I have to thank Rijin Sahakian for a reasonable rebuttal to the first half of my essay. It is certainly unreasonable for me as someone who resides in the United States to gloss over the violence and destruction of the Iraq War. It was not my intention to say that the efforts of COIN were in fact effective in actually “protecting the population,” but instead to point out a methodology of social relationships that worked in tandem with violence. I have no desire to be a provocateur in regards to the horrible atrocities of Iraq or El Salvador, for that matter. I admit my essay could have made this point much more transparent. That said, I hope the readers find the move toward social relationships across a range of political aspirations instructive. As Brian Kuan Wood said to me, “What is worse? Killing people or making friends and then killing them?”

—Nato Thompson

Continued from “The Insurgents, Part I: Community-Based Practice as Military Methodology”

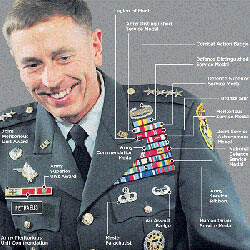

The lessons that General David Petraeus deployed in Mosul came out of a combination of research and first-hand experience. Although the Iraq War was his first time in combat, he had traveled to El Salvador in 1985 with General Jack Galvin to see up close what a counterinsurgency campaign looked like. The US under Carter and Reagan was determined to stop the spread of left-wing governments worldwide, fearing Cuban and Soviet interference in both El Salvador and Nicaragua. In El Salvador, they sent in military “trainers” (they balked at the term “advisors” due to its association with the Vietnam War) and weapons (nearly $5 billion in aid, total) to support the right-wing government that was decimating the revolutionary movement of the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN). The US trainers facilitated a conflict that came to be regarded universally as a human rights nightmare. One million people were displaced and, according to the United Nations, seventy-five thousand people were killed in a nation of roughly 5.5 million. The lessons of counterinsurgency that Petraeus witnessed in El Salvador, with its back-end reliance on personal violence such as torture, certainly foretold an experience in Iraq. In State Department circles, however, the conflict in El Salvador was viewed as somewhat of a success since the FMLN didn’t come to power.

The US generals and advisors behind the counterinsurgency (or “COIN” in military speak) in El Salvador had to engage in perverse double-speak, since the right-wing government they were supporting not only lacked legitimacy in the eyes of the people of the country, but also in the eyes of the US military. According to Fred Kaplan, Brigadier General Fred Woerner, who headed up the military strategy team in El Salvador, “drafted a National Campaign Plan that addressed what he called ‘the root causes’ of the insurgency. It laid out a program of rural land reform, urban jobs, humanitarian assistance, and basic services for a wider segment of the population.”1 Ironically, these were precisely the kind of policies the rebels were fighting for.

The language surrounding the means of winning the revolution by General Woerner sounds eerily like the FMLN’s intended ends. As a 1991 RAND paper aptly summarized,

In El Salvador, as in Vietnam, our help has been welcome but our advice spurned, and for very good reason. That advice—to reform radically—threatens to alter fundamentally the position and prerogatives of those in power. The United States, with its “revolutionary” means of combatting insurgency, is threatening the very things its ally is fighting to defend. Those reforms that we have deemed absolutely essential—respect for human rights, a judicial system that applies to all members of Salvadoran society, radical land redistribution—are measures no government in El Salvador has been able to achieve because they require fundamental changes in the country’s authoritarian culture, economic structure and political practices.2

In January 2007, Petraeus replaced General George Casey as commanding general in Iraq. During his confirmation hearings, Petraeus articulated his idea for “the surge,” which he saw as his opportunity to put into practice everything he had laid out in the Counterinsurgency Field Manual 3-24.3 The US military would firm up the new Iraqi government, provide safety for its citizens, separate the extremists from the moderates, and bolster local police forces. He also brought in several advisors who had long supported the growth of COIN thinking within the US military, including an Australian lieutenant colonel named David Kilcullen. Kilcullen had written a widely circulated document titled “Twenty-Eight Articles,” which condensed the lessons of counterinsurgency into a how-to guide for soldiers. Petraeus asked Kilcullen to again write up a simple list explaining COIN strategy to soldiers involved in the surge. According to Fred Kaplan,

[Kilcullen] listed ten things they needed to do, chief among them: “Secure the people where they sleep” (because securing them only in the daytime will make them more vulnerable to revenge by insurgents at night). Another point: “Get out and walk.” Armored vehicles were necessary to get from one place to another, but once you’re there, mingle among the people; the vehicles offer self-protection but “at the cost of a great deal of effectiveness”; patrolling by foot is the only way to build trust, and building trust is essential to gathering reliable intelligence.4

