If you take a close look, you can see it.

With The Atlas Group (1989–2004), I spent fifteen years working on a project about the wars in Lebanon. I have known and I have seen how the Lebanese wars of the past four decades have affected Lebanon’s residents physically and psychologically—from the one hundred thousand plus who have been killed, to the two hundred thousand plus who have been wounded, to the million plus who have been displaced, to the even more who have been psychologically traumatized.

I have also seen and I have known how the Lebanese wars of the past four decades have affected Lebanese cities, their neighborhoods, buildings, and streets. But what I had not considered was how the wars can also affect colors, lines, shapes, and forms.

Some of these colors, lines, shapes, and forms are affected physically, and, like burned books or razed monuments, they are materially destroyed and lost forever. We can never access them again.

But others are affected in a more subtle way. They are not destroyed. They are not removed from view. And yet these colors, lines, shapes, and forms are all of a sudden and for unknown reasons treated by some artists, writers, thinkers, and others as though they had been affected physically. Though they have not been physically destroyed, some sensitive people treat them as if they had been destroyed.

Let me give me you an example: a painter paints for years using only a particular shade of red. She paints monochromes with this red. Monochrome after monochrome. We are familiar with such painters. But one day she stops using this shade of red in her paintings. Were you to visit her studio, you would find it filled with the red paint tubes she has always used, as she did not stop using this shade of red because the color is no longer being manufactured. Considering that artists tend to go through phases, she might simply be in her blue phase, or her yellow phase, or perhaps she just does not want to deal with colors anymore. But then dozens of years later, and tens of artworks later, this shade of red still does not appear in any of her artworks.

Now her family begins to worry. They think maybe she is getting old; that her eyes are weakening. So they send her to consult an ophthalmologist. The ophthalmologist tells her that her eyes are fine, and that maybe she should consult a therapist. She consults a psychoanalyst, and after a few months her analyst tells her she is as healthy as anyone else. However, I am convinced that this woman, this artist, must have sensed all along that the blockage was never in her eyes. It was never in her psyche. The block was in the color. The color has been affected and is no longer available. That’s all. And the artist may know this, or, rather, she may feel it.

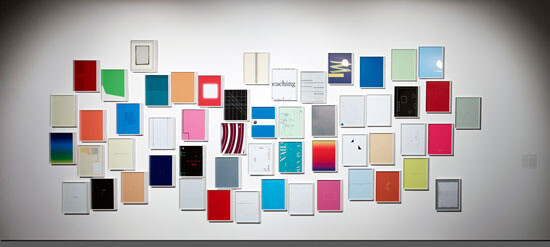

But then there are instances—as you can see with the accompanying plates—when some colors, lines, shapes, and forms can sense the forthcoming danger. And when they sense it, they deploy defensive measures: they hide; they take refuge; they hibernate, camouflage, and dissimulate. Of course, I had expected that when they hide, they do so in the artworks of past artists. I had thought past Master paintings, sculptures, drawings, and buildings would be their most hospitable hosts. But I was wrong.

Instead, it seems that when some colors, lines, shapes, and forms sense the forthcoming danger, they somehow just leap, or jump, or drift, or somehow “abandon” their present location to take refuge in certain documents that circulate around artworks. They are no longer within those artworks, but in documents that circulate around them.

