NSK and its groups never spoke the political language of the day. This, however, does not mean that we did not respond to aggressive nationalist politics. We did not want to fall victim to the phantoms of the past, being well-aware that the more that totalitarian and nationalistic symbols were pushed under the rug and prohibited, the more they assumed diabolical power. This was also one of the reasons why, in our paintings, Irwin juxtaposed the motifs and styles of modernism and contemporary art with totalitarian art styles and national motifs. We were aware that there is a wide space between regressive nationalism and “esperanto” internationalism, and that mere criticism of nationalism without reflection would not make it disappear. Interestingly, despite our iconography, we were not of much interest to ultranationalists in the long run. In fact, they were mostly quite disappointed and perplexed when they looked more closely at us. They attended the events of NSK and its groups because our iconography was apparently appealing to them, but its content did not meet their expectations and they did not know what to make of it. Because our artistic procedures and works did not contain a safe ironical distance that would be recognizable at first glance, we were subject, from the very start of our activity, to numerous accusations of being nationalists and flirting with totalitarian ideologies. In time, such reactions slowly died down and became very rare.

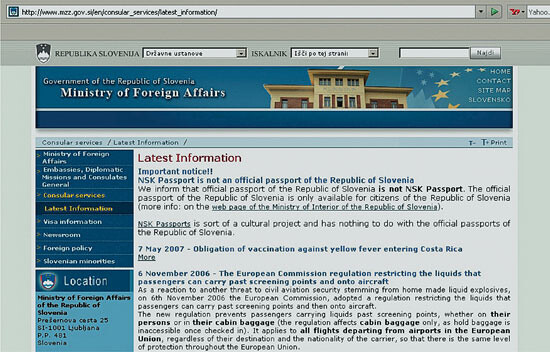

The NSK art collective was formed in 1984 in Yugoslavia by three groups active in the fields of visual art, music, and theater: Irwin, Laibach, and the Scipion Nasice Sisters Theatre.1 Later, other groups joined in, among them the design group New Collectivism and the Department of Pure and Applied Philosophy. Crucial for NSK’s operations and its development were collaboration, a free flow of ideas among individual members and groups, and the joint planning of artistic actions. In 1992, the NSK transformed into the NSK State in Time as a response to the radical political changes that were taking place in Yugoslavia and Eastern Europe at the beginning of the 1990s. In addition to organizing projects such as temporary embassies and consulates, the NSK State in Time also started to issue its own passports in 1993. Currently, there are approximately 14,000 NSK passport holders around the world.

The NSK State in Time came into being after the disintegration of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, which was marked by wars in the former Yugoslav republics of Slovenia, Croatia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina, as a transnational reaction to the aggressive nationalisms spreading throughout the territory of ex-Yugoslavia.

As early as the beginning of the 1980s, Laibach and NSK triggered debates about nationalism by using German names, which clearly caused discomfort on the part of the authorities. Why the use of the German language for “new Slovenian art”? Why did the Laibach group take on the old German name for Ljubljana, today’s capital of the Republic of Slovenia? Laibach, in particular, sparked lots of hostile reactions from the authorities throughout Yugoslavia. For some time in Slovenia, there was even a ban on the use of the name Laibach, carrying a mandatory fine equivalent to about 500 German marks. Here, I must explain that German culture had exerted a huge influence on Slovenian culture for almost one thousand years. But during World War II, Slovenia, like the rest of Yugoslavia, was under German occupation. Slovenians were subjected to aggressive Germanization and even prohibited from using their language in public. Large numbers of people were killed as hostages or perished in concentration camps. The role that this ultranationalistic and racist project reserved for Slavic nations was, at best, slave work in East European fields and factories. Thus, after the traumatic experience of WWII, the German language was understood in Yugoslavia as the language of the occupier, yet at the same time also as the language of high culture and philosophy, the language of Goethe, Hegel, Mann, and others. The use of German in the name “Neue Slowenische Kunst” indicated this double nature of our experience with the German cultural and national space.

Through our artistic procedures, we also wanted to provoke debate about national conflicts that were swept under the rug after WWII but erupted violently following the fall of the Berlin Wall, particularly in the territory of the former Yugoslavia. In socialist Yugoslavia, public discussions and reflections on national issues were taboo. Long-running national conflicts, from the Balkan Wars in the beginning of the twentieth century through World Wars I and II, were artificially frozen after WWII and then artificially provoked in the beginning of the 1990s by essentially the same politicians who played important roles in socialist Yugoslavia.

In the maelstrom of war in Croatia, when Dubrovnik was bombarded from the territory of the then Yugoslav Republic of Montenegro, Irwin was invited to participate in an international contemporary art biennial in Cetinje, Montenegro. We declined the invitation, explaining to the organizer that we did not want to be a factor of normalization in a situation in which the country hosting the biennial was conducting aggressive military operations. In this case, contemporary art was used as an instrument of normalization in a national conflict that escalated into war!

