Over a Lebanese dinner in London, a Dutch friend and fellow artist recently told me about a leak in the Dutch press relating to Martin Bosma, a prominent figure in the Party for Freedom (PVV) in the Netherlands and best known as the speechwriter and ideologue of the notorious Geert Wilders.1 The PVV is a right-wing political party that advocates for the withdrawal of the Netherlands from the EU and is attempting, together with Marine Le Pen’s National Front in France and Nigel Farage’s Independence Party in the UK, to create the first anti-European block in the EU parliament. The leak concerned Bosma’s failed attempt to publish his book Handlangers van de ANC-apartheid (Accomplices of ANC apartheid), in which he tries to make a correlation between the political scene in the Netherlands and that of South Africa. Bosma frames South Africa as a country where the ruling African National Congress (ANC) is plotting an apartheid-esque reverse subjugation of its white minority population. He focuses specifically on Afrikaners and their not so distant Dutch past. Things become even stranger when he compares this fabricated South African setting to his homeland, where he claims conservative, right-wing supporters are being legislated into oblivion by an ethnically and culturally diverse Dutch left. Such an analogy reveals the far right’s reinjection of naturalizing rhetoric into the political sphere. Bosma attempts to capitalize on the fear of the unknown, here represented by South Africa. He refers to Afrikaners as guinea pigs and to the rest of the masses, which he assumes to be supporters of the ANC, as lions.

Meanwhile, in the recent South African elections, a newly formed opposition party to the ANC, the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), won 6.35 percent of the vote, making it the second-largest opposition party as well as South Africa’s youngest party. At their swearing-in ceremony in Parliament on May 19, the twenty-five seat-holding members of the EFF were dressed in miner’s overalls and maid’s uniforms (in red, head to toe), representative of the uniforms that the majority of South African workers wear each day. This red also represents the blood of the fallen heroes and heroines of the liberation struggle.

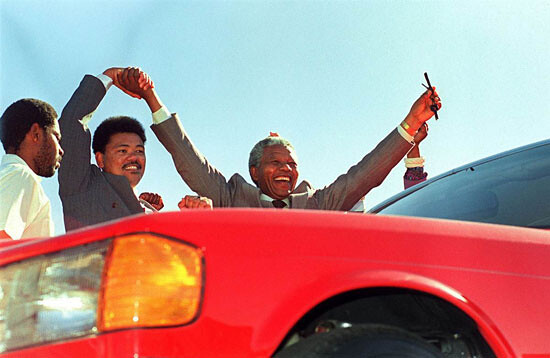

In 1990, Nelson Mandela was presented with a red S-Class by the workers of a Mercedes-Benz factory in East London, South Africa. The color, “revolutionary red” was chosen by the workers. Upon accepting the car, Mandela said that its color would remind him of the blood spilled by South Africans in the struggle to end apartheid. Simon Gush and James Carins’s video work Red2 chronicles the story of the infamous red Benz, delving into a South Africa where labor relations were stalling across the country as oppressive apartheid legislation slowly began to unravel. The Mercedes factory faced fifty-two strikes in 1989, with repeated threats of closure by its parent company, Daimler Chrysler. The new labor laws that would come into effect in 1995 were only just being conceived, and the country’s economic future had not yet been pinned to international capital markets. Red recounts the riveting events of a company and labor force trying to achieve an equilibrium of power relations where no such structures existed. Workers demanded better pay, better working conditions, and equal treatment irrespective of race.

Similarly, the main goal of the EFF is to redress inequality in South Africa by taking up the issues of “mine workers, farm workers, private security guards, domestic workers, construction workers, and unreasonably paid undergraduates.” The party was founded in August 2013 by Julius Malema, the axed president of the ANC Youth League. The far-left EFF sees its political ideals departing from the ANC’s collusion with international capital. One of its most important card-carrying members, Dali Mpofu, who is another defector from the ANC, links his own departure to the ANC’s Freedom Charter of 1955.3 In that year, the ANC sent fifty thousand volunteers into townships and the countryside to collect and document the demands for freedom made by the people. On June 26, 1955, the charter was read aloud to more than three thousand people at the Congress of the People in Kliptown. The charter, which called for democracy, human rights, land reform, labor rights, and the nationalization of key industries, was denounced as treasonous by the South African government at the time.

Mpofu felt that at the latest ANC congress held in 2013, the party departed, for the first time since its adoption of the Freedom Charter, from what the people had demanded. Yet this transition had arguably begun far earlier; since the advent of South Africa’s democratic era in 1994, neoliberal tendencies spearheaded by the Ministry of Finance have caused land reform, labor rights, and nationalization to decelerate significantly.

