Backstory

Ethnography’s reach into the pluriverse of the contemporary moment has no shortage of surprises. In the summer of 2011, my interest in the anthropology of outer spaces drew me to Prague, where I participated as an official “observer” in an international conference on “space security.” The purpose of the event was to bring together space policy professionals and experts from the United States, Europe, and Japan, in support of drafting an International Code of Conduct for the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space. The urgent problem of the day concerned the massive amounts of debris in outer space and its risk to human life, to scientific research and diplomacy, and perhaps most importantly, to telecommunications on earth.

Haunting the conference hall were two event icons: one a targeted destruction, and the other an accidental destruction, of spacecraft and satellites in low earth orbit. Representing the first category was “The Chinese”: the event of January 19, 2007, when the Chinese military shot down one of its own satellites in a region of space occupied by US spy satellites and space-based missile defense systems, and the US response of shooting down one of its own satellites, SA-193, supposedly heading towards earth filled with toxic fuel, almost exactly one year later. Together, these threatened to set off an international arms race, and they inspired worldwide protest.1

In the second category was “Iridium”: a spent Russian Cosmos 2551 satellite that had slipped out of orbit and, over Siberia on February 11, 2009, slammed into a communications satellite built by the US company Iridium.2

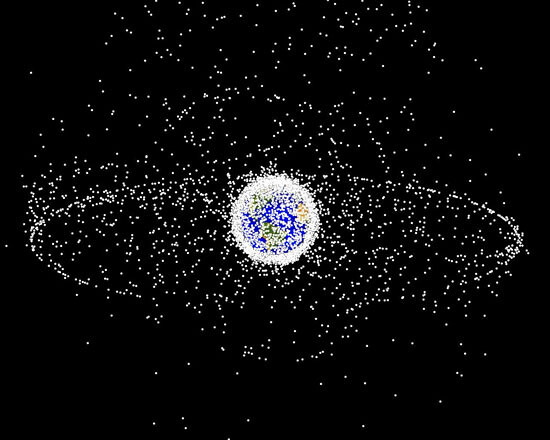

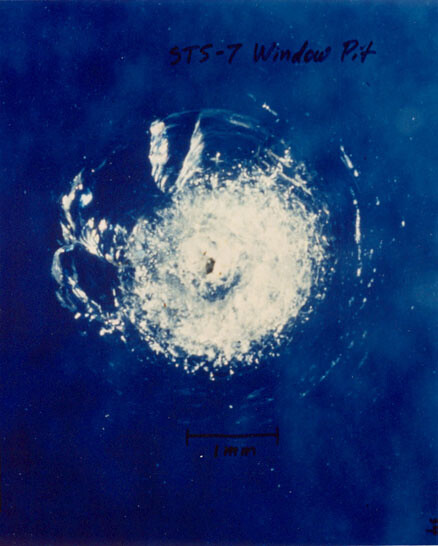

In the case of the Chinese missile that researchers are particularly eager to cite, the impact spalled off more than 150,000 pieces of debris larger than 1 cm.—so it was traceable, as well as capable of creating yet more debris. The American debris cloud matched this.

All in all, then, we are talking about some hundreds of thousands of traceable bits, not to mention self-forming globules of toxic fuel, along with radioactive material already orbiting from diverse sources which include machines disabled by natural objects such as meteorites, things discarded by inhabited spacecraft, and debris moved from the space graveyard orbital zone into lower altitudes by lunar perturbations, radiation pressure, atmospheric drag, and computer failure. And like booster rockets and other fragments from launches both successful and failed, it can all free-fall to earth as “space junk” of one form or another.

But “Iridium” and “The Chinese” were the words that buzzed around in coffee breaks in Prague, uttered by experts who didn’t have to mention them, but always seemed to need to—the latter finally being voiced as “the elephant in the room” by Admiral Dennis Blair, Former US Director of National Security and Commander-in-Chief of US Pacific Command, who, in a totally unexpected appeal to diplomacy, warned of the extensive dangers of military brinksmanship3—and also knew an unwinnable fight when he saw one. Since that time, the issues have continued to occupy space policy conferences and workshops, as well as government documents such as the European Space Policy Institute’s Report 44, titled “Space Crisis Management: Europe’s Response” (March 2013), which considers global crisis scenarios precipitated by debris blindsides.

