The Shell In The Mountain

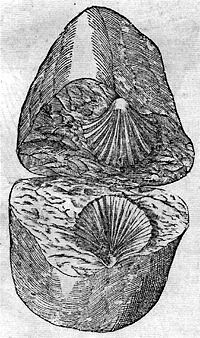

The theories of natural science that were nascent in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries may be re-excavated through the figure of the marine shell—encountered as a form of stone, and lodged mysteriously in the highest mountains of Lower Saxony. These stone shells (as well as eels), Voltaire said, “made new systems blossom.” A cacophony of eminent philosophical and scientific voices entered to contest the origins of these aberrational geotic forms, summarized in Anton Lazzaro Moro’s 1740 excursus Opinions On Marine-Mountainous Bodies (De’ crostacei e degli altri Marini corpi che si truovano su’ monti).1

Moro (1687–1764) theorized the postulations that such “shells” had been carried to mountain summits by the winds, or were perhaps birthed from a parent rock with a particle seed as “tricks of nature.” Another proposition held that fishermen bearing crustaceans ate the flesh inside and left these exoskeletons to petrify into rock. And yet, whether the Great Deluge or other massive oceanic outflows that encased aquatic bodies in the upper echelons of the earth, this entrapped meeting between the positive of the mountain face and the negative of the shell raised universal questions of land-sea relation, of the land “trying to rival the sea in fertility,” and of the alchemical quest for casting a molten biography of the subterranean.

Amid this controversy over earth-history, the incipient fields of geology and stratigraphy were joined at the interface of reflections on cosmogony, metaphysics, and a return to alchemical hermeticism. A problem of origins and nativity formed the key point of contention. Did the shell properly belong to the mountain as its geologic kin, or had it arrived from an elsewhere—as an “anti-object” imprinted as a marker of ancient displacements of sea and land?2

These disputes reached a point of fissure in 1644 when Descartes’s Principia Philosophiae established a mechanical, materialist account of the origins of the earth. In this near-heretical telling, the sedimentation of potentially infinite terrestrial particles coalesced in a vault of boundless time. From this basis, Danish Catholic bishop, anatomist, and geologist Nicolas Steno (1638–86) conjectured in his 1669 Prodromus that Glossopetrae, or “tongue stones,” were in fact petrified sharks’ teeth. By this reasoning, they had preexisted the sediment surrounding them in a formation that was successive rather than simultaneous. “How unanimously they come together in agreement,” he exclaimed of the manner in which water virtually held the soil, of how mineral sediment that was lodged in “muddy waters” solidified and shaped the fossil shell, and of the mountains accumulating after the mollusks. This move was then one of temporality but also of matter—transmuted from softened oozing particles into solid mass.

In a revivalist effort of the Classical Hermetic vision, German Jesuit Athanasius Kircher (1602–80) advanced a thesis that supported such an aqueous history of rock formation, although one that maintained the divine hand of creation. His “Subterranean World,” or Mundus Subterraneus (1665), was a globe governed by fluid systems of water and fire arising through flows of vis lapifidica alchemically reacting with niter, alum, and vitriol. Drawing upon English physician William Harvey’s recent description of the human circulatory system, the earth was figured as a respiring, arterial being. Fossil shells were hence grown of the earth, not entombed in dead stone. As “tricks of nature,” their near inexplicable presence indicated sublime systems of meaning—cosmological truths hidden behind the veils of outward form.

Across generations of naturalists whose thought-models were rational, cosmological, and geopolitical, the fossil shell remained a cryptographic document to unlock a deeper archive of the “natural world”—to tell of a primeval time when the oceanic realm was a ground that bedecked both deserts and mountains alike.

The Cave Image as Living Testimony

In the Kimberley region of North Western Australia resides a scattered site of caves bearing rock art that is likely to have origins in the Pleistocene era—the most recent period of mass glaciations, popularly conceived as the Ice Age. In the mode of the fossil shell, the figurations molded in these caves convey another perplexing concern in the conjectural pathways of planetary history and humankind: the testimonies of geologic time and the manner in which the earth may “speak” to its emergence.

