A while ago I met an extremely interesting software developer who was working on smartphone camera technology. Photography is traditionally thought to represent what is out there by means of technology, ideally via an indexical link. But is this really true anymore? The developer explained to me that the technology for contemporary phone cameras is quite different from traditional cameras: the lenses are tiny and basically crap, which means that about half of the data being captured by the camera sensor is actually noise. The trick, then, is to write the algorithm to clean the noise, or rather to discern the picture from inside the noise.

But how can the camera know how to do this? Very simple: it scans all other pictures stored on the phone or on your social media networks and sifts through your contacts. It analyzes the pictures you already took, or those that are associated with you, and it tries to match faces and shapes to link them back to you. By comparing what you and your network already photographed, the algorithm guesses what you might have wanted to photograph now. It creates the present picture based on earlier pictures, on your/its memory. This new paradigm is being called computational photography.1

The result might be a picture of something that never even existed, but that the algorithm thinks you might like to see. This type of photography is speculative and relational. It is a gamble with probabilities that bets on inertia. It makes seeing unforeseen things more difficult. It will increase the amount of noise just as it will increase the amount of random interpretation.

And that’s not even to mention external interference into what your phone is recording. All sorts of systems are able to remotely shut your camera on or off: companies, governments, the military. It could be disabled in certain places—one could for instance block its recording function close to protests or conversely broadcast whatever it sees. Similarly, a device might be programmed to autopixelate, erase, or block secret, copyrighted, or sexual content. It might be fitted with a so-called dick algorithm to screen out NSFW (Not Suitable/Safe For Work) content, automodify pubic hair, stretch or omit bodies, exchange or collage context, or insert location-targeted advertising, pop-up windows, or live feeds. It might report you or someone from your network to the police, PR agencies, or spammers. It might flag your debt, play your games, broadcast your heartbeat. Computational photography has expanded to cover all of this.

It links control robotics, object recognition, and machine learning technologies. So if you take a picture on a smartphone, the results are not as premeditated as they are premediated. The picture might show something unexpected, because it might have cross-referenced many different databases: traffic control, medical databases, frenemy photo galleries on Facebook, credit card data, maps, and whatever else it wants.

Relational Photography

Computational photography is therefore inherently political—not in content but in form. It is not only relational but also truly social, with countless systems and people potentially interfering with pictures before they even emerge as visible.2 And of course this network is not neutral. It has rules and norms hardwired into its platforms, and they represent a mix of juridical, moral, aesthetic, technological, commercial, and bluntly hidden parameters and effects. You could end up airbrushed, wanted, redirected, taxed, deleted, remodeled, or replaced in your own picture. The camera turns into a social projector rather than a recorder. It shows a superposition of what it thinks you might want to look like plus what others think you should buy or be. But technology rarely does things on its own. Technology is programmed with conflicting goals and by many entities, and politics is a matter of defining how to separate its noise from its information.3

So what are the policies already in place that define the separation of noise from information, or that even define noise and information as such in the first place? Who or what decides what the camera will “see”? How is it being done? By whom or what? And why is this even important?

The Penis Problem

Let’s have a look at one example: drawing a line between face and butt, or between “acceptable” and “unacceptable” body parts. It is no coincidence that Facebook is called Facebook and not Buttbook, because you can’t have any butts on Facebook. But then how does it weed out the butts? A list leaked by an angry freelancer shows precise instructions given on how to build and maintain Facebook’s face, and it shows us what is well known: that nudity and sexual content are strictly off limits, except art nudity and male nipples, but also how its policies on violence are much more lax, with even decapitations and large amounts of blood acceptable.4

“Crushed heads, limbs etc are OK as long as no insides are showing,” reads one guideline. “Deep flesh wounds are ok to show; excessive blood is ok to show.”5 Those rules are still policed by humans, or more precisely a global subcontracted workforce from Turkey, the Philippines, Morocco, Mexico, and India, working from home, earning around 4 USD per hour.6 These workers are hired to distinguish between acceptable body parts (face) and unacceptable ones (butts). In principle, there is nothing wrong with having rules for publicly available imagery. Some sort of filtering process has to be implemented on online platforms: no one wants to be spammed with revenge porn or atrocities, regardless of there being markets for such imagery. The question concerns where and how to draw the line, as well as who draws it, and on whose behalf. Who decides on signal vs. noise?

