Colors of Intervention

On January 11, 2013, the French military launched Opération Serval,1 an attempt to assume command in Mali, France’s former colony. Using fighter jets and ground troops, France intervened on the side of the Malian armed forces to defend the country against a litany of militias advancing from the north: the Islamic Toureg fighters of Ansar Dine (Defenders of the Faith), the Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa (Mujao), the Salafist group Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), Ag Cherif’s secular Toureg alliance known as the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA), as well as free-floating drug gangs. The stated goal was to liberate the occupied cities and areas and to protect the estimated six thousand foreigners in Mali, most of whom were French-Malian dual citizens.2

The scene the French soldiers encountered on the streets of Mali when they marched in days later could hardly have been predicted. The elite troops of the erstwhile colonial power, from which Mali won independence in 1960 (the so-called Year of Africa) were greeted with effusive cheering and a demonstrative display of France’s national symbol, the Tricolour. Only a year prior, France was the target of sharp criticism from Mali, which at the time was experiencing a political and humanitarian crisis. The complaints focused not so much on France’s shameful historical role, but rather on the fact that the French had neglected to secure peace and order in their African sphere of influence (Françafrique) after their 2011 intervention in Libya—one of the causes of Mali’s crisis. But now the French and Malian flags hung in the streets side-by-side in intimate unity, as if the two nations’ friendship was the most natural thing in the world. Foreign correspondents reported on flag shortages in Bamako and Timbuktu. The photographs they dispatched showed streets brimming with flags: Malians who had strapped the Tricolour to their car antennas and motorbikes, Malian soldiers wearing the flag as a turban, and Malian civilians who had dressed themselves in flags. Asked for his opinion on the pictures of flag-waving Malians, Senegalese author and publisher Boubacar Boris Diop answered that, contrary to all reports, the pictures were staged propaganda. If they did suggest “an immense relief,” as characterized by one reporter at the time, this is precisely what made them disturbing, because it demonstrated how fully the population had been let down by its own country’s political class.

This temporary reoccupation of Mali constituted an act of military and political reterritorialization. The West African country had to be saved from territorial and political ruin by France’s intervention. But the flagrant reversal of Mali’s independence, under the premise of protecting its national sovereignty, caused the most diverse political camps, both within and outside of the country, to speak out against recolonization.3 The display of the French flag during the military intervention was itself an intervention into today’s (local and global) image space. As an abstraction of national and imperial identity and power, the flag organizes the field of the visible, communicating ideologies, ideas, and feelings in an often contradictory manner.

The Flag—A Medium

According to ethnologist Raymond Firth, the national flag isn’t only “a highly condensed focus of sentiment,” but also a deeply heterological symbol. It is open to contradictory interpretations and uses, and can even be used against the nation it represents—if only because “the sentiment component” is essentially uncontrollable. The symbolic power of the flag is obvious, and thus it is necessary to demonstrate its ambiguity. To what extent is a flag not only a symbol, but also a medium? Flags exist in different manifestations and materials, from the sewn flag on a mast to the GIF file. In essence, they are artificial, manufactured objects. Sewn or printed, their symbolic effect is a result both of antecedent production—from graphic development to the sewing machine—and formal and informal use. The hoisting or waving of the flag, but also its burning and tearing, are elements of a complex performativity grounded in history. The flag serves as a vehicle for political-identical argumentation; but it should also be considered in its materiality—as hardware.

Viewed this way, the flag borders on what media theory defines as a “medium”; at the very least, it merits media-scientific reflection. It’s important, at the same time, to consider that flags never occur in isolation. Rather, they are always (more or less firmly) integrated into material, social, urban, and technological environments and arrangements. In these contexts, flags fulfill not only a heterological function, but also a heterotopic function, in the Foucauldian sense. That is, they mark places and actions as “counter-placed,” ritualized, or extraterritorial. Combined with mediums like photography—one of the main focuses of this piece—the flag’s heterological-heterotopic aspects raise the question of its medial efficiency.

The Tricolour Behind the Front

During the French intervention, Canadian photojournalist Joe Penney—who has been reporting from Mali for Reuters since the 2012 military coup—became a diligent documenter of flag motifs.4 He took an unusual approach to capturing the Malian jubilations. On one of the days that the media wasn’t allowed near the front, Penney visited a rural area, where he shot a series of photos of Yacouba Konate, a 56-year-old man, wearing a rather ornate French flag—featuring the Gallic rooster and several inscriptions of the word “France”—as a shawl .5 In these pictures, Konate drapes himself in the style of soccer fans, or as if the flag were a robe indicative of a particular social position. This flag is not swaying or fluttering on a flagpole. Instead, it is a strangely tranquil, fixed symbol—a reappropriated textile stretched and moved by the man’s body, developing its own dignity.

