The Hymnal

Some out there are passing around a prophecy about Pope Francis that speaks of him as the last Pope of the Catholic Church. After him the sky will shudder and God will bring the flood. This seems to be supported by the Church’s familiar numeric appendage to the Pope’s name: he is the first Francis but not Francis the First. Is it a sign or some papal scheming?

Pope Francis wants to replace the gold cross with one made of wood. He wants to give the church back to the poor. Popes have their own reasoning for such acts. One need not investigate the Pope’s motivation on these matters, but rather their long-term impact, if any.

Alternatively, let’s embark on another Sisyphean pursuit.

Since the sixteenth century, writing has aspired towards permanence. That horrific century brought a succession of powers, churches, popes, writers, politicians, and artists who made attempts at immortality by making their marks on the rocks of time. The Catholic Church has remained tenaciously faithful, in a sense, to the fifteenth century. The Church’s guards, popes, teachings, sermons, and its Bible have been the center of attention since Michelangelo finished his marvelous works at the Sistine Chapel. As is the case with other holy books, the Bible is a hymnal. Its hymns are recited and sung in the same fashion as the hymns found in other holy books. The fact that the Bible is a hymnal means that there’s a strong tendency, which has remained strong for centuries, to convert it from the written to the oral realm. In the latter realm, it is no longer simply a book, a physical artifact that will fall victim to the deleterious effects of light and humidity, but an invocation that unites all, regardless of their faith. The recitation and the sound of bells are meant to be familiar even to heretics and infidels. This phenomenon finds a perfect match in other holy books like the Torah and the Quran. Religions have, since the beginning, sought to make the word of God familiar and approachable. People who treated divine texts as primarily written words became priests, irrespective of their vocational inclination: infidels, heretics, atheists, priests, or theologians. Voltaire is no less priestly than St. Augustine.

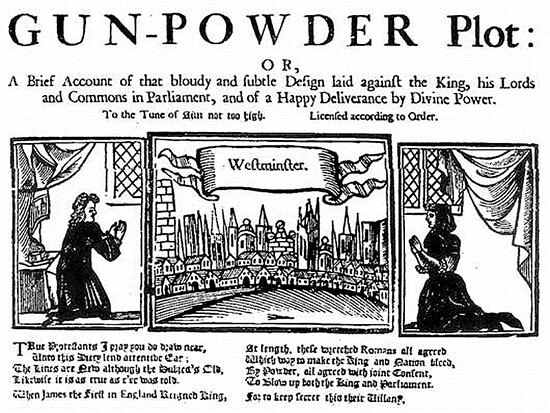

The sixteenth century was pivotal in the history of the Church and humanity at large; it gave us gunpowder, the printing press, and America. The printing press instituted the book as the replacement for the cathedral, as the book, with its ability to clone itself endlessly, could outlive the cathedral. Thousands of identical copies are spawned from one manuscript. That’s thousands of pocket-size cathedrals that people can take with them everywhere. Erwin Panofsky said that cathedrals are the rhetoric of the Church, but printed books are the rhetoric of the Enlightenment and its own cathedrals. With early books there was also an America—America the Protestant. This church was born into reality through the book and, like Calvinism and Lutheranism, stayed confined within the book. And despite the earnest efforts of Protestant televangelists, the church never morphed into signs, building facades, or TV screens.

Before the advent of the age of TV, the internet, and mobile phones, there was the balcony where the Pope addressed the world. It looked like a TV and had the same influence. Pope Francis’s address to the throngs of the faithful from that balcony transformed them into a unified, collective spectator, unlike cinema, where viewers are individuated in public space. The believers standing in Piazza San Pietro under a cloudy sky are patrons of a carnival; they share the same experience and are one in their fervor and desire to sacrifice themselves. The Catholic Church may have preceded television, but it functions in the same way.

The Papal loggia affords the assembly in the Piazza an overwhelming feeling of repentance, piety, and unity in one giant body that is a sum of its small parts. A person can sit in front of the TV fully prepared to receive the sermon and atone for his sins and be absolved at the same time that he is bestowed the power to judge other sinners. Individuals are all sinners but forgiveness is a community act. Watching a soap opera on television, a spectator might condemn a man for being unfaithful to his wife, or might sympathize and express solidarity with him. At the same time, this spectator himself could be guilty of the same act of infidelity, yet not judge himself as harshly.

