Ultranationalism and the “Deep State”

There doesn’t seem to be a worse moment than the present to defend the project of stateless internationalism. The recent European elections of May 2014 showed the growing influence of ultranationalist parties on the political establishment; in terms of representation in the European Parliament, ultranationalist parties became the largest parties in France (National Front), Denmark (Danish People’s Party), and the United Kingdom (United Kingdom Independence Party), while gaining substantial ground in Austria (Freedom Party of Austria) and Sweden (Swedish Democrats), and remaining relatively stable in the Netherlands (Freedom Party). They suffered heavy losses in Belgium (Flemish Interest), but this was due to the success of a slightly more moderate and competing nationalist party (New Flemish Alliance).1 The next step for these ultranationalist parties has been to seek alliances and prepare to deliver the final blow to the supra-nationalist managerial project of the European Union. Their challenge is to convince EU parliamentarians from seven or more different countries to unite in order to, as Le Pen has said, make the EU “disappear and be replaced by a Europe of nations that are free and sovereign.”2

The leaders of the ultranationalist parties seem to be in permanent competition to radicalize the discourse concerning immigration and failing economies, with the hope that their arguments will help reclaim national sovereignty from the EU. These arguments range from Marine Le Pen in France claiming that the Muslim community is the new anti-Semitic danger of the twenty-first century, to the Danish People’s Party declaring that Denmark should be kept “Danish for the Danish,” culturally as well as economically. Their main obstacle does not seem to be a strong international progressive counterforce, but rather their own incapacity to deal with each other’s extremisms, leading to two prominent, competing right-wing blocks. One block organized itself into a coalition called Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy (which includes the UK Independence Party, the Swedish Democrats, and, to the surprise of many, the Italian comedian Beppe Grillo’s Five Star Movement), while the other block organized itself into the European Alliance for Freedom (which includes the National Front, the Freedom Party, and Lega Nord). The parties from both blocks attempted to collaborate, as this is the only way they could gain enough subsidies from the EU, but for now were unable to reach an agreement due to opposition against the anti-Semitic rhetoric of the National Front. This means that for now, the strength of the ultranationalists is limited to the UK Independence Party’s group.

It is important to observe that at the very time that we are confronted with the rise of ultranationalism, we also face the growing influence of a set of structures which have emerged alongside and parallel to ultranationalist movements. Whereas ultranationalism uses fundamental democratic rights to spread a thoroughly antidemocratic rhetoric steeped in racism, anti-Semitism, discrimination, and so on, these other structures develop out of democratic decision-making but turn against the fundamentals of democratic politics, such as accountability, legality, and transparency. The development of these structures follows naturally from neoliberal ideology, which incessantly argues for the abolition of the state altogether (while depending on the state to be “bailed out”). These structures are what former diplomat and Vietnam-War-critic-turned-professor Peter Dale Scott has called the “Deep State,” a term he borrowed from Turkish analysts. The Deep State becomes apparent through, for example, assignments “handed off by an established agency to organized groups outside the law.”3 In the context of the War on Terror, writer and journalist Nafeez Mosaddeq Ahmed describes these practices that outsource decision-making to entities that are not accountable to the public as

a novel but under-theorized conception of the modern liberal state as a complex dialectical structure composed of a public democratic face which could however be routinely subverted by an unaccountable security structure.4

In simpler terms, our age of mass surveillance by secret agencies in “democratic” countries, assisted by the massive amounts of data handed over by corporate entities such as internet service providers and social media companies to organizations such as the National Security Agency (NSA), has led to the rise of new political structures that fall outside the democratic control of people, and often even of politicians themselves. The rise of these political structures may at first glance seem opposed to the rise of ultranationalism, though in fact, they are mutually supportive.

