Through feminism I freed myself from the inferiority-culpability of being clitoridian … and I accused men of everything. Then I started to doubt myself and to defend myself through every possible thought and inquiry into the past. Then I doubted myself completely in rivers of tears … After that I was no longer innocent or guilty.

—Carla Lonzi, Taci, anzi parla1

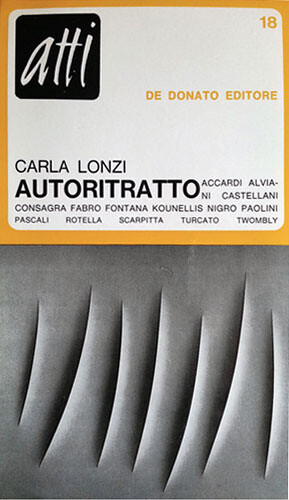

Carla Lonzi was a feminist, an art critic, a woman seeking freedom, and above all a politically creative subjectivity. When confronted by her legacy, we find ourselves in an uncomfortable position, where we run the risk of repatriating it and taming it or being dangerously affected by it. The problem with her oeuvre, which is also a problem with her persona—the two cannot be dissociated—is that it fights a merciless battle against complicity with the existing culture, against the incomprehension that accompanies each social and professional recognition, beginning with Lonzi’s own.

Her thinking can therefore be regarded as a weapon that spares nothing—including its own author—and whose unsettling power still remains intact and contagious today. But above all, her work is a precious tool because thinking against ourselves has become a vital necessity, as the illusion of a space outside power has completely faded.2 Lonzi speaks from the different point of view of the unexpected subject, which is the position of feminist political struggles from the French Revolution to the twentieth century.3 This stance abandons completely the illusion of equality with men and stresses the fact that we must know that we ourselves are the result of a shameful but inevitable negotiation with patriarchy, with the Law, and with other forces that structure our lives. There is no longer any “good side of the barricade,” because in this perspective, there are no barricades. Our subjectivities themselves are the battlefield. Hence, the importance of embracing the double bind into which Lonzi’s work throws us.

Taci, anzi parla, Lonzi’s “diary of a feminist” that she kept between 1972 and 1977, is an inextricable tangle of vanity and modesty, a pendulum swinging constantly between a completely self-centered approach and a passion for others that can lead to the deepest transformation of subjectivity. Many characters, although they bear fictitious names, are recognizable: Pietro Consagra, her companion of many years; Carla Accardi, with whom she founded Rivolta Femminile4; her sister Marta, who was also part of the group.

Subjectivity sieved by the practice of feminist consciousness-raising (autocoscienza) is the true protagonist of the book. The journal is a document of experimentation within relationships and a recollection of the profound changes that arise from it. Its subject matter is intangible, since it tries to retrace an amorphous and protean form of life, one stripped of its professional and social veils, reduced to its pure potentiality for revolt and freedom. The human material that appears through this process of subtraction is frightening and dangerous, something that capitalism, the social order, and patriarchal politics try to hide and erase. We somehow know, however, that the only way to do something truly meaningful is to plunge into this risky process. This radical approach to autobiography is a form of “existential nudism,” a desire for truth at the limit of obscenity. In a text from 1977, Antonella Nappi, who belonged to a different current of Italian feminism, wrote some enlightening lines about the political and existential content of nudity. She stated that in the experience of undressing together with other women, a woman discovers a wholeness of body and personality, accompanied by a quick and irreversible destruction of stereotypes. There is an undeniable closeness between consciousness-raising and this form of nudism that reveals feminists to each other. As Nappi writes:

To me, being seen and known was a joy, my body was a fact that I couldn’t disguise, I couldn’t hide parts of it, I couldn’t ignore it … I drew a lot of strength from the awareness not only that this body of mine was accepted, but that the process of getting to know me was both physical and intellectual, and that as a whole I was treated with love and sympathy.5

Through the gesture of classifying women according to their libidinal metabolism, Lonzi brings forward the brutality of feminine sexual organs and their hidden connection to our political position. Talking about the orgasm means talking about the compromises that we are all ready to make in order to reach and preserve pleasure. That’s why it is vital for her to state that her journal of a feminist is also a journal of a clitoridian woman.

