Porter McCray was the director of the MoMA International Program during the 1950s, when several important exhibitions of modern American art traveled through major European cities in the early years of the Cold War. He died on December 1, 2000. In recent years, he has become responsible for the traveling exhibitions of the Museum of American Art in Berlin. This essay is based on a presentation given by Porter McCray for Ashkal Alwan’s Home Workspace Program in Beirut in January, 2014, on the formation of MoMA’s International Program and its pivotal role in constructing an art historical canon of American modern art as an arm of US foreign policy. It appears in this issue of e-flux journal on the occasion of The Unmaking of Art, an iconoclastic exhibition at e-flux viewing art history as a construction, and based on a lecture by Walter Benjamin delivered in Guangzhou, China, in 2011.

—Julieta Aranda, Brian Kuan Wood, Anton Vidokle

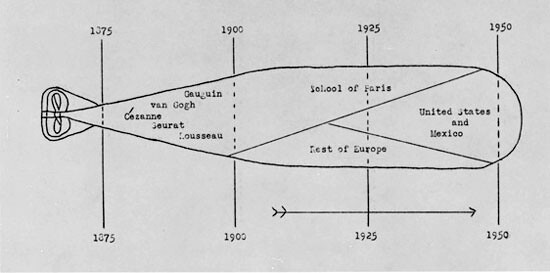

The first press release by the Museum of Modern Art was issued even before there was a Museum of Modern Art, on August 20, 1929. And its purpose was to explain to the public the reasons for having the Museum of Modern Art established in New York. It explains that already in cities like Stockholm, Weimar, Dusseldorf, Rotterdam, and San Francisco there are Museums of Modern Art, and that it is time to have one in New York. And in this press release, we can see how the initiators of the Museum of Modern Art imagined what the Museum of Modern Art would be. It would be what the Musée du Luxembourg was for Paris in the early nineteenth century—the first museum of contemporary art in the country, exhibiting works by living artists. It was the idea that inspired the famous torpedo in time that Alfred Barr made in the first years of the Museum Modern Art.

The Museum of Modern Art started with a loaned exhibition that was very conservative—the Post-Impressionists that were being exhibited at the end of the third decade of the nineteenth century. The entire exhibition was made from various private collections. Just to remind you, for at least six years, the Museum of Modern Art was neither a museum, nor, as Gertrude Stein noticed, could have been modern. Many exhibitions came from various private collections, and there were cases where you might find a painting you like, and you might ask who owns it. And if the owner wants to sell it, you could buy the work from the Museum of Modern Art exhibition. So it was clearly not a museum.

In planning the first exhibition in 1929, there was an immediate discussion about how to start the museum. Situated in the United States, in New York, the question concerned whether we would start with American or European art. Finally the decision was that the museum would open with a loan exhibition of already-established European artists: Cézanne, Gauguin, Seurat, and Van Gogh. And immediately afterward, to acknowledge American art, there was a second exhibition of paintings titled Nineteen Living Americans. Following that, a third exhibition was on the contemporary art scene in Paris, called “Painting in Paris.” A few years later, in 1936, Alfred Barr organized the exhibition Cubism and abstract art, one of the most important exhibition in the twentieth century, which shifted the focus on national schools to international movements. This historicization of the first three decades of modern art was entirely European-based. There were no Americans in this story. Then, after the 1936 exhibition “Fantastic Art, Dada, and Surrealism,” which was also entirely based on European movements, the Museum of Modern Art was criticized for neglecting the current American art scene. And one of the explanations in the 1940 bulletins “American Art and the Museum” was that, “while the Museum of Modern Art has always been deeply concerned with American art, the museum was founded upon the principle that art should have no boundaries, that paintings and motion pictures, furniture and sculpture, from any country in the world, should be shown in the museum, provided they were superior works of art.

This principle is, of course, in diametric opposition to the hysterical nationalism that was then (and is now) sweeping over half of Europe, destroying the freedom of art along with the freedom of speech and religion.”

By that time modern art was already being removed from public view in most European countries and could be only seen across the ocean. Together with various programs, for instance, their circulating exhibition program, this made the Museum of Modern Art from 1930 until 1960 perhaps the most innovative and influential museum in the world. They had various exhibitions that you could rent from the Museum of Modern Art for a price. So not only museums, galleries, but universities, colleges, and schools would call the museum and ask to borrow an exhibition, most of which were European modern art. The exhibitions “Cubism and Abstract Art” and also “Fantastic Art, Dada, and Surrealism” were the first MoMA circulating exhibitions, for instance.