A militarized campaign of “getting to know people” was under way. The surge didn’t produce immediate results, and over the first few months, casualties among US soldier actually spiked (due in large part to their greater presence on the ground). But after the first half of 2007, civilian and troop casualties declined dramatically. Progress, from the US perspective, was finally occurring in an embattled landscape. Admittedly, the term “progress” is cynical from the start. The US effort in Iraq has left over 115,072 civilians dead, according to the Iraqi Body Count project.5

With the perceived success in Iraq, Petraeus emerged as a miracle worker. In the eyes of administration officials, he had taken an impossible situation and somehow turned it around. On April 23, 2008, President Bush nominated Petraeus to run US Central Command (USCENTCOM), located in Tampa Bay, Florida. Then, two years later, on June 23, 2010, President Obama nominated Petraeus to replace General Stanley McChrystal as the head of the International Security Assistance Force in Afghanistan—the thinking being that if COIN could work in Iraq, maybe it could work in Afghanistan as well. Petraeus’s kinder, gentler form of warfare also seemed to fit perfectly with the public image of President Obama, who had run his campaign in large part on the American public’s frustrations with the bellicose blundering of George W. Bush.

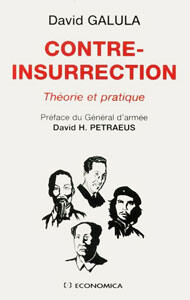

When it came to COIN, the most important influence on the thinking of David Petraeus was a French military strategist named David Galula, who many regard as the historic expert on counterinsurgency. His 1964 book Counterinsurgency Warfare: Theory and Practice lived in relative obscurity until the US military rediscovered COIN in the early 2000s. Galula lived one of those peculiar lives marked by consistently being in the center of historic events. A French citizen born in Tunisia in 1919 and raised in Casablanca, he graduated from the prestigious Saint Cyr military academy in 1939. In 1941, he was expelled from the officer corps under the Vichy governments ban on Jews. He relocated to North Africa. There he joined the French Resistance during World War II, and then rejoined the French military. In 1945, he was deployed to China, where he witnessed first hand the Communist revolution headed by Mao Tse-tung, who was battling the Koumintang nationalists. Galula wound up being captured and held for a week. It was in captivity that he began to notice that Mao was fighting a very different kind of war. As Adam Curtis writes,

Put simply—there was no conventional army any longer, the new army were the millions of people the insurgents moved among. And there were no conventional victories any longer, victory instead was inside the heads of the millions of individuals that the insurgents lived among. If they could persuade the people to believe in their cause and to help them—then the conventional forces would always be surrounded—and would be defeated no matter how many traditional battles they won.6

In 1956, Galula volunteered to fight in the Algerian War. He wanted to test out a series of ideas he had been formulating on counterinsurgency. He deployed them in a mountain village, where he hoped to talk the revolutionaries into changing their minds:

In March 1957, I was well in control of the entire population. The census was completed and kept up to date, my soldiers knew every individual in their townships, and my rules concerning movements and visits were obeyed with very few violations. My authority was unchallenged. Any suggestion I made was promptly taken as an order and executed. Boys and girls regularly went to school, moving without protection in spite of the threats and terrorist actions against Moslem children going to French schools. Every field was cultivated. As they recognized the difference between their prospering environment and those surrounding areas still in the grip of hostilities, villagers were easily convinced of the need to preserve their peace by helping to prevent rebel infiltration.7

Counterinsurgency is a method—a method of talking and coercing people. If you take away the use of violence (which is like taking the flour out of a cake), COIN bears a remarkable similarity to that left-wing, walking-the-beat technique known as grassroots organizing. In the current landscape of everyday life—whether in Baghdad or in Oakland—culture, the built environment, politics, and media are all inextricably intertwined. In this situation, the methods of counterinsurgency have civic overtones.

The strategy of getting to know people is employed by all kinds of activist groups, from grassroots organizations, to church organizations (the Mormons and Jehovah’s Witnesses know a thing or two about going door to door), to community-based artists, NGOs, and civic organizations. While it’s unlikely that very many of these do-gooder groups have studied the writings of David Galula, they have probably been influenced by the writings of Saul Alinsky.

