Once Upon a Time

Hamlet is seated on a throne. He’s bent and wasted. An imperfect Hamlet, frozen in place; history stretches between him and us like an unbreachable wall. His left hand holds up a fallen brow. All is dark around him. Foreboding. Tenebrous. The only light on the set is absorbed by the deep furrows on the prince’s hands. This is the wrong way for a film to start.1 From the very beginning, it forces us to retune our understanding of the subject, to perk up in disagreement. As a growing sense that things are heretically amiss begins to take hold, a dramatic piano pumps life and suspense into the tableau. The camera zooms in. This confirms that our prince is the sexagenarian his deeply grooved leather-skin suggested. It also pegs other qualities to him, at least through the grain of the pirated version of the movie that we are watching. Something of the lugubrious old pervert, for instance. He raises his head, puts deep and penetrating eyes on us, admonishment for our audacity in thinking him any less a prince than other Hamlets. We take note of the cheap costume he is in. It renders him more jester than royalty, and ratifies that he is a counterpoint to the healthy young Hamlet, a bit melancholy but all the more attractive for it, that lords over the literary imagination of the West, indexing its supposed universality. Between these two Hamlets there can only be a strained relation. One that parody or deliberate misuse underwrites. It is never the young and vigorous Danish monarch who represents what is rotten in the kingdom. We cannot be quite sure this is the case with the flabby flesh of our Cuban lead. One can imagine a whiff of decay coming off him; the concoction of gases that churns in the carcass on the side of the road finds liberation through his pores as death slowly slurps the marrow in his bones and ravenous flies wait just outside the frame. A bit senile, this aged Hamlet even botches the question. “Are they or are they not?,” he asks with pointed disdain. An old bag of bones defiantly putting a challenge to the audience.

¿Son o no son?—That is the question. The first thing one has to ask is what sort of question is this, imperfect as it sounds to knowing ears, if not altogether grating and blasphemous. What is it referring to, beyond the words it misquotes? Who are these son, these “they”? Is it the Cuban people who have entered a divergent historical pattern? Is this a Hamlet with social concerns, slightly disenchanted with the timid social function that mass media and artists have surrendered to in the new society? If he’s mourning anything, then, it may be an opportunity that is being wasted. Or is the question imperfect in more ways than one? What if it is untranslatable in that it is asking about musical genres whose names have no equivalent in other languages, about rhythms pried free from the bones of dead animals? What if it’s posing an inquiry about the Cuban son, that most foundational of genres? The question ¿Son o no son? is then closer to something like The blues or not the blues? It has to do with popular music and shared experience, and not with the metaphysical inquiries that trouble the humanist or bourgeois subject—nor even with the theoretically crafted concerns for the collective that shape the unbendable militant.

Or maybe Son o no son—as in, are the methods employed in the film able or not able to do what García Espinosa needs them to do? ¿Son los que tienen que ser o no son? is a way of wondering if the contradiction between autochthonous popular culture and a transnational film industry, if the exercise of rubbing one against the other, is fruitful. The film finds its shape as variations of the titular question. Figuring out which version of ¿Son o no son? aligns with what Hamlet intended is, then, less important than the fact that the inquiry keeps itself suspended over multiple possibilities, refusing easy disentanglement from indeterminacy as a way to propel a reflexive drive to the very end and at multiple levels.

However unstable the meaning of the question may be, our sorry Hamlet is as dramatic in his delivery as any member of a teatro buffo troop would find it proper to be, professionalism making its claims on all citizens of the stage equally. He strains his gravel-in-the-throat voice, sounding more like a goat than an actor, but graced with a certain Caribbean flow nonetheless. It’s the paradox of guttural mellifluousness that renders old tobacco smokers so charming. His way of asking the question reminds one of that other botching of it. “Tupí or not Tupí?” asks Oswald de Andrade in his Anthropophagic Manifesto (1928), alluding to the deglutition of Pedro Fernandes Sardinha, Brazil’s first bishop, by the Caeté Indians, a part of the Tupí people, in 1556. Does the otherwise—which is what these pages are about—not emerge and endure with the consuming and digesting of the alien, with rearranging a corrupt state of things that we can never quite line ourselves up with? And what is as alien to us nowadays as the strange and savage ways of Portuguese conquerors must have been to the Tupí in 1556 if not an economic “intelligence” that has reformatted the planet to serve the illusory goal of its infinite perpetuation, based on the fantasy that the resources at its disposal are endless? Or is it, as experience confirms, slightly different than this: Is the otherwise precisely that which emerges from a missed encounter, the fruitless exchange, with the alien? We try to find new potentialities in immaterial labor and other novel things that Capital may have generated, we test practices that may lead to an immanent derangement of things as they are, but the freedoms come to meet us are so shamefully small and so easily recaptured. We try to swallow the alien but it turns out that it digests us instead.