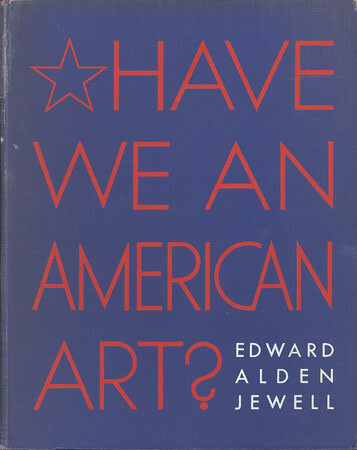

In 1938, the Jeu de Paume held the first exhibition that MoMA decided to bring to Paris, and it was not European but American art. Many French critics were surprised to find a long tradition of American art lasting three hundred years. Most had never heard of American art—when they came to the United States, they would visit museums to find the Italian Renaissance, Dutch Golden Age, Impressionists. Even the focus of the Museum Modern Art in New York was on Europeans. So who were these American artists? The exhibition was titled “Three Centuries of Art in the United States” and included modernists like John Marin, Charles Demuth, Yasuo Kuniyoshi, and John Kane. And then, we see Arshile Gorky, and Alexander Calder. Some of the French press responded to the exhibit at the Jeu de Paume with the question: Is there such a thing as American art? In his book Have We An American Art? Jewell, the art critic of the New York Times, analyzing the press coverage of the exhibition tried to find the answers to the similar questions: “What is American Art?”, ”Who are Americans?”, and “What is America?” He was wondering whether we should “cease to refer to underlying qualities that are racial and national? Should we, instead, henceforth think of them in broad terms of humanity, or of internationalism, of the world’s culture?” Instead of nationalism, Jewell saw internationalism as something that might be American.

Then, after the end of the Second World War, in 1946, in a issue of Art News in October of that year titled “American Art Abroad: Special Issue” we could find the entire section devoted to the exhibition at the Met of the State Department collection of American art titled “Advancing American Art.” It was after all in 1946 that some people in the State Department, including William Benton realized that the cultural image of America in Europe was not so great, that Americans were known for chewing gum, Camel cigarettes, cowboy boots, and so forth, but not for art. So they thought it was time to send an exhibition of American art to Europe and Central and South America. For this the State Department engaged LeRoy Davidson, “visual-arts specialist for the newly formed OIC” to make the collection. And when Davidson sat down to make a collection, he realized it would be more expensive to borrow paintings from various private collectors than to have the State Department buy the similar paintings. So he went shopping with a budget of about $50,000, through New York galleries, acquiring American art, which was the mainstream American Modernism from the previous three decades. And before sending it to Prague, Czechoslovakia, they proudly exhibited what they had collected at the Metropolitan Museum.

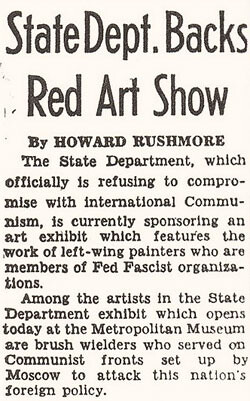

However, immediately after the exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum opened, an article appeared in the New York Journal (Hearst press) on October 4, 1946, with the heading: “State Department backs Red Art Show.” The report detailed how “The State Department, which is officially refusing to compromise with international communism, was sponsoring an art exhibition featuring the work of left-wing Red Fascist painters.” More ridiculously, the article stated that these artists “served on communist fronts set up by Moscow.” Then, Look magazine, one of the major photography and illustration-based magazines, published an article and two-page spread with reproductions of the paintings, under the title “Your Money Bought These Paintings.” The entire collection was perceived to be a misrepresentation of America that created a backlash. Finally after the congressional hearings about the exhibition, the State Department began to realize that they had made a big mistake, simply by deciding to use the taxpayers money to buy art. By the time the traveling exhibition reached Prague, and opened with great success, but the State Department decided close the show early and bring all the paintings back to the United States, hold an exhibition at the Whitney, and sell the entire collection as a government surplus for $5,000.

