I have no desire to disparage American art, which is a child, and therefore merits being loved and protected.

—Andre Villebeuf in Gringorie, Paris

Those who have been to the United States bring back nothing from visiting American museums but memories of Italian and French works found there.

—Lucie Mazauric in Vendredi, Paris

Critic Clement Greenberg tells the story of American avant-garde art in the years since World War II—a time when New York school painting and vital sculpture made Western Europe turn at last to the United States for inspiration.

—Subhead of the article “America Takes the Lead: 1945–1965” by Clement Greenberg, Art in America, August–September 1965

When the first comprehensive exhibition of American art abroad, titled “Trois Siecles d’Art aux États-Unis” and organized by the Museum of Modern Art, opened at the Musée de Jeu de Paume in 1939, many Parisians were surprised to find out that there was such a thing as “American art.” Similarly, many well-intentioned art critics at the time expressed sympathy for the youthful attempts of American painters to emulate their French colleagues. Only a quarter of a century later, a leading American art critic felt confident enough to declare that it was now time for Europeans to look to Americans for inspiration.

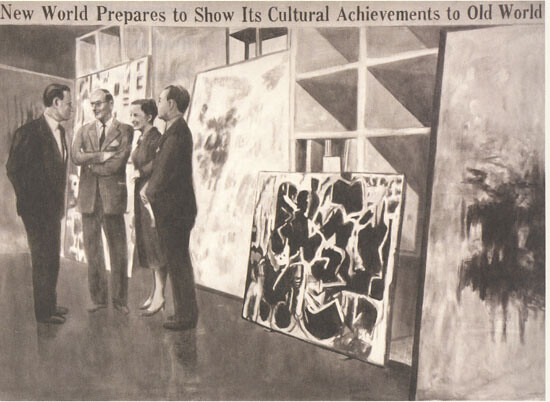

There are probably different ways to explain the dramatic rise of American art, which became apparent to Europeans a bit earlier than to Americans. While in 1958 the New York Times published the timid headline “New World Prepares to Show Its Cultural Achievements to Old World,” the London Horizon, fully aware of the change that was taking place, had a bolder take: “The New American Painting Captures Europe.”

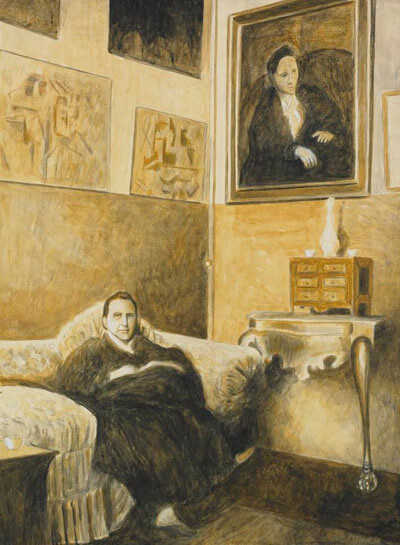

One possible approach to telling this story would be to trace what could be called the “American interpretation of European modern art” through various exhibitions and collections organized by American curators and art lovers. The earliest and most influential collection was the one assembled by Gertrude and Leo Stein in Paris, exhibited on the walls of their salon in the beginning of the twentieth century.

This was perhaps the first time (around 1905) that paintings by Cezanne, Matisse, and Picasso were exhibited together. Not only the Steins’s Parisian friends, but also many of their art-loving compatriots from America visited the salon, saw the collection, and spread the word about it back home. One of them, Alfred Stieglitz, was the first to exhibit the works of Cezanne and Matisse in New York, at his Gallery 291 in 1910. Then a couple of years later, the Steins lent their Blue Nude by Matisse to the Armory Show.

The Armory Show—officially titled the International Exhibition of Modern Art—represented another early encounter between Americans and European modern art. This was more spectacular than any previous encounter, since it was held on domestic soil and reached a broader audience. It was organized and curated by the members of the Association of American Painters and Sculptors, whose intention was to “[give] the public here the opportunity to see for themselves the results of new influences at work in other countries in an art way.” They further stated that

The foreign paintings and sculptures here shown are regarded by the committee of the Association as expressive of the forces which have been at work abroad of late, forces which cannot be ignored because they have had results. The American artists responsible for bringing the works of foreigners to this country consider the exhibition as of equal importance for themselves as for the lay public. The less they find their work showing signs of the developments indicated in the Europeans, the more reason they will have to consider whether or not painters or sculptors here have fallen behind through escaping the incidence through distance and for other reasons of the forces that have manifested themselves on the other side of the Atlantic.