***

What interests me in all this is the element of cosmic exo-surprise—the out-of-the-blue-ness not yet or maybe not even possibly becoming “Aha!”—a moment of collision of the producers of outer space as an installation zone for ever-accelerating terrestrial networking technologies, with the social orders that have produced them and that they support. In this regard, space debris is an ironic instantiation of the effects envisioned by Noys (as a politics) and Shaviro (as an aesthetic) in their embrace of accelerationism. Gean Moreno’s fine description of the issues bears quoting at length:

Embracing capitalism’s penchant for always undoing more and more in its quest for self-perpetuation and growth, for treating any blockage as an incentive to crank up its rhythms, accelerationism experiments with the possibility of speeding up and intensifying capitalist relations and ways of living, exacerbating its dissolutions and its velocities, until something breaks. Accelerationism aims to rev up crisis and render it unsustainable, to pipe even more energy into processes of social fracture, to exacerbate the fragmentation of experience, and to intensify sensorial overload and subjective dispersal in order to drive masochistically toward an incompatibility between capitalism and forms of excess it can’t accommodate.4

Interesting things happen when we translate this tactical orientation to the extreme environment of outer space. For one thing, the effect that accelerationism aims for is already a given there; the work of excessive velocity has been taken up by the disinterested force-fields and entities of “space as itself,” as I have elsewhere termed it,5 and the results are already threatening global communications and other infrastructures. The implication is that the purview of accelerationism is not extreme enough, as it has not given voice or any degree of agency to nonhuman actants. So the question becomes: Why not?

Here I want to consider how mainstream media aesthetics reclaim what Deleuze terms “control society” performativity through images of the depersonalized alien threat of space debris; how, as “parallel narratives” (Peter Sloterdijk’s terms) such images are capable of shattering under-control futures in intimate spaces that don’t see them coming. Distinct from government-generated Cold War narratives of fear control which, as Masco brilliantly argues, persist as present-day extreme disaster management and response scenarios,6 space junk imaging trades specifically on the velocity of exo-surprise and the uncontrollability of “space as itself”—displacing to the cosmos accountability for earthlings’ failings. Represented as coproductions of nature and technoculture that exceed terrestrial limits at the start—which is to say, they can appear initially as transcendent forces relative to social conflict on earth7—space junk materializes a claim for blindsiding as a natural rather than cultural condition of social times “hypermediated”8 and habituated to crisis. It is a situation that calls out for alternative modalities and counternarratives.

Where Space Junk is Concerned, Nobody Likes Surprises

Not long ago, as I was clicking through television stations in my study, I caught the tail-end of an ad on the SyFy Channel which stopped my channel surfing and made me laugh. It showed a space capsule crashing through the ceiling of a university classroom into a gigantic jack-in-the-box, startling some student insurance agents as their Farmers Insurance professor stood by, unphased. “Obscure space junk falling from the sky? We cover that.”

The jack-in-the-box ad spot, with its theme of out-of-nowhere materializations, had, as it turned out, appeared just a few days earlier on great-ads.blogspot.com, as I sat down to write the first draft of this paper. It included information that the capsule actually weighed as much as it appeared to in the ad, which the director, known for sitcoms, had insisted on for verisimilitude; it mentions the effect of the collision with actual tin, dust particles flying, and how the sound affected the actors. And even the chimp who ejects from the capsule off-screen and parachutes in at the end of the commercial was animatronic—no computer graphics imaging was used in the campaign. Materiality would be the key to illocutionary impact.

