Farocki’s work consists in pointing towards the visible. His art consists in opposing the visible and the obvious. Farocki’s political claim is to demonstrate that in reality nothing is veiled, sealed, or concealed. Meticulous perception is his strategy for emerging from self-imposed nonage. His images do not deal with ideological mist or the ontological mysteries of an image, but with the inertia of our perceiving eyes, with laziness or a lack of mental audacity. His voice-over commentaries prove that the visible differs from the evident. Vision is stratified by implicit historical structures. These organize the gaze and sometimes blind our sight. Based on historical investigation, seeing with one’s own eyes is a matter of political resistance. Observing against the grain of the habitual, against all evidence and blind spots, is the responsibility that remains in a world of machines that have appropriated human sight—or rather, as the installation Eye/Machine and the film War at a Distance (2003) show, machines that have soldered eyes, optical instruments, and industrial weaponry. It is not a matter of pearls, specks, or splinters in our eyes, but of Pershings and Patriots.

Extremely well acquainted with historical and contemporary systems of thought, Farocki has written on historical materialism, semiotics, and structuralism, but has defied all of them in filmic discourse. Cinema’s pledge of truth lies in a certain resilience in resisting elements in pictures or in sounds or voices that escape the intentions and strategies of single authors and single recipients. Cinema’s truth-claim is topological, developing between iconic elements and nodes of montage. It develops between people that discuss films “after the screening … nach dem film,” as a Berlin-based online journal of film criticism is called.1 Cinema’s truth-claim is uncanny, as it turns against the familiar, the accustomed, against what seemed to be clear and certain before the film. Cinematic truth, kino pravda, is manifest in the traces of the past that cinema bears, in spite of individual intentions.

Farocki’s films deal with history as a matter of mémoire involontaire—involuntary and even unwanted memories. His films argue, for instance, that the fascist past is not hidden in postwar German society or cinema, is not veiled by evil powers, as the phrase hätten wir gewusst(had we known) suggests. There is no lack of evidence. On the contrary, Farocki’s films show how the past keeps disturbing and haunting the present in visible, perceivable, describable symptoms. The historian-filmmaker fraternizes with specters, as in his recent film Respite (2007), where Farocki analyzes footage shot in Westerbork, the Dutch transit and labor camp for Jewish refugees—editing, commenting, and amplifying the impact of the images against the intentions of their photographer.

Cinema is the appropriate medium for storing and transmitting history’s truth-claim, since the camera records more than any mind can remember. To appropriate history then is to appropriate the medium by studying its proper logics of recording, storing, transforming, and ordering sensory events. Cinema’s deferments avert the closures of history.

In recent years, one of Farocki’s main concerns was to establish a conceptual history of the moving image, taking as a model the German method of Begriffsgeschichte—a genealogical investigation of semantics and concepts—while at the same time dismantling its idealistic core. Indeed, the project started as a search for something in between, an epistemic object, still nondescript and vague in its dynamics: Wie sollte man das nennen, was ich vermisse (What should one call this thing I am missing?) is the title of the text in which he sketches out his epistemological plan.2

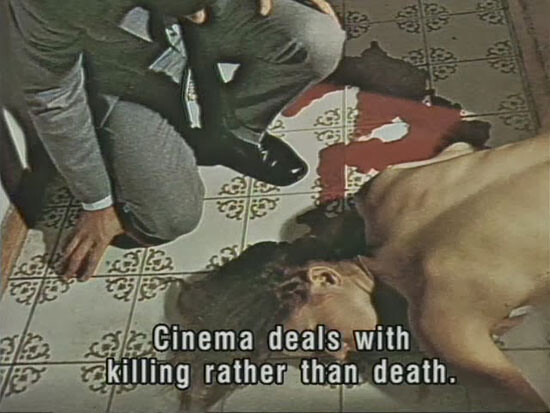

In a series of films and installations, Farocki assembled sequences according to conspicuously recurring cinematic motifs or topics, such as “workers leaving the factory,” “prison images,” “war tropes,” “the aesthetics of consumerism,” and “the semiotics of cinematic hands.” In this conceptual montage of topoi, he would challenge the primacy of the literal in historical thinking. Dismantling the matrix of the medium, these films point towards media formations which implicitly construe meaning and power relations. As in rhetoric, a filmic topos is a commonplace that stays unnoticed in its intangible structure while it structures meaning. Media logics of historiography are at stake in these films, even as subject matter, as in Images of the World and Inscriptions of War (1988). In all of these films, Farocki’s commentaries interfere with the images, exposing unforeseen differences, opposing elements, creating incongruous aspects in the montage. Where his films seem to be repetitive and redundant, they actually establish new distinctions and differences. They are not conceived of as evidence, but as operative images. Cinema creates history instead of representing it. Filmic historiography thus becomes circular, circular-causal, procedural.