Since the members of the Association clearly felt that Americans lagged behind recent developments in Europe, they wanted to shake up the domestic scene by bringing to New York the most avant-garde works available. The subtitle of the exhibition—“American & Foreign Art”—was displayed in the exhibition hall but did not appear on the cover of the catalogue. Furthermore, in the catalogue the artists were not listed according to their nationality, as was customary at the time, but only by their names. Thus, on two facing pages one found Braque, Kirchner, Kandinsky, Cezanne, Hartley, Duchamp, and Munch listed together. At the opening speech of the Armory Show, John Quinn, a member of the Association and a prominent collector of modern art, stated that “the Association felt that it was time the American people had an opportunity to see and judge for themselves concerning the work of Europeans who are creating a new art.”

The impact of the Armory Show on the American art scene was huge. Its ripple effects would be felt for decades to come. Many European works on display at the show were acquired by local collectors and thus continued to have an impact on the American art scene after the show closed. One of the most important collections of modern art on either side of the Atlantic—that of Walter and Louise Arensberg—was initiated by the Armory Show. The Arensbergs’s apartment became a gathering place for emerging New York “art internationale” artists, including Marcel Duchamp, whose Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2) became the emblem of the avant-garde. It was Duchamp, together with Katherine Dreier, an artist and collector who also participated in the Armory Show, who “had the courage to incorporate this Museum of Modern Art as the Société Anonyme.” A report issued by the Société regarding its exhibition schedule of 1920–21 emphasized that “The Société Anonyme, Inc., was also the only [American art venue] which was truly international, exhibiting during the winter the works of men representing ten different countries.” In addition to the nationality of the artist, the following “Schools of Modern Art” were also listed in the report: Post-Impressionist, Pre-Cubist, Cubist, Expressionist, Simultaneist, Futurist, Dadaist, and “Those Belonging to No Schools, But Imbued with the New Spirit in Art.”

Thirteen years after the Armory Show, the Société Anonyme assembled the second International Exhibition of Modern Art, this time at the Brooklyn Museum. In the exhibition catalogue, the artists were grouped by their nationality, representing twenty countries including the US. For some of the artists, it was perhaps their first time exhibiting in America: Arp, Max Ernst, Léger, Schwitters, Mondrian, Moholy-Nagy, de Chirico, Klee, Lissitzky, Miro, and Man Ray. (Malevich was shown in the Société Anonyme’s “Modern Art” collection at the Sesqui-Centenial International Exhibition, held in Philadelphia in 1926). In a press release for the Brooklyn Museum show, the Société Anonyme was described as

an international organization for the promotion of the study of the experimental in art for students in America [that] renders aid to conserve the vigor and vitality of the new expression of beauty in the art of today … When one considers that the gathering together of all these works has been done out of love, one realizes the vigor and vitality of the Modern art Movement.

This exhibition and the activities of the Société Anonime represented one of the most important developments in the New York art scene of the 1920s, especially in introducing the latest European avant-garde art to American artists, art professionals, and the general public. The exhibition was perhaps the first museum of modern art, not only by name but by collection as well. The only thing missing was a story that would connect the various works of twentieth-century modern art in a coherent historical narrative. It took another decade and another modern museum for this to happen.

Torpedo in Time

During the spring [of 1929] a small group of people got together and took a first step toward a museum of modern art in New York.

—Abby Aldrich Rockefeller

Besides Abby Rockefeller, in the nucleus of the group that established MoMA were Lillie P. Bliss and Mary Quinn Sullivan. All three were well-known collectors and art lovers. Alfred H. Barr, Jr., a twenty-seven-year-old Princeton and Harvard student of art history, was selected to be the first director. He had recently returned from a long journey through Europe, including Moscow, where he stayed for two months and met some key protagonists of the Soviet avant-garde—Tatlin, Lissitzky, Rodchenko, and Eisenstein. One August day in 1929 there appeared an untitled and undated public announcement:

The belief that New York needs a Museum of Modern Art scarcely requires apology. All over the world the rising tide of interest in the modern movement has found expression not only in private collections but also in the formation of great public galleries for the specific purpose of exhibiting permanent as well as temporary collections of modern art. That New York has no such gallery is an extraordinary anachronism … The Luxembourg [museum] for instance exhibits most of the French national accumulation of modern art, a collection which is in continual transformation. Theoretically all works of art in the Luxembourg are tentatively exhibited. Ten years after the artists [sic] death they may go to the Louvre, they may be relegated to provincial galleries or they may be forgotten in storage … In Berlin similarly the historical museums are supplemented by the National Galerie in the Kronprinzen Palast. Here Picasso, Derain, Matisse rub shoulders with Klee, Nolde, Dix, Feininger, and the best of the modern Germans … Paradoxically New York, if fully awakened, would be able in a very few years to create a public collection of modern art which would place her as far ahead of Paris, Berlin, London as she is at present behind them. This museum of modern art would in no way conflict with the Metropolitan but would seek rather to establish a relationship to it like that of the Luxembourg to the Louvre.

Indeed, later that year, MoMA opened in a five-room rented space with an “historical” exhibition of (European) Post-Impressionist art, titled “The First Loan Exhibition: Cezanne, Gauguin, Seurat, Van Gogh.” This was followed by the more contemporary exhibitions “Paintings by Nineteen Living Americans” and “Painting in Paris, from American Collections.” For the next few years this young museum would be a museum in name only, since it didn’t have its own collection and operated more like a gallery, staging temporary exhibitions with artworks loaned from various private collectors. In some cases, visitors could even buy the works exhibited at the show. On top of all that, the name of the museum was an oxymoron, as Gertrude Stein once told Barr: “I do not understand how it can be both, museum and modern?”

The museum’s first collection came as a bequest from one of its “founding mothers,” Lillie P. Bliss, consisting almost entirely of European Post-Impressionist and modern artists. The bequest included numerous Cezannes (among them The Bather), a few Seurats, Gauguins, Matisses, Derains, and Picassos. It featured only two works by Americans (Davies and Kuhn), anticipating the nature of the museum’s collection in its first two decades—predominantly “European-International,” with sprinkles of Americans.

Meanwhile, the idea of “tentativeness” and of the “continual transformation of the collection” was articulated in a diagram called the “Torpedo in Time.” According to this diagram, the museum would be like a fifty-year-long tube that “travels through time.” As time passed, new works would enter the mouth of the tube, which represented the “now,” while works older than fifty years from “now” would exit the back of the tube. If the works passed the “test of time,” they would be transferred to the Met. In this sense, MoMA was like Purgatory and the Met was like Paradise. (No solution was offered for those works that didn’t pass the test.) Conceptually, a museum of this kind would, on the one hand, eliminate the need to accumulate artworks; on the other hand, it would be, in historical terms, an institution with a short-term memory. One perennial problem faced by museums that have a timeline open to the future is selection. Even within the short-term memory of a museum like MoMA, the institution can collect and display only a limited number of artifacts from the present, forcing it to decide today which aspects of the present will become the past, which will be preserved (remembered) for the future. How can anyone today know (or be able to decide) what of the present will be important to people fifty years from now?

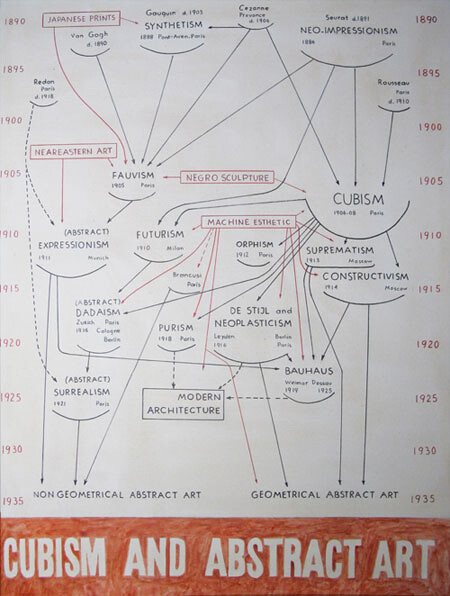

But recollection always happens retroactively—not by anticipating the future, but by interpreting the past. And this is exactly what happened in 1936 at the exhibition “Cubism and Abstract Art,” perhaps the most important exhibition of the twentieth century. On the cover of the catalogue for the exhibition was Alfred Barr’s “genealogical tree,” which represented in graphical form the historicization of the four previous decades of European modern art.