But wait—wasn’t there a famously successful ad for State Farm Insurance some time back, informing us that damage to property from “space junk” is covered by State Farm—a competitor of Farmer’s and the company they were most concerned to distinguish themselves from? This ad used a video game scheme, with a huge robot from outer space bent on random destruction of a suburban neighborhood. Meanwhile, blasé onlookers comment on what is happening to their neighbor, as if all this were only to be expected. I wasn’t surprised to find that the ad had sparked an online interactive version of itself. But I was surprised that the game allowed players to virtually destroy their own homes—and afterward call a State Farm agent in their area.

Of course, insurance companies know their algorithms, and their marketing strategists know their psychosocial science. So one can assume that editor-in-chief Holly Anderson’s piece on the State Farm Learning Center webpage, isn’t coming out of nowhere. She writes:

Americans were enthralled this month as to where debris from the Upper Atmosphere Research Satellite (UARS) might fall. Anyone wonder if the resulting damage to your home or vehicle is covered? NASA deployed the UARS, via the space shuttle Discovery, in 1991. After 20 years in orbit, it was expected to crash through Earth’s atmosphere Sept. 22. While most of the debris from the UARS satellite will burn up as it accelerates through the atmosphere, NASA predicted several dozen fragments of debris to impact the Earth … While claims are handled on a case-by-case basis, you might be surprised to learn damage from satellite debris, a.k.a. space junk, likely would be covered under most insurance policies.9

At the time this statement was published (September 2011), a NASA space debris expert, Nicholas L. Johnson, was giving one-in-a-trillion odds against UARS debris striking any one person on earth.10 And soothing voices on network news were reminding us that earth was, fortunately, mostly water (not so fortunate for sea life but, still …).11

All this is to say that when the jack-in-the-box commercial made an appearance in my study via the SyFy Channel and then again later during a Patriots-Cowboys game—this time closer to the predicted date of impact of space debris from yet another monster spacecraft, the thirteen-ton Russian scientific research probe Phobos-Grunt—I felt fairly certain that the “creatives” at RPA agency in Santa Monica and DDBChicago (respectively) had gambled that my world wasn’t feeling all that predictable, much less safe or secure, and on another level, that my anxiety wouldn’t be discriminating between terrestrial and extraterrestrial objects, or between actual and possible ones.

Of course, we could deconstruct to death these so-called “content marketing” ad spots, and someone should. But the relevant point here is how this educative model engages its practitioners. One content marketing conference-goer tweets: “Find/create the relevant truth, deliver it in a fresh way, and people will care.” Another: “Our job is to create relevance, not awareness.” Particularly as applied to accident insurance, which trades on hyper-vigilance, the capacity of content marketing to cut loose the awareness function of mainstream media suggests that this already has a naturalized place in the cultural order of things, or else is free to find one somewhere categorically other than compensatory security for purchase. The closest relative at hand is reportage—the technology of choice for delivering social facts for which relevance can be taken as culturally given, and social awareness as the primary work at hand.

William Mazzarella cuts to the point of the commercial-news relationship in recognizing affect as the armature of effective social projects, “if by efficacy we mean its capacity to harness our attention, our engagement, and our desire” in our “interpellated” lives as “consumer-citizens.”12 And indeed, the hyphenation works here as an invitation to dwell on the affinity of reportage and commercial advertising in terms of the aspirational gap between them. Reportage, which might be taken as appealing to “the legal assemblage of citizenship and civil society,” “seeks affective resonance” for moving us to awareness, without relinquishing objectivity; the ad spot, meanwhile, reaches out for “legalistic justification” for its message of relevance by “get(ting) us in the gut.”13

This raises the question of the historical place of fear-control in the media discourse of alien threat. In his work on the US government’s management of fear in post-nuclear America, Joe Masco argues that government propaganda films from the 1950s systematically scripted an American response to nuclear threat, targeting audiences for education in ways that carry forward to this day the idea that extreme scenarios, from the “war on terror” to weather disasters and the effects of global warming, can be and are being managed; further, that civil obedience has ecological as well as human-nature-controlling rewards.14 Effectively setting out the “American Way of coping,” he writes, “fear becomes the basis for both a new concept of global order and a new kind of American society—simultaneously militarized, normalized, and terrified.”15 For all intents and purposes, then, these films’ psychological fear-control strategies position the US government as an all-knowing professoriate. The “character armored”16 professor of the Farmer’s Insurance is its personification, in extending his lesson to the commercially “manageable” realm of cosmic exo-surprise.