In order to anchor things to their historical moment, one has to be mindful of the fact that if our abject Hamlet is connected to a manifesto, it’s to one that was published forty years after de Andrade’s, in the midst of a revolution that wasn’t only aesthetic: Julio García Espinosa’s “For an imperfect cinema.” “Nowadays,” that text begins, “perfect cinema—technically and artistically masterful—is almost always reactionary cinema.”2A perfect prince with his perfect question may be a stand-in for a contingent unity of the world that power sustains and naturalizes, not the least through reactionary cultural production, in order to favor those who wield it. We should keep this in mind as our Hamlet sets off on his monologue: “What is better for the spirit—to suffer the blows and barbs of misfortune, or to take arms against a cluster of calamities and, taking it head on, put an end to it? To die. to sleep.” Cheated of a grave skull to address, our prince leans his head against the large jawbone cradled in his right hand, and continues: “Maybe to dream.” He strikes the bone with the back of his fist. Clack. He looks up, to where one could think God or the director would be, if such reassurances were still believable and consoling. “And for you to think, Shakespeare, that with a simple dream we could put an end to all our sorrows.” He looks at the bone again. “To die, to sleep. To sleep! Here we find fear of an existence that stretches so long in misfortune.” Hamlet rises threateningly from his throne. He advances under a spotlight that he commands to follow him through the sheer and hypnotizing disdain lodged in every step he takes. He grunts words that we can no longer tell whether they are his or García Espinosa’s: “Who can endure the outrage of so many stupid songs and soap operas when one can procure for oneself eternal sleep with a simple dagger? But Silence! Shhh! The beautiful Ophelia approaches. Nymph, in your prayers remember The Entire Son.3 Hahahaha.” He strikes the mandible. “¿Son o no son?—That is the question.”

There is no symmetry here. The words we are hearing find no echo in our recollection, even as we have enough clues to plot things in the proper location. We know this play, even those of us who don’t quite know it by heart. “I could be bounded in a nutshell / Yet count myself lord of infinite space / Were it not that I have bad dreams” … and all that. We know it by ear, let’s say. We pick it up when we hear a bit of it. It’s in our cultural DNA; it climbs out of there as much as it comes from the actors who may be speaking the lines. It gurgles in our depths. And yet, every word uttered and every gesture enacted by our pruney Hamlet, obviously disarticulating the very role he has appropriated, marks a distance from familiar things, courts a certain disunity. The wrong body. The wrong attire. The wrong sort of defiance. The hoarse voice. Vehemence replaces sorrow. Fury displaces brooding. The absent skull. In its place, a mule’s mandible. Our Hamlet strikes it repeatedly. To every blow the bone responds with a sound. Lacking organic tissue to fix them in place, the animal’s loose teeth rattle and echo in the concavities of the bone. Music begins to take shape. Music from the other side. Entwined with death, yes, but also with Africa. We understand this in our bodies. This is also in our DNA. But it’s more than this: because what the jawbone ultimately points to is a shift in cultural register. We’ve left the heights of fancy literature and have been deposited in the very heart of vernacular culture, of expressive particularities that refuse us the possibility of automatic decipherment that canonized artifacts allow.

Is Son o no son an instance of the otherwise, an exercise in undoing a unity of things that has been naturalized by power? Is “imperfect cinema” the form that the otherwise assumes in filmic space at a particular moment, against the treachery of a cinema of quality and the social order that sustains it? Does an imperfect cinema not already announce the alienness—the end—that stalks a neocolonial cinema of quality from the future? “What happens if the development of videotape solves the problem of inevitably limited laboratory capacity,” asks García Espinosa, “if television systems with their potential for ‘projecting’ independently of the central studio render the ad infinitum construction of movie theaters suddenly superfluous?” What happens, we can add, when the digital overruns the world of celluloid and entire films can be produced on a cell phone and distributed on platforms of nearly global reach?

