Nationalism is not just in Hungary’s backyard, it is in every corner of the house from the basement to the roof. It gets inside with the air and has completely soaked through the orifices of the building: the front door, the windows, the chimney, the front yard. For this reason, Kriszta Nagy, a Hungarian painter who exhibited her work last spring at Godot Gallery in Budapest, feels she has no other option than to paint the leader of Hungary on bedsheets and tablecloths. She explains the reason for her fifty-seven Pop portraits of Viktor Orbán: “The prime minister sleeps in our bed. He is on our tablecloth.”1

Nationhood is constantly and vigorously flagged: national symbols are everywhere. Even protesters and activists opposing the regime’s politics feel a pressing need to take back the national symbols—currently appropriated for official use—because those not regarded as Hungarian enough are excluded from the notion of the nation. Among other tools used for building nationhood, the reproduction of the nation’s visual culture is constantly recruited. Hungary’s authoritarian regime, with its centralized, highly controlled system, is replicated in the administration of the arts. It is hard to grasp this complex and overwhelming phenomenon.

Flagging Nationhood in Everything Sacred and Profane

After reconfiguring electoral rules in favor of reelection, and pursuing an aggressive, populist campaign amidst apathy, the right-wing regime won the Hungarian election on April 6, 2014. Now, it is finalizing what it began building in the previous mandate. According to the party’s program, this can be condensed to just a single sentence: “We continue.” Concerning the arts, the goal is to achieve a traditional, conservative, Christian culture, conveying a historically rooted image of a strong and proud Hungary. Fidesz, the ruling party in Hungary, used this image on its billboards for the European Parliament elections. The message “We are sending word to Brussels: Hungarians demand respect” stood beside the portrait of the prime minister—the same portrait that is replicated fifty-seven times in Kriszta Nagy’s paintings. Victor Orbán regards the EU as a colonizing power. “Bravely” talking back to the colonizer is presented as the main task of the charismatic leader of a nation that is the heart of Europe. The idea is to project an image of a tough, resistant nation-state within the EU, using EU money, with the attitude of the heroic outlaw who robs from the rich and gives to the poor. In reality, the meaning is slightly, but crucially, altered from the fairytale version: “To rob from the external rich and give to the internal rich.”

Funded by European money, the newly inaugurated football stadium and the Puskás Ferenc Football Academy are literally in the backyard of the leader’s residence in his hometown of Felcsút.2 They are emblems of the current cultural politics, which prioritizes sports, especially football, at the expense of the arts and education. “Politicians can, when waving the national flag, advocate sporting policies, so that the flag-waving of sport itself becomes another flag to be waved”—thus states Michael Billig, who coined the term “banal nationalism” to indicate that nationalism is not removed from everyday life, but is constantly flagged through banal habits.3 According to Billig, this is how the phenomenon is omnipresent in Western, affluent countries. He points to sports and its relation to masculinity as some of the habits that enable the established nations of the West to be reproduced.

Nationalism is flagged literally on public buildings as well. At the Hungarian parliament, the Székely (Szekler) flag is now commonly hoisted next to the Hungarian one, while the EU flag is missing, clearly demonstrating that neonationalism has reached the mainstream. The message is that minority communities of ethnic Hungarians living abroad (for example, the Székelys in Transylvania, Romania, which once belonged to Hungary) are now being reclaimed by the Hungarian government—a quite disturbing and destabilizing message in the time of the Ukrainian-Russian crisis.

Another guiding principle of the current administration is Christianity. Football stadiums are to be consecrated, as was the case with the Felcsút soccer stadium last Easter. However, this revival of religious sentiment in a generally secular postcommunist country inevitably comes together with a variety of prospering new religions, among them shamanism and the cult of pagan Hungarian mythology. All of these religions can now apparently coexist without any conflict.

