In studies of repetition blindness, it is unclear whether the failure to recognize recurring items in a sequence owes primarily to an inability to notice similarities the second time something appears. Conflicting evidence indicates that it could just as easily involve an inability to remember the qualities something displayed the first time around. Psychologists are still split over this question.1

A person must first be allowed to perambulate a structure, eyes gliding along its surface. György Kepes, a Hungarian painter closely associated with his fellow countryman László Moholy-Nagy, the Bauhaus master, asserted in his 1944 Language of Vision that

the orderly repetition or regular alternation of optical similarities or equalities dictates the rhythm of the plastic organization. In recognizing such order one learns when the next eye action is due and what particular neuromuscular adjustment will be necessary to grasp the next unit. To conserve the attentive energies of vision, therefore, the picture surface must have a temporal structure of organization—it must be rhythmically articulated in a way that corresponds, for the eye, to the rhythm of any work process.2

Kepes may have had visual media in mind when he wrote on “the picture surface,” but the observation holds for architecture as well. For the prolific Danish urbanist and critic Steen Eiler Rasmussen, serial repetition offered a quintessential means by which to convey orderliness in design. “The simplest method,” wrote Rasmussen in his 1959 guide Experiencing Architecture, “for both the architect and the artisans, is the absolutely regular repetition of the same elements, for example solid, void, solid, void, just as you count one, two, one, two. It is a rhythm everyone can grasp.”3 Here again, as with Kepes, repeated components operate by establishing a kind of rhythm of intuition, which then structures all subsequent experience. Each passage highlights the peculiar double aspect of repetition in architecture: it is simultaneously an objective property of the built work—perceptible to both inhabitants and passersby—and a subjective approach to design.

Repetition as “rhythm” suggests a musical analogy. In architecture, however, rhythm is realized in space. Pierre von Meiss, a Swiss architecture theorist of some renown, made this connection explicit in his popular Elements of Architecture: From Form to Place (1986). Like Kepes, von Meiss emphasized repetition’s role in the economy of vision by explaining how “the eye tends to group together things of the same type. Even when the elements taken in pairs are somewhat different,” he continues, “we find that the structural resemblance dominates these differences. Repetition in any form of rhythm—as much in music as in architecture—is an extremely simple principle of composition which tends to give a sense of coherence.”4 Musical rhythm, however, already implies a regular cadence or meter indexing its temporality: in short, its tempo. After a certain amount of time has passed in a piece of music, either a change occurs or an element repeats. While the constancy of this interval might seem to indicate stasis (since it determines a set duration), the unfolding of rhythm over time lends it a dynamic character. Is there anything in architecture that offers an equivalent?

Static and Dynamic Repetition in Architecture

Repetition in architecture could perhaps be divided along lines similar to those found in music: into a purely spatial, static form and a quasi-temporal, dynamic form. The latter, which roughly approximates modern notions of architectural rhythm, may be better understood by contrasting it with the former, which corresponds to the older ideal of architectural harmony (Vitruvian eurhythmia).5 Harmony as a principle of construction is typically thought to consist in the balance achieved between a building’s length, width, and height.6 Here, eurhythmia is essentially a homeostatic concept; its proper domain remains circumscribed within these three dimensions of space, excluding the dimension of time. Its aim, classically speaking, is to bring about a state of “repose,” often in conjunction with symmetry and proportion. Or so it was from architecture’s earliest known origins, down through Semper and Viollet-le-Duc and up to the cusp of the fin de siècle.7 With Berlage, one can even see this course extending into the opening decades of the twentieth century,8 as has been pointed out by Reyner Banham.9 As the French Marxist and sociologist Henri Lefebvre once put it, late in life, eurhythmia aspires to an almost glacial timelessness, seeking to sustain “metastable equilibrium” between spatial bodies.10