This charged cloth, with its elaborate motifs—likely produced by one of the Chinese companies currently dominating the world flag market—is placed as an image-text-object in pronounced color contrast with its surroundings: a landscape marked by the brown tones of the Savannah, the yellow of a straw wall. Yacouba Konate poses before it all, looking confidently into the camera.

Penney’s visual rhetoric thus intends to highlight the sudden introduction of foreign colors—and accordingly, the intervention of a symbolic power, or the powerful symbolism that is analogous to the intervention of French troops—which Yacouba Konate immediately appropriates and incorporates.

Offering something of a contrast to Konate, who was three years old when the French colonial period ended, Penney also asked a ten-year-old Malian boy to pose for him, in a shop with light green walls.

In his left hand, he holds a piece of bread; in his propped-up right hand, he holds a French Tricolour tied to a stick (homemade by him or someone else). The picture was a huge success in newsrooms around the world; when Reuters offered it up for sale on January 29, 2013, countless newspapers picked it up. The photo of a child offers a world audience, which is culturally/geographically remote and largely uninformed, a different kind of access to the conflict in Mali—an easier access. Its emotional impact is immediate. The shining green of the walls becomes a dramatic backdrop for the improvised flag, framing its three colors.

This series, like the pictures of Yacouba Konate, is missing many of the characteristics usually found in photographs of flag-bearers. And as in the Konate series, a static, even statuary quality prevails. The child leans heavily, his back on a wooden block marked by innumerable blows from a butcher’s knife. He calmly holds the stick with the three interwoven patches of flag, which itself is presented in an unostentatious manner. Rather than waving it, the boy holds the flag matter-of-factly, as a natural utensil—a prosthetic. His gaze meets the lens of the camera with curious openness—or at least without any sign of feeling intimidated—while his body appears to be pressed into the wooden block, pushed back either by the photographer’s presence or a heavy apparatus. This is not the (stereo)typical photojournalistic formula we know so well in the West: the African child suffering from lack of food and civilization. Something else is happening—has happened—here.

Recalling the ambiguity that, according to John Berger and Jean Mohr, is constitutive of all photography—a discontinuous cutout from a stream of events6—one gauges how difficult it is to adequately interpret and classify this image. It is even more difficult (and ultimately open-ended) to speculate about the child’s emotional state. If anything, it is more appropriate to speculate about affects, and about how the presence of the flag structures the semiotic situation of the scene.

The precarious state of the flag in Penney’s photo, its obvious constructedness, its makeshift nature, seems to conflict with its usual function: symbolizing the Grande Nation.The Tricolour is presented incorrectly, contrary to flag protocol. Usually, the French flag starts with the blue field on the left by the (imaginary) flagpole, the white in the middle, and the red to its right. The flag in Penney’s photo isn’t only tilted vertically by 90 degrees; it is also shown the wrong way around. But the picture worked for photo editors, who were looking for an image that captured the situation after the French intervention in a consistent, atmospheric, and perhaps unexpected manner. The caption underneath a drastically cut version of the photo on the front page of the Berliner Zeitung (January 31, 2013) claimed that the boy welcomed the French troops “happily.” The daily news media are keen on disambiguating the polysemy of images. The reductive combination of Tricolour and African child seems to permit no other conclusion: the boy is celebrating the intervention.

Signifier and Signified of Colonialism

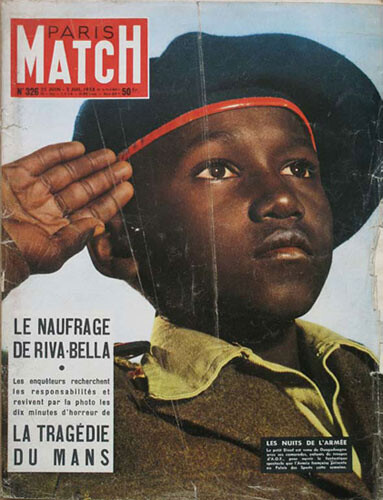

It now seems appropriate to reference a famous passage from Roland Barthes’s 1957 Mythologies. In a short, anticolonial section in the systemic part of the book, the semiologist discusses the iconic cover photo of the June 26, 1955 issue of Paris Match. It is a close-up of a young African cadet in uniform, who, according to Barthes, “is performing the military salute, his eyes raised and probably directed toward a fold in the Tricolour.”7 Barthes distinguishes between the “sense of the picture,” described above, and its meaning, which is

that France is a grand empire, that its sons, regardless of their skin color, serve loyally under its flag, and that that there is no better retort to the opponents of so-called colonialism than the eagerness with which this black man serves his alleged oppressors.8

Barthes translates this reading into the semiological distinction between the signifier (“a black soldier performs the French military salute”) and the signified (an “intentionally constructed mixture of Frenchness and soldiery”), which expresses itself in the “presence of the signified by means of the signifier.”9 In the mythical-ideological deployment of the picture, the soldier’s apparent act of gazing at the flag inevitably becomes legible as evidence of his loyalty and devotion to the French empire.