Born in 1909 to Russian Jewish immigrants in Chicago, Alinsky, like so many others, became radicalized during the lean years of the Great Depression. He organized in the predominantly Slavic neighborhood known as Back of the Yards, made famous by Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle. A dirty mess of meat packing plants, the working conditions there were the kind of grave injustice that fueled Alinsky’s visionary pragmatism. He was a realist and refused allegiance to any ideology. His efforts became the foundation for what has become contemporary community organizing.

Not at all unlike the community-building strategies described in the Counterinsurgency Field Manual 3-24 or in the writings of David Galula, Alinsky’s community organizing methodology relied heavily on the creation of a network of councils whose combined interests resulted in real political power. The politics and tactics of the movement were often crafted in face-to-face meetings among community members. Alinsky’s community organizing had the feel of a mobilized network of focus groups. His style was combative and nonviolent, and he regarded the battle for public opinion as fundamental to successful community organizing. Here are his thirteen principles of community organizing, from his seminal book Rules for Radicals:

1. Power is not only what you have but what the enemy thinks you have.

2. Never go outside the experience of your people.

3. Whenever possible, go outside the experience of the enemy.

4. Make the enemy live up to their own book of rules.

5. Ridicule is man’s most potent weapon.

6. A good tactic is one that your people enjoy.

7. A tactic that drags on too long becomes a drag.

8. Keep the pressure on.

9. The threat is usually more terrifying than the thing itself.

10. The major premise for tactics is the development of operations that will maintain a constant pressure upon the opposition.

11. If you push a negative hard and deep enough it will break through into its counterside.

12. The price of a successful attack is a constructive alternative.

13. Pick the target, freeze it, personalize it, and polarize it.8

Similar to Mao Tse-tung’s dictum that people are the sea that revolution swims in, Alinsky’s rules for radicals come out of a deep understanding of how to manipulate public perception in an uneven playing field. In essence, Alinsky’s rules describe how to organize a nonviolent insurgency, which is one way to characterize community organizing and socially engaged art. Perhaps it is no wonder then that the current organizing methods of the Tea Party have been said to follow Alinsky’s sage examples.

While Petraeus didn’t exactly organize community meetings to improve labor standards, as he took over the war in Afghanistan he was primed to organize meetings with tribal leaders. His credibility after Iraq was at an all-time high, and the Obama Administration was eager to claim victory in the country where the Soviet Union famously failed. With support increasing in the White House for Petraeus’s hearts-and-minds strategy, so too did the budget for more advisors, translators, social programs, and payoffs. One of the most talked-about and controversial of these programs was called the “Human Terrain System.”

Human Terrain

The Human Terrain System (HTS) was launched in February 2007 by the US Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC). Its name reveals plenty about its aspirations. Just as the military needs to understand the landscape of the countries it invades, so too does it need to understand the complexity of the people that live there.

According to its website, “The Human Terrain System develops, trains, and integrates a social science based research and analysis capability to support operationally relevant decision-making, to develop a knowledge base, and to enable sociocultural understanding across the operational environment.”9 The program had an initial budget of $20 million, which funded five teams in Iraq and Afghanistan. These “Human Terrain Teams,” which included translators and anthropologists, were supposed to gather intelligence by meeting face to face with community leaders and latching onto military operations.

HTS met with almost immediately controversy, especially in the halls of academe. The militarization of anthropology and anthropologists went over like a lead balloon. In November 2007, the Executive Board of the American Anthropological Association issued a formal rebuke of the HTS program:

In the context of a war that is widely recognized as a denial of human rights and based on faulty intelligence and undemocratic principles, the Executive Board sees the HTS project as a problematic application of anthropological expertise, most specifically on ethical grounds. We have grave concerns about the involvement of anthropological knowledge and skill in the HTS project. The Executive Board views the HTS project as an unacceptable application of anthropological expertise.10

However, this strong condemnation from one of anthropology’s most distinguished bodies didn’t stop some anthropologists from participating in HTS. Certain academics who normally would never find themselves at the center of military culture were suddenly thrust into the limelight, as the desperation for new solutions on the part of the US military forced atypical cross-disciplinary relationships to emerge. Such was the fate of the enigmatic figure Montgomery McFate.

In 2005, Montgomery “Mitzy” McFate co-wrote, with Andrea Jackson, a short piece titled “An Organizational Solution to DOD’s Cultural Knowledge Needs.” It argued for the creation of a new department to consolidate cultural information during a war effort. “Establishing an office for operational cultural knowledge would solve many of the problems surrounding the effective, expedient use of adversary cultural knowledge.”11 The timing was perfect, as interest in COIN was growing among the military brass. McFate, perhaps knowingly, was clearing a path for a future department in which she would play an important role.

