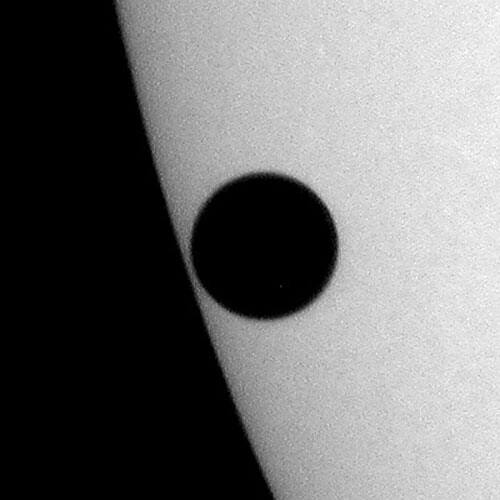

“Black Drop Effect”

It would likely be the last time that the medium of motion picture film would be used to record the transit of Venus across the sun—and Venus would once again elude technology’s grasp. As artist Simon Starling narrates from his position amongst astronomers prepared worldwide to document the event, Venus approaches the limb of the sun—then appears to drop a bit, frustrating attempts to measure the star by the planet’s progress.1 No imaging technology had ever duplicated its own results or any other’s in showing what had just happened. And this year’s cosmic misbehavior was occurring in 2012, with all the energies of the Mauna Kea Observatories trained upon it—not in 1613, when a young Jesuit transcribed the sun spot onto a paper screen for the first time; nor in 1769, when Captain James Cook was dispatched to Tahiti to supposedly make his own observations of the transit of Venus, with similar results when compared with the figures of others: as Starling notes, this was an experiment that was to “prove the inadequacy of astrological measurement … for refining the mean earth-sun distance … [despite] vast international collaborations.” But Cook would discover that the expedition was a cover: secret instructions from the Crown instructed him to journey on from his observation post to continue the search for Terra Australis Incognita. When he did finally land at Botany Bay in 1770, claiming the territory for England, the transit of Venus would have been fresh in the minds of the aboriginal peoples he encountered there, who for reasons not understood then or now were little surprised by the sudden appearance of the Endeavor …2 Analysts intrigued by what Starling’s film is doing turn to other sites, including parallels with French astronomer “Pierre-Jules-Cesar Janssen who brings together the study of astronomy and the medium of film, just as Starling has done.”3 Or to the artist’s own voiceover: “In the universe, there are no ephemeropteraic moments—events go on forever, travel everywhere, are everywhere and everything.”4

But of course, the field is infinitely open. For example, Black Drop’s long sequence showing Starling painstakingly cutting and splicing film strip suggests its own ruse of recovering materials of colonial archiving not only “for the last time,” as he tells it, making a contribution to the “black drop effect” of celestial cinema, but perhaps to witness with his own eyes the blot on the British Empire’s “sun which never sets.” In one shot, Starling’s own eyes screen the event in reverse as he is shown gazing at the images he is editing: his dark irises are two black “suns,” the sun reflected in his eyes two tiny spots of light. “Being there” as part of a technoscientific media event implicates the artist in a cosmopolitical distortion of Aboriginal “worlds of vision” (as Eduardo Viveiros de Castro terms the cosmologies of Amazonia.)5 And as some Aboriginal peoples regard the planet, Starling as implicitly Cook was enjoined to mark with them by other means and names the tenuousness of any natural future for knowledge: from northeastern Arnhem Land, a Dreamtime narrative tells how the star Barnumbir lives on the Island of the Dead, and is so afraid of drowning as she travels across the sea from morning til night that two old women must hold her on a long string, pulling her back to shore at dawn and keeping her tucked into a basket during the day.6

This is Povinelli’s message for approaching “geontologies.” As she tells it when describing her collaborative project to produce digital archives with the Karrabing of Australia for a “living library,” the work is to hold for the future images of local lives in tension between colonial-induced poverty, and the invisible heritage of Dreamtime productivities—as it were, placing these on a long cyberstring controlled locally, for managing states of fear.7 The fears she articulates are many: of drowning in the forces of violence that are overtaking local communities; of drowning in feeling helpless to protect their natural cultural orders; of drowning in climate change creeks and beaches like that of Chepal—not just a resemblance to an ancestral woman, but an event site of a rape that must not be forgotten; Chepal who still lies there, “bioforming the subjectivity of the Karrabing,” and further, “mark[ing] a legal border, [as] a legal relation”—in these two capacities supplying a “pathway for public affect”—generating what I think of as a warm commons that does not deny access to market capital.8 Both rape and healing take many forms, after all, literally and figuratively.

