A few years ago, in November 2007 to be precise, I started a project on the history of the arts in the Arab world. I remember the month because I’d received a phone call that month from a woman by the same name.

November calls and asks me whether I am interested in joining a retirement plan just for artists, something she referred to as the Artist Pension Trust.

Until that point, I’d not even heard of retirement funds just for artists and I’d certainly not heard of the Artist Pension Trust. So I asked around and found out that The Artist Pension Trust—which I will refer to as “APT” from now on—was started in 2004 by two men. The first is a businessman, an entrepreneur whose name is Moti or Mordechai Shniberg. I soon found out that Moti had a partner, a man who came from the world of finance, and someone who turned out to be a risk management expert, even a guru of sorts: Dan Galai.

So how does APT work? How do Shniberg and Galai structure this retirement fund for artists?

They usually start by setting up shop in a city where they know that a lot of artists live and work—Berlin, for example. Once there, they contact a number of respected curators in that city. They then ask the curators to, in turn, contact up to 250 artists the curators know and respect. The curators subsequently call their artists and ask if they wish to join APT, just as November did with me.

If an artist says yes, APT signs a contract with the artist. This contract, to an extent, binds the artist to donate twenty artworks to APT over the next twenty years. On average, one artwork every year for twenty years.

When APT takes works in, it pays to store them. It insures them and preserves them. It may lend them out to exhibitions. But by signing the contract, the artist has also given the company the option, the right, to sell that artwork.

If and when APT decides to sell the artwork, 40 percent of the profits go back to the artist. If you work with a commercial gallery today, you usually get 50 or 60 percent of the sale price. A small, possibly significant 10 or 20 percent difference, but let’s not dwell on this for now.

Twenty-eight percent of the profits are taken by APT to pay for storage, insurance, and administrative costs. APT has expenses and this is how it recoups them.

And the remaining 32 percent of the profits—and this is what made APT very interesting to me, what made me think I should seriously consider joining—is always split, divided, shared, distributed among the 250 artists in each regional group.

This idea may seem simple but it is actually quite interesting. It is interesting because Shniberg and Galai seem to have figured out something very basic about the commercial art world, namely, that the commercial art world tends to be very fickle. This means that an artist is usually “hot” critically—but more importantly from APT’s perspective, commercially—for a very short period. And “cold” for years thereafter.

I read somewhere that the lifespan of a contemporary artist in the art market today is around forty months. This means that for forty months you sell well, and then for months, years, or even decades thereafter, you are lucky to sell anything at all.

Today, an artist who sells an artwork for five or ten thousand dollars is usually not surprised if six or nine months later they are unable to sell the same work for five hundred dollars. Artists who expect to make a living from the sale of their work in the market know this risk. We know it all too well. And it is precisely this risk that Shniberg and Galai are trying to manage. They do this by grouping artists into pools of 250 potentially interesting artists (what they refer to as the regional trusts). They figure that statistically speaking, it is probable that two or three artists are going to be “hot” and selling well at any given time. And because 32 percent of the profits are always split, divided, shared among the 250 artists in the pool, this risk is minimized for everyone, and every artist benefits.

This, it turns out, is a classic technique used in the world of risk management, which is Dan Galai’s expertise. Shniberg and Galai are simply applying this technique to the art market. That’s all.

Today, APT has set up eight regional trusts: New York, Los Angeles, London, Berlin, Mumbai, Beijing, Mexico City, and the trust I was asked to join, Dubai.

In a way, I was surprised that APT had started a Dubai trust. I did not know that in the Arab world in 2007, we already had 250 interesting artists—or rather 250 artists who were selling enough work that APT could build this kind of economy around them.

Today APT has signed contracts with around 1,400 artists, and these artists have already given the company around five thousand artworks. But if and when all the trusts close—meaning if and when 250 artists join each trust—then APT will have two thousand artists under contract who will give the company in the next twenty years forty thousand works, making APT one of the largest privately held art collections anywhere in the world—all this without the company spending a single dollar buying a single work of art.

I have to admit that this is not bad.