In Taci, anzi parla, Lonzi’s rigor manages to hold together a heterogeneous, seemingly capricious mix of poetry, faithfully transcribed dreams, reflections, and anecdotes. This heterodox way of constructing a book is in itself a tactic to transcend literary genres and to mock certain pernicious conventions of culture. There is a fascinating demand made on herself and others that appears explicitly from the very first lines of her journal.6 She liquidates professional positions, even political ones, because they are toxically compromising: anything that accumulates and shines, like an electric device, must be dismissed. In a telephone conversation with her sister Marta on January 30, 1973, Lonzi, invited to meet Juliet Mitchell, simply replies that because Mitchell is an academic, she is not interested. After this episode, Lonzi describes Marta’s reverence for culture as an attempt by her sister to reduce her inferiority through an ingenuous sacrifice for a small and suffocating elite.7 “I so much wish she would come down from the stratosphere,” Lonzi writes. A merciless poem on Marta’s daily activities follows (whose final line gives the book its title8). In the poem, the paratactic series of duties that characterize the life of a cultivated bourgeois woman—from feeding her children to translating Plato, from buying clothes to fulfilling social obligations—is chaotically enumerated, to show how meaningless such an effort can be. The attempt to perform in all of these fields can only lead to schizophrenia and solitude: the dream of being a militant, an intellectual, an accomplished person, a mother, and a spouse appears as pathetic and dangerous. This open secret needs to be told over and over again, because without a radical change of perspective, women won’t truly have any other model for subjectivizing themselves—no matter how rebellious and anti-conformist they are, no matter what their sexual preferences are. In the preface to her journal, Lonzi gives her final word on the feminine skill of multitasking: “For me, doing one thing has a value because it prevents me from doing two.”9

A day earlier, she laconically remarked that Sylvia Plath “wouldn’t have died if, rather than acting like a writer, she had simply written about herself to free herself.”10 Lonzi’s own writings don’t exist to prove something or to inscribe themselves in a pantheon, a genealogy, a constellation. They come from the exploration of the abyss of solitude and pain, and they seek out the frightening emptiness of freedom. They are sledge hammers for destroying the palace of culture that men build higher and higher every day and for showing it for what it truly is: a fortress made only to exclude.

What is interesting in her conceptual and political operation is the total absence of a need to fight patriarchy with its own weapons: men must just be “abandoned to themselves,” which in no way means that they should be avoided or treated like enemies. Abandoning men to themselves comes down to refusing to play into the mythology of a complementarity constructed entirely at the expense of women. It means rejecting a sexuality that is nothing but a form of colonization. She writes:

The fact that women are objectified by patriarchal culture appears clearly in the difference between the destiny of adult men and adult women. Men create an attraction through their personality that gives an erotic halo even to their decay. Women realize brutally that the fading of their physical freshness awakens, in the best case, a form of tolerance that avoids or delays erotic exclusion. Men use myth, women don’t have sufficient personal resources to create it. Women who have tried to do so by themselves have endured such stress that their lives have been shortened by it.11

Lonzi’s personal life isn’t immune to this contradiction. This is probably where the inestimable value of her journal lies, when it shows how difficult and destructive her choices can be on a daily basis. The last pages and years of Shut up, rather speak are less and less populated by the collective of women, and are more and more centered on her relationship with her partner, Pietro, more concerned with the challenge of overcoming jealousy and finding a livable balance. We see her unspectacular, obscure, quotidian revolt, her absolute refusal to indulge her own weaknesses. Sometimes we can become exasperated: her lack of sympathy for herself can make empathy almost impossible for the reader. But this fearless exploration of contradictions, even when it leads to a dead end, is even more heroic if considered in relation to the peaks of strength that she reaches during the early years of Rivolta Femminile. It is fascinating to see how easily she abandons the positions of power she has attained through her writing. For example, on August 14, 1972, she writes:

At first I was accused of dialectical ability by the people who wanted to knock up thoughts at a lower level: I have used it to dismantle the danger of subculture and approximation. I have defended my intuitions with a line of reasoning that didn’t add anything to the thoughts of these women but that protected them from the common confutations of the masculine world. This allowed the feminists to abandon the suspicion that the absence of men from the meetings meant that men, with their argumentations, would have made us clam up.12

By putting her intellectual power at the service of the feminist cause and by deciding to simply give it up in order to concentrate on herself, Lonzi refused to capitalize on her positions of power within and outside the collective. She said she wanted to finally get rid of the residue that the passage through the masculine world had left on her. She wanted to give up theoretical writing. The ease with which she abandoned her intellectual privilege is puzzling when we measure the importance of her writing, but somehow it is totally coherent: she could only find power in her lack of attachment to writing as a cultural practice. In fact, her skepticism towards culture is the very source of her theoretical strength.

In “La donna clitoridea e la donna vaginale” (The clitoridian woman and the vaginal woman), Lonzi demolishes psychoanalytic fallacies regarding women’s pleasure. She reveals how an autonomous feminine sexuality, one that dissociates the sex act from reproduction—even within heterosexual relationships—can be the starting point for a different type of subjectivization for women. For Lonzi, being a clitoridian woman has not only sexual connotations, but existential and political ones as well. Whenever “a woman claims a sexuality of her own where the orgasmic resolution isn’t connected to any mental condition that accepts slavery,” then

she begins thinking in the first person and she doesn’t listen to any enticement … She doesn’t want to hear emphatic points of view about sex, unity, pleasure. Finally, in full possession of her sexuality, no one can convince her that her efforts will be rewarded and that the pleasure of a moment will be worth a life of slavery.13

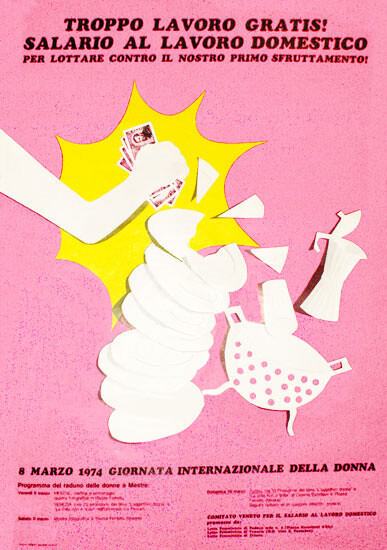

In the Italian feminist ultra-left of Lonzi’s time, a deep connection between knowledge of oneself—especially of one’s own pleasure—and satisfaction was regarded as the only way to reach autonomy. There was a vivid awareness that colonization operates through the mind and the body, and the only way to reach freedom was working on one’s own subjectivity.

What is probably unique in Carla Lonzi’s work is the search for a balance that can maintain this independence, joy, and pleasure for women—a search for the formula for the reproduction of what one could call the “revolt force.”

If her oeuvre is representative of the Italian Seventies—although it truly has its own incommensurable specificity—it is because it completely identifies politics with the existential space, with the practices of subjectivization and desubjectivization. This element constituted the strength and the weakness of the struggles of that time and, inevitably, the complication of handling what is left of them.