According to Barr’s genealogical tree, the story of modern art began with Post-Impressionism (Cezanne) and branched in two directions, one towards Fauvism (Matisse), Expressionism, and Non-Geometrical Abstract Art, and the other towards Cubism (Picasso), Suprematism, Constructivism, Neo-Plasticism, and Geometric Abstract Art. Organized chronologically and by “international movements,” Barr’s genealogical tree was a radical departure from the concept of “national schools” which dominated European art historiography and which was embodied in the most prestigious art event of the time, the Venice Biennale. In addition to painting and sculpture, “Cubism and Abstract Art” included categories such as construction, photography, architecture, industrial art, theatre, film, poster art, and typography, thus introducing an expanded notion of the “artwork” into a museum context. The Russian/Soviet avant-garde, one of the most important cultural developments in Europe, was extensively represented at the exhibition. It was historicized as an integral part of this new “international narrative” of modern art, at a time when its achievements had been removed from public view, both in the Soviet Union and the rest of Europe. It is thanks to this exhibition that the works of Malevich, Tatlin, Lissitzky, Stepanova, Popova, Rodchenko, and Goncharova are so well-known and respected today. Finally, as a footnote, it should be remembered that one of the emblems of modern art, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, was not only represented in a museum context for the first time at this exhibition (and not even as an original, but as a small reproduction). It was also this exhibition that placed Demoiselles at the beginning of the story of modern art, where it has remained ever since.

Both the exhibition and the diagram provided the direction for the subsequent expansion of the MoMA collection. The concept of the “Torpedo in Time” was discretely abandoned, although it took almost two decades for this to be formally announced (“Important Change in Policy,” 1953 MoMA Bulletin). The museum was no longer a solid tube freely moving through time. Instead, it became an elastic tube that kept on stretching with time, having one end (the beginning) fixed in the 1900s, and the other in an ever-moving present. This concept of the museum—with one end fixed in a moment in the past and the other open toward the future—would resolve problems on the memory side, while it exacerbated problems on the accumulation and selection side, making the model unsustainable in the long run.

The exhibition “Cubism and Abstract Art” was followed by “Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism,” thus completing the historicization of all modern art movements until the mid-1930s. This historicization of European art by an American (Barr) was almost entirely based on artifacts brought from overseas and then assembled and interpreted by someone from another culture. At that moment in its history, MoMA could be thought of as not only an art museum, but as an ethnographic museum as well. In this MoMA narrative, avant-garde-centered modern art was almost entirely a European phenomenon, with Paris as its capital and Picasso as its most important practicioner.

All this took place at a time when modern art was disappearing throughout Europe. The cosmopolitanism of the avant-garde was the antithesis to the rising nationalism that swept through Europe in the 1930s, leading to war and carnage. Modern art was completely marginalized and removed from museums as “bourgeois and formalistic” in the Soviet Union, and “degenerate, Jewish, and Bolshevik” in Germany. In France meanwhile, modern art was ironically never included in museums in the first place. In the US, most of the public and the political establishment were not in love with modern art, but since art was not a government matter, MoMA, as a private corporation, could exhibit and promote its program freely, without state interference. This is why the American public could see European modern art at a time when there was no modern art in Europe. MoMA became a kind of Noah’s Arc of modern art.

While walking through MoMA, a majority of the American museumgoers there probably had no idea that what they were seeing was not Europe’s present, but its past. Although all the artworks were from Europe, hardly anyone was aware that the story told through the arrangement of the museum’s exhibits was not European; it was not a European interpretation of modern art. Instead, it was a story told by an American—namely, Alfred Barr. This story did not merely preserve the memory of European modern art, but in fact reinvented it by categorizing artists according to “international movements” instead of “national schools.” After the catastrophe of WWII, MoMA began to be perceived in Europe as the most important museum of modern art in the world. By admiring this American museum with the most comprehensive collection of European modern art around, “natives” of the Old World were unaware that they adopted its story as well—its story about their own art and culture. Gradually, this story became the dominant, canonical narrative on both sides of the Atlantic, determining future developments in Western art for decades to come.