***

Alongside the retirement trusts, Shniberg and Galai also set up a parallel structure referred to as “APT: Intelligence.” But this unit is not for artists. It’s for curators. And here again, the idea is simple but fascinating.

Shniberg and Galai also seem to have figured out that today there are large institutional investors such as banks, universities, pension funds, and insurance companies that are interested in buying artworks as an investment. However, many are reluctant to do so because they know little about how the art market functions.

Let’s imagine that you are a state pension fund manager in Marseille and you are interested in investing in contemporary art from the Middle East to diversify your portfolio and because you keep hearing that this market is consistently outperforming the S&P 500. But you know nothing about contemporary art from the Middle East. Wouldn’t it be valuable if you had somewhere to go where you could talk to someone who knows a lot about this kind of art—someone who could advise you on which artworks to buy, when to buy them, and how much to pay for them?

To set this up, Shniberg and Galai contacted over one hundred curators. These were respected, renowned curators with expertise in different genres of art from different parts of the world. If you are interested in art from Mexico, you contact APT Intelligence and ask them if they have a curator who knows a lot about contemporary art from Mexico. They say yes. They put you in touch with the curator. You meet with the curator. The first ten minutes are always free, to see if you get along with the curator, if you like his or her sensibility. After this, for every thirty minutes you sit with the curator, APT Intelligence charges $300.

It turns out that many curators love this arrangement. This is understandable. Curators are always telling people about interesting artists or artworks, and they usually give out this information for free. With APT Intelligence, curators finally get paid for it. They are compensated for their previously undervalued information and labor.

Institutional investors like the structure too, because institutional investors do not necessarily trust commercial galleries. They think these galleries tend to promote their own artists. With APT Intelligence, investors can talk to someone who is to some extent independent from the product traded.

In addition, with one hundred curators, over one thousand artists and five thousand artworks, APT also actively promotes its collections by funding its own under-contract curators to produce exhibitions with its own under-contract artists, and under-contract artworks. As such, APT only manages to increase the value of the curators, artists, and artworks under contract.

Again, this is not bad.

***

It’s now mid-2008. I have yet to meet November. So far, we’ve only communicated over the phone and by email.

For some reason, I become quite interested in the man named Moti Shniberg. I decide that I need to do some research to find out how Moti made his money. After a few web searches over the course of a few weeks, I find out that Moti made a small fortune in the 1990s with an Israeli-based company called Image ID.

Image ID, it turns out, is a technology company that developed a system they called Visidot. Visidot scans tags and barcodes but instead of doing this with lasers, it does this with cameras, optically. But this is not what I found interesting about Image ID.

As I look more into Image ID, I find out that the company has a number of people on its staff and board who served in the Israeli army. This is not a surprise. We all know quite well that in Israel most men and women have to serve in the army. A few refuse, with grave consequences, but most end up serving.

But it turns out that many of Image ID’s employees and investors—and I discovered this after many more months and queries—not only served in the army, but served in Israel’s various elite military intelligence units: Unit 8200, Mamram, and Lotem.

The links between APT, Image ID, and Israel are already a problem for me for various ideological, political, and other reasons. One of the problems is simply the fact that Israel and Lebanon are still in a state of war. In Lebanon, any link between an Israeli person and a Lebanese person, or between an Israeli institution and a Lebanese institution, will spell trouble. And it does not matter if the Israelis you associate with are progressive, liberal folks. They may, for example, support the Palestinian cause more passionately than most Arabs. In Lebanon, it does not matter. Any link will spell trouble. I think to myself: Do I want to join a retirement pension plan started by an Israeli who made a fortune with an Israeli-based tech company where employees and investors have links to Israel’s elite intelligence units? Regardless of any other consideration, if word about this got out on the streets of Beirut, it might actually be dangerous, and not just for me. This may be dangerous for any Arab artist who joins APT. And I just wanted APT to be transparent about this. I just want APT to tell its artists whether this is true so we know what we’re getting involved in. That’s all.

A few weeks later, I take all this research to my first face-to-face meeting with November. I also prepare three sets of questions I want her to answer.

First, I want to know: Who is funding APT? Who are its investors?

