde artists created the possibility for the critique of the critique derived from rethinking the conceptual role of painting as a medium. At the same time, the museologists of the young Soviet state established a new way of producing museum exhibitions without any media preferences, on the borderline between art and life, artistic and curatorial, critical and weird or postcritical. In its main points such a manifestation repeats the impulses of the historical avant-garde, but with another sense and on another level. Here we can reach an understanding of art and creative effort as part of a political class struggle of suppressed people (with new revolutionary and antireligious museums), movement forward through self-institutional borders (with mobile exhibitions using trains and automobiles for supplying art and knowledge to people, or museums about factories that showed an unknown branch of productivism art), thinking about exhibition as Gesamkunstwerk (as a common feature of museum thinking of this period), critical rethinking and negation of art history (the sociological school of Alexey Fedorov-Davydov), and so forth. And if “weird” examples of exhibitions, as we have seen above in the case of the exhibition in the Museum of Revolution, correspond with post-avant-garde experiments in using collages made of different styles and media as a necessary base for expressing a conceptual view of reality, Fedorov-Davydov’s analytical approach is closer to avant-garde radical negation, but in the post-medium condition, criticizing all types of previous art.

***

The pathway of the development of museum work in Russia’s postrevolutionary period repeats the general cultural quest of the young socialist state. One figure who gained great importance during this turbulent time was the journalist Anatoly Lunacharsky, who as the first Narkompros, or Soviet People’s Commissar of Education,was basically appointed the head of cultural transformations, including those of the museum establishment. In spite of his original renderings of Marxism in the spirit of god-building and sympathies for the avant-garde artists and the Proletkult, it is Lunacharsky who is credited with having preserved and developed the museum network, as well as having brought the hesitant intelligentsia over to the side of the new authorities.1

Another important but now forgotten part of the postrevolutionary cultural landscape was constituted by the army of unprofessional littérateurs from the working class who came together under the common name mentioned above: the Proletkult. Self-taught poets, many of them illiterate, who composed their works literally on the shop floor, had existed also before the revolution, but for good reasons were perceived as a marginal part of the literary spectrum. After the events of 1917, due to the support of the new ideology, the Proletkult became the laboratory where both the strategy and tactics of Soviet cultural production were elaborated.

Immediately after the October Revolution, the provisional government issued a decree on the establishment of artistic and historical commissions, which had the task of revealing, registering, and transferring to museums cultural objects of special value. In 1918, the structure of the governing bodies dealing with museum affairs was bolstered by the establishment of a special unit—The State Museum Fund. It was responsible for the preservation, stock-taking, and distribution of collections and singular objects of museological importance. Besides the governing bodies, the Soviet authorities created the legislative framework facilitating the preservation of cultural heritage. The decree of the Council of People’s Commissars “On the Freedom of Worship, Churchly and Religious Societies” (February 2, 1918) declared all church property to be “national wealth,” and the decree “On the Confiscation of the Property of the Dethroned Russian Emperor and the Members of the Former Russian Imperial House” (July 13, 1918) allowed all belongings of the tsar family to be nationalized. The following decree, “On the Prohibition of Exporting and Selling Abroad the Objects of Special Artistic and Historical Value” (September 19, 1918), played an important role by imposing a ban on exporting the valuables listed in the decree outside state territory without special permission from the Council for Museum Affairs and Preservation of Art Monuments and Antiquities.

At the museum conference of 1917, museums were assigned the task of providing open access not only for scientists and various professionals, but above all, for the masses. Thus, great building projects commenced. In the years immediately following, many palaces, country estates, and monasteries of cultural or historical value were transformed into public museum complexes. By 1920, Soviet Russia had 426 museums, among them twenty-two in Petrograd and thirty-eight in Moscow. At the same time, museums of an entirely new profile emerged: besides the museums of revolution, museums of toys, museums of atheism, and museums of the East appeared, among others.

The very concept of the museum also underwent considerable changes: primarily, it became a crucial part of the state propaganda apparatus. The methods of such propaganda were, however, rather peculiar. The displays at Soviet museums were restructured according to new scientific principles, namely the tenets of dialectical materialism. The “neutral” display of museum material was replaced with an agenda-driven position, which implied not merely an emotional effect on the viewers, but a development of their awareness of the place they occupy within the class struggle. “We do not need the museum to look like a camera of curiosities. We must break the reactionary routine approach to museum-building.”2

At the First All-Russia Museum Convention, there was a harsh critique of the old approaches to display, and a series of innovations were proposed with regard to institutional infrastructure. An ambitious task was brought forth: that of creating a museum of the future, built on a scientific basis by the revolutionary proletariat. The difficulties that come up in working with museum collectives, in most cases consisting of representatives of the petite bourgeoisie, are noted. It is suggested that museums try to attract as many specialists from the proletarian strata as possible to work on the innovation projects. The delegates express the necessity of changing the museum network as such. Thus, Ivan Luppol offered with a new classification of museum institutions based on the Marxist concept of basis and superstructure. Museums got divided into separate groups: the “base” museums of natural science, of technical, economic and sociohistorical profiles, and the “superstructure” museums—the artistic and antireligious ones.

