Can we make art after we die? What are the possible media for an art of the afterlife? To consider the possibility seriously is not to revisit work that deals with grief and dying, or with the mere representation of the afterlife. It is not to ask the disenchanted to return to the open arms of the Church.1 But it does require that we reexamine the limits around our ideas of transformation; it does require that we parse “the secular” as the background code that determines the parameters for many of our activities and assumptions.

Whatever our private beliefs today, the secular code—or the “Secular Age,” to use Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor’s better-known designation2—forces us into this consciousness, this disposition: we believe we are, in some real sense, going to die.3 Of course, everyone in every other age had a similar intuition, but not the same experience of it. This difference hinges on orientations towards the afterlife. (It is crucial to emphasize that, unlike secularist interpretations of them, doctrines of the afterlife do not deny death; death is precisely their condition of possibility. It’s what happens afterwards that is the real issue.)

The historian Jacques Le Goff has documented how the invention of purgatory in the ninth century produced a radically new experience by changing the absoluteness of the ending.4 In those days, judgment came right at the time of death. After mere decades of waffling through life, suddenly you faced the prospect of eternal damnation. That’s tremendous temporal pressure, and the doctrine of purgatory was invented as a sort of release valve. Saints and sinners were sorted out right away, but the rest of us who are a sausage of saint and sinner (to use Charles Simic’s Eastern European formulation) could at least loiter around a while longer and get our surviving family members to intercede on our behalf. Because of what could be done on your behalf by others after you died, you were, in a sense, not done being, or your being was not done with.

In the secular age, the default assumption of finality is not so different from the pre-purgatory version of death, minus the judgment. Some might go to church on Sunday and believe they will end up in heaven, while others might believe they will survive by joining some universal consciousness or Noosphere. But secularism has privatized belief to such an extent that, outside of Sundays, very little of this sort of thinking is institutionalized in wider educational, legal, or state spheres.5 It is permitted insofar as it is privately held. Even for those who believe in life after death, the possibility of a person remaining active as an agent in this world after his or her death is outside the realm of possibility; their lives are not inflected by either the decisions, desires, and doings of the dead, or their own post-mortem plans.

This possibility is eliminated by the generalized rules of secular life-death regimes, which impose a specific temporal order on the body and the person ascribed to it. Secularism is generally understood in terms of the doctrine of the separation of powers between this world and the next, between church and state. But as the anthropologist Talal Asad has argued, a set of background assumptions, dispositions, and epistemologies create the conditions of possibility for this secularist separation, grounding its discourse of justification and systems of thought, producing its selves and experiences, its temporalities and rules of conduct.6 This is what distinguishes the secular from the religious and the supernatural. The play between the secular and the religious has always turned on an important set of rules having to do with the relationship between person, body, and identity—especially at the crisis point of death.

In a secular order, a person—as a locus of rights and interests, as a possessor of consciousness—is separable from the body. That is, social status and political rights accrue to a rational, willful, and conscious entity with interests, not to an organism or a biological body (which means that the secular is dualistic, but in a rationalist way: it’s a dualism that does without the concept of a soul). This is what allows for formulations such as “corporate personhood” or “brain death,” in which the body is kept biologically viable (or alive) for the sake of its organs, whilst the person who formerly occupied the body is declared dead by the secular medico-legal regime.7 However, within a secular frame, this separation is unidirectional: whereas the secular body can outlive its person, the secular person cannot outlive its body. The latter would be read as religious, or as a cognitive error locatable in the angular gyrus of the brain.

This is the ideology, or the code, of the Western secular tradition. Why ideology? Because beneath the discourse and formal rules, there are ways in which persons are allowed to quasi-survive their date of biological expiration. The most obvious is through personal objects of memory, those things which resonate with the accumulated traces of the deceased’s life, and which cause intense reactions in surviving loved ones. People are thus permitted to believe that the deceased in some way survives in these object, whose animistic power we tame by calling them “objects of memory.” But this sort of interaction is permitted only as long as a) it is understood that the force does not reside in the objects but in the survivor’s head, and b) this belief does not last too long (hence quasi-survival). Sustained, long-term relations to objects that evoke strong emotions and attachments are pathologized and interpreted through the idiom of mental disorder; the role of the psychiatrist or counselor then becomes that of de-animizer, removing the spirit from the inanimate objects so the bereaved patient can achieve “closure.”

