Is the internet dead?1 This is not a metaphorical question. It does not suggest that the internet is dysfunctional, useless or out of fashion. It asks what happened to the internet after it stopped being a possibility. The question is very literally whether it is dead, how it died and whether anyone killed it.

But how could anyone think it could be over? The internet is now more potent than ever. It has not only sparked but fully captured the imagination, attention and productivity of more people than at any other point before. Never before have more people been dependent on, embedded into, surveilled by, and exploited by the web. It seems overwhelming, bedazzling and without immediate alternative. The internet is probably not dead. It has rather gone all-out. Or more precisely: it is all over!

This implies a spatial dimension, but not as one might think. The internet is not everywhere. Even nowadays when networks seem to multiply exponentially, many people have no access to the internet or don’t use it at all. And yet, it is expanding in another direction. It has started moving offline. But how does this work?

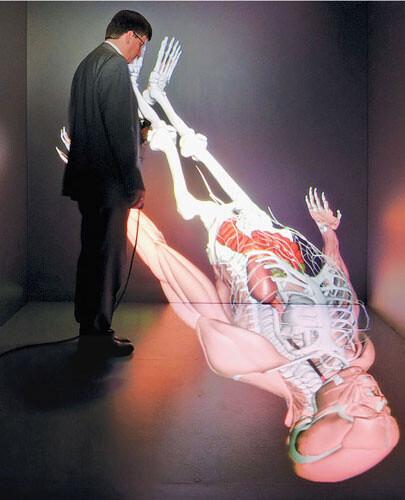

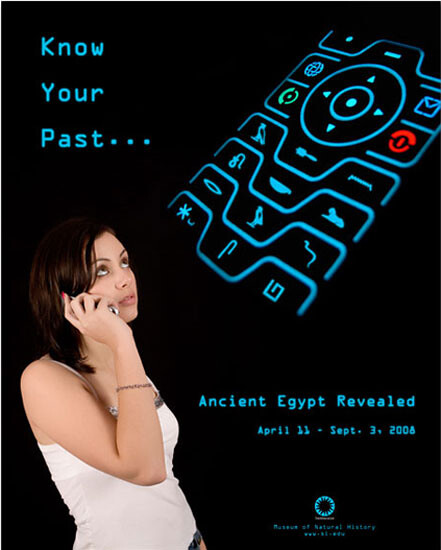

Remember the Romanian uprising in 1989, when protesters invaded TV studios to make history? At that moment, images changed their function.2 Broadcasts from occupied TV studios became active catalysts of events—not records or documents. 3 Since then it has become clear that images are not objective or subjective renditions of a preexisting condition, or merely treacherous appearances. They are rather nodes of energy and matter that migrate across different supports,4 shaping and affecting people, landscapes, politics, and social systems. They acquired an uncanny ability to proliferate, transform, and activate. Around 1989, television images started walking through screens, right into reality.5

This development accelerated when web infrastructure started supplementing TV networks as circuits for image circulation.6 Suddenly, the points of transfer multiplied. Screens were now ubiquitous, not to speak of images themselves, which could be copied and dispersed at the flick of a finger.

Data, sounds, and images are now routinely transitioning beyond screens into a different state of matter.7 They surpass the boundaries of data channels and manifest materially. They incarnate as riots or products, as lens flares, high-rises, or pixelated tanks. Images become unplugged and unhinged and start crowding off-screen space. They invade cities, transforming spaces into sites, and reality into realty. They materialize as junkspace, military invasion, and botched plastic surgery. They spread through and beyond networks, they contract and expand, they stall and stumble, they vie, they vile, they wow and woo.