These anthropomorphic “Gwion Gwion” or “Bradshaw” paintings mediate the threshold of human and nonhuman in the micro-biochemical transactions of “living pigments.”3 Whereas other cave paintings in the region deteriorated in a few hundred years, the Gwion Gwion figures maintain a remarkable vivacity—their original painted surface replaced and replenished by a biofilm of pigmented bacteria. Over millennia, crimson cyanobacteria have etched themselves into rock surfaces, generating minute channels that hold certain image areas separate from those inhabited by black rock-adapted fungi. They are thus true petroglyphs—stone-image assemblages of mineral, bacteria, time, and semiotic form.

Radically distinct from the more recent “Wandjina” images that are in part maintained by local Aboriginal groups, the Gwion Gwion images seem to gesture toward another civilizational epoch and a more complex horizon of antiquity. The efforts of Australian neurologist Jack Pettigrew to decipher the inner secrets of the Gwion Gwion images depend upon a hypothesis that weaves ancient human history with climactic change, a supervolcano event and patterns of human/animal/plant cohabitation.4 As geotemporal testimony, these paintings are estimated to date back to between 46,000 and 70,000 years ago, calculated by the extinction of depicted megafauna and the first appearance of the Australian baobab tree, which was derived from the African species. Pettigrew’s hypothesis links hallucinogenic visions in shamanic Tanzanian Sandawe rock art with the “mushroom head” figure of the Gwion Gwion caves as an Afro-Australian civilizational common of sense-perception. In narrating their migratory origin, he suggests an epic human passage across the Indian Ocean in reed boats, carried by Ice Age currents and sustained by the long-lasting nutrition of the baobab seed.

The Gwion Gwion remain impermeable to the metrics of radiocarbon dating. As such, they are living images that refuse to yield to the carbon paradigm of biopolitical finitude, as theorized by anthropologist Elizabeth A. Povinelli.5 They exist bound to the greater mountain, grassland, and waterway entities of the Kimberley region, along with the streaked deposits of coal and shale gas that reside beneath its skin. Here, earth histories are met at their material base by the speculative regimes of resource capital.6 The rock’s concave surface is hence refigured not as a primeval instance of the human imprint in “nature,” but as a future anterior where radical efforts of interpretation are wrought by the conflation of extinct and extant.

The Platonic cave allegory is overturned in Gwion Gwion rock art as the real object incessantly eats its shadow; the cause interpellates as effect and therein casts its image back into objectivity. In this organic state of “freedom,” the cave is set up as a time capsule propelled by microbacterial agents de- and recomposing ontology itself.7 The terms of life and nonlife in the logic of planetary governance are thus changed in this visual condition of Gwion Gwion rock art. Yielding a new kind of event-image grasped beyond the carbon limit—stretching the imaginary of an end-time and incessantly looping back as a regenerative figure that is self-resourced.

Turbulent Bodies

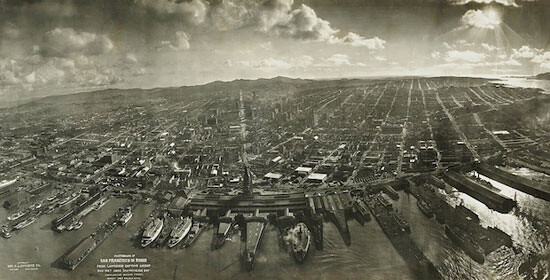

At 5:12 a.m. on April 18, 1906, a massive earthquake shook the Gold Rush city of San Francisco for less than a minute.

What does it mean to read the earth as a bodily matter amid a global network of advanced warning sensors that ceaselessly mine the planet as seismic database? The gripping finitude of an end-time imaginary performs its everyday repercussions in the California earthquake’s millenarian image. Here, a vast geoscience infrastructure and national security apparatus has grown around a collective apprehension of the turbulent contours of life along the San Andreas Fault. This massive tremor of 1906 nearly leveled the city. It left in its wake not only devastating residual fires but the embryo of the United States’ seismological bureaucracy, with a committee of twenty scientists charged to study the geological skins of California.