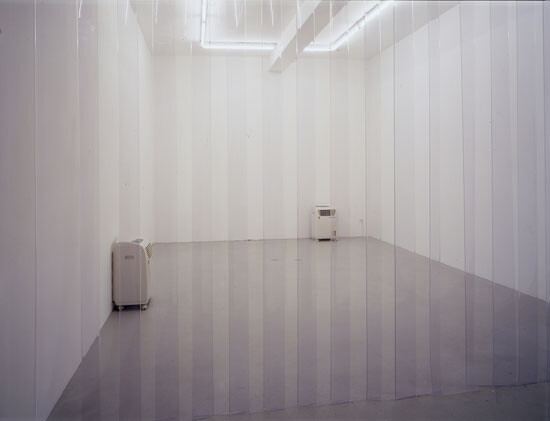

Significantly, another secular domain that functions as a de-animizing force is the museum. Ethnographic museums, which were among the earliest museums, were set up with this function explicitly in mind—to take “the primitive fetishes” and reveal them as nothing but objects. This was accomplished through strategies of display and archiving.8 But this function is not just a colonial one; it is generalized to all objects in museums. No one cries upon seeing an heirloom in the Met, even if it belonged to one’s own family. Another ideal-typical example of this phenomenon is the perfectly archived possessions of Song Dong’s deceased mother at MoMA.9

There is room for quasi-survival in secular law as well, where the law allows some intentionality and agency, some ability to act, after the bounded, conscious, sovereign self has medico-legally expired. Take the last will and testament. This a legal formalization of the deceased’s “will,” that is, the “power to decide” or “the part of mind that makes decisions.” This faculty is what defines secular personhood: when it is lacking—for example, when someone is in a coma—that person is not considered a full person. His or her decisions are then carried out by the family or agents of the state.10 Yet, this will—this power to decide, this part of the mind—is allowed to legally survive the end of bodily death. In a secular world, where the dead are supposedly dead and gone, we are nevertheless bidden to respect the desires of the dead. The dead, then, have a will. They have desires and they have interests. And as legal scholar Ray Madoff has documented, the rights and interests of the dead are growing daily in the US.11

Artists and collectors have only ever used their legal wills for conventional purposes—foundations, donations, estates, supporting their friends and family, protecting their works, and so forth. As far as I know, the legal will has never been taken up as artistic form. This, I am suggesting, is due to a bias in our secular code that has blinded artists to the possibilities of making art after they die; after death, the assumption goes, the artist is no longer present. What if we conceived of the afterlife as having the potential for continued agency after bodily demise, an agency not confined to the body but activated in and by others and other things—what anthropologists call “relational personhood”? Then we might also ask about the media available to the artist seeking this mode of survival.

Let me try and get at this from the angle of biopolitics. Foucauldian biopolitics describes a shift in techniques of governance, where instead of just wielding exemplary death—public hangings, occasional slaughters, arbitrary slayings—the state begins to manage the health of the body politic.12 The interests of the sovereign state and the sovereign individual coincide more and more, such that the health of one corresponds representationally and materially to the health of the other. The grounds of this conjunction is biological life itself. We thus get the emergence of the clinic, departments of health, morbidity and life expectancy statistics, mandatory physical education, gyms and other disciplines of the self through which the body and subjectivity are monitored and shaped.

I am interested in biopolitics because it also marks a secular shift—a this-worldly turn in governance. The imagined spaces of purgatory and heaven and hell, the journey of the soul and the afterlife, are foreclosed as organizing socio-political forces through which people are shaped as ethical beings seeking fulfillment. Judgment and justice become matters necessarily organized in a real space called this world. The same thing happens to happiness and health—the conjunction of which gets enshrined in what we call a “constitution,” a term that turns the original biological meaning (“one’s general condition of health”) into a country’s fundamental laws governing the well-being of the nation. Hence the enshrinement of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness as the trinity of earthly activity.