This complex geontological diplomacy, which conveys terms of reference for worlding otherwise than by dominant ways of knowing, enjoins us to hear not only what natural entities might have to tell humans in their own terms, and vice versa, but to study how nature-culture differences might be scaled to the purpose.9 Further, the apparatuses of diplomacy at any site call for consideration of how knowledge exchange might be warmed to the project—might employ affective onto-dispositifs: devices which incline worlding ways to warm protentively to others’.10

***

Recently, I was captivated by a paper by Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, “The Forest of Mirrors,” in which he quotes at length a “dream of origins” from the Yanomami thinker and political leader Davi Kopenawa. Kopenawa tells how “the xapiripe spirits have danced for shamans since the first primordial times and … continue to dance today. They look like human beings but are as tiny as specks of sparkling dust … their paths look like spider webs shining like moonlight.” Only shamans, enabled by the powder of the yakoanahi tree, can see their images, which are described as “magnificent,” “thrilling” to behold. But while the text itself is clearly “a quite extraordinary document,” as Viveiros de Castro appreciates, the ethnographic collaboration that brings it to light is compelling in its own right:

Above all [the mythic narrative] impresses with its richness and eloquence, qualities that derive from the decision of the two co-authors to implement a discursive strategy with a high informational content and great poetic-conceptual density. In this sense, we are presented with an “inventing” of culture (sensu Wagner) which is also a masterpiece of “interethnic” politics. If shamanism is essentially a cosmic diplomacy devoted to the translation between ontologically disparate points of view, then Kopenawa’s discourse is not just a narrative on particular shamanic contents—namely, the spirits which the shamans make speak and act; it is a shamanic form in itself, an example of shamanism in action, in which a shaman speaks about spirits to Whites and equally about Whites on the basis of spirits, and both these things through a White intermediary.11

Here, I stress the critical point of cosmic diplomacy, on one level, for adding into the mix of voices and doings of spirits and humans, some of nature’s own; on another, for asking what the poetics of “shamanism in action” might be offering science in action, in the service of a cosmopolitical consciousness (as Stengers conceives of this), and vice versa. This “dance” of translatability opens to recognizing for the myth it is any possible “escape from perspective” which, as Goetz Hoeppe takes up the point from his theoretical ethnography of astronomical practice, has historically “been conceived as a pathway to objectivity” by scientists.12]: 597–618) and Thomas Nagel (The View from Nowhere, 1989), although what comes to mind here are references to Galison’s important argument in his Image and Logic concerning the translation of different professional languages into workable terms in the context of collaborative scientific projects.] Further, it appreciates that “observing and theorizing are perspectival not just in a geometrical-optical sense, but more generally so in terms of the diverse properties of the instruments, models, and theories which scientists use and the aims they use them for” [emphasis mine]—a point of Giere’swhich Hoeppe echoes in his study of astronomers, who work in effect collaboratively from widely separated field sites.13 The point bears extending to the aims of shamans, ethnographers, and the objects of their study. By placing reflexivity at the armature of accountability for what Hoeppe terms the “tacit cosmologies” of experienced scientists who routinely subject their data sets to diverse “evidential contexts” and to their own professional histories as a kind of “sanity check,” we find ourselves positioned to examine moments when specialist knowledge and aims in different locations warm to each other by the invitation of not-quite or not-yet perceivable, but (as themselves only) inherently trustworthy, natural phenomena—a practical expression of what Eduardo Viveiros de Castro terms “multinatural formations.”

Consider further these scenarios of diplomatic first contact.

Of Moons and Misbehavior

I imagine myself in the New World with Columbus for the first time … a symphony of sounds, of colors, of smells, of desires, and of hopes. Then I imagine myself on the moon with the astronauts, and all I see is gray, dust and barren rocks, and the earth I long for is far out of reach.