For example, in the Netherlands, Geert Wilders’s Freedom Party—which, together with Le Pen’s National Front, has been one of the strongest voices in the anti-EU and anti-Islam movement in Europe—was a product of the post-9/11 era. Wilders’s argument for closing borders and forcing the return of Dutch-born Muslims to their “country of origin” comes from his belief that Muslims in Europe have become a “fifth column” (a term used to describe a clandestine military unit). Wilders claims that these Muslim “sleeper cells” are seemingly moderate, but in fact can strike against democracy at any moment.5 It is no coincidence that Wilders, during one of his many fundraising visits to the US, took the opportunity to visit its military prison in Guantánamo Bay. Immediately afterwards, he stated:

I ask the government to build a Dutch detention center for potential terrorists, modeled after Guantánamo Bay, in order to imprison the potential terrorists known to the AIVD [Dutch Secret Service] as a precaution … I would gladly lay the first stone.6

Just like his colleagues from the anti-EU block, Wilders propounds a phantasmatic, conservative utopia of the “homeland” as it once was and should become once more. Needless to say, these presumed origins of the Netherlands that are allegedly being lost never existed in the first place. Wilders’s homeland that would close its borders, build its own Guantánamo Bay, ban the Quran, and prohibit the wearing of headscarves in public buildings may seem to limit itself to the territorial space where the “authentic” Dutch citizen supposedly dwells.7 But it serves that other homeland just as well: political substructures that consist of the homeland securities of this world, which are increasingly gaining leverage over their own governments.

Recently, the European organization Statewatch published reports exposing the fact that the EU has invested large amounts of tax money into corporate research for the development of unmanned aerial vehicles, otherwise known as “drones”:

€300 million of taxpayers’ money [was invested] in projects centered on or prominently featuring drone technology … [D]rones are being adapted for security purposes through research and development projects, all of which are dominated by European (and Israeli) defense multinationals seeking further diversification into “civil” markets.8

This investment, which the EU legitimizes as “research” (even though this is an obvious case of a supra-national structure subsidizing the security industry), encompasses all aspects of drone manufacturing:

The European Commission has long subsidized research, development and international cooperation among drone manufacturers. The European Defense Agency is sponsoring pan-European research and development for both military and civilian drones. The European Space Agency is funding and undertaking research into the satellites and communications infrastructure used to fly drones. Frontex, the EU’s border agency, is keen to deploy surveillance drones along and beyond the EU’s borders to hunt for migrants and refugees.9

This is an example of the unaccountable structures of the EU merging perfectly with the interests of private lobbies—in this case, to produce equipment for the corporate-mercenary armies of the EU, of which Frontex has become the most notorious.10 This subsidizing of drones is of a piece with other well-known operations of the Deep State: extraordinary rendition flights, which are carried out by “civilian” corporations; so-called “black sites,” which are legal under the policies of friendly nations, even though such policies would be considered unconstitutional in the “homeland”; and the infamous black budgets, which remain outside parliamentary control and which help to sustain the mass criminalization of civilians worldwide.

Most importantly, there is a direct relationship between ultranationalism and the EU’s unaccountable investments into drone technology. For citizens to outsource their agency to the structures of the Deep State, they need to have the will to do so; the fears stoked by ultranationalism create this will. These fears fuel the global extralegal structures that we are confronted with nowadays, and which undermine the celebrated sovereignty of the very states that ultranationalism swears to protect. These states become mere proxies for a war that we only know as “blank spots on the map.”11 Among all the unaccountable aspects of the EU project, ultranationalism proposes that the worst form of unaccountability should become the norm.

During the European elections, some political parties and commentators attempted to combat ultranationalism by making the contradictory claim that far-right parties only wanted to enter the European Parliament in order to stop it from “inside,” so as to wrest back state sovereignty from the moloch of Brussels. But this strategy is nothing but an ideological cover-up for the fact that the ultimate consequence of ultranationalism is the annihilation of parliamentary representation altogether.