Repetition therefore assumes a more purely spatial form whenever it is used to express a relation of symmetry or equilibrium. One side matches the other, in an immediately graspable fashion. Nicolas Le Camus de Mézières, one of France’s leading architects during the Enlightenment, stressed precisely this point in his 1780 text The Genius of Architecture, or the Analogy of that Art with Our Sensations: “Symmetry, or the use of repeated and balanced forms, is essential. Where glass appears on the one side, there must be a glass on the other, of the same dimensions and in a frame of the same shape.”11 Cut down the middle, each half is inversely proportionate to that from which it was divided. Hermann Weyl argued that a similar principle of static spatial repetition informed Attic and Ionian ceramics in ancient Greece, albeit unconsciously, from the seventh century BCE onward. In his seminal treatise on Symmetry (1952), Weyl demonstrated the mathematical underpinnings of a number of vases dating from the aptly named “geometric” period.12 The repetition exhibited in these pieces, he held, was quite separate from what he had discussed as “one-dimensional time repetition” a few pages earlier.13

Repetition’s quasi-temporal form enters in somewhat later, alongside the development of a “new space conception,” namely space-time, which helped pave the way for modern design.14 Sigfried Giedion located the decisive moment of this breakthrough at sometime around the turn of the century. It occurred either in 1909, with the publication of Marinetti’s Futurist Manifesto (fresh on the heels of Minkowski’s 1908 lecture on “Space and Time”),15 or in 1911, with the first of Guillaume Apollinaire’s famous essays on The Cubist Painters (not long after Einstein’s painstaking definition of simultaneity in his work on electrodynamics).16 Einstein’s objections to this dubious analogy between art and science are well-documented,17 but may be set aside for now. The root of Giedion’s error may be traced to his rather ham-fisted attempt to draw a parallel between coincidental shifts in their epistemic foundations, through which he mistook correlation for causation. Giedion is better served by his focus on the social and historic transformations that form the basis for transformations in the ideological superstructure of a given epoch—such as the Industrial Revolution, and all the cultural and political upheaval that followed in its wake.18

Repetition manifests itself differently in its dynamic form than in its static variant; time introduces a whole range of hitherto unimaginable possibilities into the field of architecture. Asymmetries, imbalances, and disequilibria may be temporarily displaced, awaiting resolution elsewhere. In the meantime, they are held at bay. The Soviet Constructivist and architectural theorist Moisei Ginzburg compared the dynamism of modern design to the pulsating rhythm of industrial machinery, which he felt epitomized the new way of life being formulated in the earlier half of the twentieth century.19] a picture of modernity that is extremely lucid and differentiated from the past.” Moisei Ginzburg, Style and Epoch, trans. Anatole Senkevitch (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. 1982), 80–81.] In his 1924 text Style and Epoch, he characterized the principal lesson to be learned from the machine as follows:

The machine … gives rise to a conception of entirely new and modern organisms possessing the distinctly expressed characteristics of movement—its tension and intensity, as well as its keenly expressed direction … The axis of movement generally occurs … beyond the machine itself. The question of symmetry in a machine is thus an altogether secondary one, not subordinated to the main compositional idea … It is possible and natural for the modern architect’s conceptions to yield a form that is asymmetrical or that, at best, has no more than a single axis of symmetry, which is subordinated to the main axis of movement and does not coincide with it.20

Ginzburg’s repeated use of organic metaphors in his description of machines at times seems to anticipate the effusive language later employed by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari in their jointly written Anti-Oedipus, from 1972.21 In both cases, an attempt is made to overcome the usual dichotomy of organism versus mechanism. This superficial resemblance is belied, however, by the thoroughgoing modernism of the former’s interpretation of history. Not only in Style and Epoch, but already his earlier work on Rhythm in Architecture from 1923, Ginzburg sought to decipher the principle that essentially unites the apparent multiplicity of historical forms. For him, the core feature underlying all past styles was nothing other than “rhythm.”22 What distinguished modern architecture from everything that had come before, he contended, was the dynamic quality of its rhythm. It was thus no accident that Ginzburg went on to describe the main body of Dom Narkomfin in Moscow—his undisputed masterpiece, co-designed with Ignatii Milinis in 1928—as “a ribbon of dwelling units in the shape of a long, uniform volume, with rhythmically repeating elements.”23