The revival of the symbolic imagination of Hungary as Regnum Marianum has been combined with the cult of the Turul, the mythological bird of ancient Hungary (and later the symbol of Greater Hungary in the revisionist ideology of the interwar period, following the Trianon Peace Treaty in 1921). Thus, the four-meter-high statue of the Virgin Mary, erected on the Cortina Wall of the Buda castle, facing Pest on the other side of the Danube, is also in peaceful coexistence with the many Turul statues around the capital and throughout the Hungarian countryside.4

A statue of an eagle swooping down on the angel Gabriel—personifications of Germany and Hungary, respectively—has now been erected in Freedom Square in Budapest. It sets the regime’s historical genealogy and holds utmost importance for its symbolic politics. The statue, which is supposed to commemorate the Nazi occupation of Hungary, stirred a heated debate about monuments dedicated to historical events, which are usually erected based on wide social consensus. However, the opposite was true in the case of this statue: in Hungary, the politics of memory is a “muscle politic.”5 Hence, the prime minister does not mind stating that “the artwork is precise and immaculate from an ethical point of view, and also from the point of view of its form as [well as] the historical content it articulates,” in an open reply to an art historian who wrote him a letter (the exact contents of which is unknown), presumably emphasizing the highly sensitive nature of the controversial monument.

According to the government’s website, the monument pays tribute to “all Hungarian victims, with the erection of the monument commemorating the tragic German occupation and the memorial year to mark the 70th anniversary of the Holocaust.” However, activists as well as historians and social scientists in the Hungarian Academy of Sciences regard it as a falsification of history, because the monument does not differentiate between victims and perpetrators and does not acknowledge the Hungary’s responsibility for its participation in the Holocaust. Near the place that had been designated for the monument, a counter-monument called “Living Memorial” was set up by a small group including members of the grassroots organization Free Artists.6 People put personal objects and stones there and started conversations about historical traumas. Since their defeat in the latest election, leftist and liberal politicians have been criticizing the monument to their own advantage. Moderate politicians regarded the constant protests as hysterical and untimely, while the ruling party completely ignored the debate. In the middle of the night on July 20th, the monument was erected despite the ongoing protest. If anyone among the conservative supporters of the government was to have any doubt or hesitation in supporting the monument’s erection, an ideological guideline is available in the form of the PM’s “private letter.”7

Furthermore, the rhetoric of the ruling party is based on the idea that the socialist period was illegitimate and that the previous government did not accomplish the political transition the country needed. The current administration picks up the political thread from March 18, 1944, the day before Hungary, as they claim, lost its independence with the Nazi occupation of the country. Given Orbán’s view that this independence was not regained until 1989, the socialist period is thus erased from the country’s history.

Museums as Fortresses of the Nation

The new right-wing government realized that museums, as privileged spaces of national self-representation, had to be more closely controlled, since they were perceived as too cosmopolitan and independent. Some institutions dared to argue against bureaucratic decisions, as was the case with Imre Takács. Takács opposed the moving of the Esterházy collection to the Esterházy Palace in Fertőd. After Takács’s resignation, the Museum of Applied Arts fell into a state of interregnum, not an unusual condition in the local art world. One of the Ministry of Culture’s first measures following the spring 2014 election was to delegate the task of the “professional, organizational, and operational renewal” of the Museum of Applied Arts to László Baán, director of the Museum of Fine Arts. At the time, Baán already controlled the three major art museums in Budapest. His promotion was quite extraordinary, especially considering that he has no training in art history. One by one, museums were taken out of the hands of professional directors and were placed under his authority.

The Hungarian National Gallery, located in the Buda Castle, was annexed on August 31, 2012 by the Museum of Fine Arts, a storefront museum that receives lavish financial support at the expense of other museums struggling to survive. A smaller but highly important museum of strategic interest, the Ferenc Hopp Museum of East Asia Arts, also fell prey to Baán. After the reelection of the Fidesz Party, it became clear why this seemingly marginal museum was incorporated. Baán, besides overseeing the ambitious creation of a museum quarter in Városliget Park in Budapest—a plan called the “Liget Budapest Project”8—has also been assigned to develop an Asian art center crucial for opening diplomatic relations with the East.