In South Africa, where poverty and inequality are at levels unimaginable for a developed country—with a 24 percent unemployment rate that has remained relatively stable for the last twenty years, and the world’s highest GINI coefficient (0.63–0.7)—these matters are serious indeed.4 In the case of negotiations between the Mercedes-Benz plant and its workers, a far- reaching agreement meant that workers received pay increases, their community spaces were upgraded, and working conditions in the plant improved. The integrated solutions at the plant were so successful that it became one of Mercedes-Benz’ best-run plants in the world, and it stayed strike-free for twenty-two years. This early experimentation and hard-fought success story did not get widely emulated in South Africa’s democratic era. The recoupling of the nation’s economy to neoliberal markets made negotiations such as these more rare. They simply took too much effort in a world economy in which it is more expedient to set up a new factory in another country than to work with what is at hand.

The EFF calls for the nationalization of mineral rights, land restitution without compensation, and union raises that are on par with the real costs of living. Some of its propositions echo the freedom demands of sixty years ago during apartheid rule. Yet the largely white-owned media in South Africa paints a picture of the EFF as a party of power-crazed lunatics who appear in Parliament, clad in red, as court-jesters for the entertainment of the rest of the population who do not subscribe to their ideology or economic ideas. The media in South Africa is largely owned by a handful of media firms that are backed in part by industry shareholders. As such, the media’s output is imbued with neoliberal rhetoric. A few of these media houses are international players, owning shares in media outlets around the world. They thus hold considerable sway in distributing these views internationally.

During this year’s national elections, Red was part of Simon Gush’s solo exhibition—which was itself called “Red”—held at the Goethe Institute Johannesburg. The exhibition dealt with events in the year 1990, a moment in South Africa’s history when the country’s spirits were on an upward swing. Nelson Mandela’s release from prison had just been announced, and an entire country was waking up from a state of repression.

For Gush, the project centers on the possibility of labor escaping a purely production-driven imperative and developing a more meaningful purpose, one that can help build identity and contribute to personal growth. The red Mercedes, built through cooperative resolve—workers devoted an hour of unpaid work each day to assembling it—became a symbol in which everyone in the country saw himself or herself. (For me, it is emblematic of the energy required to move South Africa out of an elite and racist system and into one of racial equality and democracy.) Soon after the red Mercedes was made, wage negotiations at the factory failed, leading to a wildcat strike and a factory occupation. Five hundred employees were dismissed for these actions, yet these tumultuous events led to this same factory becoming one of the most efficient of its kind in the world. It has won numerous awards for excellence in automotive manufacturing.

A work that Gush made in collaboration with fashion designer and artist Mokotjo Mohulo touches on the factory occupation. The work presents fictional workers’ outfits made out of materials used in the Mercedes-Benz plant. It points to the possibility of converting work into artistic output. During the factory occupation, workers used automotive materials from the factory to create makeshift beds and blankets. Gush and Mohulo’s creation proposes a radical departure from what a worker is perceived to be. It proposes a future where work, artistic output, and emancipation are all intertwined—where there is a different relationship between work and nonwork, where the output of work has no definable goal other than a self-fulfilling relationship between an individual and his or her work. Here, the idea of work as a possible artistic output puts into question the notion of the “red uniform” as imagined by the EFF. While the EFF’s parliamentary gesture shows clear allegiance to the worker, it remains constrained within the very model it is trying to criticize, one where workers are just another cog in the wheel of the neoliberal economy. Yet this symbolic gesture is in the short term a perfect rallying cry for mobilizing a South African populace which has had little symbolic power to cling to since the departure of Mandela from the political scene in 1999.

This brings us back to the decoupling of the freedom demands of the people and the new neoliberal route that the ANC embarked upon in order not to frighten foreign investment, a vital necessity after the apartheid government had almost bankrupted the country by pilfering the treasury for years.5 In desperate need of international capital investment and loans from the IMF and World Bank, the new government implemented many neoliberal reforms, which it hoped would help break the stigma that had surrounded the country during the economic sanctions of the 1980s. It worked. International investment flooded into a country that had seen its connection to international markets largely vanish during the sanctions era. While this influx led to stellar economic results in the first decade of democracy, since then, South Africa’s strong labor rights have been under consistent attack by market forces.