—Claude Lévi-Strauss14

In a recent paper, philosopher and historian of science Simon Schaffer turns his mind to the case of the Ensisheim meteorite that collided with earth in 1492, in the region of Alsace. Schaffer writes how people have tried to make sense of the rock since its arrival amongst us. But more than as an object of historical interest, he wants us to consider the meteorite’s capacity to “speak” as a thing, arguing that it can tell us more eloquently about itself than “those who would fetishize [it] under the regimes of [the] iconoclasm and demystification” to which it has been submitted. He offers this brilliant explication:

There’s a specific topography associated with these regimes … it’s as though objects become things when they object … “We begin to confront the thingness of objects when they stop working for us,” writes Bill Brown, adding that such fetishism should be seen as a condition for thinking about how “inanimate objects constitute human subjects.” Such remarks call for a specification of the places where objects can be deliberately made to stop working for us and misbehave so much they become things to confront and understand. In the life of things such as the Ensisheim stone, these include the field site and the lab, the cabinet and the museum, where objects’ recalcitrance is somehow ingeniously turned into a pathway for understanding. There the embeddedness of things is challenged by change and alien confrontation.15

In stating his argument for listening to things on their “thingness,” Shaffer notes Heidegger’s distinction between things and objects: the first, self-organized, eloquent, and “craftily autonomous”; the second, defined as the sum of their empirically observed properties. How easily missed, the way that things get things done their way, in relation to the socios of entification in which they are situationally embedded. Add to this thought the resultant risks of hasty transfers and translations across the “pluriverse” of human and nonhuman actants within an accelerated informatics of biocapitalism, and we begin to see the value of warming up the epi-ontologies we live by—of acknowledging how and when affect gets into the act of constituting “the shifting nature of epistemic relations,” as Marilyn Strathern puts it in a dialogue with Donna Haraway,16 in our worlds of relations. What Lévi-Strauss imagines he would long for from the moon is the capacity to be moved there beyond the engineering ontology that in large part would have gotten him there, to a poetic sensibility—to encounters with the sensuous wetworlds of an animated, perchance misbehaving earth and its earthlings.

I cannot think of a more apt site for following out this line of inquiry than the first contact of Schaffer’s meteorite, a disinterested cosmic entity, with humans who are unlikely even to realize the extent of their implication in its state of being, or for that matter in the cosmic force fields and human technologies which brought them into contact with the thing to begin with. With this in mind, I take up Schaffer’s point about misbehaving rocks and alien confrontations, though by a different route, and to ends that ethnographers of indigenous worlding would not find in the least exotic. If things like extraterrestrial rocks speak of “the vast range of locations in which things live”17 they speak also of the vast range of felt connections they elicit. The issue is not, I hasten to clarify, one of “cosmologizing the human,” as Robbert puts it in his terrific piece “The Mischief and the Manyness,” referring to William James’s, and later Latour’s, concept of the “pluriverse.”18 Rather, I seek to approach first contact between disinterested and interested entities as a matter of degrees of affective mobility: What motivates first contact to move beyond connection, into a future of sustained engagement—and perhaps even of cosmopolitical sublimation?

Listening to Sabarl Moon

During my fieldwork with the Sabarl islanders of Melanesia in the mid-1970s, I was approached by Soter, a local political leader, who wanted to talk about the moon rock he had recently observed on a plaque in Port Moresby. The rock was one of many samples on tour from the Apollo program, and was accompanied by pictures of the lunar landing. Soter was deeply intrigued by what he had seen. Upon returning to Sabarl, he would report that the moon was “only a rock”—a startling claim, since anyone could see that there was a woman in the moon with a child on her back, weaving a basket.

Speculation on the conflicting empirical realities and how they might be reconciled would become a regular fireside pastime on Sabarl. Every child was familiar with some version of the mythic narrative of how old woman Dedeaulea had come to occupy the moon, and the narrative could only be “true” (lihulihu suwot): it carried a visible cosmic signature. By contrast, the story of how American men had walked on the moon was recent history, little more than hearsay before Soter delivered eyewitness news from Port Moresby. Given that material evidence always had the last word in the matter of truth claims, this was a moment of cultural, not to say cosmic, dissonance. But for me, Dedeaulea Moon has the stronger claim to relevance in the contemporary moment. For it is she who converts cosmos to commons—she “furnishes” the cosmos, as Alberto Corsín-Jiménez argues for the epistemic objects (material and conceptual) that “furnish the commons” of occupying social movements, with what I’ve come to think of as a feeling-thing for collective reflection.19