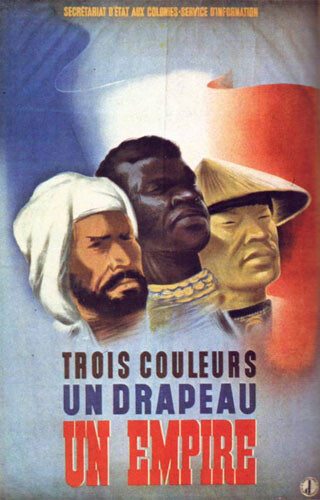

In a caption to the cover photo, the soldier is identified as “little Diouf,” but his full name is Diouf Birane. He has travelled from Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso today) to Paris with his comrades, the child cadets of the Afrique Occidentale Française (AOF). Along with four thousand other participants, they have assembled in the Palais des Sports for the so-called “nuits de l’armée,” a military parade (which, with its many circus and operetta-like elements, was essentially a colonial exhibition).10 The Paris Match cover photo is best located in the tradition of colonial propaganda. This form was exemplified most memorably by a notorious poster put out in 1940 by the Service d’information pour le Secretariat d’Etat aux Colonies of the Vichy government, which featured the slogan “three colors, one flag, one empire.” Three racist archetypes are shown together (a North African, a sub-Saharan, and an East Asian member of the French colonial forces), their heads all turned toward a symbolic manifestation of the nation: the Tricolour. It flies in the wind behind their backs, surrounding and capturing them. The Tricolour is visually conflated with the representatives of the colonized and recruited populations. Their heads seem to perforate the gaseous tricolor atmosphere, constructing a unity that suggests an affective attachment to the project of colonialism, anchored in the sight of the flag (or due to a projection of the flag as a supposedly natural environment).11

Residual National Symbolism

Joe Penney’s picture of the child in Douentza emerged almost sixty-three years after the photograph of Diouf Birane on the cover of Paris Match. The place and the function of the flag have changed in many ways. The child in Penney’s photo, apparently a bit younger than Diouf Birane in 1955, doesn’t lift his gaze toward a military presentation of a real or imagined Tricolour, but instead directs it away from the flag in his hand and toward the camera. As a resident of a country that is to be freed from Islamist rebels and their reign of terror by French troops, he has a different relationship to France than the colonized subject Diouf Birane, who was exploited directly for France’s colonial project. The signified, in Barthes’s words, is no longer the “mixture of Frenchness and soldiery” of the late colonial era, but the postcolonial, globalized world order, wherein France has assumed a special role. It is a former colonial power and a current geopolitical and geoeconomic actor. Among other economic concerns, it doesn’t want to see regional instability encumber its uranium mining in neighboring Niger. France is thus acting in its own national interest, but also according to the power logic of the new empire of international capitalism, which holds onto national representation only when it benefits the economic interests of the regime.

The fact that this has little to do with a myth that abides by the protocols and etiquette required to manage national symbols, and much to do instead with an allusive memory of a possible and bygone function of national representation, becomes clear when one recognizes the improvised and needy quality of the supposedly “jubilant” reception of the French troops. Penney, the ambitious composer, conveys this point. In all its sluggish, homemade materiality and vulnerability, the Tricolour hangs off a stick, instead of being presented as a numinous phenomenon or as the object of a young cadet’s gaze. As such, it is anything but a triumphant symbol of victory. It is more of a relic, a pathetic remnant of the Grande Nation. Despite this, or precisely because it slightly contradicts our expectations, it remains attractive to the photojournalist on the lookout for unusual motifs.

The Totemism of the Flag

When the French colonial troops appeared in West Africa in the 1890s and announced their territorial and economic demands, they brought along the Tricolour. In 1894, French soldiers took the flag to cities like Timbuktu and Abomey as a symbol of triumph—the arrival of civilization. The flag helped the propagandists of the time (the picture journalists, with their drawing pencils) construct the myth of empire. While the white French soldiers wore white or blue and white, many of the “indigenous” members of the French military were dressed in Tricolour. The multiethnic tirailleurs sénégalais, for example, were equipped with a red fez, white harem pants, and a blue doublet. They were flag fabric, part of the symbolic staging of the empire.