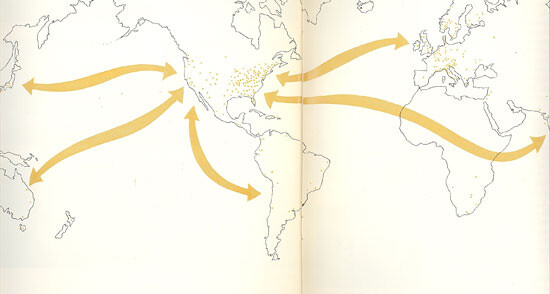

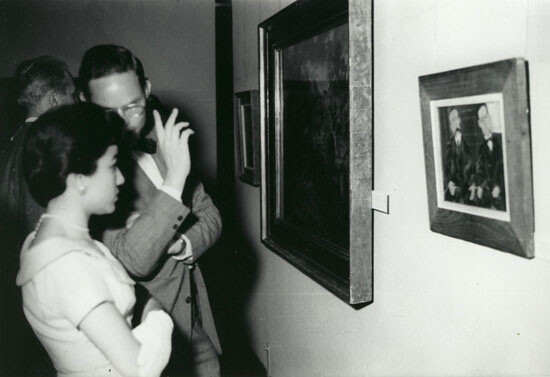

This was the context in which Alfred Barr felt compelled to write a scathing article in a 1952 issue of the New York Times Magazine titled “Is Modern Art Communistic?,” which compared statements about modern art made by Eisenhower, Truman, and Churchill to those made in Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. As a consequence of all this, the Museum of Modern Art as a private corporation decided to establish its International Program, of which I, Porter McCray became director in 1953. With Rockefeller funding, the program’s aim was to organize exhibitions of American art abroad, and to bring art from other countries to the US. During the 1950s, the Museum of Modern Art, through the International Program, organized a series of traveling exhibitions of (modern) American art which passed through many postwar European cities. Those exhibitions, in my opinion, helped establish the first common postwar European cultural identity based on internationalism, modernism, and individualism while establishing a canon and identity for American modern art.

The first of these exhibitions of American art to travel abroad was “Twelve Contemporary American Painters and Sculptors.” Its first stop was in Paris at the Musée National d’Art Moderne in the spring of 1953 before going on to Dusseldorf. The exhibition claimed to represent a wide spectrum of American art, from the abstract painting of Jackson Pollock to works by Edward Hopper. Embassy dispatches from the countries where this exhibition travelled were very positive; this sent a signal to the State Department to revisit its position nearly a decade after its experience with the “Advancing American Art” exhibition. Consequently, the State Department publicly showed its support for the International Program through a 1955 address to the International Council of the Museum Modern Art delivered by George F. Kennan. Kennan, a US diplomat in the Soviet Union, was also responsible for writing the notorious “X” article published in the July 1947 issue of Foreign Affairs, a magazine that originated as an internal telegram outlining the concepts that would become the foundation of US Cold War policy. He later became the American ambassador to Belgrade, Yugoslavia in the ’60s during the Kennedy Administration. The speech was called “International Exchange in the Arts.” Kennan was also a member of the International Council of the Museum Modern Art, which was created in 1953 to strengthen the International Program through an agreement between MoMA and the Rockefeller Brothers Fund. The honorary members of the International Council included the American ambassador to France, C. Douglas Dillon; Senator Fulbright, famous for the Fulbright Program; Dag Hammarskjöld, the Secretary General of the United Nations; and Paul Sachs, Professor of Fine Arts Emeritus at Harvard, who proposed his former student Alfred Barr for the directorship of MoMA. It was an international group. And Kennan’s speech at MoMA served to seal into the mission of the Council the US State Department’s recognition of the political value in supporting these exhibitions during the Cold War. As a result, in 1956, another exhibition was sent to Europe: modern American art from the MoMA collection.

Starting in France with the title “50 Years of Art in the United States—Selections from the Collections of the Museum of Modern Art, New York” contained paintings, sculptures, prints, photography, and architecture. Some 124 paintings and sculptures were selected by MoMA curators Holger Cahil and Dorothy Miller to highlight major directions in American art over a span of approximately fifty years. With works by artists such as Ben Shahn, Morris Graves, Ibram Lassaw (a sculptor born in Alexandria, Egypt), Mark Rothko, and Alexander Calder, it was Pollock who got the most attention. The same exhibition then went to Switzerland, Spain, Germany, England, the Netherlands, and Austria under the name “Modern Art in the USA.” In England, there was an article written that explained to the British audiences that the most important aspect of American art was its cosmopolitan variety. We can read this as one of the possible responses to the Edward Alden Jewell’s question: Who are the Americans? And what is American art?