Workers Leaving the Factory, edited in 1995, remembers cinema’s first historical topos—“The first camera in the history of film was pointed at a factory,” as Farocki states in his commentary. But his discovery was more precise: the first camera in the history of film was pointed at a factory gate, observing the workers, keeping their movements under surveillance. And, what’s more: there is of course no countershot. Farocki’s montage is a reconstruction of how cinema in its hundred-year history uncannily kept returning to this site, to this shot, as to an historical attitude. Farocki links historical examples of the scene, not chronologically so, but comparing them, thus giving an account of twentieth-century history as seen through the eyes of the camera: Griffith’s Intolerance, Fritz Lang’s Clash by Night, Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Accatone, Antonioni’s Il deserto rosso, documentaries by Wildenhahn and Bitomsky. The space in front of the factory gate proves to have been restaged and reenacted throughout cinema’s history, variegating relations of power and relations of passion inevitably attached to it.

There is one strange and irritating sequence in the film: a truck pulls across an open space, hits a ground-level roadblock, and is blown to pieces. Nobody is on the scene. An electronic camera records the procedure, obviously a testing protocol—a screen test. The truck is visibly compressed, strained, and then explodes. The image, which is repeated in slow motion, transmits a certain pleasure in breaking the seemingly unbreakable façade of a world operating as a stage for production ratios, their effects, and their aesthetics. In front of the factory gate, relations of passion are established in the absence of man—or woman for that matter. In this sequence, Farocki’s voice comes from the Off: “This fantasy of violence, too, remembers the factory’s gate as a historical space, remembers strikes and strikebreakers, occupations of factories, lockouts, fights for wages and justice, and the hopes connected to them.”

The statement seems simple, but contains the whole force and impact of Farocki’s thinking. It is the fantasy itself that he assigns knowledge to. The fantasy of the filmic image itself joins the movements and emotions of people, things, and social movements, desires and fears. The camera dispassionately records. Its eye assembles the history of technologies as well as power and property relations, and relates them to affects, those on the scene and those in the screening space. As cinematic experience, the destruction of a truck is the analysis of condensed labor.

Cinema is a historical entanglement of mind and imaging procedures as movements, compressions, and displacements of thought—Bilder der Welt, multifarious images of the world, instead of Weltbild, one worldview. In the exploding truck scene, Farocki addresses cinema’s trans-subjective memory. It is not a collective memory though, but an invitation to relate to an image. On the one hand, it means scrutinizing one’s own strange and strangely familiar feelings at the sight of the truck’s fragmentation. On the other, it is to recognize the scene as one in a series of shots observing factory gates, an example in a series of security logics and logistics, beginning with the Lumière Brothers observing “their” workers in Lyon in 1895, collecting reenactments of the site in different shades of violence up to contemporary electronic surveillance dispositives that control the labor forces of contemporary societies.

The violence expected in the scene of the tested and destroyed truck updates and refreshes constellations of resistance, strikes, and battles where nothing of the kind is actually visible. It is the force of destruction that points to violence contained in the production process, the one of the truck and the one that the security device is built to protect. It is the energy released in the picture that recalls labor disputes. In the missing countershot, in invisible editing, in gaps between shots, and in the elliptical phrases commenting on the images, sense and meaning are exposed. Historical contingency surfaces: Could the workers not have left the factory? Could they have crashed the gate? Could they have appropriated technologies and machines? Could they have decided on forms of producing and distributing what they worked for amongst themselves, and could they then have exited the factory, emerging from self-imposed nonage, leaving in peace? History as the camera, or rather as cinema, records it, gives a relentless account of facts, moving objects, and persons, of situations, distances, light, and dark, thus recording reactions, behavior, attitudes of people in a situation. As a whole, cinema thus also records the visions people have, the actual and the virtual at the same time.

