It was already midnight when Sturtevant appeared at my Frankfurt apartment with flamboyant hair and dressed to kill. What an extravagant, outrageous lady! This was a decade ago, but for some reason I remember that it was 4:20 in the morning when she and curator Udo Kittelmann, who had brought her, finally left in a taxi. That was nothing special in those art academy days, when nobody ever wanted to go to bed, but her stories about playing tricks on Marcel Duchamp and embarrassing Andy Warhol with dirty jokes made quite an impression. Some weeks later she gave a weirdly robotic talk for the students of the Städelschule, where I was then director, and dismissed every question from the audience as too dumb to even consider. She had just opened a major retrospective at the Museum für Moderne Kunst, and was spending a few weeks in our German town. At that opening she was in the best possible spirits and treated me as a friend. Fans from all over the world had arrived, and I remember being introduced to critic Bruce Hainley, the true expert on her work. He was working on Under the Sign of [sic], the brilliant book that has finally appeared and which anyone interested in Sturtevant’s work should read.1

Many artists were there to pay her homage. Michael Riedel arrived with a white lily that he placed on the table in front of Sturtevant without uttering a word. Those were the days when Riedel was confusing German audiences, drawing them into a world of echoes, afterimages, and replicas. Using strategies of doubling and inversion, he created a kind of parallel universe—simulacra that were never merely mechanical copies but rather creative restagings of entire exhibitions by others. Sturtevant seemingly had no clue what the flower on the table signified or who had put it there. All the same, in an articulate conversation with Hainley the year before, she had succinctly spelled out what our present artistic condition is all about and how it makes art like hers (and Riedel’s) pertinent: “What is currently compelling is our pervasive cybernetic mode, which plunks copyright into mythology, makes origins a romantic notion, and pushes creativity outside the self. Remake, reuse, reassemble, recombine—that’s the way to go.”2

I remember reading this conversation later and realizing that Francesco Bonami and I definitely should have included her in our “Delays and Revolutions” that formed the center of the 50th Venice Biennale, and started with Warhol’s screen test showing a wry Duchamp (1964–66) and his doubling of the screen in Outer and Inner Space (1965), and culminated in works by Cady Noland and a vast gallery full of Richard Prince’s rephotographed Cowboys. How could we have overlooked Sturtevant in this labyrinthine meditation on repetitions, duplications, and simulacra? Unforgivable! I didn’t know her personally then, but I had seen her work as early as 1989 at Christian Leigh’s legendary “The Silent Baroque” at Galerie Thaddeus Ropac in Salzburg. A few years after this extravaganza Leigh himself disappeared mysteriously, like Duchamp’s original urinal, now known only as a photograph. The last sign of him I can remember was a ghostly portrait in the New York Times and a story about some vanished artworks and his own disappearance. No one knew what happened to him, not even Sturtevant, and to me his strange fate become part of her simulacral art, with all its enigmas and uncertainties:

Dear, dear Christian, with his keen and intense face—so clever, so fast, so funny, so bad. He played out fantasies in the murky art world that would have played out better on the dramatic stage. He was a super talented guy, with critical panache, who made twisted turns that sucked him up—and that was that. As for where he is now: Maybe he’s a master samurai in Tokyo.3

After years of studio visits, openings, and hilarious dinner parties, I feel that I did know her well, and yet so much remains uncertain. Very little is known about her background, and she officially only used what we all assumed was her last name. Her best friends called her Elaine, and I started doing that too. Was she really turning ninety this summer, as the obituary in the New York Times claims? Many years ago, this maze of ambiguities prompted Pop art historian Tilman Osterwold to write, “Perhaps everything that was ever written about Sturtevant is wrong. Perhaps that is her strategy.”4

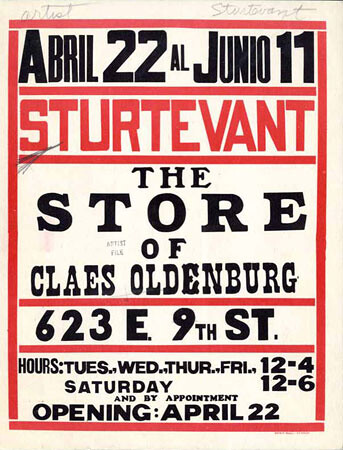

Some basic facts seem certain: Sturtevant made her debut in 1965 with an exhibition at the Bianchini Gallery in New York presenting Warhol’s silkscreen prints of flowers. A plaster figure offered a clothes rack full of other paintings by male colleagues Frank Stella, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, and Roy Lichtenstein. The general reaction was not one of enthusiasm. Some of the artists were pissed off, others took it calmly. Predictably, Warhol was the coolest and invited Sturtevant into the factory to use his original silkscreen and other tools to create perfect replicas. At some point, after being questioned over and over again about his process, Warhol famously replied: “I don’t know. Ask Elaine.” On the whole, Sturtevant was dismissed by the critics, and in 1974, after years of frantic activity, she decided to stop producing exhibitions. She turned to tennis. This was to give the “retards” time to catch up.

It wasn’t until this last decade that the institutional world finally caught up—she was given large institutional shows in Frankfurt, Paris, Zurich, London, and Stockholm. As Fredrik Liew, the curator of the Moderna Museet exhibition, pointed out, we should remember that her debut exhibition was made several years before Roland Barthes’s essay “The Death of the Author” (1967) and Michel Foucault’s “What is an Author?” in 1969, two texts which are often invoked to make sense of her art. The critical literature that would give Sturtevant her intellectual framework was not written yet, so no one can accuse her of simply illustrating philosophical ideas formulated by others. She really was ahead of her time. The Moderna Museet, with its history as a key institution for Duchamp, Warhol, and the whole Pop era, was the ideal place for a large exposé, and we made the rather extreme decision to open the show with no other artists’ work displayed in the entire institution. There were no originals in the museum, only repetitions. Needless to say, the artist was pleased.

Sturtevant’s repetitions never look back, they look ahead. They have nothing to do with revival and return, nothing to do with nostalgia, but are instead turned toward the future: repetition as difference, repetition as production of the new. Here repetition is the opposite of recollection. As Sturtevant was well aware, Kierkegaard, in his essay Repetition, had already made this clear: “repetition and recollection are the same movement, except in opposite directions, for what is recollected has been, is repeated backward. Repetition, therefore, if it is possible, makes a person happy, whereas recollection makes him unhappy.”5 Jacques Lacan characterized this essay as “so dazzling in its lightness and ironic play, so truly Mozartian in the way, so reminiscent of Don Giovanni.”6 That lightness is also Sturtevant’s. Her most recent video pieces, works like Elastic Tango (2010), which no longer repeat individual colleagues’ art, seem so much a part of our moment that they could have been produced by an artist in her twenties. There would be nothing strange in presenting a recent video of hers with works by Simon Denny, say, or Helen Marten.

“The current moment was yesterday,” she told me, always one step ahead of the rest of us. The artist who most stubbornly questioned our notions of originality turns out to be one of the truly original ones. How is that possible? I don’t know, ask Elaine.

Bruce Hainley, Under the Sign of [sic], (Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2014).

“Sturtevant Talks to Bruce Hainley,” Artforum vol. 41, no. 7 (March 2003).

Ibid.

Quoted in Sturtevant: Image over Image (Cologne: Walter König, 2012), 42.

Søren Kierkegaard, Repetition, A Venture in Experimental Psychology by Constantin Constantius, trans. Howard V. Hong and Edna H. Hong (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1983), 131.

Jacques Lacan, The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psycho-Analysis, ed. Jacques Alain-Miller, trans. Alan Sheridan, (New York: W. W. Norton, 1998), 61.