Holding a PhD in anthropology from Yale and a law degree from Harvard, Montgomery McFate took a circuitous route to the inner sanctum of the Department of Defense. In the same year that she published the article on the DOD, she also published an odd article titled “Anthropology and Counterinsurgency: The Strange Story of their Curious Relationship.” Here McFate made a series of zigzagging rhetorical maneuvers to demonstrate that anthropology’s fear of replicating colonialism had led the discipline down a path of self-flagellating irrelevance. McFate argued that fear of complicity had forced anthropology to run from any kind of political relevance—such as cooperation with the US military:

The retreat to the Ivory Tower is also a product of the deep isolationist tendencies within the discipline. Following the Vietnam War, it was fashionable among anthropologists to reject the discipline’s historic ties to colonialism … Rejecting anthropology’s status as the handmaiden of colonialism, anthropologists refused to “collaborate” with the powerful, instead vying to represent the interests of indigenous peoples engaged in neocolonial struggles.12

Most of the academic community and many in the broader media saw McFate’s arguments as a rationalization of a position of power, but McFate, who wasn’t afraid to challenge the hermetic nature of academia, argued that in fact helping the military could lead to saving lives. “If you understand how to frustrate or satisfy the population’s interests to get them to support your side in a counterinsurgency, you don’t need to kill as many of them. And you certainly will create fewer enemies.”13

To digress briefly, because biography has a way of exhibiting its own cultural turns: McFate’s story is demonstrative of an evolution in the uses of culture. Montgomery McFate was first Montgomery Carlough, born in 1966 to bohemian parents living on a houseboat in Sausalito, California, just north of San Francisco. Her parents were acquaintances of Bay Area counterculture icons such as Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Jack Kerouac. It is not surprising, then, that McFate took her own counterculture journey through the 1980s Bay Area punk scene. According to her childhood friend and now accomplished author Cintra Wilson, “She walked in the door one time and it was all black jeans, black combat boots, tight black sweater and this big black hat with a big black veil. It was this great look … we called her ‘Satan’s beekeeper’ … She was goth before anybody was goth.”14 Like many a young Bay Area punk, Carlough/McFate found her way to UC Berkeley in 1985 and took up the study of anthropology.

McFate went on to use her rhetorical skills to point out the disastrous inefficacy of both academia and the military. Surprisingly, it was the military that was more amenable to listening. They made a department for her—the Human Terrain System.

Life: An Extended Performance

What COIN projects like the Human Terrain System attempt to accomplish is something that myriad fields are trying to achieve: shaping the opinions and actions of a group of people, the premise being that social relationships have a medium and can be shaped toward a form. The cultural turn in the military over the last thirty years has coincided with a cultural turn in a variety of other fields, from anthropology to marketing to socially engaged art to policing and community organizing.

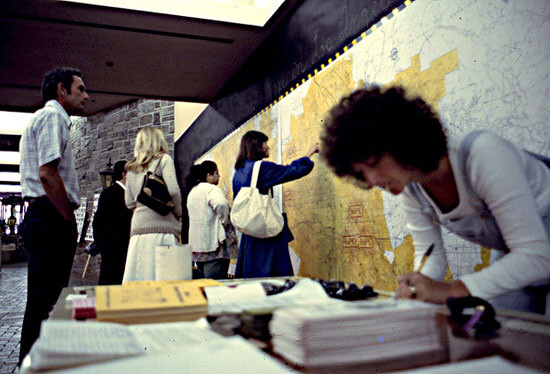

It is 1993. Black youth in Oakland have a public image problem. The war on drugs is in full effect and the mainstream media’s portrayal of black youth relentlessly presents a class of people as pathologically violent. Enter the artist Suzanne Lacy, who has been volunteering in Oakland public high schools teaching classes on media literacy. She organizes a series of conversations with teachers and students—not unlike something Alinsky would organize. Some of the students are interested in having their voices heard in the media sphere, a realm from which they are usually locked out. Working with Lacy, they produce an event they hope will allow them back in. The performance, titled The Roof is on Fire, features 220 high school students sitting in parked cars on a roof talking about their lives. It is an odd encounter, but the audience and news crews in attendance hear the concerns of these kids first hand. The performance is part media stunt, part community organizing effort, part art project.