Just look around you: artificial islands mimic genetically manipulated plants. Dental offices parade as car commercial film sets. Cheekbones are airbrushed just as whole cities pretend to be YouTube CAD tutorials. Artworks are e-mailed to pop up in bank lobbies designed on fighter jet software. Huge cloud storage drives rain down as skylines in desert locations. But by becoming real, most images are substantially altered. They get translated, twisted, bruised, and reconfigured. They change their outlook, entourage, and spin. A nail paint clip turns into an Instagram riot. An upload comes down as shitstorm. An animated GIF materializes as a pop-up airport transit gate. In some places, it seems as if entire NSA system architectures were built—but only after Google-translating them, creating car lofts where one-way mirror windows face inwards. By walking off-screen, images are twisted, dilapidated, incorporated, and reshuffled. They miss their targets, misunderstand their purpose, get shapes and colors wrong. They walk through, fall off, and fade back into screens.

Grace Jones’s 2008 black-and-white video clip “Corporate Cannibal,” described by Steven Shaviro as a pivotal example of post-cinematic affect, is a case in point.8 By now, the nonchalant fluidity and modulation of Jones’s posthuman figure has been implemented as a blueprint for austerity infrastructure. I could swear that Berlin bus schedules are consistently run on this model—endlessly stretching and straining space, time, and human patience. Cinema’s debris rematerializes as investment ruins or secret “Information Dominance Centers.”9 But if cinema has exploded into the world to become partly real, one also has to accept that it actually did explode. And it probably didn’t make it through this explosion either.

Post-Cinema

For a long time, many people have felt that cinema is rather lifeless. Cinema today is above all a stimulus package to buy new televisions, home projector systems, and retina display iPads. It long ago became a platform to sell franchising products—screening feature-length versions of future PlayStation games in sanitized multiplexes. It became a training tool for what Thomas Elsaesser calls the military-industrial-entertainment complex.

Everybody has his or her own version of when and how cinema died, but I personally believe it was hit by shrapnel when, in the course of the Bosnian War, a small cinema in Jajce was destroyed around 1993. This was where the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia was founded during WWII by the Anti-Fascist Council for the National Liberation of Yugoslavia (AVNOJ). I am sure that cinema was hit in many other places and times as well. It was shot, executed, starved, and kidnapped in Lebanon and Algeria, in Chechnya and the DRC, as well as in many other post-Cold War conflicts. It didn’t just withdraw and become unavailable, as Jalal Toufic wrote of artworks after what he calls a surpassing disaster.10 It was killed, or at least it fell into a permanent coma.

But let’s come back to the question we began with. In the past few years many people—basically everybody—have noticed that the internet feels awkward, too. It is obviously completely surveilled, monopolized, and sanitized by common sense, copyright, control, and conformism. It feels as vibrant as a newly multiplexed cinema in the nineties showing endless reruns of Star Wars Episode 1. Was the internet shot by a sniper in Syria, a drone in Pakistan, or a tear gas grenade in Turkey? Is it in a hospital in Port Said with a bullet in its head? Did it commit suicide by jumping out the window of an Information Dominance Center? But there are no windows in this kind of structure. And there are no walls. The internet is not dead. It is undead and it’s everywhere.

The Game of Life is a cellular automaton devised by the British mathematician John Horton Conway in 1970. The “game” is a zero-player game, meaning that its evolution is determined by its initial state, requiring no further input. One interacts with the Game of Life by creating an initial configuration and observing how it evolves.

I Am a Minecraft Redstone Computer

So what does it mean if the internet has moved offline? It crossed the screen, multiplied displays, transcended networks and cables to be at once inert and inevitable. One could imagine shutting down all online access or user activity. We might be unplugged, but this doesn’t mean we’re off the hook. The internet persists offline as a mode of life, surveillance, production, and organization—a form of intense voyeurism coupled with maximum nontransparency. Imagine an internet of things all senselessly “liking” each other, reinforcing the rule of a few quasi-monopolies. A world of privatized knowledge patrolled and defended by rating agencies. Of maximum control coupled with intense conformism, where intelligent cars do grocery shopping until a Hellfire missile comes crashing down. Police come knocking on your door for a download—to arrest you after “identifying” you on YouTube or CCTV. They threaten to jail you for spreading publicly funded knowledge? Or maybe beg you to knock down Twitter to stop an insurgency? Shake their hands and invite them in. They are today’s internet in 4D.

