As of next September, Emory College is closing its Visual Arts Department. Dean Robin Forman wrote a letter dated September 14, 2012 communicating this to the faculty. The news recently hit Facebook via an Art and Education announcement of March 2014. I don’t know what exactly happened in the intervening two years, but the consequences of the retrenchment are far reaching.

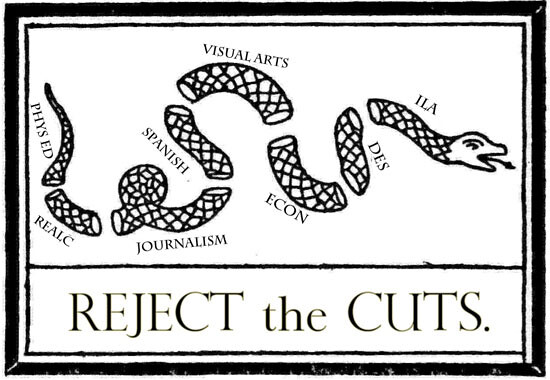

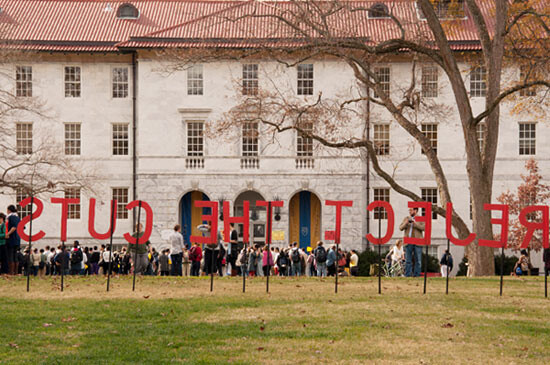

The dean’s letter is more interesting in what it implies than helpful in what it says. Forman is happy to underline the importance of the study of human health, quantitative theory, race, contemporary China, and the impact of digital media. He also mentions that the school currently has too many programs, with many of them stretched to the limit financially. (In 2011, Emory’s endowment was $5.4 billion, which was the sixteenth largest endowment among American universities that year.1 So it’s not clear what financially stretched means, exactly.) Later, the letter insists that the decisions are academic, not financial. The planned cuts go beyond visual arts; they also include the departments of educational studies, journalism, and physical education. In addition, admissions to graduate programs in Spanish, economics, and the Institute of Liberal Arts will be suspended.2 According to Forman, these decisions are necessary for Emory to “maintain its place as one of the top liberal universities in the nation.” Probably more important, the cuts and reallocations will also help “train the leaders of the century to come.”

I’m not a strong believer in art departments or art schools. Maybe Emory’s example is a good moment to examine their relevance. It’s not clear yet if Emory’s decision foreshadows the future of academia in the US, or if it’s just a passing fad. Either way, these developments at Emory raise crucial questions: What function do art schools fulfill? Do we really need them? In a lecture back in 2007, I referred to the institutional teaching of art as a fraud.3 I made the point that during my thirty-five years of teaching, I probably taught about five thousand students. These students financed my salary. Maybe about five hundred of them hoped to “make it” in the gallery circuit. Possibly twenty among these succeeded. That means that the other 480 hoped to make a living from teaching. Each one of them would in turn require another five thousand students to ensure their salaries. In only one generation, then, the needed student base went up to 2,400,000—and that was only considering my students, nobody else’s. No wonder this system is collapsing. In e-flux journal, Anton Vidokle used the term “pyramid scheme” to describe the system of art education, based on the fact that an MFA degree doesn’t even ensure employment to begin with.4

Looking at the issue from the point of view of fraud, Emory’s move to retrench visual arts could be interpreted as a step towards honesty and a perceptive reading of the market situation. The big flaw in the dean’s letter is that this point isn’t touched upon. We may therefore assume that guilt for past deception and false advertising did not play a role in the school’s decision. I’m not particularly interested in Emory, but since it’s rated number twenty in the U.S. News and World Report’s college ranking and charges $44,008 in tuition and fees ($8?), we should give its behavior some weight. It may be the canary in the coalmine.

Is there any reason that the arts should mingle among other disciplines? Emory’s decision treats art as a slice that doesn’t fit into the educational pie anymore. But perhaps it never should have. Does it make any sense to offer a degree that in some cases costs a quarter of a million dollars, but whose financial return is doubtful? When students used to come to me to register as visual arts majors, my first question was always: What on earth would make you want to do that? The ensuing conversation would often make me realize that I shouldn’t have become an artist. I should’ve become a shrink.

There are many professions where corporations prefer to ignore what a student learned in school. Instead, they train their own personnel as if starting from zero. Corporations have a better knowledge of the market. They have up-to-date information and the latest equipment. Schools, meanwhile, lag behind. They overpay presidents and have top-heavy, self-serving administrations. They hire star performers to improve public relations and fundraising, instead of hiring star teachers. To save money, they shift from full-time faculty to adjunct faculty. They use outmoded professional standards because the faculty ages but stays on. Depending on the discipline, they are often stuck with obsolete equipment.

