The Triad of Perversity

History repeats itself. There is no event that disappears without a trace. Everything we experience returns in a new context, in a different form; time and space make up a multi-dimensional complexity where everything that has happened is enfolded in collective memory, waiting for the proper moment to unfold itself and reappear as mutation. But the interconnectivity of events is expanding and growing more dense, to the extent that it is exceeding our grasp.

The mess of current political conflicts that are devastating people’s lives across the globe internalize increasingly multiplied forces. These forces include not only those identified as left or progressive—mass movements for revolutionary transformation or reform—but also those identified as right or tradition-oriented: i.e., religious fundamentalism and ultranationalism. When struggles for independence waged by ethnic and religious minorities confront increasingly repressive states, nationalism inexorably surfaces in both camps—among the rulers and the ruled. The limits of representative democracy are thereby exposed, and the noise of unfolded history rushes in to fill the void. This is happening not so much within political institutions as across the social field. In other words, previous articulations of political tendencies get jumbled up, and are then set loose by mediatized spectacles that speak to our desires. The flow of images, signs, and symbols is what seems to connect people both locally and internationally. These connections could develop in one of two directions: either towards the reverberating “Eros effect” of people’s uprisings (George Katsiaficas), or towards the spreading of xenophobic behavior, discourse, and culture.

In this situation, it is worthwhile to think through the perverse triad of totalitarianism, fascism, and nationalism in order to resituate the ontological status of people’s struggles and revolutionary projects. Both the struggles and the triad are born of the mess of existing social relations and conformity, involving the collapse—or original impossibility—of political representation (Marx and Schmitt). They are both ways to exploit fissures within the organization of power, but at the same time, they diverge significantly: while the struggles seek to reorient the situation toward the liberation of all our existential territories—mind/body, society, and environment—the triad embodies the will to be captured by a single territory, that of the oppressor, be it the state, the nation, or religion.

In this context, I would like to offer notes on the triad that provides the basis for blood and soil in Japan. This triad persisted even after the defeat of the imperialist regime in World War II, surviving through the country’s postwar democracy, and continuing up to and beyond the Fukushima nuclear disaster. Along the way, the triad has undergone a series of monstrous mutations.

Virtual Totalitarianism After the War

Totalitarianism is a political system based on dictatorship and bureaucracy; fascism is a form of micro-organization that pushes nationalism to the extreme, toward a single destiny for all; nationalism provides both totalitarianism and fascism with the affective territory of engagement, operation, and control. They often work in ensemble, aiming at the radical extinction of the differences in our existence. In Nazi Germany, the state apparatus was taken over by the fascist machine—rather than vice versa—which fueled the death drive of the entire nation. “How else are we to understand the way they were able to keep the war going for several years after it had been manifestly lost?” (Félix Guattari) So too in imperialist Japan, the slogan of “all die rather than surrender” rallied the nation to sustain the regime of emperorist fascism, even after defeat on all fronts, from Manchuria to East Asia to the Pacific, up until the unprecedented atrocity in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Japan’s unconditional surrender came in 1945. The fascist officers of the Imperial Japanese Army, who had sought to realize “all-nation death,” either committed suicide or were hanged. The totalitarian regime was dismantled by the US occupation forces, which subsequently imposed “democratic reforms,” such as the new constitution (the so-called “peace constitution”) and land reform. At the same time, however, the occupation forces exempted a number of first-class war criminals and recruited them to redeploy their influential status across the apparatuses, in order to create an allied regime to confront America’s new enemies on the Asian continent. Most notably, the emperor himself was excused from being tried on the order of General MacArthur, who grasped that Japan’s social conformity had always been reassembled in different historical junctures by summoning the emperor’s symbolic power. From the feudal domains, to the modern absolutist state, to the postwar democracy, all forms of sovereign power were able to rule the populace as “Japanese” by filling the emperor’s place as the “empty sign” (Roland Barthes) with their forms of governance.

Thus, postwar nationalism was initially given territoriality of operation by the US military. Roughly three types of nationalism appeared thereafter: (1) anti-US nationalism, which formed not only the basis for the ideological Right, but also shaped certain antiwar, anti-imperialist, and revolutionary movements for “true independence” from the US, especially during the Korean and Vietnam Wars; (2) anti-communist nationalism, which animated the most substantial part of the Right and the ruling power, at the same time as it enjoyed a broad appeal, from conservative politicians to the industrial and financial sectors to the military to the commoners; since the end of the Cold War, it has become a pro-US, anti-China, anti–North Korea ideology; (3) and the nationalism of commoners’ movements that consist of “molecular fascism” (Deleuze/Guattari), e.g., xenophobic citizens’ groups, unconditional emperor worshippers, and yakuza organizations that work as mercenaries for the ruling conservatives.