An early attempt to establish a postwar modern art narrative in Europe, with artists represented individually rather than by nations, was made in Paris in 1952 with an exhibition titled “Twentieth Century Masterpieces,” organized by the Congress for Cultural Freedom. The Congress was an “international association of intellectuals—writers, philosophers, painters, musicians, artists, and scientists—whose aim [was] to promote the freedom of creative man.” The exhibition took place at the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris and at the Tate Gallery in London. The works that appeared in the show were selected by James Johnson Sweeney. With the exception of Alexander Calder, the exhibition did not include any American artists, but instead presented European artists such as Malevich, Duchamp, Kandinsky, Max Ernst, Delaunay, Kokoschka, Kirchner, and Miro. The works in the show were mostly borrowed from American museums and collections.

The only place that resisted this new narrative of modern art was a museum in the metropolis of modernism—Paris. The 1954 guide-catalogue of the Musée National d’Art Moderne includes a floor plan with thirty-eight rooms spread across three floors. Thirty-seven of these rooms were entirely devoted to Parisian art of the previous five decades. One tiny room (No. 31) was intended for Écoles Étrangères (Foreign Schools). Furthermore, among the artists listed in the museum collection, the following names were nowhere to be found: Mondrian, Malevich, Magritte, Duchamp, Man Ray, Tatlin, Lissitzky, Stepanova, Popova, Rodchenko, Schwitters, Marc, Kirchner, Nolde, Boccioni, Moholy-Nagy, van Doesburg, Archipenko, Feininger, Gabo … What did the story of twentieth-century modern art look like at the Musée d’Art Moderne without these artists?

The Cosmopolitan Variety

Back in New York, American artists who visited MoMA must have been captivated by the achievements of the Old World. To walk through the galleries and see all of those masterpieces by Matisse, Picasso, Malevich, Mondrian, and Duchamp, while absorbing the story of modern art, must have been a fascinating experience. Perhaps some of these artists, with uneasiness and sadness, also became aware that there was no place for Americans in that story. Although MoMA’s second exhibition was titled “Nineteen Living Americans,” the museum was often criticized for ignoring domestic art. Thus, the introduction to the MoMA Bulletin of 1940, titled “American Art and the Museum,” states:

The Museum of Modern Art has always been deeply concerned with American art, but the Museum was founded upon the principle that art should have no boundaries, that paintings and motion pictures, furniture and sculpture from any country in the world should be shown in the Museum provided they were of superior quality as works of art. This principle is of course in diametric opposition to the hysterically intolerant nationalism which has swept over half of Europe destroying the freedom of art along with the freedom of speech and religion. Nevertheless the Museum has at times been criticized for concerning itself overmuch with the art of foreigners, particularly foreigners who have produced disturbingly new forms, new kinds of pictures or architecture. It is a purpose of this number of the Bulletin not so much to answer these occasional criticisms as to present to the members a report of the extent and variety of what the Museum has done in the field of American art.

However, the real change in MoMA’s relationship to American art began a few years later with the 1946 exhibition “Fourteen Americans,” which included work by Arshile Gorky, Robert Motherwell, and Mark Tobey. This was the first in a series of exhibitions focusing on American art that Dorothy C. Miller would curate for MoMA over the following few of decades. The next in the series, the 1952 exhibition “Fifteen Americans,” brought together artists such as William Baziotes, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Clyfford Still, and Bradley Walker Tomlin. Two years later, “Twelve Americans” introduced James Brooks, Sam Francis, Fritz Glarner, Philip Guston, Grace Hartigan, and Franz Kline, among others.

These are the same artists that formed the core of three traveling exhibitions organized by the MoMA International Program in the 1950s. These exhibitions introduced Europe to a brand of American modern art known as “Abstract Expressionism.” The first in the series, titled “Twelve Contemporary American Painters and Sculptors” (1953–54), was curated by Andrew Carnduff Ritchie and included a wide range of artists, from John Marin, Stuart Davis, Ben Shan, and Edward Hopper to Archile Gorky and Jackson Pollock. It traveled to Paris, Zurich, Düsseldorf, Stockholm, Helsinki, and Oslo. The next exhibition in the series, “Modern Art in the USA (From the Collection of MoMA)” (1955–56), showed fifty years of American modern art, including paintings, sculptures, prints, photography, and architecture. The painting section, curated by Dorothy C. Miller, covered a broad range of American art and was divided into five historical and stylistic sections: 1. Modern Painters—First Generation; 2. Realist Tradition; 3. Romantic Painters; 4. Contemporary Abstract Painting; 5. Modern Primitives. The exhibition traveled to Paris, Zurich, Barcelona, Frankfurt, London, The Hague, Vienna, and Belgrade. A critic for the Spectator began his review of the show by saying, “To read the names in the catalogue of the modern American art exhibition at the Tate with their German, Scandinavian, Netherlandish, Mediterranean, Jewish alliances is to realize the first condition of American art—its cosmopolitan variety.”