This leads relatively directly to what many today term “the culture of life,” where life itself—bare life or life as matter—becomes the locus of sociopolitical and aesthetic intervention.13 In the twenty-first century, biotechnology is clearly the big embodiment, so to speak, of all this. Biotech: not just as a lab technique dealing with immortal cells, cloning, and stem cells, but also as utopia, as imaginary, as the model and language through which we understand our existence.

What this has meant aesthetically is, on one level, obvious: we get Eduardo Kac’s green bunny, and live birth in an art gallery.14 Put another way, biology and art collapse into each other, only to reveal each other as modalities of copying. DNA, the original copying machine, is now the perfect medium for art. With a quick cheek swab and the click of a mouse, you can ask clever companies to turn your DNA sequences into a “self-portrait” to hang above your bed.15 The age of mechanical reproduction regresses into the age of biological reproduction, taking commodity fetishism to the level of what Eugene Thacker called “biocapital,” where the social relations of production are between you and your DNA, those cellular proletarians laboring to produce you from the inside out.16 Because of all this focus on life as matter, the very other of life has fallen into neglect. But think what your DNA might be able to do after your so-called death!

A great deal of the art that gave rise to the modern institution we call “the museum” was death-related, funerary art (especially mummies displayed at the British Museum in the eighteenth century), or else artifacts from dying cultures (including collections from defunct monarchies or regimes). Gillian Beer reminds us that with the popularization of Darwinism, extinction—as central to Darwin as survival—was a prominent concern in Victorian culture, echoing new worries about a death without the afterlife.17 Modern secular cultures totemized artifacts of extinction and survival in museums—on the one hand, as emblems of their own ascendance and progress, images of their own survival as the fittest; and on the other, as a displacement of their new worries about dying and not dying, which they handled by objectifying death. The modern attitude was to view the afterlife as an illusion, appropriate only for atavistic collection and display. It bears mentioning that memorial monuments came about at the same time as museums. The original Nelson’s Column-type celebration of triumph in war was biopolitically turned into a commemorative monument to remember the the nation’s fallen sons.18 Memorials are built in response to collective trauma, as the nation-state’s shamanistic act of exorcising bad spirits. Memorials, like museums, house both extinction and survival.

When museums added the qualifier “modern” to their purpose—“art”—they wanted to mark a shift: from that which was extinct or slated for extinction, to that which is being created now. The terms “modern” and then “contemporary” signified an increasing distance from death, like the circles of the inferno moving backwards. So the modern art museum came to store the activity of people who were not dead. But there is no doubt: it did so in preparation for their deaths. The artist’s labor now becomes a fetish kept in this storage pod “for posterity,” like the pinkie of a saint, like the foreskin of Jesus. Collecting “work” made by people who were not dead, but doing so in anticipation of their deaths, museums of modern art were already claiming the artist as relic, as corpse. Ironically, they and their collectors produced the artist as a category of the living dead, valued for his or her “remains,” the remains of his or her labor.

In the absence of notions of personal survival, art is one of the better vehicles for leaving a trace beyond a solitary finite existence. This is a prominent worry in secular psyches, which is why Woody Allen’s quip always draws a laugh: “I don’t want to achieve immortality through my works; I want to achieve immortality by not dying.” The museum is a secular place for the first kind of immortality, a place where your work survives when you don’t. That is precisely the nature of the exchange. Thus the perfect show, title and all, for this secular age was the New Museum’s Younger Than Jesus, fetishizing artists younger than Western civilization’s greatest sacrificial figure, turning life into death at thirty-three, and invoking resurrection as the ideal of a continuous life project of staying young but nailed to a museum wall.

I don’t presume to propose an antidote to this cannibalistic consumption of live art. But can’t we get away from the myopia of life itself? Are there media that can be used for afterlife art, for an aesthetics whose imaginary and field of practice might be called “post-secular”? Where can we find clues?