The versions I collected of the Dedeaulea myth begin with a scenario of willful cosmic consumption and human violence. The moon (wahiyena), under cover of darkness, has been stealing the cooked red fruit that women have placed inside their baskets. Finally, the moon is caught in the act by a woman spying on the scene. The woman picks up a stick and attacks the thief, breaking the moon into pieces. Afterwards, an old woman, Dedeaulea, spots one of the glowing shards on the ground and uses it to light her way to the garden as night approaches. Noticing how she is leaving the village at night and returning in the daytime, her son-in-law suspects she is a night-flying witch. Offended, Dedeaulea leaves the family home, climbs a casuarina tree (known locally as the “witch tree”), and steps into the moon, taking her granddaughter with her. There she remains, weaving her basket, “striking” women once a month so that they bleed, threatening storms and flooding tides when she menstruates (which shows as a red ring around her), and without warning, sending out white-hot packs of flying witches, visible as shooting stars, who wreck canoes and feed on the flesh of their crews.

Now, as a morality tale—what Malinowski appreciates as a charter for social action—the Dedeaulea myth is lapidary with guidelines and messages of right and wrong action. At a glance, there are the consequences of negative reciprocal exchange, of transgressive feminine consumption, of possessiveness and retributive anger and audacious inversions of “natural” orders of gendered work, and of masculine responses to these—all encoded in transformations and displacements that would warm the hearts of hardcore semioticians. The vocabulary of symbolic forms is elegant also: at the most elementary level, Sabarl recognize images of red fruit foetuses, of basketry wombs, of first- and third-generation termini of matrilineages.

The text warms the hearts and minds of students of nature-culture interdiscursivity as well: we learn of humans and nonhumans positioned as interchangeable co-actants in exchanges that both produce and threaten their ongoing relations, and also their distinct worlds—and not just by way of anthropomorphism. Each entity naturalizes the other’s capacity to engender feeling that both transports social action and transforms social relations.

When Soter scientized Sabarl Moon, he of course proclaimed the de-feminization of the brightest agent of calculated transgression in the cosmos—its coolest operator. Abstract this capacity and the moon is indeed “only a rock,” as barren to Sabarl islanders as Lévi-Strauss imagined it to be, other than to itself: again, neither good to think, nor good to feel with—much less to feel for.

But to the extent that this new information performs an expansion of the commons to include remote entities and environments—for example, extraterrestrial fields of possible relations, or for that matter a scale of world so tiny that only technologies of trance or things like modern instruments of observation can access it—new questions emerge which at their most radical seek accountability and remediation for a world of diminished meaning, but also, of fewer ways of feeling.

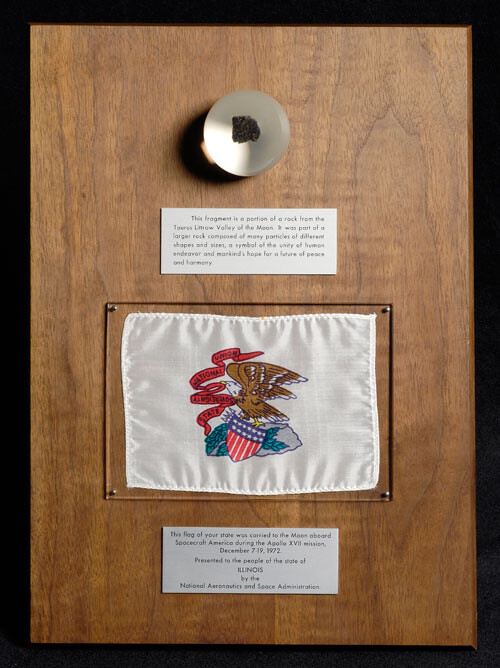

Listening to Goodwill Moon

Samples of moon rock first began touring the world at the conclusion of the Apollo program, in the mid-1970s. As “goodwill rocks,” they were artifacts, in effect, of US diplomatic agendas. Port Moresby, via the Australian National Museum, was on the itinerary for one such rock (NASA has lost track of many of the others, as have the recipients, and is currently trying to map their locations). But the moon rock’s social life in diplomacy had begun before the point of gifting it across the globe to heads of state and museum directors—it began on the moon. Prior to the final Apollo 17 moonwalk, astronaut Eugene Cernan, the last person to walk on the moon, joined his colleague Harrison Schmitt in requesting permission to return to earth with a “very significant rock” from the valley of Taurus-Littrow. Notice how Cernan’s argument to mission control builds to the point of conveying “the feelings of the Apollo Program”:

The rock is composed of many fragments, of many sizes, and many shapes, probably from all parts of the Moon, perhaps billions of years old. But fragments of all sizes and shapes—and even colors—that have grown together to become a cohesive rock, outlasting the nature of space, sort of living together in a very coherent, very peaceful manner. When we return this rock or some of the others like it to Houston, we’d like to share a piece of this rock with many of the countries throughout the world. We hope that this will be a symbol of what our feelings are, what the feelings of the Apollo Program are, and a symbol of mankind: that we can live in peace and harmony in the future.20

To state the obvious, this rock has a lot packed into it. For one thing, Gene Cernan has notably anticipated Latour’s call for scientists and social scientists to take up a diplomatic role in making peace with the cosmos, in its terms.21 Then again, the moment Cernan acknowledges the significant craftiness of the extraterrestrial rock, he liberates its poetic capacity for cosmic bricolage to model a properly cosmos-warming cosmopolitics. But his action also implicitly argues against military designs on the cosmos, which the scientific arm of the space program and as well the international effort to shape guidelines for peaceful uses of outer space were and are dedicated to implementing. To pick up a point I am grateful to Alberto Corsín-Jiménez for calling to my attention from art historian Svetlana Alpers on seventeenth-century painters who were aware of social conflict surrounding them but instead of painting about conflict “painted out of conflict,” this rock instantiated for Cernan the praxis of human-space contact crafted as event-time out of cosmic time. And here Corsín-Jiménez moves to the point in commenting on Cernan’s gesture:

The painterly pacific, in sum, is an account of how forms of pacification often require handling the materiality of strife: the pacific is the moment of warmth that extends and elates across pigmentpainter (nature-culture).22

In short, as a diplomatic engagement, this gesture portends a cosmopolitical double-take. In one direction, the rock’s displacement serves the cosmic diplomacy that Cernan envisions, namely, the distribution of a sublimated nature-culture denizenship.

Yet removing the rock from its altogether natural context recalls colonial collecting practices driven by presumptive rights of extraction: the gesture is vulnerable to being pressed into service of interests that include mining the moon for minerals, for example, and more generally to fusing the warp speed sovereignty of the space race with global capitalism.23

Here is the Goodwill Rock as it actually traveled across the globe:

One can only wonder what in this display persuaded Soter to report that the moon was “only a rock.” Whatever we might speculate, the evidence of matter out of place, and what Viveiros de Castro terms “time out of joint,” conjoin to unsettle cosmic diplomacy—to say the least.24

At the moment of its conceptualization, in situ, as a Goodwill Rock and testimony to human-moon “being there,” the moon rock opens to the structural irony of a future in appropriation that requires its destruction, and exposes its vulnerability as a goodwill onto-dispositif.

Venus and the Goodwill Moon abstract questions of cause and effect for attributing science a purity of detachment from sociopolitical violence—the first as an extension of dominant-culture values, the second as a nation-making gesture of altruism—whereas Sabarl Moon returns attention to the affective entailments of violent acts which concern not so much the technological apparatuses of violence (shattering the moon with a stick or shattering a reputation with words) as consequences for humanity of destroying the divide between temporal orders: of allowing event-time to become naturalized as if it were an eternal world order, and inaccessible to diplomacy. This is the promise and the threat of global mediascapes. This is what Starling’s Black Drop exposes by demonstrating that, celluloid and personal or digitalized and programmatic, “pure data” is insufficient to the production of cosmos as commons. This is what the Karrabing project contains, against the social and cultural forces of dissolution.

Warming to Cosmic Diplomacy

To put it crudely, human and nonhuman actors appeared first of all as trouble makers.

