A narrative, it seemed to me, would be less useful than an idea.

—Susan Sontag, AIDS and Its Metaphors

I want to talk about what happened to us: to a very specific “us,” and some very strange happenings. I want to tell a story, to give a history to things oblivious to history. What I’m after is a queer problem and it won’t stop moving. I like how they say, you’re just going through a phase. That’s what’s happening to us, we’re going through phases. But a phase isn’t a thing, it’s a word that comes from a way of talking about how things appear. (Originally, the moon.)

1. Ruptures

The Stonewall riots inaugurated the delayed adolescence of queer sex: a catching up on acting out. Empowered by an unprecedented sense of public agency and private experimentation, gay men established commercial sex spaces to foster an ethos of multi-partner promiscuity. Sous les paves, la plage was rewritten for Greenwich Village: beneath the stones, the sling. Fucking was happening on a wholly new scale and in new ways, as pleasures were reconceptualized to serve novel purposes. “By a curiously naïve calculus,” wrote one memoirist of the era, “it seemed to follow that more sex was more liberating.”1

Something else was liberated in this upheaval, another kind of body with its own modes of experimentation: a strange bundle of molecules so elemental in composition and capable of such limited action that it confounds the very definition of what constitutes a life-form. If biologists have reached no consensus on the question of whether viruses should be classified as living organisms or not, epidemiologists, on the other hand, have clarified the conditions that enabled the long dormant and ecologically circumscribed human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) to proliferate along the circuits of desire forged by an accelerating sexual culture.

First diagnosed as a disease afflicting North American gay male communities, AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome) was initially called GRID (gay-related immune disorder), and immediately marked as a specific problem of these communities. This association, despite its persistence to this day, was revealed as a historical contingency unmoored from a true viral genealogy. The emergence of HIV is now traced back to the late nineteenth century, sparked by the political and ecological upheavals of European colonialism in equatorial Africa.2

Things and migrations: The geopolitics of AIDS are inextricable from the nature of its material operations. Unlike an outbreak of Ebola, which swiftly erupts as a legible, and thus containable, terror, HIV operates on principles of patience and stealth. On average, ten years elapse from infection to symptoms. The initial burst of viral reproduction, when bodies are at their infectious peak, go unregistered by standard tests. AIDS, as Susan Sontag noted, is a temporal disease, and thinking in terms of “stages” has been essential to its discourse. The circuitous route by which the landscape of HIV/AIDS has been mapped onto history is predicated on the elusive temporality of the virus itself.

2. Status

How many of us will be alive for Stonewall 35?

—ACT UP poster

That AIDS was immediately confronted as a postmodern phenomenon par excellence and only later addressed as a postcolonial complex is a testament to the vehemence—and context—of the critique that rose to challenge it. Aids Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) exemplifies a second phase in queer sexuality, in which the revelation of a catastrophic co-becoming with inhuman forces was met by new concepts of being and new forms of being together. Under the sign of Saint Foucault, these techniques of the self were produced with, and through, an urgent task of making-visible in the domains of discourse and politics, art and activism. The AIDS crisis, as many have noted, is a crisis of representation.

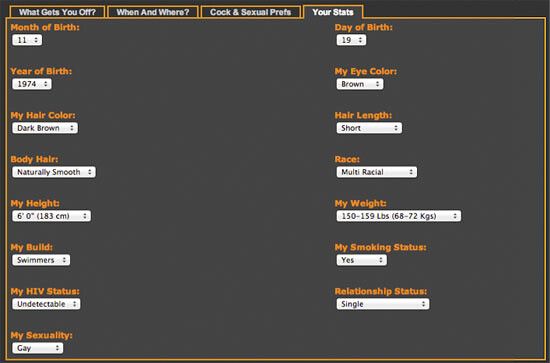

Resolving the question of what HIV/AIDS is has always been tangled up in the problem of whom it affects. The development of an antibody test for HIV in 1985 inscribed a new form of identification: the categories of “positive” and “negative.” In the vernacular of sexually transmitted diseases, one may be said to “have” herpes or hepatitis, but it is only with HIV that the presence or absence of a virus so forcefully marks one as a specific type of being. “What’s your status?” is, from a semantically neutral perspective, a question so open-ended as to be meaningless. Yet when asked by one gay man to another, signification collapses to a strict binary. This positive/negative dyad immanent to gay male culture is subsumed, in turn, by a further division whereby populations marked by the HIV dichotomy are isolated as members of a “risk group” in relation to a naturalized “general population.”