A number of artists have consciously approached this territory, but have stopped short at the boundaries of the secular. An example is Theresa Margolles, with her work using water from a morgue. The water used to wash corpses has touched the dead, mixing with the corpse. She then uses the water to generate vapor or bubbles in a gallery space. The repulsion and fear she triggers in the audience questions the secular notion of a corpse as inert matter, and of the dead as without any causal effect in this world. The dead here have measurable, physical causal effects on the living. The only trouble is that they are anonymous. It is not a specific person whose agency is felt by the audience; rather, the work produces a charged environment that triggers generalized phobias around death.

In another register, Jae Rhim Lee, a Korean-American artist, has started The Infinity Burial Project. She has developed mushrooms that will help decompose your body in such a way as to get rid of all its accumulated environmental toxins. So instead of your dead body poisoning the earth, it will enrich it. She has designed a Mushroom Death Suit, carrying mushroom spores that are activated on burial. The best thing about her project is that people have agreed in principle to donate their bodies after they die. She is using other afterlives as performative and experimental substance. However, she frames her work in terms of a typical notion of a corpse, embracing the secular aesthetic that says: Accept death! You are done as a person! You have become a post-mortem body only! Her project is thus an environmentally friendly mortuary ritual—which is a popular practice of its own these days, called “green burial.”

The musician and performance artist Genesis Breyer P-Orridge provides an interesting counterpoint—one that actually starts in the creation of a new form of life-before-death. Genesis came to the East Village in the early 1990s after years of making experimental art in England as a member of Throbbing Gristle and Psychic TV. In the US, he fell madly in love with Lady Jaye, a practicing nurse, dominatrix, and musician. In their blissful, dedicated union, they decided they wanted to merge—not so much to become one, but to create a third, other being made of the two of them joined beyond social identities, a being they called a “pandrogyne.” They both underwent radical plastic surgery to begin to resemble each other. The exterior changes were not, as Genesis emphasizes, superficial. Extreme physical changes affect the psyche, and increasingly the two did look, feel, and act like a single pandrogyne. Then Lady Jaye died—or as Genesis terms it, “She dropped her body, the cheap suitcase.” You can imagine Genesis’s sadness. But you can also imagine how the original merger in life provided a new possibility for not dying, for being preserved in and as the pandrogyne. But Lady Jaye has survived as an agent in even more interesting ways. Genesis says, “One of us is technically dead, but she’s involved in everything I do … We’re still working together and the things we create couldn’t have happened without her presence.” Indeed, Genesis is inhabited by an assemblage of agencies, no longer even using the first person pronoun. If language is a measure, s/he has deictically shape-shifted. That’s one way to conceive of post-secular aesthetics, one in which an assemblage of things—including people in their parts or wholes—are enlisted in the activation of distributed, substrate-independent agency.

There has been a recent tendency—mostly by non-artists—to have some artistic fun with death by designing customized coffins and tombstones. Whilst this is clearly not what I mean by afterlife art, one outcome of this tendency has intriguing potential. A number of companies, such as QR Memorial, offer new QR-encoded tombstones. What if instead of showing old photographs and videos, these were to activate self-regulating, evolving, and interactive avatars? Perhaps avatars that already exist and have been active in other spaces, such as World of Warcraft or Second Life? Currently, every movement and interaction made by a player in WoW is recorded. Thus the avatar captures a relational or social self.19 The avatar self can outlive its humanoid player (or agent) and continue functioning as what is now being called a “non-player character (NPC).” Researchers are trying to make NPCs behave more like specific people on their own, without a human agent behind them.20 The avatar-person that survives the body-person can then continue relations with others through a QR-activated pocket-sized “tombstone” (like an afterlife Furby), thus challenging one of the key secular rules of personhood. A minor version of this is already available for the Twitterati. If you sign on to the website Liveson.org, you can have their algorithms analyse your tweets in order to learn “about your likes, tastes, syntax.” Your feedback in this process will help the algorithm develop a “better you.” The algorithmic you “will keep tweeting even after you’ve passed away.” Their branding jingle is: “When your heart stops beating, you‘ll keep tweeting.”21 That is closer to what I am calling post-secular aesthetics.