The apocalyptic configuration of the California earthquake continues to reverberate through televised imaginings of “The Big One”—in which a southern segment of the San Andreas Fault is anticipated to unleash unprecedented catastrophe and shake Los Angeles “like a bowl of jelly.”8 This zone of temporal-territorial premonition is where The Otolith Group (Kodwo Eshun and Anjalika Sagar) surveys California’s seismic psyche in their film Medium Earth (2013).

The camera conducts surface scans of the Southern Californian desert. It exists as a particle-terrain—a body-in-pieces. We become enmeshed in vast tides of scree and dust-storm currents. As rock formations come to the fore—striated, stitched, cracking, and withering—the voice-over narrates a tremor thus: “The ground becomes a seventy-second ocean.” The desert’s fluidity meets a stuttering lens that sets up the task of prospecting the fault line where it intersects with California highway Route 14. The state of transit is hence met with the transfer of earth stresses.

In this nonhuman cinema, the event of the earthquake is a generalized condition. The whorls of pressurized sediment act as a planetary fingerprint where geocorporeal palmistry may decipher an arid futurology. Beneath the “language of stones”9 lies the corporeal reportage of Charlotte King, an earthquake sensitive. Through acute self-monitoring, King discerns “aches and pains” as precursors to earthquakes, which arrive hours or even days later across the globe.10 Her being resides in radical complicity with the earth’s event sphere. If earth is a medium for human life, King is a mediator at the threshold of seismic knowing.

The question then remains, how might suffering manifest as aberrational phenomenon—not least as earth-image but also as impossible terrestrial formation? To borrow from Fernand Braudel, in what ways may landforms transfigure as events of interruption and be themselves “the dust of history?”11 Against the sedimentary backdrop of monopoly power, land may be found in circulatory appearances12 and as a force of eruptive displacement.

Dust, however, as it is usually perceived by us, is, like dirt, only matter in the wrong place.

—Alfred Russel Wallace in The Importance of Dust: A Source of Beauty and Essential to Life, 1898

The fault line is a form-in-crisis, yet also a limit-figure of human perception. How absurd then to launch an “archive of fault lines” upon which to assemble a total systemization of future warning. The notion of the event appears here as a conflated human and geologic horizon. Beyond the material limits of a death toll and destroyed habitus, devastation is received as another sort of negative, an aberrational form that subsumes the unseen below-ground to uphold the status of a floating signifier.

Perhaps Charlotte King’s extreme self-exposure crosses lines with the efforts of Kircher to decode the earth’s secrets by arranging to have himself lowered into the sulfurous core of Vesuvius. When the reassurance of a solid ground is refused, the measure of certitude lies beyond the reading of magnitude. Comprehending the seismic earth takes us to a meeting place between competing exterior scales formed in the presiding logic of the day and the dissonance of a bodily interior as geo-affective apparatus.

Is the Earth Still Our Ancestor? Or, a Necropolitics of the Mine

If one is not a human being, what is one?

—Achille Mbembe13

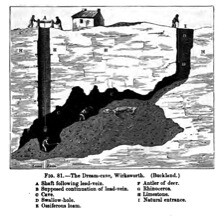

In the globalized economies of extractive capital, the fossils that propel consumption are no longer treated as living organisms. Rather, they become mere necrosed matter supporting the Cartesian hypothesis of the earth as an “extinguished star.”14 This same negation fuels an extractive imaginary of modernity, also conceived in the caves of Lower Saxony where land was remade as resource, serving paradoxically both the mobility of capital and the fixed territorial claims of sovereignty.

It is in these Harz Mountains at the close of the seventeenth century that Wilhelm Gottfried Leibniz (1646–1716) arrives at the fossil shell’s archaic fold of human and earth time. The great metaphysician had in 1685 been commissioned to prepare a genealogy of the House of Brunswick (Hanover) in support of Duke Ernst August’s claim to the ninth electorate of the Holy Roman Empire. In 1692, the Duke’s bid to investiture proved successful—Leibniz’s promised genealogy, however, had metamorphosed into a monumental preface. Rather than a lineage of nobility, it proposed a multilayered ancestry of the earth itself, dwelling on the genesis of rocks, the classification of minerals, and the organic origins of fossils. It also included a famed reconstruction of a fossilized unicorn.