Suzanne Lacy studied under artist Allen Kaprow at the University of California at San Diego. Kaprow was renowned for his Happenings, a hybrid form of participatory performance. He was a major proponent of turning art into life: “The line between the Happening and daily life should be kept as fluid, and perhaps indistinct, as possible.” But turning art into life is not such an easy task when the political realities of daily life often diminish the public sense of what constitutes art. When Lacey was studying under Kaprow in the mid-’70s, second-wave feminism was taking hold in the arts, especially on the West Coast.

In 1977, Lacy created the project Three Weeks in May, which focused on violence against women. She described it as an “extended performance” occurring over three weeks. The project unfolded in a series of life-like activities that mimicked the techniques of a community organizing campaign. Speeches by politicians, press events, radio interviews, art performances, and self-defense workshops were all choreographed movements in this theater of political life.

Lacey built upon the work of Kaprow by attempting to tackle political issues—by bringing art not only into daily life, but also into political and social life. She tried to address the contextual realities of power. This places her work in conversation with other discourses that have attempted to shape everyday life—that regard people as the center of gravity. Lacey and the likes of David Galula, Saul Alinsky, and David Petraeus employ community organizing techniques to mold the “human terrain.”

It Isn’t Easy

Easier said than done. Changing public attitudes is no mean feat, particularly when you are an invading, colonizing force. With the perceived success of the surge in Iraq, the US refocused on Afghanistan, with an even larger emphasis on the role of Human Terrain Teams (HTTs). The fit was less than ideal. Poorly trained anthropologists trying to blend in with and give advice to highly trained soldiers came with its own culture clash. According to retired colonel Steve Fondacaro, who headed up the Human Terrain System program, “We’re like a germ in the body of [the Army] … All of their systems are sending white blood cells to puke me up.”15

The US is not a monolithic machine. It is a cumbersome infrastructure with competing if not outright conflicting interests. As much as the stated desire to protect and study the population was part of the mandate of the HTTs and the overarching COIN operations in general, these operations often found themselves working alongside the vast brutality that is the legacy of US military conquest.

Recruiting for the HTTs wasn’t easy, even with the fairly large paycheck that was offered. Initially, the ideal candidate spoke Arabic and had a PhD in anthropology with a focus on the Middle East. But the qualifications were quickly relaxed to include anyone with a graduate degree in anthropology, and soon enough, anyone with a graduate degree in almost any related field. As one might imagine, having a graduate degree in sociology doesn’t exactly prepare one for learning about the intricacies of Pashtun tribal culture in the midst of a war. Journalist Robert Young Pelton followed an HTT around Afghanistan and learned just how odd the fit was:

HTTs are supposed to bring down the cultural barrier between the military and the locals, but the biggest enemy is the natural inclination of troops to be troops, not social workers. Strangely enough, the Taliban is far more expert at meeting the basic needs of Afghans: namely, by fighting the corrupt central government and providing justice and security. Until that changes, the Afghans will be more inclined to identify with the “enemy” than the well-intentioned guests.16

A bad fit in a war zone doesn’t just lead to bad information, but also to the loss of life. On November 4, 2008, thirty-six-year-old HTT member Paula Loyd was conducting routine surveys in a village in Kandahar Province. She had graduated from Wellesley with a degree in anthropology and had spent years as a development worker in the region. But all her training did not prepare her for the man she was interviewing to suddenly douse her in gasoline and set her on fire. She died from her burns a few months later. Her attacker, Abdul Salam, was shot while in custody by Loyd’s HTT colleague and hired mercenary Don Ayala. Ayala was put on trial and found innocent.

The story is gruesome and bewildering. Of course war is violent and the death of one HTT member isn’t exactly a condemnation of the program. But just such a narrative took hold in the media. There was something about a blonde-haired do-gooder being set on fire that didn’t sit well with the news-watching public. It produced a backlash of skepticism regarding the effectiveness of the Human Terrain System program.

On May 2, 2011, at 11:35 p.m., President Obama announced that US troops had raided a compound in Pakistan and killed Osama Bin Laden. It was perhaps the first time a US President could claim an unqualified victory in 9/11-related military expedition. It was enough to put the brakes on COIN operations in Afghanistan. On June 22, 2011, President Obama announced that by the end of the year, ten thousand troops would be withdrawn from Afghanistan. By the end of 2012, thirty-five thousand more would be withdrawn. Then on June 30, 2011, David Petraeus was confirmed as the director of the Central Intelligence Agency. He left his post in Afghanistan. The priorities of the US military had radically shifted.