Returning to the original body of flesh, it is worth noting that people regularly donate their biological bodies to afterlife adventures, but because this act is mediated by science, it is not glossed as performative. Yet, when bodies are donated to scientific research, they become, in their afterlives, all sorts of cool things: from crash test dummies to functioning organs in other people’s bodies to clumps of cells growing in tissue culture. The specifics are sometimes left up to the donor, who can, for example, donate directly to an organization, such as Bodies: The Exhibition. But in such cases—as in all donation—there is a major problem: anonymity. The Bodies exhibit, for example, will not associate any specific parts of you with your name or personal identity. You might become a cornea in a running back, or an index finger in a poker player. People in the Bodies organization have told me they regularly receive requests asking that a donor’s identity be made public in the exhibit, but the company ignores these requests. Your body is on display, not your person. Indeed, the entire organ donation system works on the basis of anonymity, since the medico-legal regime does not want to encourage the continued life of one person inside another, despite the fact that many organ recipients and family members of donors restructure their senses of self, feeling, and behavior as though some aspect of the dead donor is active in a new hybridized body.22

But the anthropologist Lesley Sharp has documented patient activists who are trying to change the anonymity rules.23 As a result, organ donation is now a promising afterlife art medium. Artists could use the power of organ donation laws to exert personal agency after secular law has declared them dead. One way to do this would be through other bodies. For example, imagine an eyebank full of artists’ eyes. One pair might have belonged to David Hockney. Perhaps Marc Glimcher, the director of Pace Gallery, which represents Hockney, could bid to have them implanted in himself, and so begin to see the world through Hockney’s eyes. Maybe he’d stop collecting.

The legal will is another potential afterlife medium. Rather than use it simply as a way of devolving estates, artists could use it to guide action in the future. Emily Jacir could sell her legal will, or a part thereof, as art to the Guggenheim. She could insist in the will that, for example, Nancy Spector, or her equivalent, make an annual pilgrimage to Haifa and return with a briefcase full of Palestinian earth which, diluted in some Poland Spring water, should be drunk by all members of the board at their annual meeting. There is precedent for this. Charles Whitmore, a lifelong hiker, requested that his ashes be spread on 315 peaks in southern Arizona; at last count, Whitmore’s remains had been spread on 176 peaks by hikers from his club, who were working on the remaining 139.24 Indeed, Mr. Whitmore is a great post-secular performance artist.

Some further possibilities are suggested by my own research as an anthropologist working with Immortalist groups, who want to achieve physical immortality through scientific means—through Artificial Intelligence, molecular biology, and cryonics. Terasem is an organization based in Satellite Beach, on the space coast of Florida. Its founder, Martine Rothblatt (née Martin), is a transgender lawyer and inventor who was a pioneer of the satellite vehicle tracking and satellite radio industries, including Sirius. Martine is also the founder and CEO of United Therapeutics, a biotechnology company, and the author of several books, including The Apartheid of Sex and Unzipped Genes. Terasem and Rothblatt have teamed up with William Sims Bainbridge, a social psychologist and a director at the National Science Foundation, on a project called CyBeRev. The two are founding members of the “Order of Cosmic Engineers,” whose goal is to “permeate our universe with benign intelligence, building and spreading it from inner space to outer space and beyond.”

CyBeRev has been collecting “mindfiles”—digital files that represent your mind. The information is gathered from participants based on a psychological profile form designed by Bainbridge. The form is meant to elicit as much useful information about you as possible, so you can be reconstituted by a superintelligence in the future. Participants can choose to include additional information as well, such as photographs, data files, and scanned journals. The more complete the file, the better it will approximate you.25 The mindfiles are then “spacecast”—transmitted as digital information via satellite into outerspace. Rothblatt says, “Every Terasem joiner or participant who has mindfiles with us has already achieved a certain level of immortality by having aspects of their mindfiles already anywhere from up to five to six light years away from the earth depending on when they started uploading.” In other words, there is no reason why “you” couldn’t be making art, or unfolding as an art piece, near a red dwarf star after your earthly demise.