Let’s go back to the elimination of sexual content. Is there an algorithm for this, like for face recognition? This question first arose publicly in the so-called Chatroulette conundrum. Chatroulette was a Russian online video service that allowed people to meet on the web. It quickly became famous for its “next” button, for which the term “unlike button” would be much too polite. The site’s audience first exploded to 1.6 million users per month in 2010. But then a so-called “penis problem” emerged, referring to the many people who used the service to meet other people naked.7 The winner of a web contest called in to “solve” the issue ingeniously suggested to run a quick facial recognition or eye tracking scan on the video feeds—if no face was discernible, it would deduce that it must be a dick.8

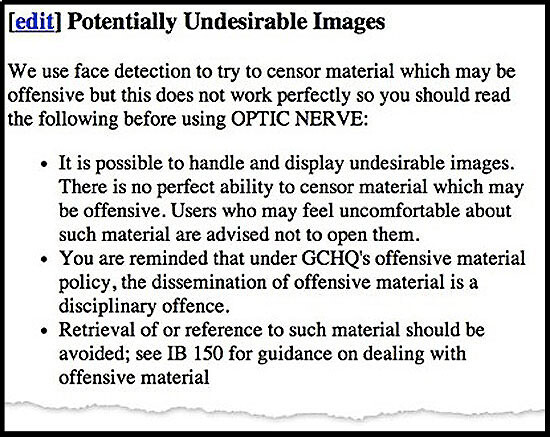

This exact workflow was also used by the British Secret Service when they secretly bulk extracted user webcam stills using their spy program, Optical Nerve. Video feeds of 1.8 million Yahoo users were intercepted in order to develop face and iris recognition technologies. But—maybe unsurprisingly—it turned out that around 7 percent of content did not show faces at all. So—as suggested for Chatroulette—they ran face recognition scans on everything and tried to exclude the dicks for not being faces. It didn’t work so well: in a leaked document the GCHQ admits defeat: “there is no perfect ability to censor material which may be offensive.”9

Subsequent solutions became a bit more sophisticated. Probabilistic porn detection calculates the amount of skin-toned pixels in certain regions of the picture, producing complicated taxonomic formulas.10 But this method got ridiculed pretty quickly because it produced so many false positives, including, as in some examples, wrapped meatballs, tanks, or machine guns. More recent porn-detection applications use self-learning technology based on neural networks, computational verb theory, and cognitive computation. They do not try to statistically guess at the image, but rather try to understand it by identifying objects through their relations.11

According to developer Tao Yang’s description, there is a whole new field of cognitive vision studies based on quantifying cognition as such, on making it measurable and computable.12 Even though there are still considerable technological difficulties, this effort represents a whole new level of formalization; a new order of images, a grammar of images, an algorithmic system of sexuality, surveillance, productivity, reputation, and computation that links with the grammatization of social relations by corporations and governments.

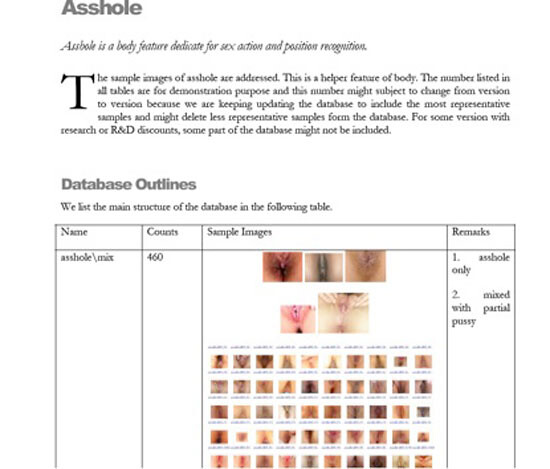

So how does this work? Yang’s porn-detection system must learn how to recognize objectionable parts by seeing a sizable mass of them in order to infer their relations. So basically you start by installing a lot of photos of the body parts you want eliminated on your computer. The database consists of folders full of body parts ready to enter formal relations. Not only pussy, nipple, asshole, and blowjob, but asshole, asshole/only and asshole/mixed_with_pussy. Based on this library, a whole range of detectors get ready to go to work: the breast detector, pussy detector, pubic hair detector, cunnilingus detector, blowjob detector, asshole detector, hand-touch-pussy detector. They identify fascinating sex-positions such as the Yawning and Octopus techniques, The Stopperage, Chambers Fuck, Fraser MacKenzie, Persuading of the Debtor, Playing of Cello, and Watching the Game (I am honestly terrified of even imagining Fraser MacKenzie).13

This grammar as well as the library of partial objects are reminiscent of Roland Barthes’ notion of a “porn grammar,” where he describes the Marquis de Sade’s writings as a system of positions and body parts ready to permutate into every possible combination.14 Yet this marginalized and openly persecuted system could be seen as a reflex of a more general grammar of knowledge deployed during the so-called Enlightenment.