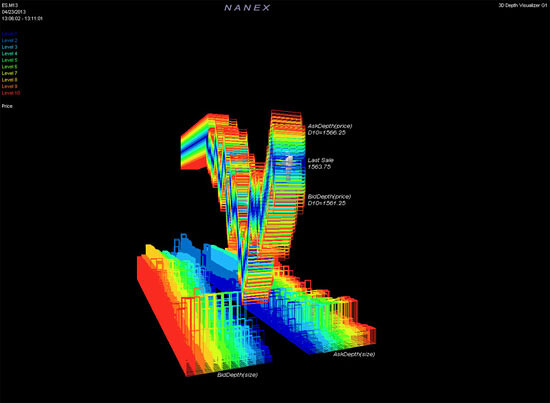

The all-out internet condition is not an interface but an environment. Older media as well as imaged people, imaged structures, and image objects are embedded into networked matter. Networked space is itself a medium, or whatever one might call a medium’s promiscuous, posthumous state today. It is a form of life (and death) that contains, sublates, and archives all previous forms of media. In this fluid media space, images and sounds morph across different bodies and carriers, acquiring more and more glitches and bruises along the way. Moreover, it is not only form that migrates across screens, but also function.11 Computation and connectivity permeate matter and render it as raw material for algorithmic prediction, or potentially also as building blocks for alternate networks. As Minecraft Redstone computers12 are able to use virtual minerals for calculating operations, so is living and dead material increasingly integrated with cloud performance, slowly turning the world into a multilayered motherboard.13

But this space is also a sphere of liquidity, of looming rainstorms and unstable climates. It is the realm of complexity gone haywire, spinning strange feedback loops. A condition partly created by humans but also only partly controlled by them, indifferent to anything but movement, energy, rhythm, and complication. It is the space of the rōnin of old, the masterless samurai freelancers fittingly called wave men and women: floaters in a fleeting world of images, interns in dark net soap lands. We thought it was a plumbing system, so how did this tsunami creep up in my sink? How is this algorithm drying up this rice paddy? And how many workers are desperately clambering on the menacing cloud that hovers in the distance right now, trying to squeeze out a living, groping through a fog which may at any second transform both into an immersive art installation and a demonstration doused in cutting-edge tear gas?

Postproduction

But if images start pouring across screens and invading subject and object matter, the major and quite overlooked consequence is that reality now widely consists of images; or rather, of things, constellations, and processes formerly evident as images. This means one cannot understand reality without understanding cinema, photography, 3D modeling, animation, or other forms of moving or still image. The world is imbued with the shrapnel of former images, as well as images edited, photoshopped, cobbled together from spam and scrap. Reality itself is postproduced and scripted, affect rendered as after-effect. Far from being opposites across an unbridgeable chasm, image and world are in many cases just versions of each other.14 They are not equivalents however, but deficient, excessive, and uneven in relation to each other. And the gap between them gives way to speculation and intense anxiety.

Under these conditions, production morphs into postproduction, meaning the world can be understood but also altered by its tools. The tools of postproduction: editing, color correction, filtering, cutting, and so on are not aimed at achieving representation. They have become means of creation, not only of images but also of the world in their wake. One possible reason: with digital proliferation of all sorts of imagery, suddenly too much world became available. The map, to use the well-known fable by Borges, has not only become equal to the world, but exceeds it by far.15 A vast quantity of images covers the surface of the world—very in the case of aerial imaging—in a confusing stack of layers. The map explodes on a material territory, which is increasingly fragmented and also gets entangled with it: in one instance, Google Maps cartography led to near military conflict.16

While Borges wagered that the map might wither away, Baudrillard speculated that on the contrary, reality was disintegrating.17 In fact, both proliferate and confuse one another: on handheld devices, at checkpoints, and in between edits. Map and territory reach into one another to realize strokes on trackpads as theme parks or apartheid architecture. Image layers get stuck as geological strata while SWAT teams patrol Amazon shopping carts. The point is that no one can deal with this. This extensive and exhausting mess needs to be edited down in real time: filtered, scanned, sorted, and selected—into so many Wikipedia versions, into layered, libidinal, logistical, lopsided geographies.

