In 2005 the Sfeir-Semler Gallery opened in Beirut, in an industrial quarter called Karantina.

Some of you already know that Karantina was the site of a brutal massacre of civilians in 1976. I am not going to talk about this here.

The Sfeir-Semler Gallery opened on the fourth floor of a large former warehouse. It is an 800-square-meter space, with clean four-meter-high, sixty-centimeter-thick white walls, smooth concrete floors, and diffuse northern lighting all around. It is the white cube of white cubes. We have never had a space this beautiful in Beirut. Some of us have been waiting for a space like this for forty years.

The name of the person who opened the gallery is Andrée Sfeir. Andrée also owns a gallery in Hamburg that I work with. And when she opened the new space in Beirut, Andrée began asking me about the possibility of exhibiting my project called The Atlas Group (1989–2004) in the Beirut gallery.

I should say that The Atlas Group (1989–2004) is a project I worked on for fifteen years. It is a project about the wars in Lebanon, but it is also a project I have never shown in Lebanon. For some reason, I could never do it. I always feared that something would happen to the works. It’s not that I thought it would be censored or anything like that. I just felt that the works would somehow be affected, though I could not say exactly how.

In 2005 I refused Andrée’s persistent offers to show this work in Beirut. And I tried to explain my feelings to her, without much success.

In 2006 she asked me again. I refused again.

In 2007 she asked me again. I refused again.

In 2008 she asked me again. But this time, I agreed. I don’t know why. I just agreed to do it.

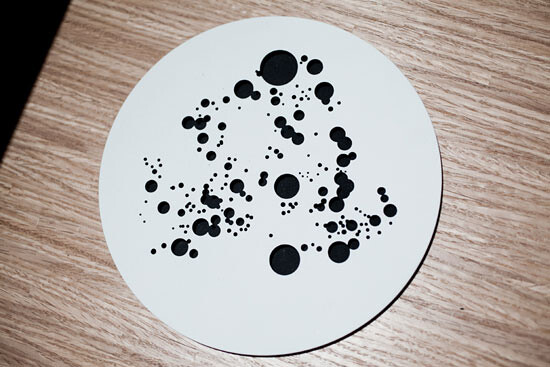

I proceeded to print and frame my photographs, to produce the sculptures and videos, to design the exhibition space, to print all the wall texts. And I sent these to the gallery in Beirut.

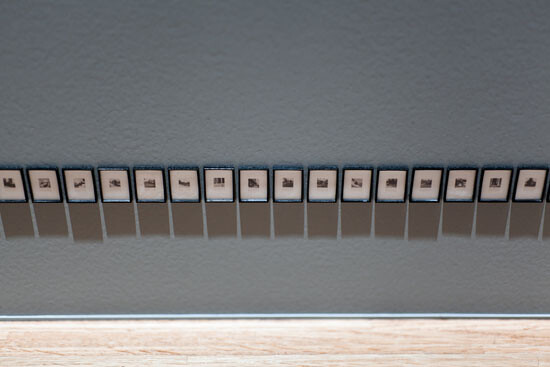

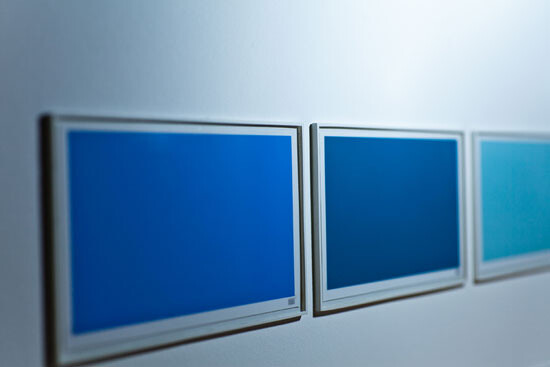

Three weeks later I went to the gallery to see my mounted display, and this is what I confronted. I found myself facing the reduction in scale of every single one of my artworks to 1/100th of their original size. Each and every artwork I had done now appeared to me as a miniature object.

At first, and given my psychological history, I thought my mind was playing tricks on me. I was convinced that I was in the midst of a psychotic episode.

So I called Hassan. Hassan is an installer in the gallery. I asked him to stand with me in front of this “situation” and to describe to me what he saw.

Hassan arrived, and immediately he began to marvel at the detail of the small-scale reproductions, which proved to me that the works also appeared to Hassan at 1/100th of their original size. But I also know from my own reading in psychology that, in the history of psychiatry, no two people have ever experienced the exact same psychotic episode at the same time. And I doubted that this situation was a historical exception. I then became convinced that I was not in fact in the midst of a psychotic episode but that my assistant, my framer, and my printer were behind all of this. I became convinced that, without telling me, they had decided to make everything small. They produced all my works at 1/100th of their size as some kind of practical joke. Or better yet, as some kind of gift, because they know how fond I am of all things miniaturized.

A couple of hours later, when my assistant, my framer, and my printer arrived, they were all struck by the technical aspects of the miniaturization. They assured me that they had nothing to do with this. In fact, they felt that the joke was on them. They also felt betrayed by the fact that I went behind their backs and chose to work with another team on this piece, as if they were not up to the technical challenge. One of them even said to me spitefully: your works look better small anyhow, when one cannot see them well.

Hearing this, I immediately realized that I had no other choice. I was forced to face the fact that, in 2008, in Beirut, all my artworks shrank.

So I decided that I needed to build a new white cube better suited to the new dimensions of my works. And that is exactly what I did.

All photos by Jakob Polacsek

Dedicated to Carlos Chahine and Markus Reymann