Emperor worship miraculously persists among a large part of the population, thanks to the media. It constantly reports the “private” whereabouts of members of the royal family. By ceaselessly watching them—how they grow up, go to school, vacation; get engaged and married; perform in public; make speeches of encouragement, sympathy, and mourning—the residents of the archipelago are supposed to affirm their Japanese identity. This is an imposed education in how to be a proper citizen, by way of disseminating amiable spectacles and narratives about the royal family—spectacles that the family members themselves are made to act out.

Although the totalitarian regime is gone, a totalitarian machine is still at work to articulate homogenous nationhood: this machine is the the so-called “symbolic emperor system.” Totalitarianism still exists virtually. In terms of producing the machine, one cannot ignore the role of the material apparatuses of the metropolitan network of Tokyo—centered around the Imperial Palace—which both expand and concentrate the circulation of commodities, information, and transportation to serve the gigantic economic apparatus. The impression, shared by many around the world, that the Japanese are homogenous is due to the tightness of the network, successfully realizing a society of concentrated fashion—of behavior, ways of life, cultural taste, and political ideas—that congeals the desires of the masses and orients them monodirectionally.

Pornographic Fascism in Postwar Democratic Japan

The restorative images of self-professed fascist groups—orderly marches, war songs, military uniforms, the Rising Sun, and so forth—are associated with the ultraright or with yakuza organizations. One of the most significant roles of fascist/yakuza organizations has been their violent oppression of radical labor movements in day-laborer ghettos (these include Sanya in Tokyo and Kamagasaki in Osaka), where they run underground labor-recruiting businesses under the guise of “emperor worship societies.” Although their conduct appears to be far from the serene life/performance of the royal family, these two cohabitate in the spectrum of operations of the ruling power, working equally toward the totalization of the society.

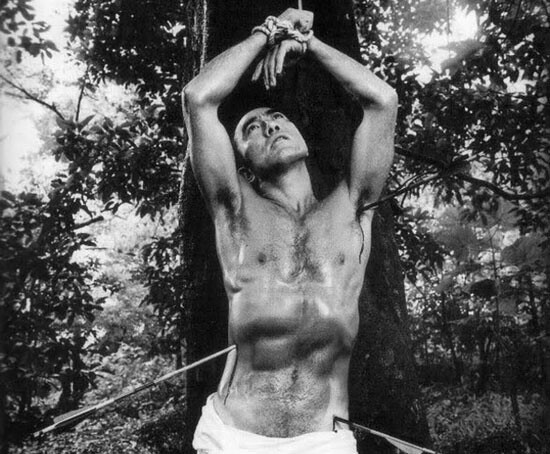

One of the most extreme experiences of postwar Japanese history was the coup attempt and the subsequent ritualized suicide of Yukio Mishima in 1970, carefully planned as a media event in collaboration with two of his comrades from the militia he founded, the Shield Society. His case first shocked and then puzzled many across the political spectrum. One ultraleft faction admitted that Mishima’s act has surpassed their own radicalism. A few ultraright thinkers praised it. But the majority of conservatives, including military officers, regarded it as too dangerous or a joke. Mishima was famous as a nuanced emperor-worshiper, a right-wing opinion leader, and, of course, a celebrated novelist, writing innumerable stories in a highly symbolic, decorative, and graphic style. At the same time, he was a multi-talented performer; he befriended and collaborated with such avant-garde artists as butoh dancer Tatsumi Hijikata, painter Tadanori Yoko-o, and singer/actress Akihiro Miwa. He was also known for his aesthetic and corporeal passion for homosexuality. Certainly, his existence and actions hardly fall into conventional categories of the political. But precisely for this reason—and with his narcissistic death drive and irrepressible desire to exhibit his dying body in extreme agony—he should be regarded as the fascist par excellence in the age of media/spectacle.

Since the bursting of the mid-’90s economic bubble in Japan, the promises of middle class life have been broken. The dream of having a home in the suburbs with two children and a car has faded. Through neoliberal reforms, the precarization of labor has spread across society. The signs of social decomposition have surfaced as frictions within various apparatuses. This situation has reinforced commoners’ fascistic drives, evident in everyday circumstances such as disciplining, bullying, and violence in families, school, and the workplace, and in society at large, in the form of the bashing of those who deviate from social norms (or fashions) and the hatred of (especially Asian) foreigners.