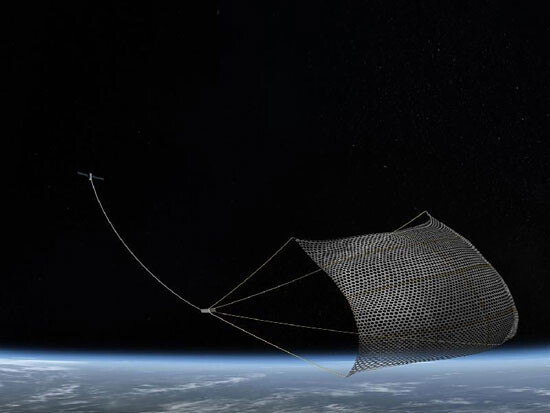

A further declension of state projects of citizen-making characterology, the contemporary media that I’ve been observing here would appear to be fashioning a new narrative for the new world order out of space debris which has taken on a life of its own beyond mere mortal control. This emergent narrative is a dangerous one of resignation to cosmic forces and inevitabilities. Senior NASA scientist Donald Kessler put it this way: “We’ve lost control of the environment.”17 What remains, it appears, is to plan for the worst-case scenario and valorize tracking technologies and hyper-vigilance.18

In contradistinction to marketing models and against the grain, too, of reportage, governments are charged, then, with generating awareness, while undoing, as effectively as they can, relevance: the aerospace gods might be crazy but their governments are victims of the random vicissitudes of “space weather.”

I lived this new consciousness over the span of three days when I was perched at my computer desk (next to a wall of floor-to-ceiling windows) as the fiery descent of the thirteen-ton Phobos-Grunt Mars probe was lighting up network news. The first projection was that it would fall to earth “somewhere between 51 degrees north and 51 degrees south”; then, a couple of pages on in my writing of a draft of this paper, on or near Madagascar; then, as I was cleaning up the introduction, on or near The Falkland Islands; then, as I was taking a break for Chinese food, on or near Argentina, until on the projected day of impact, January 15, 2012, I could read on the online Daily Mail that “experts admit they have no idea when and where it will hit … due to constant changes in Earth’s upper atmosphere, which is strongly influenced by solar activity.” The end was announced shortly thereafter: Phobos-Grunt had vanished from tracking screens somewhere south of Chile, probably in the ocean, but not on New Zealand.19

It is not surprising to learn that launch nations are insured for damage claims, although like any insurance policy, there are loopholes. Famously, the folks of Esperanza, a tiny town in northern Australia, finally had to resort to sending NASA a ticket for “littering” when in 1979, parts of the Skylab space station crashed into their township.20 And when a piece of space debris from a Meridian satellite that was launched from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan demolished part of a house on Cosmonaut’s Street in the village of Vagaitsevo in Siberia (a husband and wife were at home but were miraculously unharmed), the owners had to content themselves with the Russian government’s promise to make full reparations.

In sum, the post-nuclear fear-control narrative that continues to influence American life has, under hyper-corporatization and hyper-mediatization, given way to a narrative of inevitably misbehaving entities. Detached from controlling powers, “junk happens” in the naturally hostile environments where it belongs. This dangerous unmarked elision makes use of the gap between accidents in space that can produce “Iridium,” and “The Chinese” intentionally working in mysterious ways, for perversely spinning a new narrative from the elements of “cosmopolitics,”21 and what Latour appreciates as its conceptual work: that “cosmos [will] protect against the premature closure of politics, and politics against the premature closure of cosmos.”22 This new spin would have cosmic force-fields and their entities colluding with accelerationist politics as if their partnership were written in the stars of consumer-citizens.23