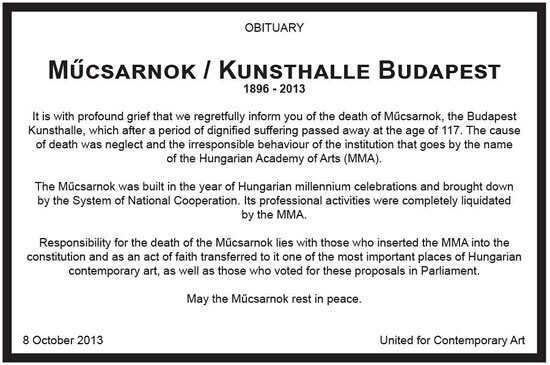

The Műcsarnok (Kunsthalle Budapest) has operated without a professional leader for quite a while after his previous director, Gábor Gulyás—who had been appointed to that post without any competition from other candidates—resigned (only to be promoted afterwards to a higher position), under the umbrella of the Hungarian Art Academy (HAA), a kind of shadow ministry that grew out of a private organization. This ultraconservative institute is gaining full power over cultural issues, controlling the subsidies given to the arts while it favors “national culture within the culture of the nation.” How this program will affect the Műcsarnok, the most important venue for contemporary art in Hungary, is still unclear.

Protest Movements Against the Vehement Flagging

Some cultural activists and other protesters, however, have been disrupting the image of Hungary as a “clean garden, proper house” by boycotting self-congratulation occasions organized by the new official culture. The internationally known philosopher Gáspár M. Tamás accurately stated that contemporary Hungarian culture is not against the ideology of the recent administration, but rather against its acts. Although some artists have merely reflected on the nationalist ideology, the cult of the leader, and the falsification of history, other artists have produced collaborative, critical, and socially engaged work—a kind of activism.9

The artists Szabolcs KissPál and Csaba Nemes, among others, initiated Free Artists in opposition to the empowerment of the HAA. Their first action was an interruption of HAA meetings to demand that art remain autonomous from party politics. When the Műcsarnok was taken over by the HAA, young curators, as well as the respected art critic József Mélyi, initiated regular actions and events outside the museum. These events were entitled “Outer Space” and protested the right-wing invasion of an independent art institution.10

In response to the nontransparent process behind the appointment of a new director at the Ludwig Museum, a few dozen artists and art professionals established the group United for Contemporary Art. In May 2013, the group occupied the Ludwig Museum. The occupiers—artists, art historians, curators, and students—demanded complete transparency in the selection process, autonomy from political power for cultural institutions, as well as a dialogue between museum professionals and ministry officials. Many of the occupiers—including many members of the Free Artist group—slept and ate on the stairs in the museum, besides organizing forums and events there. When director Gábor Gulyás resigned and the HAA took over the Műcsarnok, contemporary art’s fortress in Hungary, Free Artists responded by organizing a kind of group performance: a burial ceremony for the flagship institution.

At the time of the occupation, the new right-wing museum officials held an event at the Vigadó Concert hall on the banks of the Danube, one of the most beautiful art nouveau buildings in Budapest. Artists disrupted the celebration to raise awareness of the financial imbalances in the art scene and the absolute power of the ultraconservative museum regime. This protest was similar to the one that took place at New York’s Guggenheim Museum, where activists sprinkled fake money and leaflets on museum visitors to protest against the inhuman labor conditions at the construction site of the new Guggenheim museum in Abu Dhabi. Although the Budapest protest was called “Raining Money,” the key element here was not money, but rather the defenseless bodies of the protesters lying on the stairs and floor of the building’s entrance.11 All had their mouths stuffed with money, in accordance with the visual and verbal violence that is one of the side effects of the vigorously flagged nationalism that fills everyday life in the heart of Europe.

Kriszta Nagy, I Take on Painting Portraits, exhibition at Godot Gallery, Budapest, May 15–June 14, 2014.

See →.

Michael Billig, Banal Nationalism (London: Sage Publications, 1995), 123.

See Cara Eckholm, “Hungary’s Identity Crisis Fought in Concrete and Bronze,” FailedArchitecture.com, May 14, 2014 →.

For the group’s blog “no MMA!,” which provides news coverage and commentary about the monument controversy in multiple languages, see →.

See (in Hungarian) →.

See →.

See Maja and Reuben Fowkes, “Hungarian Art in the Eye of the Storm,” no MMA!, July 23, 2013 →.

For the website of Outer Space, see →.

For coverage of the action, see the no MMA! blog →.