A year before being officially elected South Africa’s first democratic president in 1994, Mandela opened the Cultural Development Congress by stating, “That which we collectively contribute to our national cultural identity will live forever, beyond us.”6 He argued for the importance of art and culture as tools for overcoming the apartheid weapons of minority rule, torture, detention, carnage, and massacre. Mandela envisioned a cultural sphere emerging in South Africa, not as a creative market of speculation, but one where social bonds would be reconstituted—perhaps a place where art could be seen as real work. What followed in his term as president was consistent financial support from the government for arts and culture, at a time when the national treasury was strapped for cash. Even under direct criticism, Mandela consistently defended the importance of the arts for South Africa’s future. Since the Mandela era ended, South Africa’s arts and culture budget has been consistently cut year after year.

In 2012, however, the Department of Arts and Culture took a considerable new policy direction. It invested €1.5m (R17m at the time) to renovate a space at the Venice Biennale and lease it for twenty years.7 With South African artists becoming more prominent in the international market, and with homegrown art fairs emerging, the speculative art market has certainly made an impression on the Department of Arts and Culture. After a fraught first exhibition at the Venice Biennale in 2011, in which financial irregularities were rampant,8 a more transparent process was developed for the 2013 edition. The South African art community has called for the Venice Biennale space to undergo further scrutiny to ensure that it becomes a more representative space for artistic output emerging from the country. A call for the 2014 edition has yet to be made public.

Parties like the EFF have helped to revisit the core neoliberal values that the South African economy was based upon twenty years ago, and bring this necessity into the media spotlight. In Jacob Zuma’s inauguration speech on May 24, he called for the “radical socio-economic transformation of policies and programmes” during his upcoming term, a rather under-the-radar comment, but likely the first time that any mention of radical economic transformation has been made by a government official since 1994.9 While the EFF and its demands are seen as a joke by the South African media, the ANC is actually listening, lest it find its majority of 62 percent slipping further in the next local elections two years from now.

And yet, 9,202 kilometers away in the Netherlands, a right-wing party ideologue has found it within himself to write a manuscript about a neo-apartheid state focused on subjugating its white minority population. “The Afrikaners, that’s us,” wrote Martin Bosma. “The Afrikaners of today are the Dutch of fifty to a hundred years from now.”

Bosma claims that a progressive and culturally diverse society will be the downfall of the Dutch. South Africa, of course, could not be more different from the imaginary figure that Bosma has tried to make of it.

South Africa’s conservative neoliberal policies have frozen it into a mire of inequality. Everyday people are getting poorer and more desperate, and the ruling elite find it unnecessary to invest in the cultural sphere in order to aid in social cohesion. Such funding is desperately needed after decades of brutal apartheid repression, yet it is hard to come by because there is no easily quantifiable connection between social wellbeing and economic development. The story of the “revolutionary red” Mercedes-Benz seems to have been forgotten. Or perhaps the subsequent economic success of the factory was too hard-won to be of interest in a world of fluid capital, where, for example, South Africa’s currency has fluctuated wildly over the last two years.10 The white minority, which is less than 10 percent of the population, is still in control of 90 percent of the stock exchange.11 Indeed, it is the other 10 percent—or to be more precise, the 6.35 percent who cast their vote for the EFF—who can no longer carry on with the lies of a neoliberal agenda that promises and delivers growth, but into all the wrong pockets. This minority, for the moment, is not white. It is not made up of Afrikaners or British expats. It is largely made up of the disenfranchised black people of South Africa, who have been losing ground year after year in the international post-apartheid success story that is South Africa. Like its apartheid predecessor, the wealth that has made this success story possible is rapidly being taken away from the people who have helped produce it.

For a news article about the leak, see (in Dutch) Jan Hoedeman, “PVV’er Martin Bosma voorziet ondergang blank Nederland,” de Volkskrant, May 21, 2014 →.

See →.

Dali Mpofu, “Why I Left The ANC To Join EFF,” Radical Voice vol. 9, issue 9 (Nov. 13–20, 2013) →.

Richard Poplak, “HANNIBAL ELECTOR: Exit Stage Right—the final days of Trevor Manuel,” Daily Maverick, April 21, 2014 →.

Nelson Mandela, “Statement of the President of the African National Congress, Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela, on the occasion of the opening of the Cultural Development Congress at the Civic Theatre,” April 25, 1993 →.

M. Blackman, “Department to pay a possible R29 million for Venice 2013—Curators given 19 days to make proposals,” Art Throb, January 22, 2013.

Charl Blignaut, “SA’s Venice art scandal grows,” City Press, August 1, 2013 →.

“Zuma’s inauguration speech,” IOL News, May 24, 2014 →.

Maarten Mittner, “Rand could face another volatile year,” Business Day Live, December 27, 2013 →.

Tiisetso Motsoeneng, “Black South Africans come up short in share ownership,” Reuters, Dec. 6, 2012 →.

Special thanks to Simon Gush, Jonas Staal, and Brian Kuan Wood.