This assigns a new role to image production, and in consequence also to people who deal with it. Image workers now deal directly in a world made of images, and can do so much faster than previously possible. But production has also become mixed up with circulation to the point of being indistinguishable. The factory/studio/tumblr blur with online shopping, oligarch collections, realty branding, and surveillance architecture. Today’s workplace could turn out to be a rogue algorithm commandeering your hard drive, eyeballs, and dreams. And tomorrow you might have to disco all the way to insanity.

As the web spills over into a different dimension, image production moves way beyond the confines of specialized fields. It becomes mass postproduction in an age of crowd creativity. Today, almost everyone is an artist. We are pitching, phishing, spamming, chain-liking or mansplaining. We are twitching, tweeting, and toasting as some form of solo relational art, high on dual processing and a smartphone flat rate. Image circulation today works by pimping pixels in orbit via strategic sharing of wacky, neo-tribal, and mostly US-American content. Improbable objects, celebrity cat GIFs, and a jumble of unseen anonymous images proliferate and waft through human bodies via Wi-Fi. One could perhaps think of the results as a new and vital form of folk art, that is if one is prepared to completely overhaul one’s definition of folk as well as art. A new form of storytelling using emojis and tweeted rape threats is both creating and tearing apart communities loosely linked by shared attention deficit.

Circulationism

But these things are not as new as they seem. What the Soviet avant-garde of the twentieth century called productivism—the claim that art should enter production and the factory—could now be replaced by circulationism. Circulationism is not about the art of making an image, but of postproducing, launching, and accelerating it. It is about the public relations of images across social networks, about advertisement and alienation, and about being as suavely vacuous as possible.

But remember how productivists Mayakovsky and Rodchenko created billboards for NEP sweets? Communists eagerly engaging with commodity fetishism?18 Crucially, circulationism, if reinvented, could also be about short-circuiting existing networks, circumventing and bypassing corporate friendship and hardware monopolies. It could become the art of recoding or rewiring the system by exposing state scopophilia, capital compliance, and wholesale surveillance. Of course, it might also just go as wrong as its predecessor, by aligning itself with a Stalinist cult of productivity, acceleration, and heroic exhaustion. Historic productivism was—let’s face it—totally ineffective and defeated by an overwhelming bureaucratic apparatus of surveillance/workfare early on. And it is quite likely that circulationism—instead of restructuring circulation—will just end up as ornament to an internet that looks increasingly like a mall filled with nothing but Starbucks franchises personally managed by Joseph Stalin.

Will circulationism alter reality’s hard- and software; its affects, drives, and processes? While productivism left few traces in a dictatorship sustained by the cult of labor, could circulationism change a condition in which eyeballs, sleeplessness, and exposure are an algorithmic factory? Are circulationism’s Stakhanovites working in Bangladeshi like-farms,19or mining virtual gold in Chinese prison camps,20 churning out corporate consent on digital conveyor belts?

Open Access

But here is the ultimate consequence of the internet moving offline.21 If images can be shared and circulated, why can’t everything else be too? If data moves across screens, so can its material incarnations move across shop windows and other enclosures. If copyright can be dodged and called into question, why can’t private property? If one can share a restaurant dish JPEG on Facebook, why not the real meal? Why not apply fair use to space, parks, and swimming pools?22 Why only claim open access to JSTOR and not MIT—or any school, hospital, or university for that matter? Why shouldn’t data clouds discharge as storming supermarkets?23 Why not open-source water, energy, and Dom Pérignon champagne?

If circulationism is to mean anything, it has to move into the world of offline distribution, of 3D dissemination of resources, of music, land, and inspiration. Why not slowly withdraw from an undead internet to build a few others next to it?