Michel Foucault as well as Theodor W. Adorno and Max Horkheimer compared de Sade’s sexual systems to mainstream systems of classification.15 Both were articulated by counting and sorting, by creating exhaustive, pedantic, and tedious taxonomies. And Mr. Yang’s enthusiasm for formalizing body parts and their relations to one another similarly reflects the huge endeavor of rendering cognition, imaging, and behavior as such increasingly quantifiable and commensurable to a system of exchange value based in data.

Undesirable body parts thus become elements of a new machine-readable, image-based grammar that might usually operate in parallel to reputational and control networks, but that can also be linked to it at any time. Its structure might be a reflex of contemporary modes of harvesting, aggregating, and financializing data-based “knowledge” churned out by a cacophony of partly social algorithms embedded into technology.

Noise and Information

But let’s come back to the question in the beginning: What are the social and political algorithms that clear noise from information? The emphasis, again, is on politics, not algorithm. Jacques Rancière has beautifully shown that this division corresponds to a much older social formula: to distinguish between noise and speech to divide a crowd between citizens and rabble.16 If someone didn’t want to take someone else seriously, or to limit their rights and status, one pretends that their speech is just noise, garbled groaning, or crying, and that they themselves must be devoid of reason—and therefore exempt from being subjects, let alone holders of rights. In other words, this politics rests on an act of conscious decoding—separating “noise” from “information,” “speech” from “groan,” or “face” from “butt,” and from there neatly stacks its results into vertical class hierarchies.17 The algorithms now being fed into smartphone camera technology to define the image prior to its emergence are similar to this.

In light of Rancière’s proposition, we might still be dealing with a more traditional idea of politics as representation.18 If everyone is aurally (or visually) represented, and no one is discounted as noise, then equality might draw nearer. But the networks have changed so drastically that nearly every parameter of representative politics has shifted. By now, more people than ever are able to upload an almost unlimited number of self-representations. And the level of political participation by way of parliamentary democracy seems to have dwindled in the meantime. While pictures float in numbers, elites are shrinking and centralizing power.

And on top of this, your face is getting disconnected—not only from your butt, but also from your voice and body. Your face is now an element—a face/mixed_with_phone, ready to be combined with any other item in the library. Captions are added, or textures, if needs be. Face prints are taken. An image becomes less of a representation than a proxy, a mercenary of appearance, a floating texture-surface-commodity. Persons are montaged, dubbed, assembled, incorporated.

Humans and things intermingle in ever-newer constellations to become bots or cyborgs.19 As humans feed affect, thought, and sociality into algorithms, algorithms feeds back into what used to be called subjectivity. This shift is what has given way to a post-representational politics adrift within information space.20

Proxy Armies

Let’s look at one example of post-representational politics: political bot armies on Twitter. Twitter bots are bits of script that impersonate human activity on social media sites. In large synchronized numbers they have become formidable political armies.21 A Twitter chat bot is an algorithm wearing a person’s face, a formula incorporated as animated spam. It is a scripted operation impersonating a human operation.

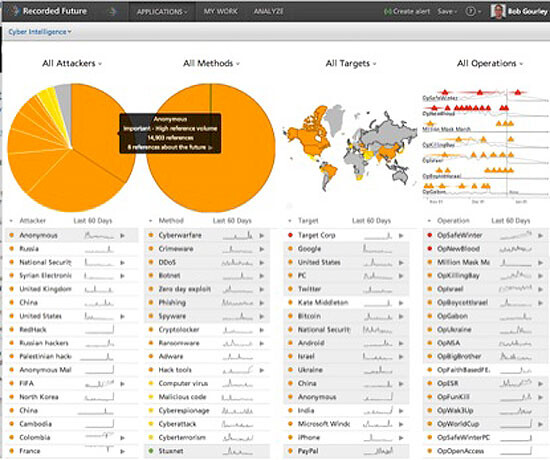

Bot armies distort discussions on Twitter hashtags by spamming them with advertisement, tourist pictures, or whatever. They basically add noise. Bot armies have been active in Mexico, Syria, Russia, and Turkey, where most political parties have been said to operate such bot armies. The ruling AKP alone was suspected of controlling 18,000 fake Twitter accounts using photos of Robbie Williams, Megan Fox, and other celebs: “In order to appear authentic, the accounts don’t just tweet out AKP hashtags; they also quote philosophers such as Thomas Hobbes and movies like PS: I Love You.”22