In Workers Leaving the Factory, Farocki addresses the topos as a rhetorical techne, a cultural technique to organize and preserve power relations as elements of images and imaginations. The confrontational choque between cinema’s audience and cinematic image renders this relationship perceivable, makes it visible, yet hardly consciously so. In pointing towards the image of destruction and the choque or pleasure it evokes, Farocki points to the visibility and perceptibility of history beyond the obvious. In returning to the site of the factory gate, the scene addresses the frontier of interests at the interface between the production site and private lives, controlled labor time and uncontrolled leisure time, capitalist production modes and personal curiosities that drive all sorts of investigations, constructions, orders. At the factory gate, antagonist social forces clash. The series of different sequences focus our attention on a time-space constellation in which individual and collective systems collide, in different contexts but always in the same supercharged constellation. Therefore, the site of the factory gate is present in cinema as a topology of social relations as well as an emotional frame of reference. Farocki’s analysis is not concerned with the essence of things or ontology, but with relations.

In his fragmentary Notes sur le cinématographe, Robert Bresson writes: “Film de cinématographe où les images, comme les mots du dictionnaire, n’ont de pouvoir et de valeur que par leurs position et relation.”3 What seems an eminently structuralist statement concerns the non-ontological concept of cinematic language in general. Cinematic images and cinematic historiography derive their impact from being a part of a larger cinematic memory, whose structure, positions, and values have charged our relationships and have directed our behavior, in private as in labor disputes.

According to Farocki’s cinematic critique, filmic images deprive us of a stable center, a dependable matrix of fixed frames. In this, Farocki’s work with images resonates with a deconstructive approach, mostly avant la lettre. This is not altogether surprising. Hanns Zischler, one of Farocki’s early collaborators, translated Derrida’s De la grammatologie. Philosophical discourse among the Filmkritik crowd was elaborate, theory highly valued. Cinema, however, added something to procedures of criticism and deconstruction that challenged political thought, especially for the generations that were experienced in new media. To think in films is to deal with a lack of security, of centers, of stable systems of thought. Filmic images call for supplements provided by imaginative minds, by a certain rage against injustice. They call for a conception of history as stories of transient and vulnerable beings, of unsheltered lives, minding the non-famous people and regarding oneself as mortal.

History is, as one of Farocki’s earliest films, Inextinguishable Fire (1969), proves, a matter of living bodies linked to machineries of the visible—which are, as we now know, extensions of industrial weaponry. This early film defies television reports on the effects of napalm in the Vietnam War. But as Farocki shows by extinguishing a cigarette butt on his arm to allegedly evoke empathy, there is no such thing as empathy with inconceivable pain. Farocki, in the position of the omniscient news reporter, argues: “When we show you pictures of napalm victims, you’ll shut your eyes. You’ll close your eyes to the pictures. Then you’ll close them to the memory. And then you’ll close your eyes to the facts.” Depicting and showing the effects of violence will always come too late to prevent suffering and injustice. Farocki’s concern is to compose images that will interfere with events, modify them. To do so, this early film returns or proceeds to the factory gates: “When napalm is burning, it is too late to extinguish it. You have to fight napalm where it is produced: in the factories.” Recalling the series of workers leaving factories, we remember that the Lumière plant in Lyon produced photographic plates. It was, in a way, a chemical plant. Maybe the workers left happily because they knew that they were producing the light side of weaponry. Maybe they left happily because they didn’t know about the social control that photography supplied to aid in preventing the sabotage of factory production. Maybe they left because in capitalism, the entertainment industry can never be separated from weapons production, as Farocki taught. Farocki’s historiography lesson is topologically complex and politically simple: every shot contains a slight messianic trace of its own countershot. It is not evident. Find it!

See →

In Suchbilder: Visuelle Kultur zwischen Algorithmen und Archiven, eds. Wolfgang Ernst, Stefan Heidenreich, and Ute Holl(Berlin: Kadmos Verlag, 2003), 17–30.

Robert Bresson, Notes sur le cinématographe (Paris: Gallimard, 1975), 17.