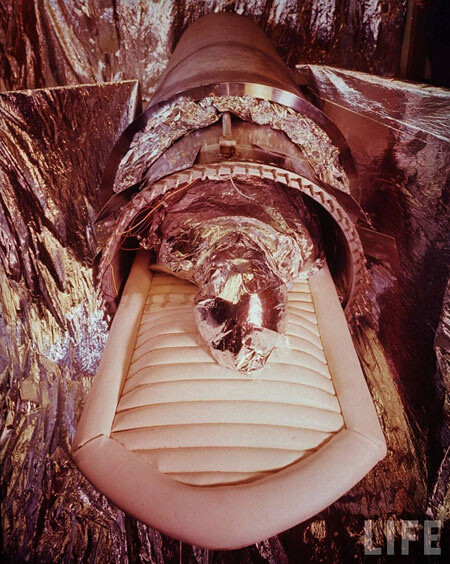

In closing, let me turn to cryonics, which abides no final endings. Cryonicists argue that death as presently defined and administered is merely a placeholder for the limits of our primitive knowledge. Death is nothing more than a medical and legal convention. The process of biological death is a cascade of events that takes much longer than we assume. There is a much wider window for intervention between the onset of these events and the accumulation of final and decisive damage. Cryonicists believe that if they can immediately stop further decay of the body and brain, future science will likely find a cure for the affliction we currently call death. In order to do this, their members are cooled down as soon as legal death is declared, and they are stored, or suspended, in gleaming vats of liquid nitrogen called “cryostats.” In there, all metabolic and biochemical processes are halted at minus 196 degrees Celsius, a temperature at which virtually nothing happens. But since this is a matter of life and death, it’s best to be precise about how much nothing actually happens: biochemical reactions that at a normal 37 degrees Celsius occur over a timespan of six minutes would, at a temperature of minus 196 degrees Celsius, take 100 sextillion years to unfold.26

In this example, the choice of a six-minute timescale is not random. Conventionally, six minutes is considered to be the time it takes after cardiac arrest for ischemic damage to result in final brain death. For cryonicists, biological time is elastic time: you can stretch it, and if you get into a cryostat quickly enough—right after the properly authorized person pronounces death—and you stabilize the body, cooling the head and circulating blood and oxygen so that brain cells and organ cells remain alive, you can eventually, perhaps, expand that six-minute window into … 100 sextillion years. One cryonicist told me, “It’s like hitting the pause button.”

In the meantime, all those people on pause, in their liminal state of suspended animation, cannot be treated as mere corpses. They are regarded as having future potential lives. Secured under lock and surveillance camera, they are called “patients.” They have patient numbers and patient files. They are treated as quasi-people with rights, people worthy of protection and care, people with a life waiting for them in the future. Perhaps.

Rather than its mechanics, think of the poetics of this act of not dying. Perhaps as a cryonically frozen body you are not ultimately recoverable. But perhaps you are. After all, hundreds of people have survived “clinical death” after, for example, drowning in frozen rivers.27Every year hundreds of patients undergoing cardiac surgery are deliberately taken down into “cold death”—no heartbeat, no circulation, no brain signals, body temperature a little above freezing. And then, having been legally dead for an hour while their non-beating heart was repaired, they are brought back to the surface, to this thing we call consciousness. As one heart surgeon told me, “We take them down to death. We just don’t call it that.”

I am not trying to convince you of the scientific possibility of cryonics, but of the poetics of that “perhaps,” the poetics of the space of suspension, in which return is not the issue at all. It is the sheer possibility, the liminality of it, the openness and suspension that matters, along with the unanswered and perhaps unanswerable questions and fears that are activated in the encounter.

I think, then, it would be fitting to start a cryonics museum. It would free us from making art altogether. All we’d have to do was die under the right circumstances and be stored properly, still full of potential, nothing but potential…

This is a phrase resurrected from Max Weber’s essay on disenchantment, “Science as a Vocation” (1946), in which he sardonically offered the bosom of the Church to the modern, disenchanted self. Suggesting that such a return was not feasible, he told his audience that the man of science had to suck it up and stoically continue doing his work despite the meaningless present and the already-obsolete future.

Charles Taylor, A Secular Age, (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard Univ. Press, 2007).