Why don’t mega-galleries organize their own little art schools? This way, they could make sure that their stable of talent was regularly replenished with exactly the kind of artists they like to represent. I’ve always thought of the Whitney Independent Study Program as a forerunner to this; a museum shaping good producers of collectible artworks seems to bring everything full circle. Mega-galleries wouldn’t even need to conduct faculty searches. They could just hire from among their stable of artists. Teaching salaries could be covered with a modest 5 percent increase in the artists’ share of the revenue from the galleries’ sale of their artworks.

Most schools see themselves as feeding the gallery stables, but it’s not clear that they are the best place to do that. They filter students by trying to identify, like horses in a race, the best bets. That is, they identify those who need education the least, not the most. This handicap makes teaching less labor-intensive and cheaper. When they are conservative, schools focus on developing students’ skills (Painting 1, 2, and 3) and act as misnamed crafts schools. When they are progressive, schools teach students how to behave as an artist rather than be one, and how to fit smoothly into the system. Neither conservative nor progressive art schools that focus on artists as producers can claim that they are forming society’s leaders. That Bush, Putin, and Fujimori paint today, and that Eisenhower, Churchill, and Hitler did so in the past, helps much to support this claim.

The obsession with creating the leaders of the future seems consistent with the old trickle-down theory in economics. The problem is that leadership doesn’t trickle down. Concentrating on the formation of leaders and ignoring those that are supposed to be led actually destroys society. So, on less elitist platforms, we have to push to better all educational levels. But this time, we shouldn’t leave anybody behind just to make the US more competitive in the “global market.” To achieve the latter, Bush Sr., in his America 2000 program, asked for national testing in order to build a nationally unified education system. Clinton, with his Goals 2000 program, wanted US students to be first in the world in both science and math achievement, and also wanted every adult American to be literate and to possess the knowledge and skills necessary to compete in a global economy. Bush Jr. instituted No Child Left Behind with the same purpose, again giving priority to testing over education. Obama’s Race to the Top and his promotion of STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) continue this tradition, helping bury the humanities a little deeper. In spite of this two-decade effort, things haven’t worked out so well: the US is ranked 37th (averaging different indexes) on the international scale.5

“STEM” and “PISA” are the new favorite acronyms in education. The latter stands for “Program for International Student Assessment” and is sponsored by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). PISA is a system for evaluating international educational achievements.6 It ranks the effectiveness of the school system in about seventy countries, in the hopes that international competition will spur improvements in education. PISA is not really concerned with defining education. Their statistics are based on the performance of fifteen-year-olds in reading, math, and science. The PISA webpage speaks of “economies” rather than countries, a refreshing turn that challenges the geographically bound nation-state, but that also clarifies the purpose of the operation. The webpage states: “Aside from providing global rankings, analysts were [also] able to find out which educational systems are offering students the best training for entering the workforce of tomorrow, and why.” PISA has an overt economic, not a humanist, function. This explains the strangely limited material on which the statistics are based. By only studying fifteen-year-olds, PISA neglects to factor in students who repeat grades. More generally, this method doesn’t take into account societies concerned with extending educational access to hitherto neglected segments of the population lack the cultural context to be “good students.”7 Though PISA, to its credit, also emphasizes comprehension, the main strengths of art (speculation, imagination, and asking questions like what if?) have not been explored or used in conjunction with literacy or with the meaning of being educated. In 2012, PISA used “problem solving” as an added component for the first time. Only one-third of the usual countries were assessed, and the questions concerned everyday tasks in affluent situations: “identify the cheapest line of furniture in a catalogue,” or figure out “why a particular electronic device is not working properly.”8

Studies have shown that countries that receive a high PISA rating in mathematics are doing proportionally worse in creative entrepreneurship. The US, for example, has high entrepreneurship ratings, but its creativity has been steadily declining thanks to standardized tests and policies like No Child Left Behind. According to education scholar Yong Zhao, creative strength in the US decreased by 3.16 percent from 1990 to 1998, and by 5.75 percent from 1990 to 2008. “The ability to develop and elaborate upon ideas, detailed reflective thinking, and motivation decreased by 36.8 percent from 1984 to 2008.”9 America’s comparatively higher ratings in entrepreneurship are perhaps a consequence of its deficient educational system. Entrepreneurship is obviously not a synonym for artistic creativity, but it is the business world’s close equivalent, and there are more statistics available about entrepreneurship in the business world than about creativity in the arts. The art producer, meanwhile, is both an entrepreneur and a self-administered slave worker—hoping to become the former, but usually earning like the latter.