So who do bot armies represent, if anyone, and how do they do it? Let’s have a look at the AKP bots. Robbie Williams, Meg Fox, and Hakan43020638 are all advertising “Flappy Tayyip,” a cell phone game starring then AK prime minister (now president) Tayyip Recep Erdoğan. The objective is to hijack or spam the hashtag #twitterturkey to protest PM Erdoğan’s banning of Twitter. Simultaneously, Erdoğan’s own Twitter bots set out to detourn the hashtag.

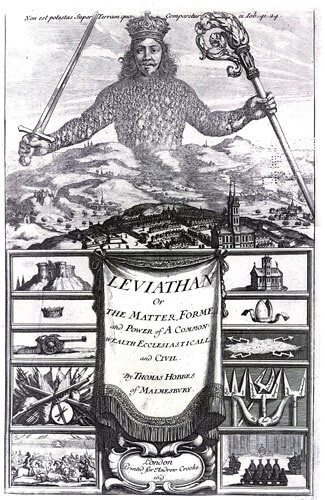

Let’s look at Hakan43020638 more closely: a bot consisting of a copy-pasted face plus product placement. It takes only a matter of minutes to connect his face to a body by way of a Google image search. On his business Twitter account it turns out he sells his underwear: he works online as an affective web service provider.23 Let’s call this version Murat, to throw yet another alias into the fray. But who is the bot wearing Murat’s face and who is a bot army representing? Why would Hakan43020638 be quoting Thomas Hobbes of all philosophers? And which book? Let’s guess he’s quoting from Hobbes’s most important work, Leviathan. Leviathan is the name of a social contract enforced by an absolute sovereign in order to fend off the dangers presented by a “state of nature” in which humans prey upon one another. With Leviathan there are no more militias and there is no more molecular warfare of everyone against everyone.

Here is a face suited for a bot.

But now we seem to be in a situation where state systems grounded in such social contracts seem to fall apart in many places and nothing is left but a set of policed relational metadata, emoji, and hijacked hashtags. A bot army is a contemporary vox populi, the voice of the people according to social networks. It can be a Facebook militia, your low-cost personalized mob, your digital mercenaries, or some sort of proxy porn. Imagine your photo being used for one of these bots. It is the moment when your picture becomes quite autonomous, active, even militant. Bot armies are celebrity militias, wildly jump-cutting between glamour, sectarianism, porn, corruption, and conservative religious ideologies. Post-representative politics are a war of bot armies against one another, of Hakan against Murat, of face against butt.

This may be why the AK pornstar bots desperately quote Hobbes: they are already sick of the war of Robbie Williams (IDF) against Robbie Williams (Electronic Syrian Army) against Robbie Williams (PRI/AAP), they are sick of retweeting spam for autocrats—and are hoping for just any entity organizing day care, gun control, and affordable dentistry, whether it’s called Leviathan or Moby Dick or even Flappy Tayyip. They seem to say: we’d go for just about any social contract you’ve got!24

Now let us go even one step further. Because a model for this might already be on the horizon. And unsurprisingly, it also involves algorithms.

Blockchain

Blockchain governance seems to fulfill hopes for a new social contract.25 “Decentralized Autonomous Organizations” would record and store transactions in blockchains akin to the one used to run and validate bitcoin. But those public digital ledgers could equally encode votes or laws. Take for instance bitcongress, which is in the process of developing a decentralized voting and legislation system.26 While this could be a model to restore accountability and circumvent power monopolies, it above all means that social rules hardwired with technology emerge as Leviathan 2.0:

When disassociated from the programmers who design them, trustless blockchains floating above human affairs contain the specter of rule by algorithms … This is essentially the vision of the internet as techno-leviathan, a deified crypto-sovereign whose rules we can contract to.27

Even though this is a decentralized process which no single entity at the top controls, it doesn’t necessarily mean no one controls it. Just like smartphone photography, it needs to be told how to work: by a multitude of conflicting interests. More importantly, this would replace bots as proxy “people” with bots as governance. But then again, which bots are we talking about? Who programs them? Are they cyborgs? Do they have faces or butts? And who is drawing the line? Are they cheerleaders of social and informational entropy? Killing machines? Or a new crowd, which we are already part of?28