Returning in January 2013, the French troops weren’t brandishing flags. Instead, they themselves were greeted from the roadside by the Tricolour, which had been selling like hot cakes in the days after the intervention. Waving France and Mali’s respective tricolor flags together was popular among Malians as well as foreign correspondents. What better way to emphasize the joint military campaign, the new brotherhood in arms, the postimperial commonality? On the streets of Timbuktu and Bamako, it emerged as a convenient, easily legible, almost universal symbol—ready-made for media dissemination and exploitation. This double-flagging was taken particularly far by one Malian, who found his way to Independence Square on February 2, 2013, in expectation of President Hollande’s arrival. Again, it was Joe Penney who photographed this figure in the crowd and spread his picture around the world via Reuters. The man in the photograph has painted his upper body—even his head—blue, white, and red. On his chest, he wears the inscription “Bienvenue le sauveur François Hollande.” As a skirt or pants—it isn’t clear which—he sports the Malian national colors: green, yellow, and red. In each hand, he holds one of the national flags. Even though this kind of body painting has long been a common practice in sports—particularly among football fans—it is jarring in light of colonial history, particularly the aforementioned stooping of “indigenous” soldiers in the Tricolour. (It harkens back to Jean Rouch’s 1956 film Les maitres fous, in which the natives literally embody the colors of their colonizers.12) This tricolored masquerade has a threatening, eerie quality—as if the picture of a body, seemingly transformed into a symbol of recolonization, is potentially contagious.

The emerging totemism of the flag here refers us back to the likely beginning of the anthropology and sociology of the flag, which can be found in Marcel Mauss and Émile Durkheim’s thoughts on primitive forms of classification from 1903, or in Durkheim’s 1912 “Elementary Forms of the Religious Life.” The latter interprets the totem as an emblem of group accord, a way for people to classify themselves as a group. Durkheim compares the totem with “clan flags,” the symbol that big families used to separate themselves from others, and which were symbols both of God and society.13 In certain studies of civil religion in modern states, particularly the United States, the flag is understood as a totem-emblem. As such, it permeates all areas of life, even adorning the bodies of the citizenry in the form of tattoos—while it is simultaneously cherished as a sacred object that must be protected from defilement and desecration by complex rituals and laws:

The definition of the holy as what is set apart, whole and complete, one and physically perfect, explains why there is horror in burning or cutting the flag, and danger in its being dismembered and rendered partial. A worn and tattered flag is ritually perilous and must be ceremonially burned so that nothing at all is left. The flag is treated both as a live being and as the sacred embodiment of a dead one. Horror at burning the flag is a ritual response to the prohibition against killing the totem.14

The religious-ritual use of the flag stands in close relation to its function in the military context. In German, a distinction is made between banners and flags. Traditionally, banners were custom-made from precious materials, painted, and embroidered to identify a particular military unit (until they were progressively standardized in the seventeenth century). Flags, by contrast, were exchangeable vehicles for iconography. According to these semantics, the material of the flag doesn’t play a decisive role; its main function is the visual communication of information over long distances. Only in the late eighteenth century, after the American and French revolutions—at the dawn of modern nation-building—did the flag become an indicator of nationality that adhered to certain rules in the international context (serving, for example, as a signpost of occupation). Its installation or raising announces the takeover of a territory or building; the modern cult surrounding the flag transfers the military unit’s sense of honor onto nations and political ideologies.15

Materiality of the Flag

But are the materiality and material value of the flag really irrelevant to its symbolic, identity-bestowing, affecting quality? As Émile Durkheim noted, though a flag may only be a printed piece of fabric, a sign without value, a soldier would still die to save it.16 The physical nature of the signifier would thus be irrelevant to the signified as well as to the sign itself. But to make this argument, one has to advance a semiotics that abstracts all vehicles (or mediums) and their respective materiality in favor of a term conveying purely visual information. Indeed, the materiality, the texture of a particular flag object, is vitally important to its meaning and use. At least in the representation of the flag’s use (the performance of the flag), particular circumstances, such as the decrepit or dignified appearance of the flag, can be charged with significant meaning—discursive meaning and, of at least equal importance, affective sense.