Nevertheless, the most substantial transformations are suggested by the formation of museum displays. According to the speakers, it became necessary to discard a static approach to the presentation of material, based on the display of “art for the sake of art” and “science for the sake of science,” i.e., concentrating on objects in favor of revealing the dialectical connections between historical phenomena and the museum exhibits representing them. From a system of objects, the museum was to turn into a system of ideas that would demonstrate not objects, but processes.

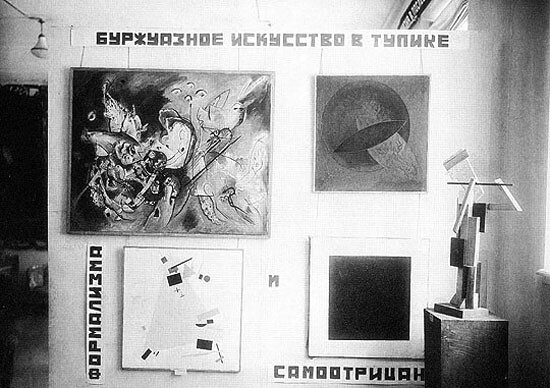

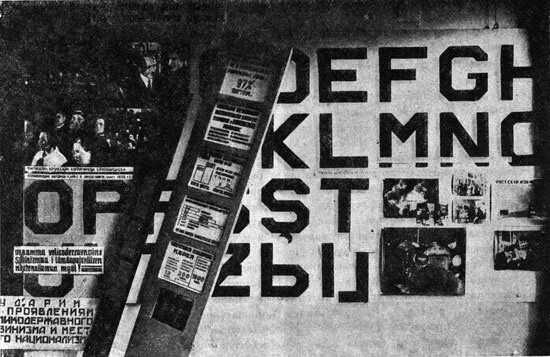

These display principles manifested themselves most vividly in the experiments of the “sociological school” of Alexei Fedorov-Davydov. Working as the director of a department at the State Tretyakov Gallery (the main museum of Russian art in the USSR and later in Russia), he created the then-famous “Experimental Complex Marxist Exposition.” In some sense, this exhibition, where historical works of art were embedded in the “display-complexes” which consisted of the typical pieces of certain classes and historical periods (Fedorov-Davydov did not include typical interiors of the owners of that art, because it could be understood as competing with the Museum of Everyday Life). In keeping with the sociological guidelines of the time, the departments of the Tretyakov Gallery were renamed and restructured. The departments as such were replaced with sections dedicated to feudalism, capitalism, and socialism. The year 1931 saw a large-scale revamping of the displays in the gallery halls.

Fedorov-Davydov pointed out that museums had always shown history and art from the viewpoint of the ruling classes. For the art institutions, it meant that the collections only contained art by representatives of the gentry and bourgeois strata, which led to the radicalization of critical intention. There is a quotation from one of Fedorov-Davydov’s colleagues, N. N. Kovalenskaya, who worked with him on producing the “Marxist Exposition”:

What then is the situation with the immediate emotional impact of the art produced by the classes hostile and alien to us? In order for this art to be understood, it should of course exercise its emotional impact; but can we leave our spectator in the grasp of this immediate contaminating impact? Can we strive for such “contamination” as far as the hedonistic and sensual art of the eighteenth century is concerned? It is clear that we are obliged to expose its serfdom core; should this exposure weaken its immediate impact, it is only to be encouraged.3

Besides art by the renowned masters, each display complex is to be enhanced with artworks not recognized by the bourgeois museum as such. They may include, for instance, various functional graphic productions, such as advertising or folk amateur works (popular prints, stitchworks, works of applied art, painted house utensils, furniture, trade tools). Besides the material not recognized as high art, the sociological display implied the availability of extensive information of a non-artistic kind. The exhibitions now contained materials on the economic situation of certain social groups, maps, diagrams, excerpts from archival documents, publicist’s works, government decrees, memoirs, and literature. The important role of the museum label was now granted a political dimension. As cited above, on the walls presenting the artworks of respective periods were political slogans that acted as binding semantic elements of the display. In this respect, in order to study the transformations of artistic forms in art history more profoundly, the display was supplemented with special halls of art theory that dealt with the basic categories defining the perception of visual art—space, color, and form.