Posthumously published, the Protogaea (1749) is an extensively illustrated treatise that supplants a territorial claim to sovereign inheritance with the planetary heritage of humankind. Its singular cosmogony arose from the annals of the earth as much as from the Duchy’s grand libraries. Like Georgius Agricola (1494–1555) and Pliny the Elder (23–79 AD) before him, Leibniz’s observations were gained through experimentation in the silver mines of Saxony and Bohemia—source of the Prussian Thaler, precursor to the dollar and chief “coin of account” of the burgeoning industrial economies of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Where Pliny had experimented extensively with hydraulics to extract gold from earth-veins, Leibniz devised elaborate wind-turbine systems seeking to permit year-round mining operations.

However, Protogaea was also to sow “the seeds of a new science called natural geography.”15 For Leibniz’s efforts stood at the time of the impending partition of geology from cosmology, of the extractive impulse from the excavatory urge, and of history from ancestry. And thus, Protogea also culminates the intrinsic ties between capital, the lineage of the nation-state, and earth-as-resource.

Gold is found in our own part of the world; not to mention the gold extracted from the earth in India by the ants, and in Scythia by the Griffins. Among us it is procured in three different ways …

—Pliny the Elder16

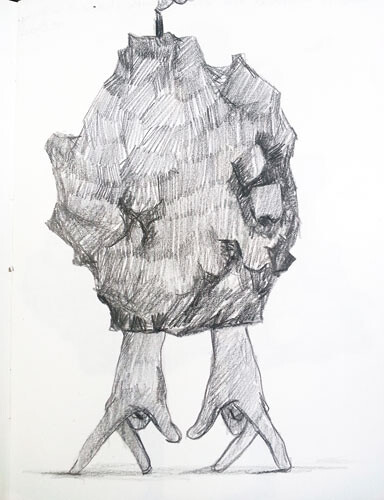

As released and roaming substance, the elemental presence of mineral wealth may be found enmeshed in the wanderlust of global capital. Artist Prabhakar Pachpute’s wall mural Land Escape (2014)17 may be said to situate itself in the aftermath of Pliny’s third mode of extraction, “where gold surpasses the labours of the Giants.” Belonging to a family that includes three generations of coal miners, Pachpute provides a new anthropomorphic vision for the mineral body. The skeletal frame of coal, or “black gold,” acquires legs to flee the land—to deny its existence as pure value—attaining a renewed life in a state-of-emergency. In the deathly matters of the mine, a flooded mine shaft may be transposed into a swelling lung as a lake of dust, and a giant mountain may morph into a putrid lake.

It is through the negation of planetary coevalness18 that the mine takes form as a necropolitical void, sitting within the mountainous “debris of the past”19 and yet within the accelerating temporality of industrial extraction. One loses all sense of an interface, encountering instead the limit condition of geography as the writing of “nonlife.” The unseen deep recesses of the mine only come into view as artificial residue or negative nourishment. As an ultimate subtraction, mining-as-event is one in which earth bones meet human bones to stage a pulverization of bioterrestrial history. If the earth’s insides are considered a bureaucratic storehouse holding the biodata of its manifold elements, the operative logic of the mine is the deletion of ancestry itself.

An excellent account of this converging history of science and philosophy is given in Paolo Rossi’s The Dark Abyss of Time: The History of the Earth and the History of Nations from Hooke to Vico (Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1984).

As architect Kengo Kuma notes, an “anti-object” is one that induces a reckoning with the external world through its inherent transgressability. See Kuma, Anti-object: The Dissolution and Disintegration of Architecture, trans. Hiroshi Watanabe (London: Architectural Association, 2008).

These “living pigments”—which subsist by cannibalizing former generations of the microbacteria—were identified in 2010 by a team of researchers led by Dr. Jack Pettigrew of the University of Queensland. See Pettigrew et al., “Living pigments in Australian Bradshaw rock art,” Antiquity, vol. 84, no. 326 (Dec. 2010).

See Jack Pettigrew, “Iconography in Bradshaw rock art: breaking the circularity,” Clinical and Experimental Optometry vol. 94, no. 5 (2011): 403–417.