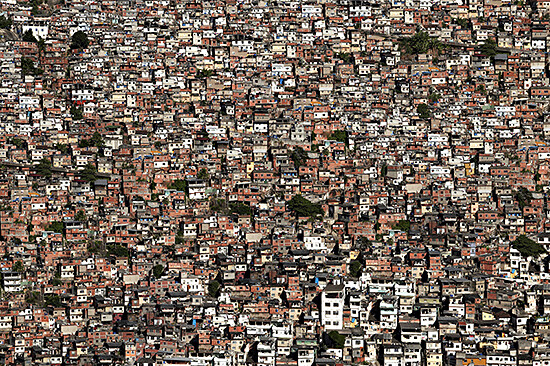

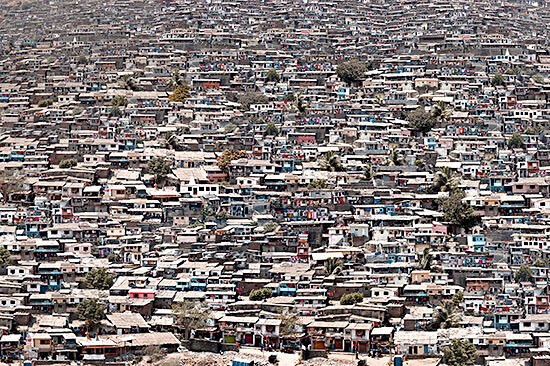

Repetition may be mobilized at the level of the city as well. Urban sites can on the whole be dynamically configured, of course, while still making use of repetitive parts; cities needn’t always be arranged according to a grid of rectilinear blocks or a radial agglomeration of concentric rings, both of which abide by fixed relationships of balance or symmetry. Such was the topic Giedion hoped to address in a remarkable article, today virtually unknown, on “Aesthetics and the Human Habitat” (1953), which he presented that year at CIAM 9 in Aix-en-Provence. Giedion insisted that, in addition to new plastic forms of composition, it would be necessary to cultivate new faculties of perception in step with these forms. Modernity, he maintained, “demands a new plastic sensibility: the development of a sense of spatial rhythms and a new faculty of perceiving the play of volumes in space.”24 From simple architectural units, then, a more complex urban fabric is composed. “We accept the use of repetition as an active factor in the creation of a plastic expression,” Giedion continued. “Each functional element should express itself by means of a differentiation of form and color which would serve to give both a diversity within the larger … residential sectors and, at the same time, a certain unity which would contribute a general rhythm throughout the city as a whole.”25 This contemporary urbanistic rhythm is strictly modern, moreover, which (as Giedion made clear) can be distinguished from traditional rhythms based on “equipoise.”26

Global Modernity and World History27

Repetition is thus reordered into different scales, from architecture up to urbanism down to design. Its particular appearance in any one of these realms is bound up with the universal logic of capitalist development, which it repeatedly embodies and refracts as materialized ideology.28 Lefebvre picked up on this specifically modern rhythm of daily life in the section of The Production of Space (1972) devoted to spatial architectonics, in which he first proposed the idea of a “rhythmanalysis.”29 In his posthumously published work on the subject, unfortunately left unfinished, he recorded: “No rhythm without repetition in time and in space, without reprises, without returns, in short without measure [mesure].”30 For Lefebvre, one major consequence of capitalism’s unique spatiotemporal framework was that its rhythm is both cyclical and linear—a cyclolinear motion.31 The lines that demarcate it from precapitalist rhythms are perhaps not drawn sharply enough in Lefebvre’s account, but this does not diminish the validity of his insights. More precisely, he fails to appreciate the globalization of space in the creation of the world alongside the modernization of time in the creation of history. Bourgeois society represents the dawn of “world history” in the emphatic sense, just as the emergence of industrial capitalism marks the beginning of its crisis.32] arises only when the owner of the means of production and subsistence finds the free worker available … This one historical precondition comprises a world’s history.” Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, vol. 1, trans. Ben Fowkes (New York: Penguin Books, 1972), 272.]