The Last Days of Gunpowder

Hiroshima was built at the end of the sixteenth century, the century of America, gunpowder, and the printing press. And in Hiroshima, that century was buried on August 6, 1945. It’s still unclear why America, the reigning infant of the sixteenth century, decided to drop the A-bomb on the city, especially considering that the Japanese Empire was in decline and on the verge of surrendering. Yet America dropped her bomb on the city, decimating 90 percent of the buildings and infrastructure, killing 80,000 and injuring another 90,000 inhabitants of a population that totaled 350,000 at the time. The survivors were witnesses to the triumph of the history of gods and the end of human history. Among the Japanese people who experienced the kind of destruction one would expect at the end of days, were there any who loved America and hated the Emperor? Common sense would say: yes. Did America drop the bomb because General MacArthur decided to burn the Japanese people back to the Middle Ages? Such a historical intent is unknowable.

What is known is that the bombs dropped in the summer of 1945 ended the long era of gunpowder. Causalities of conventional war are too numerous to count, but what is known of such causalities is that they happen in circumstance similar to car accidents and drive-by shootings. These kinds of deaths occur simply because one happens to be in the wrong place at the wrong time. A soldier in the battlefield kills indiscriminately—gunfire and stabbings directed at whomever happens to be present. In contrast, the target of the bomb in Hiroshima is entirely ethnic, akin to the way Abu Musab Al-Zarqawi chose his victims. It is a crime against the human race, or a part of that race, because the bomb acts without regard for the political views of its victims. To be murdered because you are American, or Japanese, or Kurdish, or Christian, or Muslim is fundamentally different from being targeted because you are a soldier. In this way, it is possible to draw a distinction between wars among states, which are beholden to the will of their citizens, and wars among kingdoms, which hold the purity of lineage as the core of their power. Before the sixteenth century, every kingdom had its own religion. After that, states and cities were born, and with them came the citizen. A citizen might defend geography, but not history. A citizen might defend the borders and the sovereignty of the state to which he or she belongs, but not the purity of a race.

President Obama repeatedly warned President Asad of the consequences of using chemical weapons against his own people. Such an act is reminiscent of the Hiroshima bombing insofar as it targets a whole ethnic collectivity, not an individual. President Obama laid out some strong arguments for intervention, and added that the world would not forgive Asad for using some of the worst weapons known to man to exterminate the Syrian people. What is happening in Syria is no less than ethnic cleansing.

Today, the death toll in Syria is equivalent to that of Hiroshima. Some of the oldest inhabited cities in the world—certainly older than Hiroshima—are being brought down on their inhabitants’ heads. The extent of the civil war in Syria leaves no doubt that it is no longer a war involving states or borders or citizens or geography. It’s a war of histories, lineages, and ethnicities. This situation resembles a bitter and horrific reenactment of Judgment Day: life and death intermesh into an indefinable unit, human law is obsolete, death is not punitive but patriotic, and people are killed for their ethnicity instead of for their actions. The tools of death in Syria are, for the moment, the same conventional tools used since the dawn of war: daggers, swords, guns, and cannons. Yet the death scene itself overpowers those tools in the way it evokes divine punishment or nuclear holocaust.

America: The Cure and the Disease

The offspring of the sixteenth century is a land of immigrants. The early ones were the Europeans, who came with their African slaves. But later, people started immigrating to America from every spot on earth. Since its birth in the early European Renaissance, America’s fervor to establish the kingdom of man on earth has been relentless. Hannah Arendt described the American Revolution as the only one that was successful, until further notice. It was successful, according to Arendt, because it was a revolution propelled by abundance and not misery. The second American president, John Adams, was charged with giving meaning to that part of the Declaration of Independence that outlines the pursuit of happiness. Adams noticed that Americans interpreted happiness as ownership. This founding father saw happiness as the cultivation of an independent mind. Individuals would develop independent minds by assembling and engaging in public debates to form their own opinions. Although Adams’s brilliant idea didn’t change America’s habits, it laid the foundation for a country and its citizens. I don’t think today’s America is there yet. Opinion in the US is shaped by specialists, and American administrations exercise opinion-making in what functions like a large university: appointees serve until their contract expires, after which they go back to their hometowns to proceed with living the American dream through the accumulation of property. It is a country of happy retirees who own what they think will bring them happiness. Based on Adams’s observation that happiness is realized through social and intellectual activity, it is possible to draw up the blueprint of a modern democratic state and its cities. These cities might resemble Washington, D.C., since the pursuit of happiness requires citizens to participate in debates on public matters, which in turn requires a space for public assembly that is owned by the people, who are the source of authority.