Maybe it is this hybridity that exempts artists from the situation described in graphs correlating productivity and employment that one can find on Google. They all show that starting in the mid-nineties, productivity increased as employment and wages declined. The typical artist suffers from this because of whatever second job he or she must have to survive, not because of being an artist. However, this reality is something that education officials around the world should take very seriously. It should in turn generate a discussion about the role of the arts in the educational process. A US government study conducted in 2008 determined that Americans born between 1957 and 1964 changed jobs more than ten times between the ages of eighteen and forty-two.10 This information alone should be enough to put the emphasis of education not on training, but on flexibility and the capacity to retrain (that is, on unlearning and learning as a combined action). It should bring to the fore the ability to think creatively and “out of the box.” Professional concentrations are not valuable anymore. While this doesn’t mean that we have to give up on them entirely, we do have to begin underscoring interdisciplinary connecting points that facilitate transitions. From this perspective, the present system, in which students must select a single area of focus, makes their choice into a career crap shoot. So, what combination of disciplines should students study? Medicine and auto mechanics? Architecture, dental hygiene, and watchmaking? Students should be prepared to constantly evaluate contexts and connections instead of being locked into a professional tunnel.

Meanwhile, in all of this, art is treated as a leisure activity. Although one may study it in school, it is during leisure time that art is normally produced and appreciated. Within capitalist ideology, leisure time is considered a time for consumption. It props up employment, since much of our leisure time is devoted to shopping and spending money. Even vacation time, which is merely a concession on the part of bosses to limit our exploitation, helps the economy: whatever our bosses lose on the production end with our absence from work, we pick up on the consumption end with our shopping. But just as art should be an area of free imagination unhindered by production, leisure time should be free from the requirement to consume. Thus, education should equip people as much for nonworking hours as it does for working hours. They are equally important, and only once this is understood will it make sense to link art and leisure.

Just as we should view art not as an accumulation of so-called art objects, but as a way of approaching knowledge, we should also view knowledge not as an accumulation of data, but as a flexible mechanism for reorganizing reality. Under present conditions, education should not focus on training, but on developing the ability to be constantly retrained. This means that learning should be combined with the skill of unlearning. Like computer software, we should know how to uninstall programs that we previously installed.

This approach to learning would democratize the relationship between teachers and students, since it would put teachers in the same position as students, or maybe even in a weaker one. Students would still be a tabula rasa, but teachers generally have ingrained habits which make uninstalling more urgent and more difficult. The main lesson, though, may be that we are seriously misusing art by forcing it to stay confined to a single academic department. Educationally speaking, producing artworks should be seen as a byproduct of a much more important process: learning to face the world with imagination rather than with submission.

We should treat art as a way of thinking, of acquiring and ordering knowledge, as a tool for subverting conventions in order to refresh and reshape culture. Art is the gluten in the dough, helping to hold the knowledge pie together. Our current educational system, however, seems to be gluten intolerant, with the corresponding symptoms of bloating, abdominal pain, and diarrhea. Art-thinking is speculation based on wonder. It has the advantage of being non-dogmatic, of not discarding anything except for the obvious and the trivial. Even chaos is part of this totality: nonlogical connections are as important as logical ones, and everything is available as we seek to construct new systems of order. From this point of view, art includes both science and magic: it doesn’t leave anything out.

Art is not situated in between; it is the umbrella that hovers over everything and includes everything. This inclusiveness makes art a meta-discipline, with science as one of its many subcategories. The obvious question then is, why can’t art-thinking be integrated into other ways of thinking? If we achieve this, we don’t need to fight to keep art schools going. We only need to change curricula, as well as some minds. With this we would achieve true liberal arts education. Meanwhile, I can only hope that our leaders in the century to come do not graduate from Emory.

Nick DeSantis, “Emory U. Will Close 3 Departments as Part of Broad Academic Restructuring,” The Chronicle of Higher Education, Sept. 14, 2012 →.

Lilly Lampe and Amanda Parmer, “Emory University Eradicates its Visual Arts Department, Portending an Ominous Trend in University Education,” Art and Education, March 2014 →.

Universidad de los Andes, Bogotá, Feb. 8, 2007. Published in Cuadernos Grises 4 (2009).

Anton Vidokle, “Art Without Market, Art Without Education: Political Economy of Art,” e-flux journal 43 (March 2013) →.

16th in livability; 70th in health; 69th in ecosystems sustainability; 34th in access to water and sanitation; 31st in personal safety; 39th in basic education. See Nicholas Kristof, “We’re Not No. 1! We’re Not No. 1!,” New York Times, April 2, 2014 →. The last line of the article continues with competitiveness as an aim: “The Social Progress Index offers a reminder that what is at stake is also the health of our society—and our competitiveness around the globe.”

PISA was created in 1997 by the OECD, which in turn was created in 1948 to help administer the Marshall Plan in Europe after the Second World War.

Gonzalo Terra, interview with Guillermo Montt, El País (Uruguay), August 18, 2013 →.

Motoko Rich, “American Students Test Well in Problem Solving, but Trail Foreign Counterparts,” New York Times, April 1, 2014 →.

Zhao, World Class Learners: Educating Creative and Entrepreneurial Students (Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin, 2012), 12.

See →.