The patchy quality of the Tricolour in Penney’s photographs of Douentza follows a long tradition of depicting flags in an imperfect, unfinished, or worn out state. This type of image can be found in the iconography of battles and revolutions, where banners and flags are shown captured, defended, or in the possession of a victorious enemy. Flags are easily damaged and, for that reason, valuable. Particularly in the United States, the image of the torn and tattered Stars and Stripes has been a popular motif since at least the Civil War. A ritual routine is made of posing for the war photographer with the saved flag brought home from battle. Every stock photography agency has a tattered flag on offer.17

From the Child’s Flag to the Rainbow Flag

The story in Penney’s photographs of the flag-bearing child in Douentza is different, because that flag was not damaged by war or another catastrophe, but was an improvised expression of happiness and gratitude. And yet, the picture does demonstrate how much flags exist in material, semiotic hierarchies as objects that possess a certain degree of agency, of self-will, which can be used, activated, and perceived to the point of animistic animation. The unsentimental composition and almost meditative mood of Penney’s photos are unusual; the occasion doesn’t produce the kind of flag choreography one might expect. At the same time, the photographer could count on an inter-iconic reception; that is, he could count on the media to draw the connection to old pictures of flag use and other pictures coming out of Mali. Only two days before his picture of “liberated Timbuktu,” jubilant scenes had occurred when Malian and French troops entered the city. The population of Timbuktu was prepared, and waved the flags of France and Mali—many of which seemed as makeshift as the one in the boy’s hand.

The liberation of Timbuktu in northern Mali held particular symbolic weight. This was so not only because it meant capturing one of the recently established strongholds of the Islamist rebels and salvaging important cultural artifacts, like the city’s famous library and scripts. It was also because Timbuktu, as a legendary desert city, had great potential to produce an image that could remedy the memory of West Africa and France’s colonial history.18 The Malian and French flags, which marked the street scene on that day, articulated a multiplicity of feelings, ideological convictions, and media response patterns. Crucially, they also pointed to the absence of the banners introduced by the Islamist groups when their convoys arrived. In Timbuktu’s public sphere and in global media reports about the French intervention, the Islamist symbols (which are viewed by the international community as illegitimate, even illegal) were replaced by the color games of recognized nation-states.

The symbolic-goods industry responded quickly by dumping amalgamations of the two nations onto the Malian market. In Bamako, AFP correspondent Stéphane Jourdain photographed a sticker depicting François Hollande before a backdrop of Malian and French colors. The sticker was sold alongside images of Bugs Bunny and Malian soccer player Seydou Keita.19 French puppeteers on the television program Les guignols de l’info didn’t miss the opportunity to satirize the new color combinations. In an episode aired on January 28, 2013, they addressed the topic from a domestic angle.20 It starts with a scene resembling a primordial rite of military-colonial power and territorial assertion: the doll of a French soldier stands by a flagpole, next to an African straw hut. Then the Village People’s “In the Navy” starts playing and a rainbow flag is hoisted in place of the Tricolour. A voice-over announces that same-sex marriage has finally been accepted—indicating that the military, reputed bastion of homophobia, is losing all its inhibitions in the excitement over their success in Mali. The similarity between the rainbow flag and the PACE flag of the Italian peace movement (which became a global symbol in the course of worldwide demonstrations against the 2003 invasion of Iraq) adds some bite to Les guignols de l’info’s satirical declaration.

The Reluctant Flag

Of course, the situation in Mali and the images it has produced are anything but unambiguous. Although (or precisely because) the jubilation in the streets and squares of Bamako and Timbuktu was so effusive and apparently unambiguous, when François Hollande visited in early February 2013 in the manner of a military general, a growing chorus of critical voices emerged. These critics offered some context to the “Francophile fever” that seemed to have gripped the population of Mali, placing it in relation it to the country’s anticolonial struggles and the deep-seated rejection of the former colonial power.21 They also acknowledged that different generations in Mali had diverging opinions and feelings about France’s new triumphant presence and savior pose. Points of criticism included not only France’s tolerant attitude towards the Malian government, which had come to power through a military coup in 2012, but also that French and international media organizations were oversimplifying the situation in northern Mali: generalized references to terrorists and jihadis, for example, were thought to misrepresent the heterogeneous composition of the rebels.