This is what the term “post-internet,” coined a few years ago by Marisa Olson and subsequently Gene McHugh, seemed to suggest while it had undeniable use value as opposed to being left with the increasingly privatised exchange value it has at this moment.

Cf. Peter Weibel, “Medien als Maske: Videokratie,” in Von der Bürokratie zur Telekratie. Rumänien im Fernsehen, ed. Keiko Sei (Berlin: Merve, 1990), 124–149, 134f.

Cătălin Gheorghe, “The Juridical Rewriting of History,” in Trial/Proces, ed. Cătălin Gheorghe (Iaşi: Universitatea de Arte “George Enescu” Iaşi, 2012), 2–4. See →.

Ceci Moss and Tim Steer in a stunning exhibition announcement: “The object that exists in motion spans different points, relations and existences but always remains the same thing. Like the digital file, the bootlegged copy, the icon, or Capital, it reproduces, travels and accelerates, constantly negotiating the different supports that enable its movement. As it occupies these different spaces and forms it is always reconstituting itself. It doesn’t have an autonomous singular existence; it is only ever activated within the network of nodes and channels of transportation. Both a distributed process and an independent occurrence, it is like an expanded object ceaselessly circulating, assembling and dispersing. To stop it would mean to break the whole process, infrastructure or chain that propagates and reproduces it.” See →.

One instance of a wider political phenomena called transition. Coined for political situations in Latin America and then applied to Eastern European contexts after 1989, this notion described a teleological process consisting of an impossible catch-up of countries “belatedly” trying to achieve democracy and free-market economies. Transition implies a continuous morphing process, which in theory would make any place ultimately look like the ego ideal of any default Western nation. As a result, whole regions were subjected to radical makeovers. In practice, transition usually meant rampant expropriation coupled with a radical decrease in life expectancy. In transition, a bright neoliberal future marched off the screen to be realized as a lack of health care coupled with personal bankruptcy, while Western banks and insurance companies not only privatized pensions, but also reinvested them in contemporary art collections. See →.

Images migrating across different supports are of course nothing new. This process has been apparent in art-making since the Stone Age. But the ease with which many images morph into the third dimension is a far cry from ages when a sketch had to be carved into marble manually. In the age of postproduction, almost everything made has been created by means of one or more images, and any IKEA table is copied and pasted rather than mounted or built.

See Steven Shaviro’s wonderful analysis in “Post-Cinematic Affect: On Grace Jones, Boarding Gate and Southland Tales,”Film-Philosophy 14.1 (2010): 1–102. See also his book Post-Cinematic Affect (London: Zero Books, 2010).

Greg Allen, “The Enterprise School,” Greg.org, Sept. 13, 2013. See →.

Jalal Toufic, The Withdrawal of Tradition Past a Surpassing Catastrophe (2009). See →.

“The Cloud, the State, and the Stack: Metahaven in Conversation with Benjamin Bratton.” See →.

Thanks to Josh Crowe for drawing my attention to this.

“The Cloud, the State, and the Stack.”

Oliver Laric, “Versions,” 2012. See →.

Jorge Luis Borges, “On Exactitude in Science,” in Collected Fictions, trans. Andrew Hurley (New York: Penguin, 1999): 75–82. “‘In that Empire, the Art of Cartography attained such Perfection that the map of a single Province occupied the entirety of a City, and the map of the Empire, the entirety of a Province. In time, those Unconscionable Maps no longer satisfied, and the Cartographers Guilds struck a Map of the Empire whose size was that of the Empire, and which coincided point for point with it. The following Generations, who were not so fond of the Study of Cartography as their Forebears had been, saw that that vast Map was Useless, and not without some Pitilessness was it, that they delivered it up to the Inclemencies of Sun and Winters. In the Deserts of the West, still today, there are Tattered Ruins of that Map, inhabited by Animals and Beggars; in all the Land there is no other Relic of the Disciplines of Geography.’ Suárez Miranda, Viajes de varones prudentes, Libro IV, Cap. XLV, Lérida, 1658.”