Let’s come back to the beginning: How to separate signal from noise? And how does the old political technology of using this distinction to rule change with algorithmic technology? In all examples, the definition of noise rested increasingly on scripted operations, on automating representation and/or decision-making. On the other hand, this process potentially introduces so much feedback that representation becomes a rather unpredictable operation that looks more like the weather than a Xerox machine. Likeliness becomes subject to likelihood—reality is just another factor in an extended calculation of probability. In this situation, proxies become crucial semi-autonomous actors.

Proxy politics

To better understand proxy politics, we could start by drawing up a checklist:

Does your camera decide what appears in your photographs?

Does it go off when you smile?

And will it fire in a next step if you don’t?

Do underpaid outsourced IT workers in BRIC countries manage your pictures of breastfeeds and decapitations on your social media feeds?

Is Elizabeth Taylor tweeting your work?

Are some of your other fans bots who decided to classify your work as urinary mature porn?

Are some of these bots busily enumerating the names of nation states alongside bodily orifices?

Is your total result something like this?

(*’I`*)

(*’σ з`) ~♪

(*’台`*)

(*≧∀≦*)

(*゚ェ゚*)

(*ノ∀`*)

(/∇\*)。o○♡

(/ε\*) (/ε\*) (/ε\*)

Congratulations! Welcome to the age of proxy politics!

A proxy is “an agent or substitute authorized to act for another person or a document which authorizes the agent so to act.”29 But a proxy could now also be a device with a bad hair day. A less than authorized agent. A scrap of script caught up in a dress code double bind. A “Persuading the debtor” detector throwing a tantrum over genital pixel probability. A drone gone rogue. Or a delegation of chat bots casually pasting pro-Putin hair lotion ads to your Instagram. It could also be something much more serious, wrecking your life in a similar way—sry life!

Proxies are devices or scripts tasked with getting rid of noise as well as the bot armies hell-bent on producing it. They are masks, persons, avatars, routers, nodes, templates, or generic placeholders. They share an element of unpredictability—which is all the more paradoxical considering that they arise as result of maxed out probabilities. But proxies are not only bots and avatars, nor are proxy politics restricted to datascapes. Proxy warfare is quite a standard model of warfare—one of the most important examples being the Spanish Civil War. Proxies add echo, subterfuge, distortion, and confusion to geopolitics. Armies posing as militias (or the other way around) reconfigure or explode territories and redistribute sovereignties.30 Companies pose as guerillas and legionnaires as suburban Tupperware clubs. A proxy army is made of guns for hire, with more or less ideological decoration. The border between private security, PMC’s, freelance insurgents, armed stand-ins, state hackers, and people that just got in the way has become blurry. Remember that corporate armies were crucial in establishing colonial empires (East India Company among others) and that the word company itself is derived from the name for a military unit. Proxy warfare is a prime example of a post-Leviathan reality.

Now that this whole range of activities has long since gone online, it turns out that proxy warfare is partly the continuation of PR by different means.31 Besides marketing tools repurposed for counterinsurgency ops there is a whole range of government hacking (and counterhacking) campaigns that require slightly more advanced skills. But not always. As the leftist Turkish hacker group Redhack reported, the password of the Ankara police servers was 12345.32

To state that online proxy politics are reorganizing geopolitics would be similar to stating that burgers tend to reorganize cows. Indeed, just as meatloaf arranges parts of cows with plastic, organic remnants, and elements formerly known as paper, proxy politics position companies, nation states, hacker detachments, FIFA, and the Duchess of Cambridge as equally relevant entities. Those proxies tear up territories by creating netscapes that are partly unlinked from geography and national jurisdiction.

But proxy politics also works the other way. A simple default example of proxy politics is the use of proxy servers to try to bypass local web censorship or communications restrictions. Whenever people use VPNs and other internet proxies to escape online restrictions or conceal their IP address, proxy politics are given a different twist. In countries like Iran and China, VPNs are very much in use.33 In practice though, in many countries, companies close to censor-happy governments also run the VPNs in a exemplary display of efficient inconsistency. In Turkey, people used even more rudimentary methods—changing their DNS settings to tunnel out of Turkish dataspace, virtually tweeting from Hong Kong and Venezuela during Erdoğan’s short-lived Twitter ban.