In this scenario, to borrow terms from Noys,24 Cold War “affirmationist” narratives lose their grip on the imagination, as do injunctions to “surge forth” against destructive forces of hyper-extraction-affirming ways of life. And while relinquishing designs on cosmic sovereignty may be an entailment of the resignation narrative, this script sets itself apart from corporate designs on outer space colonization. So how could an aesthetic so baldly in service to the accelerant of revved-up capitalist expansion leave me feeling so uncannily out of place in its presence—as if the crisis were permanently elsewhere and elsewhen?25

Again, the point to emphasize here is the relation between what appears to be the matter—namely, things coming literally out of nowhere which threaten prevailing social orders with evidence of their vulnerability—and the greater danger that public attention to space junk will mask the multinational technologies of militarism to which insecurity actually sources. Beyond this, alarming images of dangerous blindsides—media artifacts of false witness to the long, slow, and still unfolding narrative of the military-industrial misalliance—deny space debris discourse its historical contexts of production, deny it any affinity to a rhetoric of accelerating threat, and too, deny it any kind of social future … other than as science fiction: as I prepare to hit the “send” button to deliver this piece for online publication, advertising embedded within the frame of an animated “space junk awareness” infomercial produced by the European Space Agency on space.com intertexts an ad spot for Star Trek IV: Into Darkness and one for Esurance.com, where we watch as the starship Enterprise is accidentally run into by a space vehicle from another planet, jolting the crew and sending sparks and objects flying. The offending driver apologies via the ship’s communication screen and the two parties enter into a civil conversation about what just happened in outer space.26

De-Accelerating the Accelerationist Real

If a take is lengthened, boredom naturally sets in for the audience. But if the take is extended even further, something else arises: curiosity.

—Žižek, referring to Tarkovsky27

Enter a third media treatment of space junk, which is that of painstaking documentary description, and what might be thought of as the socioaesthetic mode of dawning curiosity. Sliding around the problem of being an art form, the documentary can refuse any idea that, as Shaviro puts it, “art restores potentiality [to enunciate utopia] by derealizing the actual.” Shaviro raises the concomitant issue of whether this is “still practicable, in a time when negation and counter-actualization have themselves become resources for the extraction of surplus value”: it is.28

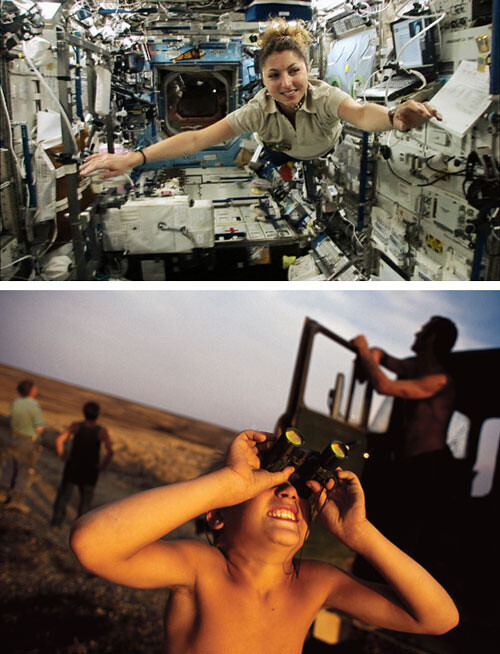

Upon learning that I was an anthropologist, a space law expert at the Prague space security conference insisted that I view the ethnographic documentary film, Space Tourists (2009). Of course I ordered it immediately. The cover of the video box I received foregrounds a young shirtless boy with binoculars trained at the sky. In the background, bronzed men in T-shirts look towards the stars. They are scanning for signs of freshly fallen space junk. But this is not the prevailing online cover image, which features, in the style of Soviet realism, the first tourist of outer space, Anousheh Ansari.