The same multi-cultural character of Americans was noticed in Paris as well, but there it was used to question the very existence of such a thing as American art and Americans, since “those are all immigrants or sons of immigrants.” Nevertheless, it seems that of all the MoMA exhibitions, this one had the greatest impact on the general public and art professionals, especially its section “Contemporary Abstract Painting.” For the first time, Europeans had a chance to see paintings by Gorky, Guston, Hartigan, Kline, de Kooning, Motherwell, Pollock, Rothko, Still, and Tomlin displayed together in the same exhibition. Those large, raw, gestural, seemingly unfinished canvases represented a radical departure from the European tradition and aesthetic of easel painting. It became clear that Americans were bringing something new— something unseen before in European museums. From the European perspective, it was with this exhibition that the Americans arrived. Since all these paintings were from the MoMA collection, some European museums even begun to consider including American art in their collections too.

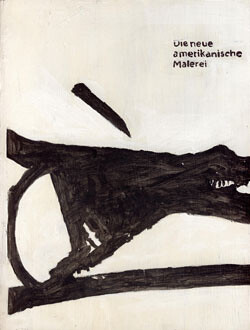

The third and last exhibition in this series, “The New American Painting” curated by Dorothy C. Miller, brought together exclusively abstract artists, with an emphasis on the “Expressionists.” From April 1958 until March 1959, this spectacle of abstract art was on display in Basel, Milan, Madrid, Berlin, Amsterdam, Brussels, Paris, and London. After it returned home, it was presented to the New York public at MoMA. This memorable exhibition confirmed to Europeans what was already apparent: the “new painting” coming from America could no longer be ignored.

The arrival of American painting would eventually be reinforced by Documenta 2 in 1959—but only after the inaugural Documenta, held in Kassel in 1955, ignored it entirely. Entitled “The Art of the Twentieth Century—International Exhibition,” Documenta 1 was primarily intended to reestablish in Europe’s memory the modern art lost in the previous decades, and to connect it to postwar abstract art. The exhibits were organized not by country (like at the Venice Biennale), but with each artist represented individually. For some reason, however, this international exhibition had no place for the Russian/Soviet avant-garde, or for recent American abstract art. In this version of modern art history, there was no Malevich, Tatlin, Rodchenko, or Lissitzky, no Pollock, Kline, de Kooning, Motherwell, or Rothko. Even Brancusi, Duchamp, and Moholy-Nagy were missing. While this narrative based on individualism and internationalism was an obvious improvement over the traditional nation-based narrative of modern art, it was still not Alfred Barr’s story, not yet.

Thus, at Documenta 2, under the auspices of the MoMA International Program, the entire roster from the “The New American Painting” exhibition appeared, enlarged with Helen Frankenthaler, Hans Hofmann, Joan Mitchell, and Robert Rauschenberg. The impact of these artists’ presence at the exhibition was so profound that Documenta 2 later became known as “American.” Americans thus became part of the dominant narrative of modern art, which was, thanks to Barr, rooted in the achievements of the European avant-garde. While the inclusion of American art in this narrative may have been unsurprising (since it was Barr himself who invented the narrative), it was perhaps more surprising that MoMA played a decisive role in preserving the memory of Russian/Soviet avant-garde, which otherwise would have been completely forgotten. New York did not steal the idea of modern art, as some claimed. New York in fact re-remembered and reinvented it.