Second, I want to know: Why is APT starting a Middle Eastern Trust, the Dubai Trust? Who are the 250 interesting Arab artists?

And finally I want to know about the links between APT, Image ID, and Israeli intelligence, because at some point I began to think I’d over-Googled Moti Shniberg and that the links were all in my head.

When I ask November these questions, she looks puzzled and embarrassed. Her face reddens and she says that she has no clue of what I’m talking about. She seems genuinely surprised and concerned by my questions and what they imply. She offers to put me in touch with her boss, a woman named Pamela.

A few weeks later, I meet Pamela and ask her the same three questions: The money? Dubai? Military intelligence?

Pamela also has no clue, but she does not seem surprised by my questions. I assume that November told her to be prepared for them. To her credit, Pamela is not only prepared, she also tells me that the only person who can answer my questions is Moti Shniberg. Am I interested in meeting Moti, she asks.

Am I interested in meeting Moti? Of course I am interested in meeting Moti. This is the man I have been wanting to meet since November contacted me eighteen months earlier. Pamela sets up an appointment with Moti. A few weeks later I find myself going to the APT headquarters in Manhattan, somewhere in Midtown.

I enter a big loft space. The receptionist welcomes me and asks me to wait for a few minutes. Before I sit down, I notice that in the background, there are thirty or forty young men and women sitting behind laptops, earphones on, typing frenetically. A typical scene in today’s tech world, so I don’t pay much attention to it.

Within a minute or so, Moti comes out of his office to greet me.

I should remind you that I was expecting to meet Mr. Israeli Military Intelligence. But the man who greets me is simply the most beautiful man I have ever seen in my life. I begin to wonder why I ever thought that a former military intelligence officer would not be beautiful to begin with. Moti is also impeccably dressed and clearly comfortable in his skin. He shakes my hand warmly, grabs me by the shoulder, takes me into his office, and begins to tell me how and why he started APT. (This is clearly a well-rehearsed and oft-told story. Before meeting Moti, I read the same story in one of his published interviews.) And this is how the story goes:

Moti is in a cab in Manhattan riding with an artist friend of his. He asks her whether she has any retirement plan. His artist friend says, “Moti, I am an artist. Artists have no money. Do you think we have retirement plans?” He then asks her, “Why can’t you invest your artworks like others invest their cash?” She looks at him and says, “There is no such thing. I wish there was such a thing.”

A few days later Shniberg is on the phone with his former finance professor Dan Galai. They come up with APT. Today, they’ve already filed five patent applications on APT’s investment model.

Anytime I meet an Israeli, especially one who is around my age, we inevitably talk about whether he or she “visited” Lebanon in the 1980s. We inevitably talk about Palestine, a one-state versus a two-state solution, and so on. Moti and I politely chitchat about all of this, and then I get to my questions.

“Where does the money for APT come from?”

As soon as I ask my first question, it becomes clear that Moti is not only beautiful but also very smart and very smooth. He replies, “Walid, I am sure you know that investors are people who prefer to remain anonymous.” Then a hint of a smile forms at the edge of his mouth: “But I will tell you and only you that we have investors from the United Arab Emirates.”

You understand what he is telling me. He is essentially saying: “If you are freaking out because you think that most of the money is Israeli, then relax. Even Arab businessmen are willing to invest with me, so why should you, as an Arab, be concerned about working with APT?”

And of course, now I want to know who the Emirati investors are. But Moti is so smooth, and I am so eager to get to my next question, that I don’t even ask about the Emirati investors.

Instead, I ask about the links between APT, Image ID, and military intelligence.

Keep in mind that I had been researching Moti and Image ID for over eighteen months. I had tracked every employee of Image ID. I knew what other companies they started, who they had worked for, and what army units they had served in. I had proof right there with me in my backpack in case Moti chose to deny his. I was ready. What could he possibly say?