Repetition can be viewed from yet another vantage point that proves pertinent to questions of art and architecture. Besides rhythmic repetitions of predetermined patterns or motifs within a given spatial ensemble, there are likewise periodic repetitions of earlier gestures or conceits within a given temporal progression. This does not refer so much to the cataloguing and systematized reuse of past styles in nineteenth-century architectural historicism as it does to the neo-avant-garde propensity in the 1950s–1970s to return to themes originally established by the classical avant-garde in the 1910s–1930s. Hal Foster provided what is probably still the best examination of this tendency in his 1997 text Return of the Real, where he set the pervasiveness of artistic and architectural “returns” in these decades into the broader context of concurrent “returns” in Marxism and psychoanalysis happening around roughly the same time. “In postwar art to pose the question of repetition is to pose the question of the neo-avantgarde, a loose grouping of North American and Western European artists of the 1950s and 1960s,” Foster claimed, “who reprised such avant-garde devices of the 1910s and 1920s as collage and assemblage, the readymade and the grid, monochrome painting and constructed sculpture.”33 Like Louis Althusser and Jacques Lacan, who undertook rereadings of canonical texts by Karl Marx and Sigmund Freud in order to counter the alleged “vulgarizations” of their thought by the traditions that stemmed from them, members of the neo-avant-garde during this period, including Dan Flavin and Zaha Hadid, revisited artworks by Vladimir Tatlin and Kazimir Malevich.34 Such returns were supposed to recover the revolutionary impetus that originally belonged to Marxian socialism and Freudian psychoanalysis, as well as Constructivist and Suprematist strains of modernism. Unlike Peter Bürger, for whom the neo-avant-garde’s repetition of the classical avant-garde’s revolt against tradition was farcical,35 Foster saw this exercise as a self-aware intervention into historical practices whose once-radical novelty had calcified into routine.36 He recommended taking a page from psychoanalysis in order to understand this compulsive drive to repeat.

The repetition-compulsion “endeavors to make a trauma real by living through it once more”—this was how Freud construed it, at least.37 Another pithy formulation of his: “Repetition is the re-experiencing of something identical.”38 But what exactly does this uncontrollable urge to repeat signify? Of what is it symptomatic? For Foster, the neo-avant-garde’s desire to return to its own origins—its felt need to relive the primordial act of rebellion—pointed to unfinished business left by the historical avant-garde, some desiderata that had gone unresolved. “If the historical avant-garde was repressed institutionally, it was repeated in the neo-avant-garde rather than, in the Freudian distinction, recollected, its contradictions worked through,” Foster wrote. “The avant-garde was made to appear historical before it was allowed to become effective,” he continued, “that is, before its aesthetic-political ramifications could be sorted out, let alone elaborated.”39 Divorced from the material conditions that had engendered the avant-garde project to begin with, the inadequacy of this first repetition necessitated a second.

Repetition and difference have been closely linked since Deleuze’s Difference and Repetition, if not before its publication in 1966. Today the association is practically automatic. Foster drew attention to this fact in his article on “The Crux of Minimalism” in Return of the Real,40 back when he still held out hope for its subversive potential.41 Even Lefebvre fell under its sway toward the end of his life, whatever reservations he may have held along the way.42 Deleuzean difference, to explain, is itself generated through the process of repetition: “Difference inhabits repetition,” or rather, “Difference lies between two repetitions.”43 Something must exist in order to differentiate the copy from the original, the repetition from that which is repeated. If this does not occur in the object, then it must occur in the subject perceiving it. Older notions of repetition as an “eternal return” of the selfsame are thereby undermined. The metaphysics of this operation, Deleuze’s back-and-forth between ontology and epistemology, are only interesting insofar as they inspired a generation of architects who looked to theory for guidance. Aside from this, his entire undertaking in Difference and Repetition feels strangely anachronistic today—unable to comprehend the conditions of its own exigency.

Repetition as a facet of history figures briefly into Deleuze’s inquiry; a few paragraphs of the text are spent reflecting on Marx’s famous line about how world-historical personages and facts happen twice, “first as tragedy, then as farce.”44 Indeed, these sentences arguably comprise the best section of the book, and are sadly occluded by its otherwise metaphysical emphasis. However, Deleuze clearly benefited from the exegesis of a skilled interlocutor— Harold Rosenberg, to be exact, with his treatment of the issue in his 1959 book The Tradition of the New.45 Rosenberg convincingly showed that Marx did not reject every effort to repeat the past out of hand. This is doubly true in light of his deep admiration for the 1789 French Revolution, which by his own testimony donned the garb of the Roman Republic. Tragedy and farce in history would both seem to involve repetition, then; the difference is rather that the latter is twice removed from its point of origin, as an attempt to repeat what was already an attempted repetition.46 Either way, Rosenberg knew well enough that changed circumstances would inevitably intervene: “Through the effect of time … the repetition of the past becomes a repetition in appearance only; the permanent effectuality of change permits no true repetition.”47