The story of their different worlds is told collaboratively in sharply contrasted cuts between scenes of the preparation and journey to the International Space Station of Ansari (“cost: 20 million US dollars”) and the long, slow takes of the daily lives of impoverished scrap-metal dealers in Kazakhstan, who labor secretly to scavenge the booster stages that fall to earth following rocket launches from Baikonur Cosmodrome. The filmmaker, far from capturing the action disinterestedly, narrates his implication in it as one who has himself traveled from sites of elite culture to sites of rural poverty and across international and cultural boundaries, placing him in a position to translate the starkly different realities he looks into, not at.

Against scenes of Ansari’s self-assured excitement, her high design space suit, her mother in Chanel sunglasses excitedly watching the moment of liftoff, the rocketry which transports her into the sublime cosmos of her dreams, are scenes of the dulling, tedious work of scrap-metal rendition. The material realities of the dealers’ lives appear in low-action, “just-the-facts” images: a rudimentary house, vodka, bread, cigarettes, toast, a man welding a horseshoe onto the huge ugly truck that joins a convoy to the collecting fields of space junk, sending up dust in its wake, a couple staring at an old television where the launch coverage is being broadcast. Then, Ansari: “How can you put a price on a dream?” Cut to the driver of the truck: “We’ll get the job done,” as he turns his jerry-rigged vehicle towards the spot where a booster has landed, setting off small grass fires. We see the burnt carcass of an animal. There is a large amount of chemical residue in these boosters, we are told; it must be drained off. We see this. But there is also high-grade aluminum alloys and titanium, which can be sold to China. Cut to the ISS where Ansari is playing with balls in weightlessness, brushing her teeth, commenting on “an Earth without borders … no sign of trouble, just pure peace and beauty.” The scrap renderers pull out a chain saw and start cutting up the rocket, pull out knives and start slicing a potato for a stew in a pot made from a part of the rocket. Ansari eats rice from a little can. On the ground and two thousand miles farther north, we hear, is a more densely populated area; sometimes rockets fall on houses there, including proton rockets fueled by hepton, “a known carcinogen and fairly toxic chemical.” Ansari is playing with globules of airborne water.

Effectively, the filmmaker has interrupted the violence of the montage, not for communicating a testimonial to an imperfect scientific ontology, but for creating breathing spaces grabbed from the ground of an alternative episteme that casts natural spaces as becoming-generic ones. It is as if, taking a cue from Moreno on Deleuze’s conception of any-space-whatever, the entire earth, and not just built environments of capitalism’s great mall-ist structures, have been “unplugged from ‘that which happened and acted’ in it … thus dismantling established orders, and clearing the way for unexpected and latent potentials to be actualized.”29 Except that this is a post-Soviet landscape, documented by the aesthetic devices of sharp cuts and slow takes pioneered by the two giants of Russian cinema, Eisenstein and Tarkovsky, respectively.30

If the “elephant in the room” at the Prague space security conference of 2011 was the threat to global life and security of international brinkmanship, in Space Tourists it is the phenomenal accountability gap between the worlds of the few globally rich who position themselves stratospherically above the many locally poor: the one world’s cosmology, as David Valentine recognizes this,31 shielded by faith in its own imaginary, whilst the conceptual and material debris of that dream supplies a groaning ethnoscape with happenstantial resources. Other than by the magic of montage, these worlds have no prospect of coming into direct contact, and even in the film they aren’t made to impact one another forcefully: the film puts itself in the way of this. Indeed, it is precisely by mise-en-abyme referencing of the absence of the velocity of impact of these worlds that the ethnography marks the extreme trending of their otherness to each other. Refusing an accelerated aesthetic that feeds on crisis, and also a narrative of resignation to control by The Powers That Be, the film documents the insufficiency of both for delivering the sense of cosmic exo-surprise as an invitation to make worlds differently than by imploding futures.