The mass xenophobic movement Zaitoku-kai (Citizens Against the Special Privileges of Resident Foreigners) was established in 2006 and remains active today. One of its main tactics is to use the internet (especially Twitter) and other media to loosely organize actions that are designed to get maximal public attention. The membership of this group no longer consists of mainly macho male fighters; it now includes “normal citizens” of varied age and sex—normal except for their use of racist language directed at resident Koreans, which they scream loudly in Korean residential areas and near Korean schools.

Among establishment conservatives, the denial of the Nanjing Massacre and of the use of Comfort Women is widespread, involving known politicians and academics.

I call this culture driven by nationalistic spectacles and the denial of historical facts “pornographic fascism.” It is based on a dynamic of revealing and hiding, of exhibitionism and denialism: revealing private life (of the imperial family), one’s own dying body (in media spectacle), and the graphic language of racism, while hiding the dirty secrets of history. Pornographic fascism is driven by the desire to perform martyrdom for the homogenized territory of the mass media.

Radioactive Nationalism in a Post-Nuclear Disaster Society

In Japan’s post-nuclear disaster society, the national death drive has manifested itself in three main forms: (1) working class suicide due to “Abenomics” (the economic policies of the current prime minister, Shinzō Abe); (2) antagonism toward other Asian countries; and (3) the project to reconstruct Fukushima and support the local economy by willingly consuming irradiated food.

By focusing on lowering the unemployment rate—largely through the introduction of work-sharing—Abenomics is making working conditions more and more unstable and disposable. It is transforming the entire working populace into “day-workers.” Many people expect that they will be ruined by overwork at an early age. But at least when it comes to statistics, Abe is surprisingly popular, with an approval rating of around 60 to 70 percent.

The Japanese government is increasingly isolated in East Asia, partly due to disputes with China over island territories, and partly due to provocative visits by Japanese politicians to Yasukuni Shrine, a shrine to Japanese war dead. Yet the government persists in its “nationalist pride” and in continuously serving US hegemony in the region (by invoking the right of “collective self-defense”).

In the wake of the Fukushima nuclear explosion, people have been exposed not only to radiation but also to massive spectacles and torrents of information. The strategy of the ruling powers—the government, the electric companies, and the media—is not the same as information control in totalitarian states. It seems instead to rely on a tactic of undecidability. These powers allow a flood of spectacles to be disseminated to the public (for instance, the endless watering of the crippled reactors) while indefinitely postponing any judgment about the truth of information that is put into circulation (especially concerning radiation contamination and its effects on living organisms). It is amidst this spectacle/information soup that the campaign “Eat and Support Fukushima” has emerged as the vanguard of a nationalist death drive, whose promoters include the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries; a number of supermarket chains; as well as some consumers. Here, the enabling condition is the social totality called Japan and its economic and industrial control over the wellbeing of individual bodies. Instead of supporting the evacuation of residents from the contaminated areas, the priority of the ruling powers is to reconstruct Fukushima by binding as many people as possible to that unlivable land. This drive is significantly encouraged by intellectual and cultural interventions as well (e.g., the Tourism Development Plan of the Fukushima Daiichi, Project Fukushima, and so forth).

There are at least three territories of interest involved in the reconstruction. First, the reconstruction is crucial for the local economy and local industries; second, for sustaining and reinforcing the functions of the metropolitan network (of Tokyo); and third, for preventing the global economy from sinking. These territories are messily intertwined at the moment. In order to properly rearrange them into a hierarchy (global, national, metropolitan, and local), the coming Tokyo Olympics in 2020 is to provide the best imaginable opportunity. Meanwhile, sustaining Japan’s nuclear power—even after the disaster and despite the probable recurrence of earthquakes—is still part of the government’s central policy, which is, after all, a must for a global regime that relies on endlessly developing nuclear energy and weaponry. That is to say, the triad of perversity—virtual totalitarianism, pornographic fascism, and radioactive nationalism—is subordinated to global capitalism.

One last word: damages from the ongoing nuclear disaster are not evenly shared among the populace. If the unending spread of radioactive nuclides and their coming effects on life forms can be called apocalyptic, then it is a “combined and uneven apocalypse” (Evan Calder Williams). It is experienced differently according to class, age, gender, region, and way of life. In this context, radioactive nationalism functions to make these experiences more combined and more even among the commoners, while reserving the “unevenness” for the ruling class. It is a call for further economic flourishing in exchange for the devastation of our existential territories—mind/body, society, and environment. The decomposition of these territories has already begun, eroding both our wellbeing and our social relations—which is the true battleground between revolutionary projects and the triad.