Repetition induces a certain anxiety of influence in architects, modern and contemporary alike. A distinct horror is attached to the idea that one is merely repeating past formulae and techniques, that his or her projects are little more than rote exercises demonstrating competence. This probably would not have bothered premodern builders in the least, as nothing could be thought more noble than the mastery of time-honored principles.48 In modern times, by contrast, derivative works are marked by the stigma of “unoriginality.” Modernists bristled at the suggestion that the architect’s task was to simply emulate his predecessors, or even recombine their styles in novel ways. All the same, they accepted repeatability—in the form of standardization—as a maxim in their designs. Only by designing repeatable models could their buildings be mass-produced, in contradistinction to all hitherto existing architecture. Walter Gropius, legendary founder of the Bauhaus, thus asserted in his 1925 book The New Architecture that “the repetition of standardized parts, and the use of identical materials in different buildings, will have the same sort of coordinating and sobering effect on the aspect of our towns as uniformity of type in modern attire has in social life.”49 For modern architects, the repeatability of new forms was affirmed just as the repetition of old forms was denied.

The Old in the New

Repetition stirs a different kind of discomfort in contemporary architects. To them, part of what made modern architecture so problematic was its repetitive (if not utterly generic) appearance. Searching for a way out, Charles Jencks turned to “adhocism”50; Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown learned from the Las Vegas Strip51; and Paolo Portoghesi hybridized elements of modernism with classicism.52 Besides the postmodernists, however, another constellation of architects hoped to exploit new digital possibilities in departing from the modern movement. “Parametricism looks for continuous programmatic variations rather than the repetition of strict function types,” writes Patrik Schumacher in The Autopoiesis of Architecture. “Instead of juxtaposing discrete functional domains this style prefers to offer all the in-between iterations that might be conceived between two function types.”53 Schumacher, chief theorist of parametricism in architecture and prominent partner of Zaha Hadid, leans heavily on the philosophy of Deleuze, but clearly favors differentiation over repetition. He offers the following advice: “Instead of working with rigid forms, set up all architectural elements as parametrically malleable; instead of repeating elements, set up systems that continuously differentiate its elements.”54 Oddly, both he and Hadid recapitulate some of the expressionist undercurrents of modern architecture while forsaking its functionalist mainstream. Geometric orthogonality is abandoned for organic continuity. It chases after smooth, undulating surfaces.55

Repetition reaches toward its putative other, nonrepetition, in parametricism’s reversion to Futurist and Expressionist precursors. The modus operandi of Hadid, Schumacher, and others is to resuscitate “neglected” or “overlooked” strains of modern architecture, whose potential for radical innovation was cut short, by repeating their forms with the help of advanced CATIA (Computer-Aided Three-Dimensional Interactive Application) technologies.56 Zaha’s recent shift away from Suprematist and Constructivist precedents toward Futurist and Expressionist ones is all part of a singular progression/regression.57 But these revivals do nothing to reanimate the turbulent social conditions that gave rise to these architectural currents in the first place, which still grant them their revolutionary aura. Even Foster, who previously defended the neo-avant-garde from such hasty dismissals, has lately found himself agreeing with Bürger on this score. He writes: “In the end … Hadid might not escape the accusation that Bürger made long ago against the neo-avant-garde project: to fail in its critique, as the historical avant-garde did, is one thing, but to repeat such a failure—more, to recoup this critique as style—is to risk farce.”58 Moreover, the sheer ubiquity of these non-orthogonal, unrepeatable gems causes them to pass dialectically into their opposite. As the architecture critic Douglas Murphy has noted, in biting remarks directed at Hadid, Schumacher, and the British starchitect Norman Foster, “Difference is becoming standardized; the unique is becoming generic.”59