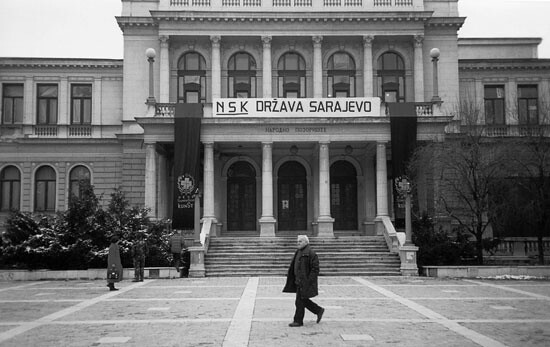

The beginning of the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina closely coincided with the opening of our first NSK Embassy in Moscow in May 1992 and the founding of the NSK State in Time upon our return to Slovenia. In 1995, at the invitation of artists from Sarajevo, NSK travelled twice to the besieged city, where Irwin, in collaboration with the Ljubljana Museum of Modern Art and Sarajevo artist Jadran Adamović, organized an international collection of contemporary art (with works donated by European and American artists), which is now part of the collection of Ars Aevi, a Sarajevo museum of contemporary art in the making. When this collection was displayed in Ljubljana in 1996, we also organized, together with the Ljubljana Museum of Modern Art, an international symposium of artists and theoreticians titled “Living with Genocide,” which dealt with the question of why the international art community could react and critically reflect the war in Vietnam, but failed to do so in the case of the Bosnian war.

Also, we have always been aware that contemporary art (irrespective of its declarative commitment to transnationalism) and nationalism are not necessarily mutually exclusive. There is no need to look very far to see this. The Venice Biennale is mostly still organized according to national principles, i.e., by national pavilions. When Irwin was invited to represent Slovenia at the 1993 Venice Biennale, we did not like the idea of us, as artists, representing a nation, i.e., the Slovenian state, so we set the condition that we would participate in the Biennale only if the NSK State was hosted by the Slovenian pavilion, i.e., only if Irwin was presented in the pavilion of the NSK State in Time. The Ljubljana Museum of Modern Art, as the organizer of this event, accepted our proposal and so we presented ourselves at the 1993 Venice Biennale as artists from the NSK State in Time.

At the turn of the century, the NSK State acquired unforeseeable dimensions. In 2001, Haris Hararis from Athens launched the unofficial NSK website NSKSTATE.COM, which became the central meeting point for NSK citizens. Around this time, it became clear that the citizens had begun to self-organize, both online and in the real world. They used the iconographies of the NSK State in Time and NSK groups as a basis for their own artifacts, actions, and responses. To mention only some of them: in the United States, filmmaker Christian Matzke opened, on his own initiative, an NSK library. In Reykjavik, NSK citizens organized the NSK Guard of Iceland and opened their own NSK embassy. We decided to support such initiatives, not to restrict them. In 2007, Irwin and NSKSTATE.COM began collecting these artifacts and named this phenomenon NSK Folk Art. These works, made in various styles and contexts, are often unpredictable responses to NSK’s work and symbolism.

Today, the citizenry of the NSK State includes people from seventy countries around the world. They organize themselves via the internet and NSK “rendezvous,” as they named their meetings in 2010. The First NSK Citizens’ Congress, which took place in Berlin in 2010, showed that the citizens were willing to take the NSK State in their own hands. This year, citizen-artists organized the First NSK Folk Art Biennial in Spinerei, in Leipzig, Germany. The exhibition, which presented fifty artists from twenty-two countries, was seen by around twenty thousand visitors.

Another point to be made about the NSK State in Time is that a large number of NSK citizens come from Africa. Since 2006, about three thousand people from Nigeria have applied for and received NSK passports. This phenomenon is obviously linked to the fact that the huge majority of Nigerians cannot leave their country. Here, this contemporary art project bumped into reality. Of course, we explained to them that the NSK State is a state without a territory and that they cannot legally travel across borders with its passport because it is not an internationally recognized document. We also warned them that any attempt to cross international borders with this passport might have serious consequences, but at the same time, we did not deny them NSK citizenship.

Such a massive number of applications for NSK passports from Africa prompted us to start organizing interviews with NSK citizens from first, second, and third world countries. Among the reasons given for applying for the NSK passport, some of the interviewees stated that NSK citizenship enables them to belong to more than just one state and nation, that with the NSK passport they can at least partly overcome this limitation.

I see the NSK State in Time as an experiment that is opening up new spaces of social organization beyond the borders of nation states. The beauty of this project lies in the fact that its outcomes cannot be predicted. The NSK State in Time is an artifact which has taken on a life of its own, independent of its original creators.

Since the Neue Slowenische Kunst (NSK) art movement has long ceased to appear in the media as a collective, after consulting with my colleagues I decided to present my personal views on the issue of ultranationalism for this edition of e-flux journal through the prism of the experience of NSK and NSK State in Time, of which I am a cofounder.

Category

Subject

Ljubljana, June 2014