The carbon imaginary is an analytic device advanced by Povinelli in approaching the impasses of theorizing biography (life descriptions) and geography (nonlife descriptions) within the conditions of Late Liberalism. It pinpoints broad-based political and subjective dependencies on metabolic imagery of birth, growth/reproduction, and death. This conceptualization will be addressed in the forthcoming Geontologies: A Requiem For Late Liberalism, the last in a three-volume enquiry into Late Liberal government and the potentialities of an “anthropology of the otherwise.” See also “Interview with Elizabeth Povinelli with Mat Coleman and Kathryn Yusoff,” Society and the Open Site, March 6, 2014.

In court challenges over the development of an AUD $40 billion gas-processing plant—the largest in the world—these caves and their icons must make testimony to their “value” in contestations with protagonists such as “the environment,” Aboriginal Traditional Owners, the voracious claims of the market, and Australian settler society. See “Gas hub: Controversy in the Kimberley,” Australian Broadcasting Corporation, April 12, 2013 →.

Here, the ideas and generous dialogue of Mihnea Mircan, with regard to the exhibition and research project “Allegory of the Cave Painting,” have offered a wealth of concepts and approaches to the semiologic effects of these pigmented microbiological agents.

Alicia Chang, “Scientists detail impact of ‘Big One’ quake in California,” USA Today, May 22, 2008 →.

Surrealist intellectual and historian of science and of ritual Roger Callois ventured an exemplary foray into such a field of petro-poetics in his unsurpassable volume The Language of Stones, accompanied by his own extensive collection of stone and rock cross sections. In preparation for the forthcoming sequel to Medium Earth, The Otolith Group will visit the Callois stone library.

Kodwo Eshun details the earthquake sensitive as a self-formed epistemic barometer at the thresholds of geo-acoustic awareness. See Eshun, “Medium Earth: Seismic Sensitivity as Planetary Prediction,” in The Whole Earth: California and the Disappearance of the Outside (Berlin: HKW, 2013).

Fernand Braudel, On History (Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1982), 65–75.

Here we attempt a reading of landforms and their displaced circulation via Elizabeth A. Povinelli’s conception of the “embagination of space by the circulation of things,” as developed in her text “Routes/Worlds,” e-flux journal 27 (Sept. 2011) →.

Achille Mbembe, On the Postcolony (Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 2001).

René Descartes, Le Monde (1633).

Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibniz, “The Many Changes in our globe after its initial creation,” chap. V in Protogaea, trans. and ed. Claudine Cohen and Andre Wakefield (Chicago: Chicago Univ. Press, 2008).

Pliny the Elder, The Natural History of Metals, Book XXXIII, chap. 1 (77–79 AD).

This site-specific mural was commissioned for A Special Arrow Was Shot In The Neck … (Curator’s Series #7), June 13–August 2, 2014. Curated by Landings (Natasha Ginwala and Vivian Ziherl) at the David Roberts Art Foundation, London.

In his landmark publication Time and The Other: How Anthropology Makes Its Object (New York: Columbia Univ. Press, 2002), Johannes Fabian critiqued the ethnographic past in which the coevalness of the field was transmuted to a past tense in a process of othering through the written account.

Pliny the Elder, ibid.

This essay was commissioned in conjunction with the exhibition and research project “Allegory of the Cave Painting,” curated by Mihnea Mircan, Extra City Kunsthal (Antwerp), September 19–December 17, 2014. It has additionally been prepared towards the forthcoming edition Landings: Witness Reports featuring Elizabeth A. Povinelli with the Karrabing Indigenous Corporation and other guests, presented in collaboration with Discipline Magazine, the Institute of Modern Art (Brisbane) and Gertrude Contemporary (Melbourne), December 2014. The authors would like to express their deep thanks to Mihnea Mircan, Elizabeth A. Povinelli, Kodwo Eshun, Anjalika Sagar, Anselm Franke, Prabhakar Pachpute, Rachel O’Reilly, Denise Ferreira da Silva, Filipa César, Angela Anderson, and Angela Melitopoulos for their sustained dialogue during the preparation of this essay.