From here the story gets fairly tabloid-esque. Steve Fondacaro had already been let go in June 2010. Then it was discovered that Montgomery McFate, writing under the pseudonym “Pentagon Diva,” was the person behind the entertainingly titled blog I luv a man in Uniform. The blog gushed over the hotness of the commanders of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. The last post, written on June 15, 2008 reads, “Why is Dave Kilcullen so totally, spankingly HOT? Is it because he’s an Australian Army officer with a PhD in anthropology and operational experience in multiple theaters? Is it because he gives full body contact hugs? Is it because he was instrumental in Petraeus’ surge strategy in Iraq?” Needless to say, this discovery might have been a contributing factor in McFate’s dismissal from the Human Terrain System program in August of 2010.

The tabloid story doesn’t end there. Famously, Petraeus was outed as having an extra-marital affair with his biographer, Paula Broadwell. This happened after Tampa Bay socialite Jill Kelley, a friend of Petraeus, received threatening emails regarding her friendship with the general. She turned the emails over to the FBI. The internet trail eventually led back to Paula Broadwell. The scandal culminated in the resignation of Petraeus. It also took down General Paul Allen, who had taken over Petraeus’s position in Afghanistan. Emails between himself and Jill Kelley came to light, and although Allen was cleared of any wrongdoing, he stepped down a few months later.

Means and the End

It might seem counterintuitive to compare the arts and the military. Apples and oranges for sure. But while the ends pursued by these two spheres are radically different, aspects of their means are startlingly similar. Comparing examples according to means and not ends offers a new method for understanding formal approaches to the construction of a public. As the manipulation of culture becomes a major priority across a range of disciplines, it might prove instructive to overlook disciplinary boundaries and simply compare methodologies.

The cultural turn in the military was no small initiative. It reshaped the war in Iraq and put thousands of troops on the ground in Afghanistan. While its urgency has waned for the moment, the interest in military force operating on the level of culture will only grow as wars increasingly take place in urban environments characterized by mediated cultural relations. This is the territory of all cultural actors, be they artists, police officers, marketers, or pedagogues. The different ends may or may not justify the means, but the means themselves bear a remarkable resemblance.

This comparison comes out of a sense of urgency. The militarization of social relationships and its concomitant violence would not be happening if they were not in some way effective. That is to say, the tools of counterinsurgency are not going away. They are powerful instruments for all sides. It might seem inappropriate to learn from the forces of power that use them, but hopefully, in seeing the cultural turn in the military as a descendent of the techniques of colonialism, one can begin to place methods of resistance in a new methodological light.

Fred Kaplan, The Insurgents: David Petraeus and the Plot to Change the American Way of War (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2013), 28.

Benjamin C. Schwarz, American Counterinsurgency Doctrine and El Salvador: The Frustrations of Reform and the Illusions of Nation Building (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 1991). See →.

See →.

Kaplan, The Insurgents, 266.

See →.

Adam Curtis, “How to Kill a Rational Peasant,” The Medium and the Message (blog), BBC.co.uk, June 16, 2012. See →.

David Galula, “From Algeria to Iraq: All But Forgotten Lessons from Nearly 50 Years Ago,” RAND Review Vol. 30, No. 2 (Summer 2006). See →.

Saul Alinsky, Rules for Radicals: A Pragmatic Primer for Realistic Radicals (New York: Random House, 2010 (1971)), 127–30.

See →.

“American Anthropological Association’s Executive Board Statement on the Human Terrain System Project,” American Anthropological Association, Nov. 6, 2007. See →.

McFate and Jackson, “An Organizational Solution to DOD’s Cultural Knowledge Needs,” Military Review (July–August 2005), 18–21. See →.

McFate, “Anthropology and Counterinsurgency: The Strange Story of Their Curious Relationship,” Military Review (March–April 2005): 24–38. See →.

Matthew B. Stannard, “Montgomery McFate’s Mission: Can One Anthropologist Possibly Steer the Course in Iraq?” April 29, 2007, sfgate.com. See →.

Ibid.

Noah Shachtman, “‘Human Terrain’ Chief Ousted,” June 15, 2010, wired.com. See →.

Pelton, “Afghanistan: The New War for Hearts and Minds,”Men’s Journal (Feb. 2009). See →.