From this perspective, a politically precious document is Lonzi’s Vai pure (Now you can go), a dialogue with her partner, Pietro Consagra.14]).] Here, her separation from Consagra is clinically documented through a transcription of their recorded conversations. The dialogue also represents Lonzi’s ultimate separation from the art world and its ethics. Lonzi in fact abandoned her profession of art critic when she quit her illusions about the freedom of artists, when she understood that the possibilities offered by the creative space don’t come without the compromises and mythologies that the artistic profession is based upon.15

In Vai pure, the couple becomes a sort of metaphor, a theater where the forces of society play out. Work and the labor of love are the two poles around which the discussion revolves: Lonzi and Consagra are separating because Lonzi doesn’t let him work the way he would like. Lonzi says:

If one gives priority to the production of the artwork, to the detriment of the human relationship, the human relationship inevitably cannot fulfill itself, because the two things are competing against each other … The human relationship is instrumental. That is generally true. When conflicts take place, like between you and me, there are no chances because you give more value to the artwork, and the whole of society is behind you in this. The fact that I get scandalized doesn’t bother you at all because you are integrated within society, so you don’t see any damage to human relationships because it is totally accepted and nothing counts but the artwork … From the moment I become a negative element that you resent, you say, “It’s better for me to be by myself or to look for other types of contacts,” because they are contacts, and not relationships … Then you say, “All right, I will live without human relationships,” but in that dreamy atmosphere that you have always carried with you, which is the mark of your culture, whatever that is, you think that doing this will help to develop your artwork.16

Lonzi delivers her objections from the standpoint of the human relationship as a means without an end. She dangerously unmasks the demon of work and the gender struggle hidden inside love.

In her diagnosis of the situation, it is tempting to compare her position to the position of the artist confronted by the professional apparatus: women, she explains, haven’t rebelled against the myth of society because even in their private lives they are still crushed, unrealized, oppressed. They cannot even reach the doorstep of life with sufficient stability, because they start with a handicap. They look for love and a relationship with a male partner, but this relationship will only take place in a way that reinforces the partner, helps him to face the world from a stronger position. A woman’s need for love was indeed created by patriarchy to help men succeed in life. Women give love an independent value, while men give it an instrumental one. “And then men,” she writes, “recuperate this love as an absolute value in the arts, in poetry, in the artworks that live and grow through these non-relationships. Therefore men, after preventing [women] from living love, offer to them its symbol as an object.”17

The sublimation involved in artmaking is politically unacceptable to Lonzi. She talks about a demand that art makes at the expense of human relationships, and Consagra cannot really contradict her because he claims that an artist needs the “complicity” of his partner to go forward, a complicity that is more than simple support. When Lonzi asks for another example, he says, “One cannot make love with someone who is whistling.”18

What is interesting in this dialogue is that Consagra, as a man, seems to embody the artwork and its professional values, while Lonzi embodies a desire for radicalism, a need to unmask the violence of productive dynamics, and the possibility of living a life without a frame, a life that questions itself and intensifies itself without hiding behind obligations, habits, opportunism—a life that is, in fact, truly an artwork. By the end of the book, farewells have become inevitable. Lonzi says:

I don’t know how to name it. We eat lunch with the feeling that you have to go to the studio, you come back in the evening with the feeling that you must recharge your batteries and in the morning you are off to the studio again … Even when we are at Elba Island [on holiday], you don’t want to go climbing on the rocks, because you want to work on a drawing, on a project, on something, and you accuse me of stealing time from your work. You give me the remainder of your time in the afternoon. We don’t walk around the island, we don’t take walks, we meet people only and exclusively for work, we have restricted the world for ourselves to the people that are interested in your work, whoever they are, clever people or idiots, but it is the work that counts. You must understand that our whole life is structured by work, all of it, that we are never together for ourselves. It’s just a pause, a rest from work. The vital, conscious, and active moment, the promised land is work … You don’t have a schedule, you don’t have a job, you don’t have obligations, but you create a more constraining situation than if you had a job and a boss.19

Consagra then responds, “Then you make a program for life, you make the program.” In this remark, all the tragedy unfolds: Lonzi needs to escape from the very logic of the program, she doesn’t want to internalize obligations and organize a plan. She tells Consagra how all this makes her feel desperate, and in the last lines of the book she asks, “Do you understand me?” Consagra answers, “For sure.” Then she says, “Now you can go.”20

Carla Lonzi, Taci, anzi parla: Diario di una femminista (Shut up. Or rather, speak: Diary of a feminist) (Milan: Scritti di Rivolta Femminile, 1978), 187.