What happens then is not only an act of social justice—the possibility for everyone to make films—but also a fact of extreme importance for artistic culture: the possibility of recovering, without any kinds of complexes or feelings of guilt, the true meaning of artistic activity. Then we will be able to understand that art … is not work, and that the artist is not in the strict sense a worker. The feeling that this is so, and the impossibility of translating it into practice, constitutes the agony and at the same time the “pharisee-ism” of all contemporary art.4

Facebook Uprisings

In the same way that we associate Shakespeare’s Hamlet with a human skull, after viewing the first few minutes of Son o no son we cannot unbind Garcia Espinosa’s Hamlet from the mandible of a sterile mule. The repurposed jaw as a musical instrument is found in numerous cultures. Caribbean, Peruvian, and Mexican musicians have all employed animal jawbones to produce the rhythmic baselines of different genres. The bone is stricken with both the palm of the hand and the backside of the fist in order to generate different sounds. A thin branch or a lamb’s rib is also dragged across the teeth. The drag and the thump, establishing a rhythm, often replace or accompany traditional drums in popular songs. To be able to use the fragment of the dead mule, it is necessary to first whiten and soften the bone with alcohol baths and by exposing it to the sun. It’s as if the calcareous material needs to be freed of death’s vapors for its afterlife-as-percussion to shed its shyness and step out of tenebrous silence. Colorful strings or thin reeds are woven into the front-most juncture of the bone to avoid that it be fractured by the constant striking, while also beautifying the instrument, binding beauty to function, function to death, death to undulating and sweaty bodies—things that often miss each other in thinking. This decorating of the animal’s chin is an allegory of the relationship in the Caribbean imaginary between the notion of repurposing and the fatal end of things, acutely underscored by the fact that we are being set to dance by a fragment salvaged from a dead beast.

Doesn’t the mule announce a path to a dead-end? Donkey and mare, animals distinguished by the number of their chromosomes, 62 and 64 respectively—a small difference that makes all the difference—are gifted with a completely sterile descendent. Biological forces close the path for what has been spawned. But it’s also true that, while being an atrophied creature, an appendix-like protrusion in the smooth trajectories of two different species, the mule has significant effects in the world. In the first place, the mule hauls behind it entire agrarian economies, and it does this precisely where other methods of transportation fail. Whether it’s moving coffee or coca or cacao, the mule is part of the economic flows of very productive regions throughout Latin America. And it isn’t just a question of replacing more technologically advance methods of cargo. In its travels the mule unintentionally participates as much as the deliberately swung hoe in the farming itself. Through its feces, it fertilizes the mountainsides that are favored by coffee growers and in this way is incorporated into of one of the most desired crops on the planet. What makes this crop so coveted and special, those addictive aromas that eventually envelope us when its beans finally brew in our kitchens and cafes, has been in part determined by the mule’s gastrointestinal residue. The animal may stretch itself in space through its waste, but it remains bereft of the capacity to reproduce. It’s a limit.

Isn’t Son o no son like a mule—useful, vital, indispensable at a particular moment, but somehow sterile in conditions it didn’t arise from? It’s as if the possibility of the otherwise is at the very same time the otherwise’s condemnation to infecundity. Doesn’t the otherwise announce a path to a dead-end, sterile as it is in generating any effects beyond the context in which it emerges, infecund after it crosses that line at which the very material and social conditions that demanded it have changed? Isn’t this one of its structural limitations? Instances of the otherwise may come with built-in obsolescence, just like appliances; with expiration dates, like milk. And if the otherwise is going to be an important concept or category through which to understand practices that may divert us from the actual state of things, doesn’t it behoove us to understand these limitations? Isn’t the otherwise, the event or the practice that reminds us that another world is possible, not the very same thing that reminds us that we need to historicize our production? This is one way it clamors for an acknowledgment of its specificity and of the radical difference between its context and ours, priming us to be of service to our moment and not to the memory of practice whose time has passed.