On February 6, a few days after the intervention and Hollande’s visit, well-known Malian filmmaker and theorist Manthia Diawara published a long essay in which he not only analyzed the complex situation in Mali, but also offered ideas for a reorganization of the African state system—chiefly, a separation of nation and state. At the beginning of his text, which might be regarded as a kind of antinationalist manifesto, Diawara expresses his frustration with the way the Malians welcomed their supposed saviors. He uses the disparaging term “banner republic”—a play on “banana republic”:

I felt that the French intervention in Mali was a dose of realism that had to be taken with plenty of humiliation or shame. I thought my country was different from what I considered “Banner republics” (Républiques bannières), where the West must always help; countries that failed, where the people, seeing white soldiers arrive, rejoice like children at the sight of Santa. Seeing Malians dancing in the streets—as they had done at independence—to welcome the French army, was to me a still image [arrêt sur l’image], which on the one hand reminded me of our failed independence, our alleged national sovereignty, and on the other hand made me consider a full-blown return of French hegemony, like that of a father who doesn’t want to see his son grow up.22

Diawara sees this flag-waving as an interruption of the move toward emancipation, which started in the mid-twentieth century—the regression of a nation, be it one’s own or the one whose help one seems to require. The “banner republic” is a form of nationality for which the “banal nationalism” that social psychologist Michael Billig identified doesn’t suffice.23 In that situation, the waving of the flag is (or becomes) necessary to build emotional ties with the national project. Following Diawara’s lead, one could interpret Penney’s photograph of the flag-bearing child as an allegory for immaturity, for a lack of reflection about the double bias of nationalist and colonialist myths—the epitome of the “banner republic,” of its childlike affectedness in the smallest moment of gratitude, of its pride or haughty schadenfreude (regarding the misery in neighboring countries).

But Penney’s pictures are open to a wide variety of reactions and experiences, and not only in the trivial sense that everyone can see something different in them. In his presentation of the “false” French flag, which shows a subliminally reluctant, recalcitrant, undramatic flag-waving performance, the ritual of commitment to the nation seems to break down into its component parts, becoming thin and unstable. Rather than a submissive embrace, this seems to be a quietly eloquent refusal of the “banner republic.” The time of the Grande Nation and the time of the flag-waving boy are no longer synchronized, as they were in Barthes’s reading of the Paris Match cover photo. Rather, they are drifting apart, forming a heterochrony. The absence of any pathos or submission in the pose and gaze of the child reminds us that Michel Foucault considers colonies a part of the “counter-placements or abutment,” meaning the spatial order of heterotopia.24 In addition, one can sense the arbitrariness of the sign in light of its ostentatious materiality. The visual technology used—a digital SLR camera, by all appearances—articulates nuanced and brilliant colors through its high resolution and aperture, and primes the texture and surfaces of objects in extreme detail. The salesroom/stage is ironically reminiscent of a green screen. Next to the child, the flag, and the wooden block, we discover small and large canisters on the floor and wall, as well as a refrigerator. In this environment, the flag—which must have been sewn immediately prior, perhaps by the tailors in Bamako who in January 2013 started producing French flags on short notice, themselves becoming motifs for photojournalists25—is characterized by its individualizing materiality and its manual, preindustrial constructedness. This object, with its shining primary colors and crisp white, cannot (and should not) emancipate itself from its symbolic function. As a flag, it contributes a semiotic register to the picture; it “labels” the photo, decisively organizing its perception, interpretation, and use.

The other focal point, which, in tandem with the writing on the flag creates unpredictable connections and mixtures, is the face of the child. It lends Penney’s photo the signature of an affect-image, to the point where the presence of the flag has a mimetic quality and the face of the child has traces of the symbolic. In other words: any desired or expected message in the photo, any ideological appeal connected with the banner motif, becomes entangled in the dense assemblage of materiality and ambiguity. This “arrêt sur l’image,” to speak through Diawara, cannot be understood through vexillology (the study of flags and banners), political psychology, or semiotic analysis alone. Instead, a media studies problematization of the military and journalistic dispositifs offered in and through the photo should be carried out—as should a study of the photo as a volatile-erratic element in a socio-technological assemblage driven by reluctant political-affective energies. The floundering of sovereignty in the picture, which becomes emblematic of the complex relationship between subjectivity and sovereignty, opens up the pre- and trans-individual dimension of affect.