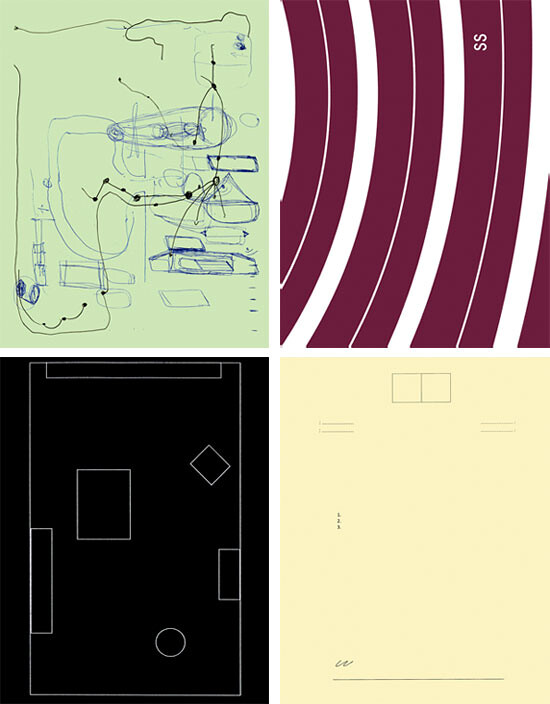

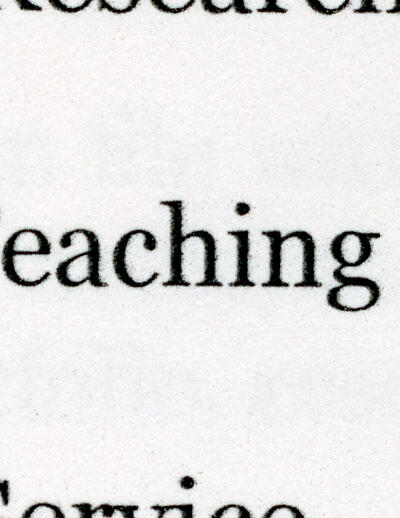

For example, they might go into a dissertation. In fact, they seem to be quite fond of academic dissertations, especially the ones written by foreigners on a native culture and in a foreign language. They love to go there. For example, take one of the first dissertations written in English on Lebanese modernism by an American anthropologist at an American university. Many colors came here.

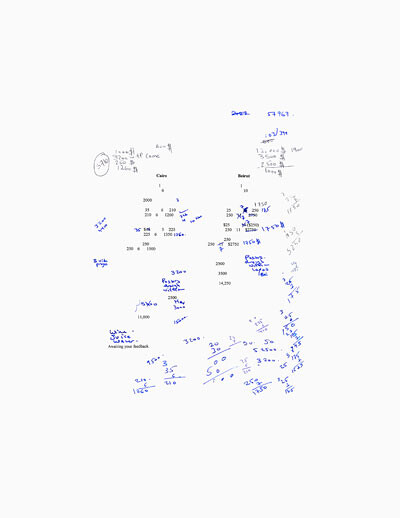

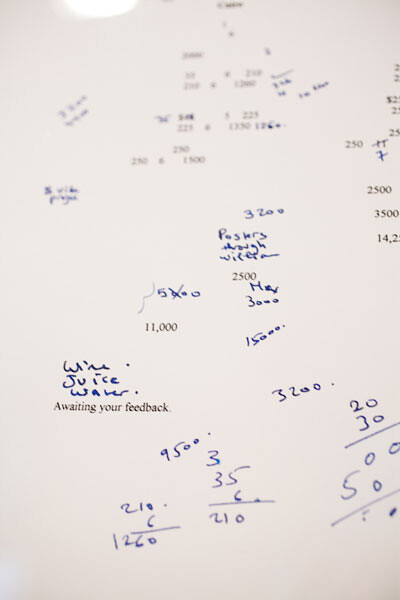

From time to time, lines camouflage themselves in budgets, especially those that itemize the costs of cultural exchanges between two Arab cities: Cairo and Beirut for instance.

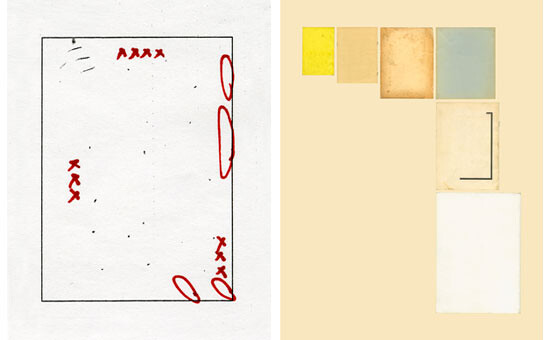

Shapes hibernate in letterheads, such as this gallery’s letterhead for instance, which is on a letter written by a Lebanese gallery to the Lebanese minister of culture requesting the first Lebanese National Pavilion in Venice in 2005. Shapes hibernated here.

Forms are drawn to the graphic logos of companies that support the arts, providing condition reports, floor plans, business cards, price lists, catalogue covers, indices, appendices.

Now, if we observe the budget, do we find numbers? Absolutely not. These are lines disguised as numbers.

The condition report? No. This is a shape taking refuge within a condition report.

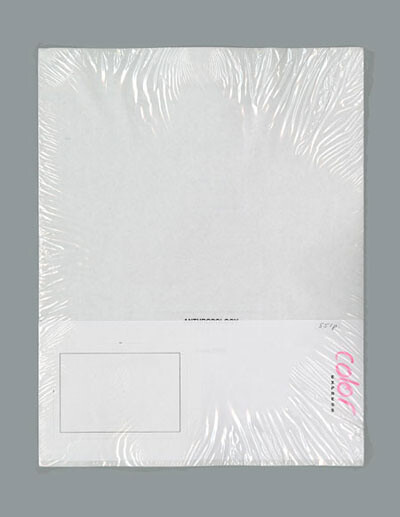

And this is not a book, but a form dissimulating as a book.

And of course, this is not blue.

This is not yellow.

This is not black.

These are the colors, lines, shapes, and forms that compose the fifty-four plates displayed here.