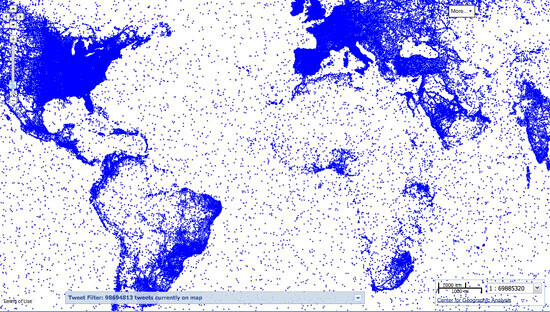

Perhaps this is why Son o no son begins with a ruin of Hamlet—he allegorizes the transience of the truths that are being presented, the inextensible shelf life of their usefulness. It’s like a play mourning the finitude of its necessity. The otherwise is born with its coffin sitting beside it. This is underscored by García Espinosa’s own awareness that his films were not specimens of a truly emancipated cinema, but efforts to clear a path toward it. And as such, of limited use, coursing toward the dead-end that furnishes them with significance. Aren’t instances of the otherwise, then, once they are properly historicized, what remind us that returning to the farm and the simple life, that making the imperfect revolutionary filmic essay, that producing tiny economies invested in a wobbly ethics of sharing, that going back to tactics we’ve inherited from the 1960s or the 1970s, that dreaming the Tricontinental dream, that eating Europeans or celebrating this liberating cannibalism may no longer be what is needed? All these things had their moment and now we must tune in to our times and see what emancipatory possibilities and difficult challenges these offer. We need to be extravagant in the demand for our instances of the otherwise to be utterly contemporary. We need to be obstinately demanding in this. The mule’s mandible is now an app, and its noises are vectorialized through massive infrastructures. The otherwise, in our midst, has to grapple with scale. It has to find in things like privatized transnational platforms and global logistics the targets of its counterlogic and negation. New state apparatuses have become available through algorithmic manipulation. This is what it has to be alien in relation to.

(It may be even more complicated than this in this age of mega-systems. Perhaps the otherwise, as a truly disruptive force, is something we can’t generate anymore or even see coming. It emerges from the excesses and glitches in these systems, or from the planet retaliating against our wanton destruction. Maybe the otherwise nowadays is a rising sea that instead of attacking through the beach, like the Allied troops, climbs up through the limestone and floods the city from the center out, obliterating any sense that may have organized the regime of private property; or it’s the volcano’s model-defying massive ash cloud that paralyzes an entire continent and its markets; or its the earthquake that unleashes tsunamis in multiple directions at once, annulling whatever precautionary measures we may have taken and washing away the illusory distinctions that subtend our retrograde nationalisms.)

Pessimist’s parenthesis inserted, let’s get back to what we were saying. Historicized, instances of the otherwise may have a residual function, something that we can tease into significance by approaching them with a contrapunctual gaze that, while marking an absolute difference between the two states, may show us what they were good for as vital practices and what their possibilities may be as dead and sterile things. We can zoom out here, see things in their proper place, but also see what they can do from their state of exhaustion, rescuing some of their effectiveness from wholesale nullification. They can return as archival material, as counter-memories to what the present values, as the content of repressed genealogies, as zombie music of encouragement, as lures to refuse uncoupling our thinking from actual circumstances, as reminders to renew our fidelity to justice, as dispatches from other desperate times that summon us to be ambitious and quarrelsome in our engagements with the world we have been sentenced to. They can be models, but not in themselves. Only in their quality as being gestures that were in consonance, that were militantly synchronic, with the problems and demands of their conjuncture. In this way, we mediate the otherwise’s unavoidable sterility into something useful; we turn the dead mule into a rhythm we can employ again in ways that may have never been apparent while the thing still had life in it.

Un-historicized, on the other hand, instances of the otherwise encourage replication. Or rather, we are prone to repeat them having misunderstood their limitations and knowing their formulas. And as repetition, instances of the otherwise are fetishes. They ineluctably simplify the social relations and material conditions that they claim to be rising against, as much as remain blind to what such a rising up entails. Un solo palo no hace monte: to repeat something because it worked once, to leave an unsubstantiated “transhistoricalness” unquestioned, doesn’t add much to anything. Putting hammocks and swings in an empty lot; parading with sandwich boards on which we have laid out our complaints; inviting disenfranchised kids to karaoke; casting shovels out of a minuscule percentage of the obscene quantities of weapons in conflict-ridden territories; turning favelas into advertising for Sherwin-Williams—what is any of this for? What does it do? Does it do more than remind us of things that have already been tried, probably in situations in which they made more sense? Do they do more that tell us that their producers belong to the progressive camp that hates the commodity?