In proxy politics the question is literally how to act or represent by using stand-ins (or being used by them)—and also how to use intermediaries to detourn the signals or noise of others. And proxy politics itself can also be turned around and redeployed. Proxy politics stacks surfaces, nodes, terrains, and textures—or disconnects them from one another. It disconnects body parts and switches them on and off to create often astonishing and unforeseen combinations—even faces with butts, so to speak. They can undermine the seemingly mandatory decision between face or butt or even the idea that both have got to belong to the same body. In the space of proxy politics, bodies could be Leviathans, hashtags, juridical persons, nation states, hair transplant devices, moody chat bots, or freelance SWAT teams. Body is added to bodies by proxy and by stand-in. But these combinations also subtract bodies (and their parts) and erase them from the realm of never-ending surface to face enduring invisibility.

Or maybe something much more simple? In an unprecedented self-experiment I pointed my cell phone at Twitter bot @leyzuzeelizan’s (now deleted) profile picture. With as much authority as I could muster, and hoping it would not shoot me back, I ordered it to run a retina scan on her and send it through its network database. My phone identified her in a split second without a fraction of hesitation. @leyzuzeelizan turns out to be no one other than myself, turned from signal to noise, from face to butt and back again several times over, across the crumbling borders of several nation states and countless levels of towering stacks, erasing differences between bodies, nations, animals, and media containers to advertise the work of someone called Hito Steyerl #oral, #xhamster, #videos, #syria How Not To Be Seen.

In the end, however, a face without a butt cannot sit. It has to take a stand. And a butt without a face needs a stand-in for most kinds of communication. Proxy politics happens between taking a stand and using or being used as a stand-in. It is in the territory of displacement, stacking, subterfuge, and montage that both the worst and the best things happen.34

Rubinstein, Daniel and Sluis, Katrina (2013) Notes on the Margins of Metadata; Concerning the Undecidability of the Digital Image. Photographies, 6 (1), 151-158. ISSN 1754-0763 (Print), 1754-0771 (Online). See →. Also see Katrina Sluis’s writings and interviews on this notion.

On the politics embedded into the defintion of noise and information pls see Tiziana Terranova: Network Cultures, p. “Corollary Ib: The cultural politics of information involves a return to the minimum conditions of communication (the relation of signal to noise and the problem of making contact).”

This is actually the question that sparked information theory as such, in a seminal paper by Claude Shannon published in 1948. And of course it also features in trying to design how to network and modulate these parameters across a lot of different platforms. See Shannon, C.E. (1948), A Mathematical Theory of Communication,” Bell System Technical Journal, 27, 379–423, 623–656, July & October, 1948. →.

Adrian Chen, “Inside Facebook’s Outsourced Anti-Porn and Gore Brigade, Where ‘Camel Toes’ are More Offensive Than ‘Crushed Heads.” →.

Ibid.

They work from home in 4-hour shifts and earn $1 per hour plus commissions (which, according to the job listing, should add up to a “target” rate of around $4 per hour).”

Brad Stone, “In Airtime Video Chat Reboot, Nudists Need Not Apply.” June 5, 2012. →.

See →.

See →.

This one, for instance. → a. If the percentage of skin pixels relative to the image size is less than 15 percent, the image is not nude. Otherwise, go to the next step. b. If the number of skin pixels in the largest skin region is less than 35% of the total skin count, the number of skin pixels in the second largest region is less than 30% of the total skin count and the number of skin pixels in the third largest region is less than 30 % of the total skin count, the image is not nude. c. If the number of skin pixels in the largest skin region is less than 45% of the total skin count, the image is not nude. d. If the total skin count is less than 30% of the total number of pixels in the image and the number of skin pixels within the bounding polygon is less than 55 percent of the size of the polygon, the image is not nude. e. If the number of skin regions is more than 60 and the average intensity within the polygon is less than 0.25, the image is not nude. f. Otherwise, the image is nude.

Porn-Detection Software for Videos & Images at Yang’s Scientific Research Institute, LLC., USA (YangSky) →.

See →.