Maybe the best illustration of this comes from Wilders himself. Prior to the EU elections, opinion polls promised him and his party a large victory. Instead, his support among Dutch voters shrank—his party lost one of its four seats in the EU parliament. The explanation? His constituency refused to vote in EU elections: 65 percent of his previous voters stayed home and did not vote at all. Wilders won in the polls, but there was no one to materialize his victory. In other words: his constituency had already left the parliament, before he was able to abandon it for them.

Stateless Internationalism

The ultimate outcome of ultranationalism is the disappearance of the state altogether, and its replacement by power structures that do not recognize any form of democratic control by the very people these structures affect. Nor do these structures restrict themselves to what used to be known as national borders. This reality of globalism after the annihilation of the nation-state forms a dark and perverted version of that other dream of decentralized powers that reaches beyond the nation-state: the progressive project of stateless internationalism. The premise of stateless internationalism was echoed in the recent victories of “regular” political parties such as Podemos in Spain, which was initiated by the Indignados movement as a form of parallel political representation: a parliamentary support for street politics, bringing to mind the autonomous workers councils that worked in alliance with the Allende government before his toppling by the military.12 But there are also stateless entities that have continued demanding—in contrast to the ultranationalists who have abandoned parliament—the creation of new political structures altogether.

I will introduce here a number of examples of the infrastructures proposed by groups advocating for different practices of stateless internationalism. These examples are gathered from my work as founder of the New World Summit—an artistic and political organization that develops parliaments for stateless and blacklisted organizations—and as cofounder (with BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht) of the New World Academy, where stateless political groups have developed collaborative projects with artists and students, exploring the role of art in political struggles for representation. The aim of the New World Academy is to investigate artistic practice in relation to the stateless state, with the concept of “state” referring as much to a condition as to an administrative structure.

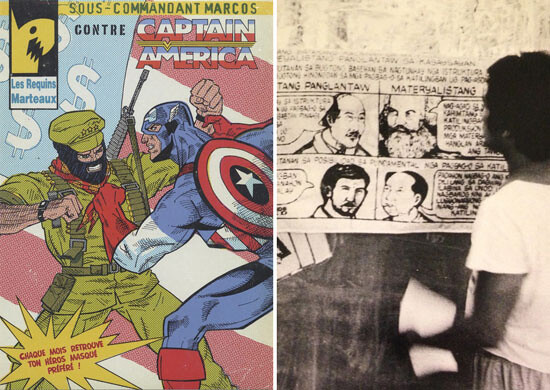

Before Subcomandante Marcos—twenty-year representative of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) in Chiapas, Mexico—stepped down on the day after the European elections, he argued that the struggle of so-called “local” and “indigenous” peoples today is the avant-garde of a war against the generic non-spaces that form the global architecture of neoliberal ideology. He refers to this struggle as the “Fourth World War,” which has followed the Third World War (i.e., the Cold War). He describes this Fourth World War as radically decentralized, with the main adversary being the dispersed apparatus of the Deep State, which he considers a product of neoliberal doctrine:

It is not possible for neoliberalism to become the world’s reality without the argument of death served up by institutional and private armies, without the gag served up by prisons, without the blows and assassinations served up by the military and the police. National repression is a necessary premise of the globalization that neoliberalism imposes. The more neoliberalism advances a global system, the more numerous grow the weapons and the ranks of the armies and national police. The numbers of the imprisoned, the disappeared, and the assassinated in different regions also grows.13

In describing indigenous struggles around the world as the avant-garde of the Fourth World War, Marcos adopts an internationalist stance that acknowledges the peoples of this world as equal yet radically differentiated. Internationalism is thus fundamentally different from globalism, as its solidarities do not translate into a demand for a homogeneous structure of governance. Rather, in the face of countless “disappeared” and “assassinated” indigenous people (as Marcos refers to them), the demand is for history as such. For the inherent paradox of attempting to write a history of the victims of Deep State practices is that deep history is a history that is in a permanent state of self-erasure. As such, the Fourth World War is a cultural war: a war in which the stakes are the possibility of differentiated culture.