An important concern with repetitions of instances of the otherwise, of efforts tuned to the needs of other times, is often that the reach of their contestatory power, the circumference of what they affect, is insignificant in relation to the global forces that swirl around and even through them. The implications of their existence are symbolic above all. We need to generate social imaginaries that do more than rehearse the ones we were reared in, and produce things that are of consequence in actualizing them. Social media uprisings and the democratization of cultural production feed corporate Big Data appetites, as much as they do anything else. Contemporary art is the beauty mole of finance capitalism. These days, the dreams of an imperfect cinema, betrayed by history’s vicissitudes, resemble Google business plans: they both pine for more and more producers. It is here where we begin.

The problem with duplicating instances of the otherwise, of using spent languages and strategies, is that as reproductions they are diachronic, unequal to the magnitude of the problems they face, and often saturated by nostalgia. They address arrangements of things that are no longer in place, rallying against the ghosts of problems that belong to circumstances we no longer find ourselves in. They seem, as ultimately aesthetizations of contestation, ready for reincorporation into the prevailing logic, fully prepared to be in marketplace competition with other forms of supposedly more reactionary cultural and political production. To claim that they are world-making, the way that the things they model themselves on may have been, is to indulge in inflationary rhetoric. It’s more honest to say that, at their best, responding to contextual necessity more than to theories of capitalism’s evolution, they alleviate the real economic and existential pressures of certain populations. And this is not without value, but it is not a blow to the status quo. Disentangled from providing immediate relief, these diachronic instances of the otherwise are academic exercises, endowed with a counterfeit validity extended by the people involved in them and by the usually rarefied quarters in which they unfold—quarters in which everyone seems frightened of thinking in terms of the social totality, lest they come off as retrograde champions of “master narratives” or whatever. These instances of the otherwise are not a challenge to the state of things as much as an oblique reflection of a fragmented social life, reinforcing more than refusing the supposed impossibility of thinking our way through and beyond existing conditions. They put nothing in crisis, and often take up space that could be occupied by something other than hasty reproductions at risk of egregiously embodying a sham antagonism. These repetitions are ameliorative at best, and only important when they ameliorate real needs, when they displace burdens that leave their mark on disenfranchised and uprooted bodies.

It is only when we put Son o no son, “For an imperfect cinema,” and other instances of the otherwise through a historizing operation that they can begin to be employed in a contrapunctual thinking that may revitalize them as counter-memories and material for alternative archives. It is only then, as sterile and reanimated at once, that they can serve as points of contradistinction not so much to the status quo but to the instances that seek to contest the status quo—a kind of metric with which to measure the effects that an event or a practice generates. Do these new exercises have the reach, contextual differences considered, of the exercises they are being compared to? Do they speak with efficacy to their moment? Does a monument to a dead thinker in the projects, taking into account all it does, for instance, have the same impact as anything associated with Third Cinema? It’s not a question of fetishizing what has passed, but of using it. It is only then that the otherwise, too, becomes like the mule in its afterlife, which even after it has been fully drained of vital forces, unleashes the euphoria of the dancing mass. It does something, and it’s something different than when it was alive. Sterile in life, it now populates certain spaces with sexual energy; it lubricates heated contact. The animal’s shaken and stricken jawbone may provoke in the deep nights that shore up at the edges of the Atlantic a hurricane of muscular distention. The mule’s teeth tremble in the dry bone, as deft bodies twirl to their contagious racket. After an exhausting day, catatonic coca leaf and coffee bean growers begin to sense, settling into the recurrent clacking, a zombie music climbing into their bones. The mule’s mandible tunes sonorous rhythms to hormonal rhythms as dancers loose themselves in the moment and in each other. This is not to say that the mule is alive again, or fertile, but that it can be contrapunctually revitalized, put to uses other than the original ones we may have devised for it.

We are referring to Julio García Espinosa’s Son o no son (1978). The fragments of Hamlet’s monologue come from the first few minutes of the film.

Julio García Espinosa, “For an imperfect cinema,” Jump Cut, no. 20 (1979): 24–26 →

This alludes to the genre of the son, but refers more directly to the title of Nicolás Guillén’s 1947 poetry collection, El Son Entero.

García Espinosa, “For an imperfect cinema.” Translation slightly altered.