***

Is it naive to conclude on a point of hope? In contradistinction to art’s despair of ever finding a stable position that holds against the disruptive cultural and natural force-fields shaping the contemporary moment,32 ethnography concretely engages perspectival instability, which it approaches as an open invitation to epistemic inquiry for addressing what gets in the way of connecting across difference. Offering an alternative to fabrications which trade on the “intensity effect,”33 as both space junk ad spots and reportage do in what Moreno recognizes is a kind of “ingratiating aesthetics in service of [capitalist] acceleration,”34 the documentary’s dawning effect supports socioaesthetic transformation over rupture, tethering the accelerationist romance with violent excess to the very bricolage material it draws from—but with the value added of a future in cosmos.

See →.

Noys’s discussion of “la politique du pire,” in his The Persistence of the Negative: A Critique of Contemporary Continental Theory (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2010), places this in a broader context.

Gean Moreno, “Notes on the Inorganic, Part II: Terminal Velocity,” e-flux journal 32 (February 2012). See →.

Battaglia, “Coming in at an Unusual Angle: Exo-Surprise and the Fieldworking Cosmonaut,” Anthropological Quarterly Vol. 85, No. 4 (2012): 1089–1106.

Joseph Masco, “Target Audience,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Vol. 64, No. 3 (2008): 22–31.

Compare Andrew Arno, Alarming Reports: Communicating Conflict in the Daily News (New York: Berghahn, 2009).

Noys, The Persistence of the Negative.

See →.

Kenneth Chang, “Satellite’s Fall Becomes Phenomenon,” New York Times, September 22, 2011. See →.

See →.

Mazzarella, “Affect: What Is It Good For?,” in Enchantments of Modernity: Empire, Nation, and Globalization, ed. Saurabh Dube (New York: Routledge, 2006), 299.

Ibid. For expressions of what Deleuze terms “the control society” (Deleuze, “Postscript on the Societies of Control,” October 59 (1992): 3–7) one need look no further than “the relentless marketing and ‘branding’ of even the most ‘inner’ aspects of subjective experience,” as film theorist Steven Shapiro insightfully puts it in his Post-Cinematic Affect (London: Zero Books, 2010), 1.

Masco, “Target Audience”; and Masco, “Bad Weather: On Planetary Crisis,” Social Studies of Science 40 (2010): 7–40.

Masco, “Target Audience,” 31.

The term is psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich’s.

See →.

Of course, behind the screen, as it were, mechanical solutions are being sought and even found. See →.

See →.

See →.

Isabelle Stengers, Cosmopolitics—Volume I, trans. Robert Bononno (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010).

Bruno Latour, “Whose Cosmos, Which Cosmopolitics?: Comments on the Peace Terms of Ulrich Beck,” Common Knowledge Vol. 10, No. 3 (2004): 454.

See Latour’s comments on Stengers’s concept in Latour, “Whose Cosmos, Which Cosmopolitics?”

Noys, The Persistence of the Negative, 54.

See →.

See →.

Žižek, “Hegel Versus Heidegger,” e-flux journal 32 (February 2012). See →.

Shaviro references what he takes to be the shared vision of Deleuze and Adorno on the topic of modernist art. See Post-Cinematic Affect, 163.

Gean Moreno, “Notes on the Inorganic, Part II: Terminal Velocity.”

Ironically, it is Eisenstein who speaks of studying over and over again the ethnographic film Nanook of the North—the film that inspired the coinage of the term “documentary” in the popular press, and which is all but an homage to long takes of everyday life events in out-of-the-way places, from its collaborators’ point of view.

Valentine, “Exit Strategy: Profits, Cosmology, and the Future of Humans in Space,” Anthropological Quarterly, Vol. 85, No. 4 (2012.): 1045–1067.

See Shaviro’s discussion of the issue in the context of “ubiquitous digital technologies,” Post-Cinematic Affect, 131.

Shaviro, Post-Cinematic Affect.

Personal communication.

My appreciation to Abou Farman and Gean Moreno for their insightful comments on earlier drafts of this paper.