Clandestine Modernism

Much has been written about these MoMA exhibitions of American art in European museums, which took place during the long standoff between American-led Western Europe and the Soviet Union. It is widely accepted that these exhibitions were secretly financed by US government agencies, including the CIA, as a part of a cultural propaganda campaign aimed at promoting “freedom and democracy” and undermining the Soviet bloc. It is important and necessary to study those aspects of the traveling MoMA exhibitions that relate to the Cold War context, and to determine the nature of the US government’s involvement. First of all, if there was any secret government funding going to these exhibitions (including from the CIA), from whom was this support being hidden? The Soviet Union? As far as the Soviet Union was concerned, these MoMA exhibitions could only be US government propaganda, regardless of whether they were funded by the US government or not. From European allies then? Since it is customary in Europe for the entire domain of art (museums, galleries, art schools and academies, national exhibitions abroad) to be financed by the state, primarily through ministries of culture, these MoMA exhibitions were already perceived as government-sponsored representations of American art. For most Europeans, especially in those days, the idea that museums like the Met and MoMA were private institutions that organized privately funded national exhibitions abroad was completely unheard-of.

If, as far as the Soviets and West Europeans were concerned, it was unnecessary to conceal the fact that the US government funded these exhibitons, then from whom was this support hidden? The only logical answer is: from the US government. Since US taxpayer money cannot in principle be used to support controversial art, if one government agency—let’s say the State Department—decided to facilitate art events abroad, it would most likely try to hide it from other branches of government—for example, from Congress. The case of the 1946 exhibition “Advancing American Art,” organized by the State Department with the intention of sending it abroad to improve America’s image, is very telling. Instead of borrowing the artworks from private collections, someone in the State Department calculated that it would be much cheaper to acquire the collection—using taxpayer money, naturally. When the collection was finally formed, it was stylistically very broad, but no Abstract Expressionist artists were included. Even this kind of collection was so controversial that Congress eventually organized hearings to investigate the possibility that the State Department was supporting leftist, even communist, artists. Soon after, the entire collection was sold as government surplus.

A few years later, in 1952, Alfred Barr publish an article titled “Is Modern Art Communistic?” in which he sought to defend freedom of expression at the time of the Red Scare. In the article, Barr compared recent statements on modern art made by American presidents to similar statements made by Hitler and Stalin. It is within this political climate that MoMA launched, in 1952, its International Program, which was supported by the Rockefeller Brothers Fund. This is the program that would organize the groundbreaking series of exhibitions of American art that toured Europe. The positive effect of these exhibitions in improving America’s image abroad must have been noticed by the US government. The 1956 exhibition “Modern Art in the USA,” which came to Belgrade—the only socialist capital to host a MoMA show during the Cold War—was initiated by the local office of the United States Information Service (USIS), a government agency whose mission was “to understand, inform and influence foreign publics in promotion of the national interest.” Belgrade was not originally on the exhibition itinerary, which is probably why the USIS office, rather than MoMA, organized the exhibition there. In addition to paying to transport the exhibition from Vienna, the USIS paid for insurance and for the exhibition catalogue, while the Yugoslav government paid all local expenses associated with organizing the exhibition at three sites in Belgrade. Finally, we should also remember that in 1959, at the height of the Cold War, the US government–sponsored “American National Exhibition” was held under Buckminster Fuller’s dome in Moscow. Thousands of Soviet citizens had a chance to see paintings by Gorky, Guston, de Koonong, Motherwell, Pollock, and Rothko, among other American artistic achievements.

Regardless of how these MoMA exhibitions came about, we must acknowledge, from the perspective of today, that they played a decisive role in establishing a postwar European cultural identity based on internationalism, individualism, and modernism. Without these values, it would be hard to imagine the emergence of today’s Europe. The exhibitions also helped cement Alfred Barr’s story of modern art, constructed around chronology and international movements instead of national identiy. This story remains the canonical narrative of modern art to this day.

It seems, however, that even this story has exhausted its potential. It no longer feels vital or inspiring. Perhaps it’s time to reconsider to what degree a story based on chronology and the uniqueness of its characters (both artists and artworks)—a story we might call “Art History”—is still relevant, especially if it becomes apparent that art as a category can only be defined within this story. Instead of being perceived as the story, Art History should become a story. Similarly, the work of art should be treated as an artifact, as a product of a certain kind of Western culture rooted in the Enlightenment and shaped by Romanticism. From this perspective, the art museum would become an ethnographic museum.

—Walter Benjamin, New York City, 2011

×

Illustrations courtesy of the Salon de Fleurus, New York, and the Museum of American Art, Berlin. All image captions by e-flux journal