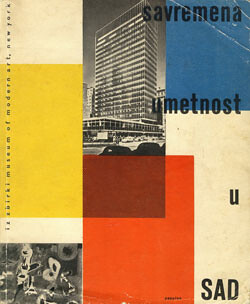

Since Vienna, the last lag of the “Modern Art in the United States” exhibition was close to Belgrade, a representative from the US Embassy in Belgarde approached a person in the Yugoslavian Committee for International Exchange, proposing to invite some people from the committee to the opening in Vienna with the possibility of bringing the exhibition to Belgrade. But documents responding to the invitation show internal discussions in Belgrade starting officially: “Although we are interested in American art, we don’t think we could accept this exhibition on such short notice.” But then there is this comment: “Don’t give compliments on the exhibition, because she said we are interested in American art.” Then, further comments at the end dismiss the entire idea: “In any case, this will be some kind of American Tutti-Frutti.”

But then the US Foreign Service sent an official letter to the president of the Yugoslavian Committee for Cultural Relations in Belgrade, Marko Ristić, describing the entire exhibition to him in detail. And he gave the entire process a 180-degree turn by ending his response letter: “I am absolutely for it!” with instructions to act quickly. And Ristić was no apparatchik, but rather a poet member of the International Surrealist Movement before the Second World War. And immediately the customs office in Belgrade received instruction to be very efficient in receiving the works. Clearly it was understood in Belgrade that the “Modern Art in the United States” exhibition was very important.

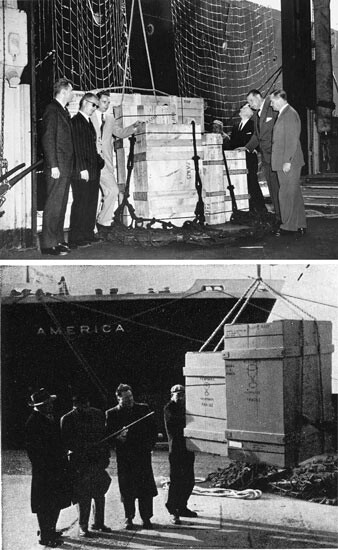

It turned out to be very important for us at MoMA as well. This was the only exhibition for which the museum issued two press releases. The agreement between the US and the Yugoslavian Committee was that the US would pay for transportation from Vienna to Belgrade, insurance, and the catalog, while the Yugoslavian government would cover all local expenses. As Director of the International Program, I sent a dispatch that I would personally come to Belgrade to help prepare the exhibition.

After the opening of the Biennale, I left Venice on June 17, on the Oriental Express. I arrived in Belgrade at 5:55 in the morning of Monday, June 18, 1956, and then checked in to Belgrade’s Majestic Hotel. I learned that David Rockefeller—a board member of the Museum and part of the Rockefeller Brothers’ Foundation, as well as Chase Bank—was coming to Europe, and might be willing to come to Belgrade for the opening. So we believed that, especially given the political situation at the time, the exhibition was an excellent opportunity for the US to demonstrate that Yugoslavs were ready to join the west in becoming actively interested in cultural exchange, through the International Program. I wrote to David Rockefeller that it was extraordinary for the Yugoslav Commission for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries to have accepted the offer of the exhibition within less than seventy-two hours, and that this boded well for the entire venture. It seems they wanted to have the exhibition in Belgrade as badly as we did. So I begged David to come to Belgrade to the opening of what could be the largest art exhibition ever to come to this country. But sadly this is what he responded:

Dear Porter,

Thank you for your letter on June 11 concerning the International Program exhibit in Belgrade. You suggested that I change the plans for our trip to include the few days in Belgrade for the opening of this exhibition. This, I am afraid, I cannot do. Not only are the plans of our family party of seven fully settled and arranged, but I have put myself in display of the Chase Bank in Paris for a number of business appointments after my arrival in June, and that makes it out of question for me to get away to Yugoslavia.

Apparently his business plans with Chase Bank were more important than the exhibition in Yugoslavia. Nevertheless, the exhibition opened and lasted from July 7 to August 6, and included Edward Hopper, Andrew Wyeth, Gorky, de Kooning, Motherwell, Pollock, Tomlin, Klein. The second press release was issued by MoMA announcing the opening of the exhibition, and pointed out that the exhibition was brought to Belgrade “at the invitation of the Yugoslavian Committee.” And before giving my introductory speech, I wanted to know what I should say, since I didn’t know much about the country and the context. So I asked some friends at MoMA, such as Helen Franc, for suggestions. She suggested using d’Harnoncourt’s speech from the opening in Vienna and Kennan’s speech at MoMA, and she quoted some juicy sentences from the Kennan speech. Of course, I had no idea what the political climate in Yugoslavia was. Nevertheless, I made an opening speech. The US Ambassador said a few words. And my host Marko Ristić gave a passionate speech without reading, which I didn’t understand.