L. Arlas, “Verbal spat between Costa Rica, Nicaragua continues,” Tico Times, Sept. 20, 2013. See →. Thanks to Kevan Jenson for mentioning this to me.

Jean Baudrillard, “Simulacra and Simulations,” in Jean Baudrillard: Selected Writings, ed. Mark Poster (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1988): 166–184.

Christina Kiaer, “‘Into Production!’: The Socialist Objects of Russian Constructivism,” Transversal (Sept. 2010). See →. “Mayakovsky’s advertising jingles address working-class Soviet consumers directly and without irony; for example, an ad for one of the products of Mossel’prom, the state agricultural trust, reads: ‘Cooking oil. Attention working masses. Three times cheaper than butter! More nutritious than other oils! Nowhere else but Mossel’prom.’ It is not surprising that Constructivist advertisements would speak in a pro-Bolshevik, anti-NEP-business language, yet the picture of the Reklam-Konstruktoradvertising business is more complicated. Many of their commercial graphics move beyond this straightforward language of class difference and utilitarian need to offer a theory of the socialist object. In contrast to Brik’s claim that in this kind of work they are merely ‘biding their time,’ I propose that their advertisements attempt to work out the relation between the material cultures of the prerevolutionary past, the NEP present and the socialist novyi byt of the future with theoretical rigor. They confront the question that arises out of the theory of Boris Arvatov: What happens to the individual fantasies and desires organized under capitalism by the commodity fetish and the market, after the revolution?”

Charles Arthur, “How low-paid workers at ‘click farms’ create appearance of online popularity,” The Guardian, Aug. 2, 2013. See →.

Harry Sanderson, “Human Resolution,” Mute, April 4, 2013. See →.

And it is absolutely not getting stuck with data-derived sculptures exhibited in white cube galleries.

“Spanish workers occupy a Duke’s estate and turn it into a farm,” Libcom.org, Aug. 24, 2012. See →. “Earlier this week in Andalusia, hundreds of unemployed farmworkers broke through a fence that surrounded an estate owned by the Duke of Segorbe, and claimed it as their own. This is the latest in a series of farm occupations across the region within the last month. Their aim is to create a communal agricultural project, similar to other occupied farms, in order to breathe new life into a region that has an unemployment rate of over 40 percent. Addressing the occupiers, Diego Canamero, a member of the Andalusian Union of Workers, said that: ‘We’re here to denounce a social class who leave such a place to waste.’ The lavish well-kept gardens, house, and pool are left empty, as the Duke lives in Seville, more than 60 miles away.”

Thomas J. Michalak, “Mayor in Spain leads food raids for the people,” Workers.org, Aug. 25, 2012. See →. “In the small Spanish town of Marinaleda, located in the southern region of Andalusía, Mayor Juan Manuel Sánchez Gordillo has an answer for the country’s economic crisis and the hunger that comes with it: He organized and led the town’s residents to raid supermarkets to get the food necessary to survive.” See also →.

This text comes from nearly two years of testing versions of it in front of hundreds of people. So thanks to all of you, but mostly to my students, who had to endure most of its live writing. Some parts of this argument were formed in a seminar organized by Janus Hom and Martin Reynolds, but also in events run by Andrea Phillips and Daniel Rourke, Michael Connor, Shumon Basar, Christopher Kulendran Thomas, Brad Troemel, and exchanges with Jesse Darling, Linda Stupart, Karen Archey, and many others. I am taking cues from texts by Redhack, James Bridle, Boris Groys, Jörg Heiser, David Joselit, Christina Kiaer, Metahaven, Trevor Paglen, Brian Kuan Wood, and many works by Laura Poitras. But the most important theoretical contribution to shape this text was my collaborator Leon Kahane’s attempt to shoplift a bottle of wine for a brainstorming session.