Repetition is essential to architecture in one final respect—to the extent that it overlaps with the sociological category of habitus. Georges Teyssot, the onetime protégé of Manfredo Tafuri, has dissected this relationship in the titular article to his Topology of Everyday Constellations (2013). Examining the tangled web of historical and etymological associations that lead from habitation to habituation, along with the theoreticians and philosophers who’ve dealt with it, Teyssot determines that

the process of repetition … orders our lives. The … repetition of need shapes time, but need is not properly understood in relation to a negative state, such as lack. Repetition is essentially inscribed in need, and this fact gives form to various aspects of duration in a person’s life: rhythms (of the body), reserves (of energy), reaction times, intertwinings (of relationships). It is tempting to extend this notion of habit to the house itself, conceived as a receptacle of practices, routines, and customs.60

Teyssot moves seamlessly between different disciplinary boundaries, from phenomenology to anthropology and beyond, delineating the structures of everyday life. Working his way up from the micro to the macro, in the manner of Raoul Vaneigem and Michel de Certeau, he avers that “the plurality of micro-events, the series of individual and social habits, repeated over the course of time, seems to hammer spaces with tiny, repeated blows, molding or forging, as it were, an ‘environment’ … of everyday life.”61 Over and above this gradient texture of cumulative, quotidian interchange lurks a more sinister figure of accumulation-by-repetition, however: the ongoing reproduction of the capitalist totality. “In the capitalist production of commodities,” Teyssot acknowledges, “the new and the novel stimulate demand by reintroducing meaning. At the same time, the process of repetition, organized for commodity production, imposes ‘the eternal return of the same’ (immer gleich).”62

Repetition in architecture today, as in every other cultural sphere, attests to the historical impasse at which society has lingered for almost a century. Architects find themselves forced to recycle, reorder, and repeat novelties of the past in order to remain “cutting-edge” in the present. No longer does the steady march of technological progress provide a path for architecture to follow. Teyssot only glancingly grasps what Tafuri would have deemed decisive—the extraordinary dynamism of capitalist society masks a certain static remainder, one which cannot be reduced to surviving traditions, communal ties, or simple “pattern maintenance.”63

As Theodor Adorno put it in his 1942 essay “Reflections on Class Theory,” what appears today as ever-new under the conditions of late capitalism is in fact merely “the old in distress.”64 Lefebvre made an almost identical point three decades later in The Survival of Capitalism (1973), wherein he noticed that “the concept and theory of reproduction brings out one of the most prominent but least noticed features of ‘modernity,’ the prevalence of repetition in all spheres. This poor little world … is condemned not only to reproduce in order to reproduce itself, together with its constitutive relations, but also to present what is repeated as new, and as all the more new (neo) the more archaic it actually is.”65 It matters little whether the forms of the past that are marshaled in the service of the present are repetitive or nonrepetitive. Until the capitalist social formation is finally overcome, they can only be the old repackaged as new.

Clark Fagot and Harold Pashler, “Repetition Blindness: Perception or Memory Failure?” Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance vol. 21, no 2. (April 1995): 275–292.

György Kepes, Language of Vision (Mineola, NY: Dover, 1995), 53.

Steen Eiler Rasmussen, Experiencing Architecture (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1964), 129.

Pierre von Meiss, Elements of Architecture: From Form to Place, trans. Pierre von Meiss (New York: Routledge, 1990), 32.

Vitruvius, On Architecture, trans. Richard Schonfield (New York: Penguin Books, 2009), 13.

“Harmony consists of a beautiful appearance and harmonious effect … achieved when the height of the elements of a building are suitable to their breadth, and their breadth to their length, and in a word, when all the elements match its modular [symmetrical] system.” Ibid., 14.

Semper championed “repose and harmony in colors (as well as in spatial combinations).” Gottfried Semper, Style in the Technical and Tectonic Arts, or, Practical Aesthetics, trans. Harry Francis Mallgrave and Michael Robinson (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2004), 135.

Berlage quotes the historian Johannes H. Leliman’s lectures on Greek building: “Its exalted repose finds form in stone; all proportions of dimension and mass are well balanced … Perfect harmony makes all parts resonate in powerful chords.” Hendrik Petrus Berlage, “Some Reflections on Classical Architecture” [1908], trans. Wim de Wit, Thoughts on Style: 1886–1909 (Santa Monica: Getty Center Publications, 1996), 270.

“The aim of all artistic creation, in [Berlage’s mind], was the achievement of repose, and thus of style, the ultimate aesthetic quality.” Reyner Banham, Theory and Design in the First Machine Age (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1980), 143.