During the last EU elections, David Fernandez, a left-wing, pro-independence politician from Catalonia, stated that “We are the Zapatistas of the South of Europe,” referring to left-wing Basque, Catalan, and Galician pro-independence movements. According to Jon Andoni Lekue, a representative of the movement Sortu (which, as part of the left-wing Basque coalition Bildu, just won its first seat in the EU parliament), the party is working towards a political concept of the Basque country as a condition that, as such, applies to all peoples of this world who struggle for the right to self-determination.14 One of the founding resolutions of Sortu addresses the Basque situation mainly by stating the party’s support for other independence movements worldwide, ending with the famous Guevarian phrase that “solidarity represents the affection of peoples.”15 The autonomy of the Basque country or the Zapatistas is thus a victory for the possibility of internationalism worldwide. This certainly does not mean that stateless internationalism sidesteps the concrete material struggle for a territorial space, and all the very concrete infrastructural questions of governance, security, and so forth that come with it. However, this space is not a goal in and of itself, but a space through which a stateless internationalism is articulated.

This is what—at least in theory (or better: all too often only in theory)—fundamentally differentiates the historical struggles for national liberation from ultranationalism. Whereas the latter regards separation from others as a victory, the former treats self-determination as one of many steps towards articulating an internationalist commons. That is not to say that national liberation movements cannot turn out to become expressions of ultranationalism, or that the struggles of other stateless entities cannot be easily forgotten once the goal of independence is obtained. The fundamental underlying idea here is if the concept of liberation and the concept of the state can coexist.

Fadile Yıldırım, a representative of the Kurdish Women’s Movement, has attempted to deepen the conflict surrounding the role of the state within national liberation movements. “We started our struggle against the Turkish state,” she has said. “But later we realized it was not just the matter of the repression of the Turkish state.”16 Yıldırım realized that there was a systemic inequality between men and women within the Kurdish struggle, which resulted in, among other things, restrictions against women becoming fighters. Women were expected to dedicate themselves to domestic work instead. Yıldırım concluded that “the enemy is not just outside, … we also have an enemy inside.” The result was that “the Kurdish women’s freedom movement started inside the national liberation movement.”17 For Yıldırım, national liberation is not a goal in and of itself. It is within this struggle that the very idea of the state as the endpoint of the movement for self-determination, freedom, and emancipation must be confronted:

We Kurdish women saw that if we want to be free we have to be independent. We realized that women represent the first class of slaves, and also the first colonized class. So we said if the first class and the first oppressed sex in history and society are women, than history and society can only be liberated by women. We believe that female liberation is only possible in a society where there is no state, no hierarchy and no power, where these structures are overcome. If we look at other national liberation movements or if we look at the Soviet Union we see that all revolutionary organizations that could not manage to do their own revolution inside looked like the enemy.18

So whereas the forces of ultranationalism use parliamentary processes to dismantle the state in the name of the state and replace it with unaccountable corporate-style structures of power, Yıldırım defends the radical opposite. She attempts to save the idea of democracy—defined as radically differentiated and fundamentally equal peoples—by liberating it from the state.19

Scholar Dilar Dirik, a prominent voice in the Kurdistan Communities of Woman (KJK), describes the concrete practice of this liberation in relation to Rojava (Syrian-Kurdistan) as following:

In the midst of the Syrian war, the people there created self-governance structures in the form of three autonomous cantons. These have 22 ministries with one minister and two deputies each, one Kurd, one Arab and one Assyrian, at least one of which has to be a woman. Several schools, women’s academies, working, living, and farming cooperatives, and women’s and people’s councils have been established.20