Starting from a critique of the concept of ideology and a theory of affect in capitalism—as advanced by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari and continued recently by Judith Butler, Brian Massumi, and Lauren Berlant—and then considering the child with the Tricolour, one can ask how “passionate or irrational attachments to normative authority and normative worlds” should be understood.26 Penney’s photo brings up such unconscious attachments or dependencies because it focuses on the attachment of a child, who is dependent per se—particularly on his parents—and who is subject to household and societal norms, and who experiences this subjection as passion (love, etc.). For Lauren Berlant, children (partly because of their fundamental dependence) feel a “cruel optimism” in which each imposition and adjustment by the authorities is understood as a contribution to a better life: “Children organize their optimism for living through attachments they never consented to making … they make do with what’s around that might respond adequately to their needs.”27

The child in Penney’s picture picks up the Tricolour because that is what’s around. Perhaps he sees it as a sign of hope for change and improvement. Or maybe he sees it as a sign of authority that, however temporary, supplements or replaces the existing authorities. This allows spectators to reflect on the relationships between childhood and nation, between dependence and sovereignty, between perceived norms and normative feelings. Furthermore, viewers’ own individual and trans-individual attachments to the nation—the French one in this case—and the neoimperial regime in which the nation-state is integrated are worth reconsidering. 28

From the point of view of an extended political affect theory, the “flag” (as a concrete material thing and as an abstract symbol) is only interesting in its relationality, as a thing among things, an actant among actants—only interesting when it is experienced as part of an event, as an element of affective encounters or a socio-technological fabric, which is materially and virtually changed in and through these frames. Why not transform the sub-academic subject of vexillology by developing an anti-essential definition of “flag,” placing it beyond the reach of ideology-critical reflexes, so as to make a differentiated consideration of the pragmatism and performativity of flags possible? In the course of such a reflection, it becomes important to consider the flag’s presence in heterotopic and heterological image spaces, in terms of its expressiveness and political instrumentality, its affirmative and subversive nature, its banality as well as its great potential for scandal and excitement. All legitimate critiques of the spasms of the “République bannière” considered, the analysis of the flag-wavers in Mali may help make sense of the role flags play in a post-normative, deregulated world order, and thus contribute to the economy of affects in our prolonged state of emergency. In short: they are phantasmic crutches.

Named after a breed of small cats native to Africa.

For a helpful overview of the situation in Mali at the time of the intervention, see Stephen Smith, “In Search of Monsters: On the French Intervention in Mali,” London Review of Books, February 7, 2013.

See Forum pour un Autre Mali (FORAM), “Mali: Chronique d’une recolonisation programmée,” April 6, 2013, Afrik.com →; John Ahni Schertow, “No to the Recolonization of Mali,” Intercontinental Cry Magazine, March 4, 2013 →; Alexander Mezyaev, “Military Intervention in Mali: Special Operation to Recolonize Africa,” Global Research, January 14, 2013 →; “France and the Recolonisation of Mali,” Revolutionary Communist Group—Fight Racism! Fight Imperialism! no. 231 (Feb.–March 2013) →.

Joe Penney, “Mali’s War: Far From Over,” Photographer’s Blog, Reuters, March 22, 2013

John Berger and Jean Mohr, Another Way of Telling (New York: Vintage, 1982), 83.

Roland Barthes, Mythologies, trans. Jonathan Cape (New York: Hill and Wang, 1972), 260.

Ibid., 260.

Ibid., 261.

Barthes didn’t pay attention to these details, which are available on the cover and inside the issue of Paris Match. Several gaps and blind spots in his analysis have been pointed out over the last few years. Nicholas Mirzoeff, for example, noted that the Paris Match cover had an eerie resonance with a practice of the anticolonial FLN in Algeria: the FLN photographed captured sub-Saharan soldiers—recruited by the French to implement colonial oppression—after their execution, doing precisely the same flag salute (See Mirzoeff, The Right to Look: A Counterhistory of Visuality (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011), 244.) Canadian artist Vincent Meessen tried to locate Diouf Birane, the adolescent on the Paris Match cover, for his video project Vita Nova(2009). He discovered that Birane had died in Senegal in 1980. But in the course of his research in Ouagadougou, he happened upon one of Birane’s comrades, who also attended the 1955 event and was also depicted in the famous issue of Paris Match. He also discovered something that was missing from Barthes’s biography and accounts of his anticolonial engagements: one of Barthes’s grandfathers, Gustave Binger, had been a high-ranking French colonial officer in West Africa in the second half of the nineteenth century. (See T. J. Demos, Return to the Postcolony: Specters of Colonialism in Contemporary Art (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2013).)