—Bruno Latour25

Eugene Cernan’s own vision of the moon in its capacity of partible circulation was an act of deterritorializing nature, but also cultures of expert knowledge; it opened to dialogue with local knowledge cultures expert and otherwise. With this, we are back with the Amazonian shaman, who would I’m sure recognize this cosmopolitical alliance and its capacity to make feeling things travel for activating public spheres of debate, policy-making, and resistance—another order of business, of course, but one attuned to the sensibility for diplomacy that cultured nature equipped for finding a commons in the cosmos. And as Soter saw the issue in apparently coming face-to-face with an alternative to Sabarl Moon, troublemaking is not the enemy, so much as an invitation to worlding otherwise than we have been, in the service of a warmed-up cosmopolitics.

Simon Starling, Black Drop: Ciné-Roman, text by Mike Davis and Simon Starling (Milan: Humboldt Books, 2013).

For far richer descriptive context, see Nicholas Thomas, Cook: The Extraordinary Voyages of Captain James Cook (New York: Walker Publishing Company, 2003).

“Review: Black Drop,” The Oxford Culture Review, March 18, 2013 →.

Thomas, Cook.

Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, “The Forest of Mirrors: A Few Notes on the Ontology of Amazonian Spirits” (paper presented at the symposium La nature des esprits: humains et non-humains dans les cosmologies autochtones des Amériques, convenor F. Laugrand, sponsored by the Centre Interuniversitaire d’Études et de Recherches sur les Autochtones, Université Laval, Québec, April 2004).

R. D. Haynes, “Dreaming the Stars: Astronomy of the Australian Aborigines,” Interdisciplinary Science Reviews 20.3 (1995): 187–197.

Elizabeth Povinelli, “Geontologies: A Requiem to Late Liberalism” (keynote address at The Anthropocene Project: An Opening, January 10–13, 2013, Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin).

Ibid.

See Bruno Latour, The Politics of Nature (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004).

See Rafael Antunes Almeida and Debbora Battaglia, “‘Otherwise Anthropology’ Otherwise: The View from Technology,” culanth.org, February 24, 2014 →.

Viveiros de Castro, “The Forest of Mirrors.”

Goetz Hoeppe, “Working Data Together: Accountability and Reflexivity in Digital Astronomical Practice,” Social Studies of Science 44.2 (2014): 243–270. This idea is also commonly pointed out by Lorraine Daston (“Objectivity and the Escape from Perspective,” Social Studies of Science 22 [1999

Ibid.

Quoted in Scott Atran, “A Memory of Claude Lévi-Strauss,” Huffington Post →.

Simon Schaffer, “Understanding (through) Things” (paper presented at the conference The Location of Knowledge, convenor Simon Goldhill, Centre for Research in the Arts, Social Sciences, and Humanities, Cambridge University, March 2013, page 4).

Marilyn Strathern, “Shifting Worlds” (paper presented at the workshop Emerging Worlds, convenor Danilyn Rutherford, University of California at Cruz, Department of Anthropology, 2013).

Schaffer, “Understanding (through) Things.”

Adam Robbert, “The Mischief and the Manyness,” Knowledge Ecology, April 21, 2011.

Alberto Corsín-Jiménez, “Three Traps Many” (paper presented at the Sawyer Seminar: Indigenous Cosmopolitics, convenor Marisol de la Cadena, University of California at Davis, 2013).

“Where Today are the Apollo 17 Goodwill Moon Rocks?,” collectspace.com →.

Latour, The Politics of Nature, 451.

Personal correspondence, June 15, 2013.

See Benjamin Noys, The Persistence of the Negative: A Critique of Contemporary Continental Theory (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2010).

To quote him more fully in the context of his paper with Deborah Danowski on “Anthropocenographies”: “Time is out of joint, and it is running faster. This metatemporal instability is such that virtually everything thatcan be said about the climate crisis becomes, ipso facto, anachronical; and everything that can be done about it is necessarily too little, too late.” Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, “Anthropocenographies” (paper presented at the Sawyer Seminar: Indigenous Cosmopolitics, convenors Marisol de la Cadena and Mario Blaser, University of California at Davis, June 8, 2013).

Latour, The Politics of Nature, (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004), 81.

Acknowledgments: My appreciation to Marisol de la Cadena and Simon Blaser, convenors of the Sawyer Seminar on the topic of Indigenous Cosmopolitics, for the invitation to present these comments in draft in June 2013. Also, I am grateful to Alessandro Angelini and Nicole Labruto for drawing my attention to Simon Starling’s Black Drop, which I was able then to experience at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art, before writing the final version of this paper.