As soon as I ask the question, something shifts. I cannot tell if Moti is bored or upset. I cannot read him anymore. He stays quiet for a few seconds and then says:

You are from Lebanon, right? So, I am sure you know how things are in Lebanon. I am sure you know how things are in Syria, in Egypt, in Saudi Arabia. And I am sure you know how things are in Israel. In Israel, many things are linked to the army. In Israel, the tech sector is often linked to military intelligence. Please don’t tell me that this actually surprises you? Please don’t tell me that you are one of those naive left-wing, head-in-the-sand pontificators who actually think that the cultural, technological, financial, and military sectors are not, and have not always been, intimately linked? Please tell me this is not who you are and what you think.

And of course, I am one of those—I would not say naive pontificators—but I also don’t want Moti to know this because all of sudden it all seems so embarrassing, so callow. And I am also not ready to leave his office. I’ve waited two years for this meeting. I cannot just leave now. I have to find a way to stay in the office. So I say to him, “Of course, Moti. Of course you are absolutely right.” And then I gaze into the office and I find myself asking, “Now these people out here, the thirty kids with headphones, what are they doing?” I had not prepared this question. I just asked it because I could not think of any other way to remain in the same room with Moti.

As soon as I ask this question, Moti sits up. His demeanor changes. He smiles broadly and says, “I can understand why you find APT interesting, but let me tell you what I find interesting.” Then Moti tells me about yet another company (and I am sorry that I have to throw the name of yet another corporation at you): MutualArt Services, Inc.

MutualArt, it turns out, is the parent company of APT. It owns all the regional APTs. It also owns APT Intelligence. Later when I try to find more information about MutualArt, I can’t. The company is a BVI company—it is registered in the British Virgin Islands, which means that its investors and structure can remain secret.

Moti then tells me, “MutualArt’s biggest investments today are not the retirement funds. It is not APT Intelligence. It is actually a website: MutualArt.com. Do you know this site? Do you use it?” “I use it all the time,” I say. It is actually quite good. MutualArt.com is a website for anyone who loves the arts and wants to keep track of art matters in general. For example, if you like the work of Francis Bacon, you can sign into MutualArt.com and register this preference. You like Sophie Calle, Francis Alys, David Diao, or my work, you do the same, and the site’s algorithm is fantastic. It scans the net and delivers articles, essays, exhibitions, and catalogs that matter to you and only to you. Essentially, MutualArt.com is a database of its users’ preferences.

Then Moti tells me, “MutualArt has millions of users who have registered millions of preferences, and as such we are on our way to building the largest data set about the art world anywhere. Except that our data set remains a noisy picture, and in order to turn it into a clear picture, with reliable tendencies, clusters, and nodes, we hired Ronen Feldman.”

Of course they would hire Ronen Feldman. After all, Feldman is the computer scientist, the man renowned for having coined the term “text analytics” in 1995. And I later found out that Feldman is also a graduate of the most celebrated Israeli military intelligence unit: Talpiot. It’s the equivalent of taking Harvard and adding to it Berkeley, MIT, Caltech, Princeton, and Yale.

Anyway. Feldman’s job is to write algorithms for very large data sets. He works with what is called “Big Data.” Take any large dataset, filter it through a Feldman algorithm, and within seconds—as if by magic—all kinds of tendencies, clusters, and nodes begin to appear. These tendencies, clusters, and nodes help to formulate questions and answers. The questions and answers MutualArt was interested in are primarily about the art world. Lets take auctions for example: When is the best time to buy or sell a painting by Andy Warhol? Spring, summer, fall, or winter? If in spring, is it better to sell in March, April, or May? If in April, is it better to sell in the first half of the month or the second half? On a Monday or a Tuesday? At Sotheby’s in London or Christie’s in New York?

MutualArt has answered these questions, and the result is an instrument, a financial product that MutualArt will soon be selling to institutional investors.

Then Moti also tells me about other questions that MutualArt wants to answer, such as: How many articles written by what writers, in what art magazines, using what art language will affect the performance of an artwork coming up at the next Christie’s auction?

The last algorithm Moti tells me about, the one they are working on as Moti and I speak in 2009, is an algorithm about color.

That’s right, color. More specifically, color in postwar European art. What percentage of blue? What percentage of red? What percentage of yellow? What percentage of black must a Picasso painting from 1946 contain in order to increase in value by 37 percent over the next sixty months?