“Harmony sometimes (often) exists: eurhythmia. The eu-rhythmic body, composed of diverse rhythms … keeps them in metastable equilibrium.” Henri Lefebvre, Elements of Rhythmanalysis: An Introduction to the Understanding of Rhythms, in Rhythmanalysis: Space, Time and Everyday Life, trans. Stuart Elden and Gerald Moore (New York: Continuum, 2004), 20.

Nicolas Le Camus de Mézières, The Genius of Architecture, or the Analogy of that Art with Our Sensations, trans. David Britt (Santa Monica: Getty Center Publications, 1992), 89–90.

“We return to symmetry in space. Take a band ornament where the individual section repeated again and again is of length a and sling it around a circular cylinder, the circumference of which is an integral multiple of a, for instance 25a. You then obtain a pattern which is carried over into itself through the rotation around the cylinder axis by α = 360°/25 and its repetitions. The twenty-fifth iteration is the rotation by 360°, or the identity. We thus get a finite group of rotations of order 25, i.e. one consisting of 25 operations. The cylinder may be replaced by any surface of cylindrical symmetry.” Hermann Weyl, Symmetry (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1952), 53–54.

Ibid., 51.

Sigfried Giedion, Space, Time, and Architecture: The Growth of a New Tradition (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press, 1982), 430.

Ibid., 443.

Ibid., 436.

Wolf von Eckardt, Eric Mendelsohn (New York: George Braziller, Inc., 1960), 14.

Giedion, Space, Time, and Architecture, 165–289.

“Modern industrial plants condense within themselves … all the most characteristic and potential features of the new life. [Here is

Ibid., 92.

Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Robert Hurley, Mark Seem, Helen R. Lane (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1983).

“The history of styles, as it has been understood until recent times, is simply the history of the evolution of architectural form. Compositional methods … have remained in the background. Nevertheless, by discerning the peculiarity of compositional rules, one also fully understands style … Together with the history of architectural forms, it is possible to establish a parallel history of compositional methods, which above all analyzes the driving force behind such methods: rhythm, in all its diverse manifestations.” Moisei Ginzburg, Ritm v arkhitekture (Moscow: 1923), 71. A translation of the Russian: “История стилей, как она понималась до последнего времени, —есть лишь история эволюции архитектурной формы. Композиционные методы…оставались на заднем плане. Однако и здесь разгадать своеобразие этих композиционных законов значит понять вполне стиль … Наряду с историей архитектурных форм возможна и параллельная история композиционных методов, анализирующая в первую очередь двигательную силу этих методов: ритм, во всем разнообразии его проявления.”

A translation of the Russian: “Лента жилых ячеек … в виде длинного однообразного объема с ритмически повторяющимися элементами.”

Sigfried Giedion, “Aesthetics and the Human Habitat,” in Architecture and Me: The Diary of a Development (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1958), 93.

Ibid., 95.

Giedion flirts with atavism here, but restrains himself: “The attitude of contemporary architecture toward other civilizations is a humble one … Often shantytowns contain within themselves vestiges of the last balanced civilization—the last civilization in which man was in equipoise.” Ibid., 96

The phrase “global modernity” is a coinage of the Turkish historian Arif Dirlik, but the sense intended here follows more closely Zygmunt Bauman’s notion of a “liquid modernity” founded upon fluid networks of global exchange (which Dirlik draws upon himself). See Zygmunt Bauman, Liquid Modernity (Malden, MA: Polity Press, 2000), 185–198.

Manfredo Tafuri, Architecture and Utopia: Design and Capitalist Development, trans. Barbara Luigia La Penta (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1976), 60–61.

Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space, trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith (Cambridge, MA: Basil Blackwell, Inc., 1991), 205–207.

Lefebvre, Rhythmanalysis, 6.

“Time and space, the cyclical and the linear, exert a reciprocal action: … everything is cyclical repetition through linear repetitions. A dialectical relation (unity in opposition) thus acquires meaning and import … One reaches, by this road as by others, the depths of the dialectic.” Ibid., 8.

“[Bourgeois society

Hal Foster, “Who’s Afraid of the Neo-Avant-Garde?,” in The Return of the Real: The Avant-Garde at the Turn of the Century (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1997), 1.