For such a debate to take place in a royal court or a mosque or a church, it would have to be subordinated to the interests of the patron of that venue. By contrast, Washington, D.C., is a capital city realized in its entirety as a public space; the houses and apartments there are either leased, or purchased for a defined period of time depending on use. Each newly elected president brings with him new city occupants in the form of new staffers and advisors to replace the former president and his entourage, who go back to their home states. The same goes for military personnel and public servants. If you were to ask an American soldier where he was from, he would answer: “I’m from nowhere.” That’s because a soldier’s definition of home comes from where he happens to be stationed at any given time. But America remains, despite her uprooted soldiers, the undisputed land of immigrants. All Americans come from lands beyond the sea. This vast country hosts people of many ethnicities who, ironically, work hard to maintain their ethnic purity. There are, naturally, interracial newborns, but first-generation immigrants insist on staying faithful to their racial background. The Irish will remain Irish, and the same goes for Italians, Arabs, Chinese, and African Americans.

Public affairs in America are taken care of by employees, not religious authorities. That’s why politics and public affairs are the domain of the secular. In America, secularism is strictly concerned with power-sharing and managing public resources. This is the core of the America that Adams conceived of. Parallel to this lies the America that looks for happiness in ownership, and enjoyment through ostentatious living. This America looks forward to a comfortable retirement in an earthly paradise—a paradise that is based on material wealth but that nonetheless resembles the paradise of the religious realm.

This creative, schizophrenic America is secular when it comes to war and politics, and religious when it comes to property and social issues. Because of its secularist politics and its multiple ongoing wars, it seems today to be the only country in the world burdened by its tremendous power.

This America played God in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and today it is the only country that doesn’t want to play God anymore. It’s a tremendous, depleting, and terrifying burden for a culture to take on. Only gods are meant to carry that load. In America, faith is individualistic and private, and citizenship is public and collective.

Despite all of that, America is the creator of the tools that led to the disarming and decline of the sixteenth century. It gave the world the atomic bomb, the television, the internet, and the computer. It was also instrumental in spreading these inventions around the world. With television, oral and visual histories became popular again, and contemplative reading and writing fell into decline. However, many people claim that, with the widespread use of computers and the internet, writing has regained some of its luster.

Let’s go back briefly to Nietzsche to remind ourselves that collective human memory—what makes us human—is activated by pain and suffering. To oversimplify Nietzsche, we could say that our collective memory has privileged reactive thinking as a tool of evolution. A man who likes a woman for purely physical reasons is ready to reproduce with her but calls this attraction love. This reactive thinking extends to food, sleep, comfort, sport, work, and achievement. In fact, this sense of urgency to react is directly connected to scarcity. When we read Joseph’s story in the Torah, or the Quran, or The Sorrows of Young Werther by Goethe, we are taken by the pain and joy of very specific people. For these people to invest so much effort into finding their better halves elevates love to a universal human value.

With the supremacy of television and the ubiquity of the internet, this elevation of love becomes nearly impossible. No woman is a man’s better half and no death is pure and final on TV. Television recycles better halves infinitely, giving them new names, new bodies, and new faces. It also portrays death and suffering in myriad ways, creating a variety that impels us to admire and be entertained by it. This bombardment by images of horror leaves little room in one’s heart for a tinge of discomfort, like the one Lionel Messi might feel upon missing a shot on goal.

All of this was impossible to predict before the events of the Arab Spring. It has become clear, with the abundance of images of death and bloodshed coming out of Syria in the past two years, that death itself has become incapable of pushing us, even for a tiny moment, to think about the death of an individual. More deaths will follow, and staying up to date with them will mean having no time for sorrow, and certainly no time to mourn.

Razan Zaitouneh, the renowned Syrian activist, has written about her activities during the Syrian crisis. These activities have involved examining dozens of daily videos of Syrian deaths from across the country. She said that one time she had to review more the sixty videos multiple times to be able to document and verify the deaths of people taking their final breath. Being the delicate soul that she is, she decided to blog about them as an attempt to grieve and mourn for each and every one of them. The acts of grieving and mourning are the two things that empower a person to become a human being and an individuated citizen. Conversely, indiscriminate death begets nothing but the kind of anger that turns a person to blind faith and makes citizens behave like masses that don’t know whether they’re sad, angry, or desperate—or even dead.