Lonzi’s political vision is articulated very clearly in “Sputiamo su Hegel” (Let’s spit on Hegel) where she affirms, for example, that “the proletariat is revolutionary towards capitalism but reformist towards the patriarchal system,” that “women’s oppression doesn’t start in time but rather hides in the darkness of origins,” and that Communism was incapable of including feminism because it was an essentially masculine project. See “Sputiamo su Hegel,” in Sputiamo su Hegel: La donna clitoridea e la donna vaginale e altri scritti (Let’s spit on Hegel: “The clitoridian woman and the vaginal woman” and other writings) (Milan: Scritti di Rivolta Femminile, 1974), 29 and 19.

Maria-Luisa Boccia, “La costola di Eva: Il Manifesto” (Eve’s Rib: The Manifesto), November 22, 2011. See →.

Rivolta Femminile (Female Revolt) was a feminist group and publishing house founded in 1970 in Milan upon the publication of “Manifesto di Rivolta Femminile,” a text written by Carla Lonzi, Carla Accardi, and Elvira Banotti.

Antonella Nappi, “Nudity,” May 4 (June 2010, [1977]: 71–72.

“I needed to get out all my dissent about the image that I felt obliged to stick to in the eyes of others: unexpressed and happy to represent something, but not myself. This frustrated my efforts to communicate. In fact it frustrated me, it prevented me from existing. Now I exist: this certitude justifies me and confers upon me that freedom in which I alone have believed and that I have managed to obtain.”Taci, 9.

Taci, 247.

“Sister, where are you my sister? / Are you playing the piano / or translating Plato? Are you feeding / your baby girls or going shopping / totally absent? Don’t you like / the skirt that you have bought? Are you unsure about the color? / The concert is starting, it’s time / for the meeting, the train is leaving, / a friend is coming from London, / a friend of Sandro’s. Were you expecting me? / Oh you are busy. / I find you pale but I see that / you are eating. The older one interrupts / all the time, and so do the little ones. / Do you really answer to everything? / Don’t you neglect anything about them? / Do you want them to be happy with their most extraordinary / mommy all to themselves? / And as a sister, a friend, and everything else? / Why are you putting the phone down? Haven’t you suffered enough from solitude? / And what about me? Do you know me? Do you care? Do you count on me? / It doesn’t matter … Shut up. Or rather, talk.” Taci, 247–248.

Taci, 9.

Taci, 246.

“La donna clitoridea e la donna vaginale” (The clitoridian woman and the vaginal woman), in Sputiamo su Hegel, 116.

Taci, 41.

“La donna clitoridea,” 107.

Lonzi, Vai pure: Dialogo con Pietro Consagra (Now you can go: Dialogue with Pietro Consagra) (Milan: et al., 2011 [1980

Lonzi writes in her journal on August 16, 1972: “When the possibility of a women’s movement appeared, I felt that I had everything ready to offer: the knowledge of men and a life of research that was the implicit content of my life. With this opportunity, I have realized that an identification of myself was happening automatically, which had been left in suspense until that moment, and in that impossibility I had consumed an incredible amount of energy. So I got to feminism, and that has been my party. Someone had to start it, and the sensation I had was that either that would be me, or else nobody would have saved me, so I did it. I had to find who I was, in the end, after accepting being something I didn’t know. This isn’t a creative process because what bothers me with the artist is that the role of protagonist requires a spectator.” Taci, 44.

Vai pure, 35.

Vai pure, 29.

Vai pure, 132.

Vai pure, 131–133 passim.

Vai pure, 133.