Ibid., 2–5.

“The Neo-avant-garde, which stages for a second time the avant-gardiste break with tradition, becomes a manifestation that is void of sense.” Peter Bürger, Theory of the Avant-Garde, trans. Michael Shaw (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984), 61.

Foster, “Who’s Afraid of the Neo-Avant-Garde?,” 8, 10, 13–14.

Sigmund Freud, “Repetition-Compulsion,” trans. Theodore Reik, Dictionary of Psychoanalysis (New York: Praeger, 1966), 157.

Sigmund Freud, Beyond the Pleasure Principle, trans. James Strachey and Anna Freud, in Complete Psychological Works, Volume 18: 1920–1922 (London: Vintage Books, 2001), 36.

Foster, “Who’s Afraid of the Neo-Avant-Garde?,” 28.

Hal Foster, “The Crux of Minimalism,” in The Return of the Real, 66–68.

Ibid., 63.

“There is no identical absolute repetition, indefinitely. Whence the relation between repetition and difference. When it concerns the everyday, rites, ceremonies, fêtes, rules and laws, there is always something new and unforeseen that introduces itself into the repetitive: difference.” Lefebvre, Rhythmanalysis, 6. See also ibid., 9–10, 15, 26, 32, 43, 90.

Gilles Deleuze, Difference and Repetition, trans. Paul Patton (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994), 76.

Karl Marx, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, trans. Saul K. Padover, Collected Works, Volume 11: August 1851–March 1853 (New York: International Publishers, 1979), 103.

“Karl Marx’s theory of historical repetition, as it appears notably in The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, turns on the following principle which does not seem to have been sufficiently understood by historians: historical repetition is neither a matter of analogy nor a concept produced by the reflection of historians, but above all a condition of historical action itself. Harold Rosenberg illuminates this point in some fine pages: historical actors or agents can create only on condition that they identify themselves with figures from the past.” Deleuze, Difference and Repetition, 91.

“The historical relativism of the heroic is emphasized in Marx’s contrast between the repetition of tragedy and the repetition of farce, which he defines as the repetition of a repetition.” Harold Rosenberg, The Tradition of the New (New York: Da Capo Press, 1994), 161.

Ibid., 160–161.

“Conceptually the central problem for the latecomer necessarily is repetition, for repetition dialectically raised to re-creation is the ephebe’s road of excess, leading away from the horror of finding himself to be only a copy or a replica.” Harold Bloom, The Anxiety of Influence: A Theory of Poetry (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 80.

Walter Gropius, The New Architecture and the Bauhaus, trans. P. Morton Shand (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1965), 40.

Charles Jencks and Nathan Silver, Adhocism: The Case for Improvisation (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013).

Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown, Learning from Las Vegas (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1982).

Paolo Portoghesi, Postmodern, or the Architecture of Post-Industrial Society, trans. Ellen Shapiro (New York: Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., 1983).

Patrik Schumacher, The Autopoiesis of Architecture, Volume 1: A New Framework for Architecture (Hoboken, NJ: Jon Wiley & Sons, 2011), 259.

Ibid., 297.

Ibid., 118, 311–312, 332, 335, 353, 407.

Hal Foster, Design and Crime (And Other Diatribes) (New York: Verso Books, 2003), 35–37.

Hal Foster, The Art-Architecture Complex (New York: Verso Books, 2011), 82–83.

Ibid., 85.

Douglas Murphy, The Architecture of Failure (London: Zer0 Books, 2011), 136.

Georges Teyssot, The Topology of Everyday Constellations, trans. Pierre Bouvier and Julie Rose (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013), 17.

Ibid., 23.

Ibid., 18.

Ibid., 12–13.

“The new does not add itself to the old but remains the old in distress.” Theodor Adorno, “Reflections on Class Theory,” in Can One Live after Auschwitz? A Philosophical Reader, ed. Rolf Tiedmann, trans. Rodney Livingstone (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2003), 95.

Henri Lefebvre, The Survival of Capitalism: The Reproduction of the Relations of Production, trans. Frank Bryant (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1976), 32.

All photographs are copyright Marcus Lyon and appear courtesy of the artist, unless otherwise noted.