***

The experiments in museum display didn’t last long, and neither did the activities of the Proletkult, production artists, and many other postrevolutionary art collectives. The wave of repressions that swept over creative workers did not spare museum staff either. Many of those who spoke at the First All-Russia Museum Convention were sent to Stalin’s camps. “The Experimental Complex Display”at the Department for New Art of the Tretyakov Gallery was shut down, and its initiator Fedorov-Davydov was expelled from the institution. The vulgar freedom of creative exploration of the ’20s was replaced by the party doctrine of Socialist Realism. Historical, chronological, and thematic approaches were rehabilitated. The value of the object, of the museum exhibit as an undisputed center of museum display, was not doubted anymore. The concept of transcending the limits of art became subject to criticism as outdated leftist extremism impossible to realize under current historical conditions. In the literature on museum studies, it is still pointed out that the provisions of the First Museum Convention had a devastating impact on museum affairs in the USSR. It concerned first and foremost the danger that museums would lose their authenticity, which consisted of the thematic display of museum exhibits, i.e., in the movement towards increasingly artificial displays subjected to a narrative. The indignation of the museologists may well be understood. Indeed, the transformation of the museum into a work of conceptual art would have been an extraordinary event not only for the art of Socialist Realism, but also for the Western artistic quest of those years.

Nowadays, the ideas of vulgar sociologicalism that the Proletkult workers and the representatives of the “sociological” school of museum display were charged with still sound horrible to most intellectuals. The creative expression of the artist, as it was pointed out by Soviet aesthetic theory after the manner of Marx, is able to overcome strict social determinism. As for the relations between the economic basis and the cultural superstructure, there is no linear dependence between them. At the same time, this doesn’t cancel the unquestionable fact that the activities pursued by most cultural producers do not go beyond the limits of the average norm; and, however banal, they will always remain subjected to the dogmas of their class origin. Already during the lifetime of the founders of critical theory, there were plenty of writers who, in spite of their socialist aspirations, couldn’t go much further than praising “the fabric pipe.”4 Still, there were also plenty of those who, in spite of their reactionary views, followed their artistic genius to create sublime and progressive works of art.

The time has probably come to discard the clichés of the past, both left and right, and soberly evaluate the cultural fruits that were borne by the young Soviet state. Let us ask ourselves: Did not the experimentalists belonging to the sociological school of museum display fall into the same trap of fallacy that they accused the art of the past of falling into? If the value of a creative revelation was denied in favor of the sociological context of its origin, why then shouldn’t the artistic museum experiment be buried in oblivion, based on a false interpretation of Marxism-Leninism? But the uniqueness of the artistic solutions suggested by Fedorov-Davydov’s group is indeed astounding. Long before the emergence of total installation practice, long before the formation of defetishized conceptual art, and long before the appearance of a postcolonial theory that legitimized the art of the oppressed peoples of the Third World within the USSR, the people who didn’t even call themselves artists or curators created a work of art, the value of which was merely cancelled because of the mistakes in their interpretation of the Marxist theory of the base and superstructure. The avant-garde character of the art created by Soviet museologists must be reopened to the world, in spite of the critique by the official Soviet bureaucracy and the silence of their Western colleagues, who considered the Soviet experiments of the ’20s as too far beyond the institutional borders of art. Do we deny aesthetic cogency to the sculpture of Pallas Athena merely because it depicts a pagan goddess, and not Jesus Christ or a spaceship? And maybe there is a way to accelerate the whole project of contemporary art that can bring us to a breakthrough into the future avant-garde. If there is, then it lies in a reflection upon the exhibition as a medium, as an example of a statement that criticizes any fetishization of critique which has at its center the experimental combination of the curator’s and artist’s positions based on the breaking of the limits of democratic consensus that manifests itself through the unspoken rules of exhibition-making.

To this end, we can get substantial help by analyzing the formal compositions of both the analytical and the “weird” Soviet museum exhibitions created by the representatives of avant-garde museology.

Lunacharsky was indispensable in the relations with the old university and overall pedagogical circles that convincingly expected full annihilation of science and art by the ‘ignorant usurpers.’ Lunacharsky showed to this closed world that the Bolsheviks not only had respect for culture, but were also not unfamiliar with it. In those days, more than just one lecturing-desk priest had to look at this vandal with stupefaction, as he could read in half a dozen modern languages and in two ancient ones and occasionally showed such versatile erudition that it would easily suffice for a good dozen of professors.” Leon Trotsky, Siluety: politicheskie portrety [Silhouettes: Political Portraits] (Moscow, 1991), 369–370.

Quoted from the greeting letter by A. S. Bubnov in Works of the First All-Russia Museum Convention (Moscow, 1930).

Nikolai Kovalenskaya, “The Experience of the Marxist Exhibition at the State Tretyakov Gallery,” Soviet Museum no. 1 (1931): 50–59 .

This was the nickname invented by Trotsky for naive proletarian art.