The state, as both Yıldırım and Dirik claim, is a patriarchal construct, and as such, it is unable to recognize the right to self-determination and the equality of women, for the subjection of one class to another is inherent to the state’s very creation.21 It will come as no surprise that it is the stateless Kurdish movement in Turkey and Syria—with a central role given to women in the fighting—that is currently battling the Islamic State in Iraq, as the army of the autonomous region of Kurdistan, the Peshmerga, were incapable of forming an effective front by themselves. On the one hand, the Islamic State explicitly opposes the colonial borders of Iraq, and thus forces into public consciousness the history of foreign occupation, military intervention, and extralegal prisons that created the conditions for and in some ways legitimacy of the organization.22 On the other, the Islamic State also functions—from the perspective proposed by Yıldırım and Dirik—as the unlimited patriarchal construct of the total state in the form of the ever-expanding caliphate. The performative gestures of Islamic State fighters publicly destroying their passports and thus allowing no administrative way back, as can be seen in their latest film The Clashing of the Swords IV, actually oppose statelessness and commit to one absolute and total state.23 The fear of humiliation amongst Islamic State fighters that they might be killed by a woman is the fear of losing their martyr status: it means they would be infected by statelessness, and lose all privilege and status in the total state.24

Yıldırım’s proposition to liberate democracy from the state embodies what the Concerned Artists of the Philippines consider the practice of the cultural worker: he or she who upholds discursive or pictorial histories through cultural practice, as an alternative to the powers that be which attempt to impose cultural amnesia in order to secure their rule. The cultural worker opposes the erosion of the possibility of history as such. This is a struggle that Professor Jose Maria Sison, founder of the Communist Party of the Philippines and the New People’s Army, would refer to as the struggle of the cultural worker against cultural imperialism.25

However different the struggles of Marcos, Lekue, and Yıldırım may be, what they share is their defense of a self-determination that, while remaining stateless, is first and foremost a militant cultural struggle. They are the representatives of stateless states—of peoples that precede their administrative representation in the formal, recognized entity of a state.

According to Sison, the cultural worker uses the tools of art in order to uphold the narratives and convictions of those who are marginalized, dispossessed, and persecuted by the militarized state. He or she is an educator, agitator, and organizer, all in order to maintain and to enact—to perform—the symbolic universe of the unacknowledged state that is not so much an administrative entity as a collective condition. The long cultural struggle of the Filipino people has created a state in itself, a detailed network of references, histories, and symbols that define a people’s identity far beyond what a state could ever contain. We are speaking here of art’s stateless state.26

It is within this stateless state that we find the condition that may be understood as a “permanent revolution” of stateless internationalism—that is, the permanent process of collectively inscribing, criticizing, contesting, and altering our understanding of communal culture. The cultural work of stateless internationalism helps to reimagine and create new and parallel political structures.

To Make a World

We are witnessing two forms of statelessness: the rise of ultranationalism, which ultimately manifests itself in political structures outside of public control; and the resurfacing of stateless internationalism, a political struggle that attempts to redefine a common culture beyond territorial and ethnic demarcations. The latter has its historical base in movements of national liberation, but tries to think and act itself beyond the nation-state.

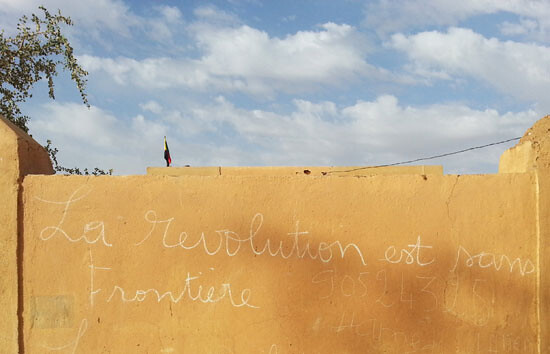

Around the time of the European election, writer Moussa Ag Assarid, the European representative of the National Liberation Movement of Azawad (MNLA) and previous contributor to the summit, contacted me. He was calling from Kidal, a city in the north of what is currently considered the state of Mali. In early 2012, the nomadic Kel Tamasheq people—better known as the Tuareg—led a rebellion in the north. The Tuareg, who have engaged in three earlier armed struggles against the Malinese state since the latter gained independence in 1959, had grown tired of failed treaties, a systematic denial of civil rights, repression, and violence. They are now demanding full independence. With the help of weapons taken from the crumbling Gaddafi regime, the MNLA, which consists of Songhai, Arab, and Fula peoples along with the Tuareg, declared two-thirds of northern Mali to be the independent state of Azawad. But a coup by Islamic groups, which included Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, undermined the MNLA’s control over the region and led France, Mali’s former colonizer, to invade the northern region in order to “stabilize” it. The French were eventually replaced by the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA), which is still ongoing.27