As the only exhibition from the Museum of Modern Art to be shown in any socialist country, this was a great success for the Modern. Interestingly, the exhibition included the series of paintings by Ben Shahn entitled Bratolomeo Vanzetti and Nicola Sacco, (1931–32), on a very controversial and tragic event from the late 1920s–early ’30s where these two Italian anarchists were accused of terrorism, tried, and then executed in spite of a huge international outcry. It’s also interesting that this painting was acquired by Mrs. John D. Rockefeller, Jr. from Ben Shahn, and then given to the Museum of Modern Art as a gift from Rockefeller. Many books and catalogues came with the exhibition from MoMA and stayed in Belgrade in the university library. The exhibition was covered by the press, not only in Belgrade but also in other cities throughout the entirety of Yugoslavia. The American Cultural Center in Zagreb had a window display exhibiting photographs of the works shown in Belgrade. Also interesting to note: the Belgrade exhibition closed on August 7, 1956, and Jackson Pollock died in a car accident on August 11. So this Belgrade exhibition was the last exhibition Pollock appeared in as a living artist. The exhibition was completely forgotten afterward for many reasons. One reason might have been ideological, because these were Americans in a Communist country. But also, maybe more importantly, is that from the perspective of Belgrade, Paris was still the center of modernity. America was only a faraway province. Many years later there were lingering memories of Picasso and Henry Moore exhibitions in Belgrade in the ’50s, but not of this exhibition.

Nevertheless, as one of the effects of abstract art being introduced at this MoMA exhibition, an interesting exhibition called “Didactic Exhibition on Abstract Art,” subsequently travelled through several Yougoslavian cities between 1959 and 1962. It was organized by some of the emerging Zagreb abstract artists from the 1950s like Ivan Picelj and Vjenceslav Richter. The exhibition consisted mostly of panels featuring cutouts from photos and books. Interestingly, the exhibition included a Mondrian painting from the collection of the National Museum in Belgrade: an artifact, a sample of abstract art. Since nobody thought much about this painting at the time, it was sent to Zagreb by regular parcel post, without insurance. One of the exhibitions contained a diagram resembling Alfred Barr’s Cubism and Abstract Art diagram, translated into Serbo-Croatian, clearly referencing the influence of the 1956 MoMA exhibition.

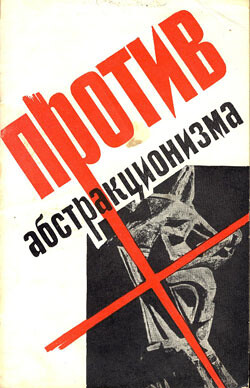

Around the same time, in 1959, as part of a cultural and economic exchange agreement between the Soviet Union and the United States, an official government exhibition called the “American National Exhibition” was mounted at Sokolniki Park, featuring a dome constructed by Buckminster Fuller. Among other exhibits it included the most famous MoMA circulating exhibition, a collection of photographs entitled “The Family of Man” and a selection of American contemporary art which included artists like Grant Wood, Jackson Pollock, Robert Motherwell, Georgia O’Keeffe. The exhibition also included works by Arshile Gorky, who was Armenian; Gaston Lachaise from France; Mark Rothko, who was born in Russia; and de Kooning, who was Dutch. The curator at the Moscow exhibition was Edith Halpert, from New York’s Downtown Gallery. At the time, the Soviet Union still held the position that abstract art was considered unacceptable. The most interest and controversy was generated by the selection of abstract paintings, since in the Soviet Union abstract art was still being dismissed as formalistic and bourgeois. Perhaps it was not an accident that at the time when the paintings of Motherwell, Gorky, and Pollock could be seen by Moscowites, a book titled Against Abstractionism by A. K. Lebedev was published by the Academy of Art of the USSR in Moscow 1959. The book contained chapter titles such as “Abstractionism—Product of Decay of the Bourgeoisie Culture” and “Abstractionism—Enemy of the Truth, Life, Humanity and Beauty.”

Nevertheless, in the end, most of the world accepted the narrative established by MoMA. The International Program went on to spread throughout the entire globe. I like how my former museum would often say: “the Museum of Modern Art has always been international in scope.”