We are reminded of this in a video piece by the Chinese artist Yang Zhenzhong called I Will Die (2000–2005). It shows a series of faces looking straight and emotionless into the camera, repeating one after the other the same natural fact: “I will die. I will die. I will die.” The seriality of the faces in linear time, each declaring an absolute end, collapses individual subjective time into the eternal time of nothingness, in which none of the people in the video—none of you, none of us—will exist. Under their cumulative weight, the banality of individual finitude turns into a sense of horror in the face of nature’s holocaust.

Jacques Le Goff, The Birth of Purgatory, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984).

On public and private religion see José Casanova, Public Religions in the Modern World (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994); and Talal Asad, “Trying to Understand French Secularism,” in Political Theologies: Public Religions in a Post-Secular World, eds. Hent de Vries and Lawrence E. Sullivan (New York: Fordham University Press, 2006).

See Talal Asad, Formations of the Secular: Christianity, Islam, Modernity (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2003).

See Beth Conklin and Lynn Morgan, “Babies, Bodies and the Production of Personhood in North America and a Native Amazonian Society,” Ethos Vol. 24, No. 4 (1996): 657–694; and Margaret Lock, Twice Dead: Organ Transplants and the Reinvention of Death (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002).

Some of these ideas, especially in relation to the colonial encounter, were covered by Anselm Franke’s show and comprehensive catalogue Animism (Franke 2010). They were further elaborated in e-flux journal 36 (Summer 2012). See →.

See →.

See Sharon Kaufman, “In the Shadow of ‘Death with Dignity’: Medicine and the Cultural Quandaries of the Vegetative State,” American Anthropologist Vol. 102, No. 1 (2000).

Ray D. Madoff, Immortality and the Law: The Rising Power of the American Dead (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011).

Michel Foucault, The Birth of Biopolitics: Lectures at the College de France, 1978-1979 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008); and Foucault, Discipline and Punish (New York: Vintage, 1999).

See Karin Knorr Cetina, “The Rise of a Culture of Life,” European Molecular Biology Organization Reports, Special Issue, Vol. 6 (2005): 76–80.

See, for example, →.

Eugene Thacker, The Global Genome: Biotechnology, Politics, and Culture (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005).

Gillian Beer, “Darwin and the Uses of Extinction,” Victorian Studies, Vol. 51, No. 2 (2009): 321–331.

See Reinhart Kosselleck, “History, Histories and Formal Structures of Time,” The Practice of Conceptual History: Timing History, Spacing Concepts, trans. T.S. Presner et. al. (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2002); and Jay Winter, Sites of Memory, Sites of Mourning: The Great War in European Cultural History (London: Cambridge University Press, 1995).

See William Sims Bainbridge, The Warcraft Civilization: Social Science in a Virtual World (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2010).

See Samantha Murphy, “World of Warcraft Predicts Future,” New Scientist (March 2010).

See →. I owe this reference to Anna Wheeler.

See Lesley Sharp, Bodies, Commodities and Biotechnologies (New York: Columbia University Press, 2007).

Ibid.

See Madoff, Immortality and the Law.

CyBeRev used to be open to anyone, but now your have to be approved to participate. See →.

See Benjamin P. Best, “Scientific Justification of Cryonics Practice,” Rejuvenation Research Vol. 11, No. 2 (2008).

See M. Farstada et. al., “Rewarming From Accidental Hypothermia by Extracorporeal Circulation: A Retrospective Study,” European Journal of Cardiothoracic Surgery 20 (2001): 58–64; and B.H. Walpoth et. al., “Outcome Of Survivors Of Accidental Deep Hypothermia and Circulatory Arrest Treated with Extracorporeal Blood Warming,” The New England Journal Of Medicine Vol. 337, No. 21 (1997): 1500–5.

Category

Subject

This paper is based on a talk delivered at the 2012 CAA meeting in Los Angeles, on the panel “Live Forever: Currency and Posterity of Performance Art,” organized by Sandra Skurvida and Jovana Stokic. My thanks go to Sandra Skurvida for inviting me to the panel and commenting on the paper. I also want to thank the students in my seminar “Post-Secular Aesthetics?” for helping me to push some of these ideas further.