When I initially met Ag Assarid some years ago, I asked what exactly the homeland of the Tuareg was. As a response, he drew a large circle on a map, crossing through Algeria, Niger, Burkina Faso, Mali, and Libya—not a state but a space; although ruled under tribal policies and strict class separations, that the MNLA does not tend to glorify all too much today. So far, the Tuareg populations in several of these countries have demanded an independent homeland. In Mali, the recent declaration of the independent state of Azawad was the fourth attempt to declare independence since Mali was colonized by France in the late nineteenth century. Each attempt articulated a new state, because this is the language that geopolitics might understand and recognize as legitimate. But the attempt to speak in the language of states is the result of the historic colonization of the territory by the same army that now wishes to “stabilize the region”: a self-replicating language of territorialization, separation, and administration. The nomad state—the nomadic parliament—might be a first articulation of a stateless state. Not a Deep State, but a liberation through the state from the state.

I received the call a day after the Malinese government declared war on the Tuareg once more. Fights had broken out in Kidal, and the MNLA had taken control of the city.28 Ag Assarid listed for me the things they had won in the battle: camouflaged 4×4 trucks, an ambulance, and prisoners, who they released some days after. The only problem was that there was no one to report on the conflict; no media or journalists were present, and a media outlet had once told him that independence would only come if “CNN would broadcast you.” He thus asked for phones with a large storage capacity that could film, photograph, and upload, ideally through a satellite connection. It was not in the concrete day-to-day fight that the MNLA was in need of help from outside: Assarid had once laughed while telling me how the Malinese army, which is unfamiliar with the rough northern territory, would at night mistake stones and goats for enemies, and out of confusion would start shooting at each other. As Assarid said, one hardly needs an army to defeat these opponents, since the terrain suffices. The problem was not liberation, but representation. Azawad is off the grid: most of its citizens are not part of any outside administrative entity, and thus cannot travel. Further, there is hardly any running water, electricity, or paved roads, let alone effective phone signals or internet.

Writer and politician Upton Sinclair wrote that the goal of the artist at the dawn of internationalism was not to “make artworks,” but to make a world.29 This is exactly what seemed to be at stake here: contributing to the conditions of representation after liberation—to the possibility of future history. Is that not the task of any cultural worker?

This is the art of the stateless state.

In Hungary and Greece, the paramilitary fascists (respectively Jobbik and Golden Dawn), with which even the National Front is unwilling to collaborate, gained strength.

Vivienne Walt, “Inside Job,” TIME, May 26, 2014.

Peter Dale Scott, American War Machine: Deep Politics, the CIA Global Drug Connection, and the Road to Afghanistan (Lanham, Maryland: Roman & Littlefield, 2010), 2.

Nafeez Mosaddeq Ahmed, “Capitalism, Covert Action, and State-Terrorism: Toward a Political Economy of the Dual State,” in The Dual State: Parapolitics, Carl Schmitt and the National Security Complex, ed. Eric Wilson (London: Ashgate, 2012), 53.

Wilders’s chief ideologue, Martin Bosma, bases his use of the term “sleeper cells” on the Islamic concept of “takiyya,” which says that Muslims can hide or deny their faith if they are at risk of persecution. Bosma distorts this concept to claim that European Muslims are hiding their actual intention—namely, to implement Sharia Law in Europe—until they have gathered enough strength to do so. See Martin Bosma, De schijn-élite van de valse munters: Drees. extreem rechts, de sixties, nuttige idioten, Groep Wilders en ik (Amsterdam: Uitgeverij Bert Bakker, 2010).