For friends of orderly grammar, the full list: 1. Missionary, Side entry missionary, 2. Squashing of the deckchair, 2. Peace Sign, 2. Butterfly position, 2. Coital alignment technique, 2. The stopperage, 2. The Yawning Position, 2. Octopus Position, 2. Feet-on-his-shoulders, 2. Doggy, Leapfrog, Froggy, Upright doggy, Spread-eagle, Spoons position, Reverse peace sign, Chambers Fuck, Fraser Mackenzie, Inverted Missionary, 2. Cowgirl sex position/Amazon position, Reverse Cowgirl/Reverse Amazon, Reverse Cowgirl Horizontal, Asian Cowgirl →, 2. Horizontal reverse, Armchair, Black bee, Persuading of the debtor, Playing of the cello, Proposal, Split level, Watching the game, Reverse piggy-back, Stand and carry, Standing, Wheelbarrow, etc.

This is Girish Shambu reading Roland Barthes: Sade Fourier Loyola: “Sades system (according to Barthes), like a language, has its own grammar (“a porno-grammar”), consisting of some basic elements. Sexual posture is the main one, and the others are: sex, male or female; social position; location, e.g. convent, dungeon, even bedroom!, etc. Sade then combines these elements together in all manner of exhaustive permutations to elaborate a fully-fleshed out (sorry) set of possibilities. (Girish Shambu).

Dialectics of Enlighenment

Jacques Rancière. “Ten Thesis on Politics.” in: Theory & Event. Vol. 5, No. 3, 2001. (English). “In order to refuse the title of political subjects to a category — workers, women, etc… — it has traditionally been sufficient to assert that they belong to a ‘domestic’ space, to a space separated from public life; one from which only groans or cries expressing suffering, hunger, or anger could emerge, but not actual speeches demonstrating a shared aisthesis. And the politics of these categories (…) has consisted in making what was unseen visible; in getting what was only audible as noise to be heard as speech →.

And all sorts of other hierarchies, obviously.

Ranciere first articulated this idea in “La mesentente” in 1995. Since then the politics of sound and image have shifted quite dramatically with web based and social media.

In Donna Haraways legendary description: A cyborg is a cybernetic organism, a hybrid of machine and organism, a creature of social reality as well as a creature of fiction. Donna Haraway, “A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century,” in Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature (New York; Routledge, 1991), 149-181.

Tiziana Terranova distinguishes between representational and informational space Network Cultures, 36.

The use of bots in influencing public opinion is called “astroturfing”. ““If socialbots could be created in large numbers, they can potentially be used to bias public opinion, for example, by writing large amounts of fake messages and dishonestly improve or damage the public perception about a topic,” the paper notes.” The US DOD has co funded research on the distinction between bot and non-bot on a publicly accessible online platform called BotOrNot.

Elcin Poyrazlar: Turkey’s Leader Bans His Own Twitter Bot Army Posted: 03/26/14 13:25 EDT. The following examples are based on research by Peter Nut and Dieter Leder on Turkish Twitter bot armies, quoted among other places here: Elcin Poyrazlar: Turkey’s Leader Bans His Own Twitter Bot Army Posted: 03/26/14 13:25 See →.

The day is not far when you will be an AK bot too, if you are young and somewhat white, and if you aren’t already.

Unsurprisingly Western secret services seem to have followed suit in programming bot armies to autotune affect on fb. →.

Brett Scott, Visions of a Techno-Leviathan: The Politics of the Bitcoin Blockchain. See , June 1, 2014. →.

See →.

Ibid, 25.

As already predicted by Donna Haraway’s Cyborg Manifesto.

See →.

See David Riff’s fantastic text about Russian bot armies Cheburashka Fascism?

The Etymology of “Agent” and “Proxy” in Computer Networking Discourse, September 18, 1998. Joseph Reagle. Revised: January 15, 1999.

The same seems to have been the case for some of the Assad government servers.

As Tiziana Terranova writes: “A cultural politics of information is crucially concerned with questioning the relationship between the probable, the possible and the real. the cultural politics of information involves a stab at the fabric of possibility, an undoing of the coincidence of the real with the given.” (Network Culture 2004). Also see p 20: “The relation between the real and the probable, however, also evokes the spectre of the improbable, the fluctuation and hence the virtual. As such, a cultural politics of information somehow resists the confinement of social change to a closed set of mutually excluding and predetermined alternatives; and deploys an active engagement with the transformative potential of the virtual (that which is beyond measure).”

Category

This essay originated as a lecture given in May 2014 for Circulationism, a discussion between Josephine Bosma, Metahaven, David Riff, and Hito Steyerl as part of Steyerl’s mid-career retrospective at Van Abbemuseum, curated by Annie Fletcher.