In the past few years, young migrant activists have brought the Vichy poster back from the archives, reappropriating and defacing it to recode the national project and promote a tolerant, anti-Islamophobic, and antiracist society. (See PIR, “Rebeus, Renois, tous solidaires… Et vous?,” Les Indigènes de la République no. 8 (November 2010) → and “Mois du graphisme à Echirolles,” Le Blog de guy, December 20, 2012 →.) This reference to the Tricolour and its critical rededication is problematic in itself. The national symbols, particularly the republican connotations of the Tricolour, merit a discussion of their own today—even if they have received one before. In 1968, for example, the French Left vehemently discussed these questions. (See Le Rouge, the short ciné-tract that painter Gérard Fromanger produced in 1968 with Jean-Luc Godard, which shows the color red pouring over the white and blue parts of the Tricolour →. The repression of colonial history has recently lead to a widespread academic and pop cultural discourse in France. The highly successful feature film Indigènes by Rachid Bouchareb, for example, which thematized the forgotten and ignored role of North and West African soldiers in France’s World War II efforts, incited a firestorm of discussion. Revisionist histories of French colonialism emphasize the significance of the flag in this context. Pascal Blanchard and Sandrine Lemaire’s Culture impériale, 1931–1961 (2011), for example, focuses on another of the Vichy government’s propaganda images featuring the Tricolour; incidentally, they also show a film poster for Indigènes intended for the international market, which concentrates the film’s plot into a blue-white-red fog (even here, the motif of the Tricolour is used for atmosphere’s sake.

It is worth noting that Rouch’s 1955 Les maitres fous, which documents (and stages) the dances and rituals of the Hauka religion in British-colonized Niger, shows a Hauka flag parade, which is of great structural importance to the film. This parade, in turn, references a British flag ritual called “Trooping the Colour”; see Erhard Schüttpelz, Die Moderne im Spiegel des Primitiven: Weltliteratur und Ethnologie (1870–1960) (Munich: Fink, 2005).

Émile Durkheim, Die elementaren Formen des religiösen Lebens (1912), trans. Ludwig Schmidts, (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1981).

Carolyn Marvin and David Ingle, Blood Sacrifice and the Nation: Totem Rituals and the American Flag (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999).

See Urte Evert and Daniel Hohrath, “Die Zeichen der Krieger und der Nation: Fahnen und Flaggen,” Farben der Geschichte. Fahnen und Flaggen, ed. Daniel Horath in cooperation with Urte Evert and Steffi Bahro, commissioned by Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin 2007, 17. In the mid-nineteenth century, abolitionist preacher Henry Ward Beecher said: “A thoughtful mind, when it sees a Nation’s flag, sees not the flag only, but the Nation itself; and whatever may be its symbols, its insignia, he reads chiefly in the flag the Government, the principles, the truths, the history which belongs to the Nation that sets it forth.”

Durkheim, Die elementaren Formen des religiösen Leben, 326.

The motif is also of interest to ambitious photographers like Seth Butler; see Tattered: Investigation of an American Icon, 2010 →.

Robert Davoine, Tombouctou. Fascination et malédiction d’une ville mythique (Paris: Harmattan), 2003.

Stephane Jourdane, “Sticker à l’effigie de François Hollande, le 21 mars 2013 au marché Dabanani de Bamako,” DirectMatin.fr, March 22, 2013 →.

“La France hisse le drapeau au mali—Les guignols de l’info du 29/01/13.”

For a further explanation of some of the positions around “Francophile Fever.”

Manthia Diawara, “Ce qui serait arrivé si la France n’était pas intervenue au Mali,” Slate Afrique, February 6, 2013 →.

Michael Billig, Laughter and Ridicule: Toward a Social Critique of Humor (London: Sage, 2005).

Michel Foucault, “Von anderen Räumen,” Dits et Ecrits. Schriften, vol. 4 (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 2001), 931–942.

See the picture a Reuters photographer took on January 24, 2013 of tailor Abdoulay Cissuma sewing a flag in Bamako’s central market →.

Lauren Berlant, Cruel Optimism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011), 183.

Ibid., 296.

In connection with a politics of affects, new sociopsychological and neurological studies on the effect of seeing a flag should be undertaken. Their empirical results may offer revelations about the transformation of political space in a pre- and post-discursive affect-public. See Ran R. Hassin, Melissa J. Ferguson, Daniella Shidlovski, Tamar Gross, “Subliminal Exposure to National Flags Affects Political Thought and Behavior,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol.104, no.50 (December 11, 2007): 19757-19761; Laura Cram et al., Strathclyde University “Mood of the Nation Quiz — A Survey with a Twist,” 2012 → and Guido Michels, “Neuronen für Deutschland. In Berlin vermessen Forscher die Bundesbürger bei der Produktion des Nationalgefühls,” Der Spiegel, June 25, 2012.

Category

Translated by Leon Dische Becker. This article originally appeared (in a slightly different German version) in Heterotopien. Perspektiven der intermedialen Ästhetik, ed. Nadja Elia-Borer et al. (Bielefeld: Transcript, 2013).