Geert Wilders, column at www.pvv.nl, October 30 2007, translated by the author. In the column, Wilders emphasizes that the model of preemptive detention is borrowed from the Israeli model of “administrative detention,” which Stephanie Cooper Blum, attorney for the Department of Homeland Security, describes this way: “In 1948, when Israel achieved its independence, Israel adopted the British Mandate’s Defense (Emergency) Regulations of 1945, which empowered the High Commissioner and Military Commander to detain any person it deemed necessary for maintaining public order or securing public safety or state security. In 1979, Israel reformed its detention laws and enacted a new statute: the Emergency Powers (Detentions) Law of 1979 (EPDL of 1979), which provided more rights to detainees than the prior regulations … While the EPDL of 1979 only applies once a state of emergency has been proclaimed by the Israeli Knesset (Israel’s legislature), Israel has been in such a state of emergency since its inception in 1948.” Stephanie Cooper Blum, “Preventive Detention in the War on Terror: A Comparison of How the United States, Britain, and Israel Detain and Incapacitate Terrorist Suspects,” Homeland Security Affairs vol. IV, no. 3 (October 2008).

In 2007, Wilders’s Freedom Party proposed banning the Quran, which he has described as the “Islamic Mein Kampf” (Geert Wilders, “Genoeg is genoeg: verbied de Koran,” de Volkskrant, August 8, 2007.) In 2010, a prohibition on headscarves in public buildings was part of the program of the Freedom Party in northern Holland.

Ben Hayes, Chris Jones, and Eric Töpfer, Eurodrones Inc. (Statewatch Transnational Institute, 2014), 9. See →.

Ibid., 8.

“During the last two years Frontex has been a regular participant in forums promoting the securitisation of border controls in Europe, alongside groups lobbying in favour of corporate interests such as the Aerospace and Defence (ASD) association, which promotes the aeronautics industry as a strategic priority for Europe, and the Security Defence Agenda (SDA), a Brussels based think tank that provides a platform for the meeting of EU institutions and the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) with government officials and representatives of industry, international and specialised media, think-tanks, academia and NGOs.” Apostolis Fotiadis, “Drones may track migrants in EU,” Al Jazeera, Nov. 11, 2010 →.

See Trevor Paglen’s Blank Spots on the Map: The Dark Geography of the Pentagon’s Secret World (London: New American Library, 2010). The phrase also brings to mind the frustration of Dutch journalists who attempted to acquire documents providing insight into the involvement of the Netherlands in the Iraq War. When the journalists finally received the documents, they were censored with white ink, thus making the censorship itself invisible.

I think it’s possible to argue for important historical ties between stateless internationalism and the manner in which models of political emancipation and direct democracy are being developed within other acknowledged political parties such as Syriza in Greece, the international Pirate Parties that entered the EU parliament in Iceland and Germany, the rise of new Green Parties throughout the EU, and the Feminist Initiative in Sweden.

Subcomandante Marcos, “Tomorrow Begins Today” (August 3, 1996), in Our World is Our Weapon: Selected Writings (New York: Seven Stories Press, 2001), 118.

This is quoted, with Lekue’s permission, from a personal conversation I had with him in Berlin in summer 2013 about the future of the state in progressive politics.

Sortu, “Foundational Congress: International Resolution,” February 23, 2013 →.