As he’s telling me this, I begin to see how the risk management techniques of Dan Galai are being combined with the text mining expertise of Ronen Feldman in order to put in place—not in five years, but today—complex, dynamic, and real-time prognostic models about anything having to do with the art world.

The more Moti talks to me about MutualArt, mathematical algorithms, risk management, semantic web, text analytics, and Image ID, the more I get lost in all the details. For some reason, I also start to feel nauseated and tired, and I decide that I need fresh air. I don’t feel good all of a sudden. I decide that I need to end the meeting. I politely wind down our conversation and thank Moti for his generosity and his willingness to meet with me. I tell him that I need to go home and think about joining APT Dubai. (To this day, I have not joined). I stand up, shake his hand, walk out of his office, go down the stairs, and I find myself on Fifth Avenue before I realize that I forgot to ask him about the September 11 thing.

I forgot to ask him about why he tried to trademark the phrase “September 11, 2001.” I found out about this a few days before the meeting with Moti. At first I thought it was a joke, so I did some research and found the court records. This is what they say: “USPTO (United States Patents and Trademark Office) records indicate that the application was transmitted electronically at 17:37 on September 11, 2001.” At 5:37 p.m. on the afternoon of September 11, 2001.

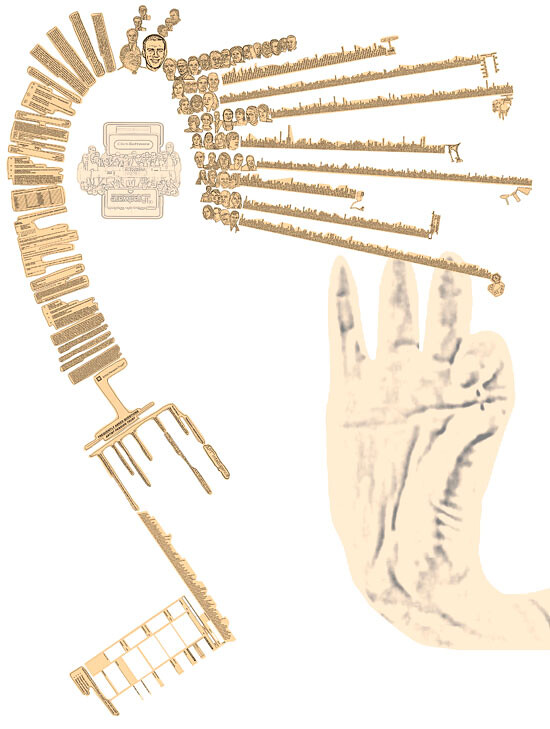

Detail of sketch for Walid Raad’s project “Scratching on Things I Could Disavow,” 2007-ongoing.

The towers went down at 9:59 and 10:38. Six hours later, Moti was already filing an application to trademark the phrase “September 11, 2001.” Six hours after the towers went down I was still trying to get my emotions in check, but this man had the amazing presence of mind, the masterful foresight to file a trademark application for “September 11, 2001.” How do you train for this?

But I don’t ask him about this because I am already a few blocks away, and I don’t want to go back to his office. I am tired, and at the same time I realize that I am actually quite relaxed and relieved. When I secured the appointment with Moti, I thought that I was going to find all kinds of insidious links among collectors, artists, bankers, the military, Israeli intelligence, and financial wizards. I thought all these links would somehow be too much for me. They would upset and agitate me. But in fact, when I look at this today, when I look at all of this, what can I say? “Yes,” I say to myself. “This is intelligent.” I would even say “this is very very intelligent.” But at the end of the day, it is also all too familiar. It is banal. It is expected. And I, for one, don’t find any of it insidious. I don’t even find it interesting. Certainly not interesting enough to deserve an artwork. After all, do we really need another artwork to show us (as if we don’t already know) that the cultural, financial, and military spheres are intimately linked? No. No we don’t. This may be intelligent but it is not insidious, and it is certainly undeserving of more of my words.

This text is (here and there) a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental. The text transcribes the walkthrough/presentation component of Walid Raad’s exhibition Scratching on Things I Could Disavow, recently presented at dOCUMENTA (13) in Kassel.