Fadile Yıldırım , “Women and Democracy: The Kurdish Question and Beyond,” lecture at the first New World Summit, May 4, Sophiensaele, Berlin. See →.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Reflecting on the first Gezi Park protests one year after they broke out in Istanbul, philosopher Michael Hardt followed up on the rarely theorized practices of the Kurdish movement in relation to modern democratization movements, commenting that “An entire generation of activists across the globe has oriented its political compass toward Chiapas (home base of the Zapatistas). Why has so little international attention been focused on the Turkish Kurds?” Hardt continues: “Key to the current situation, as I understand it, is the fact that roughly a decade ago the stream of the Kurdish movement that follows Abdullah Öcalan radically shifted strategy from armed struggle aimed at national sovereignty toward the development of ‘democratic autonomy’ at a community level … I can see a vague correspondence between the roles of Marcos and (Abdullah) Öcalan (the imprisoned founder of the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK)), who is a kind of shadow leader that from prison periodically delivers somewhat poetic pronouncements that are interpreted by followers. The substantial and important point of contact, though, is the experimentation in village communities to practice a new kind of democracy.” Michael Hardt, “Innovation and Obstacles in Istanbul One Year After Gezi,” euronomade.info →.

Dilar Dirik, “The ‘other’ Kurds fighting the Islamic State,” Al Jazeera, September 2, 2014: →.

As Abdullah Öcalan has written: “When nationalism degenerated into secession and practically into a new religion, it became reactionary. The chauvinist thinking in nationalist terms, with its claims of superiority over other peoples and nations, became the cause of new hostilities. We now find wars between ethnically defined nations. As class struggles became fiercer, the capitalist class increasingly used these ideologies for their own purposes, hiding their true interests behind the mask of the nation.” Abdullah Öcalan, Prison Writings: The Roots of Civilization (London: Pluto Press, 2007), 200.

Tim Arango and Eric Schmitt, “U.S. Actions in Iraq Fueled Rise of a Rebel,” New York Times, Aug. 10, 2014 →.

See The Clashing of the Swords IV.

“The fact that Kurdish women take up arms, traditional symbols of male power, is in many ways a radical deviance from tradition … Being a militant is seen as ‘unwomanly,’ it crosses social boundaries, it shakes the foundations of the status quo. Militant women are accused of violating the ‘sanctity of the family,’ because they dare to step outside of the centuries-old prison that has been assigned to them. Because they turn the system, the patriarchal, feminicidal order upside down, by becoming actors, instead of remaining victims. War is seen as a man’s issue, started, led, and ended by men. So, it is the ‘woman’ part of ‘woman fighter,’ which causes this general discomfort.” Dilar Dirik, “The Representation of Kurdish Women Fighters in the Media,” Kurdish Question →.

Jose Maria Sison, “Cultural Imperialism in the Philippines,” in Towards a People’s Culture, ed. Jonas Staal (Utrecht: BAK, Basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht, 2013), 21. Full download here →.

I have attempted to deepen the concept of cultural work as the rearticulation of the state through art in my introduction to the collected poetry of Professor Sison. See Jose Maria Sison, The Guerilla is Like a Poet (The Hague/Tirana: Uitgeverij, 2013).

The only proper reporting on the war between Azawad and Mali has been done by Al Jazeera, whose documentary Orphans of the Desert provides full coverage of the conflict since 2012, including interviews with representatives of the MNLA and with rival groups such as Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb. The webpage for the documentary includes regular updates. → For Security Council resolution 2100 of April 25, 2013—intended to support the political processes in Mali and carry out a number of security-related tasks—See →.

“Mali ‘at war’ with Tuareg rebels,” Al Jazeera, May 19, 2014 →.

“The artists of our time are like men hypnotized, repeating over and over a dreary formula of futility. And I say: Break this evil spell, young comrade; go out and meet the new dawning life, take your part in the battle, and put it into new art; do this service for a new public, which you yourself will make … that your creative gift shall not be content to make art works, but shall at the same time make a world; shall make new souls, moved by a new ideal of fellowship, a new impulse of love, and faith—and not merely hope, but determination.” Upton Sinclair, Mammonart (San Diego: Simon Publications, 2003), 386.

Category

I would like to thank philosopher Vincent W. J. van Gerven Oei, Professor Jose Maria Sison, Jon Andoni Lekue, Moussa Ag Assarid, and Dilar Dirik for their advice in writing this essay.