Reflecting on this politicization of HIV/AIDS discourse in the early years of the epidemic, Susan Sontag noted that an AIDS diagnosis exposes an identity that might otherwise have remained hidden: to detect, etymologically, is related to uncovering. This uncovering of identity effects its confirmation and, “among the risk group in the United States most severely affected in the beginning, homosexual men, has been a creator of community as well as an experience that isolates the ill and exposes them to harassment and persecution.”3

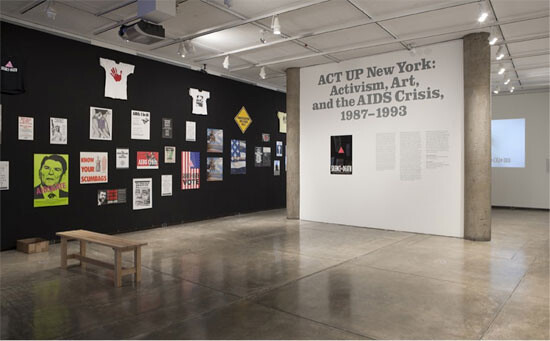

The work and play of this community has been the focus of recent attention in light of the twentieth anniversary of the founding of the ACT UP. The constellation of documentaries, exhibitions, publications, oral histories, and media stories illuminating this terrain bear witness to the enduring vitality of a critical history—while leaving shadowed the complex flows of power that remain undisclosed and unattended to in the ongoing evolution of HIV/AIDS.

3. Undetectable

We are in the midst of constructing a third phase of queer sexuality. The year 1996 saw the advent of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), which enabled a reduction of viral load to levels that elude conventional testing, thus inaugurating a third form of status and a new concept in biopolitics: “undetectable.” To the overdetermined categories of positive and negative has been added an elusive third term belonging to those who are simultaneously both. Signifying a presence that is absent, predicated on suppression and surveillance, the undetectable occupies an indeterminate space and produces new forms of connectivity, at once increasing the capacity of a body and subjecting it to a relentless regime of control. Novel sexual practices have once more emerged, as has an entirely new matrix of representation, connectivity, and sociality. The “end of the AIDS crisis” intersects with the dawn of the internet era.

Each of these three phases is a fiction assembled in retrospect, and their component markers are not so easily fixed as to make an immutable periodization. The libertine sexual ethos of the post-Stonewall era, for example, was not repressed but merely reconfigured during the AIDS crisis. “It is our promiscuity,” Douglas Crimp argued in 1987, “that will save us.”4 Who gets named as “us” here is of course a problem, in the sense that it articulates a particular matrix of seeing and speaking, naming and locating, gathering up and casting away. A history for whom? A story in what language?

It is “we,” the privileged class of the undetectable, who are empowered to speak of a “post-AIDS” culture. It feels rude and arrogant to write such a sentence, but to pretend things are otherwise is something worse, a falsification. I belong to a generation of North American gay men that has never known sexual identity without the specter of HIV infection—and yet for whom AIDS had largely retreated from everyday reality, distanced by media, history, geography. I was six years old when doctors in the United States diagnosed the first case of GRID, and fifteen when I first had sex with a man, a thirty-year-old architect I picked up at my local library where, on the racks of newspapers, one could read of a boy named Ryan White who had acquired HIV through a blood transfusion.

My coming out as gay in the early nineties was attended by a twofold anxiety: the cultural marginalization of sexual difference, and the coding of this difference as death. In 1996, the year of the HAART breakthrough, I moved to San Francisco with a boyfriend. I remember the spontaneous street party that broke out in the Castro when Clinton was elected president. I remember, that year, seeing men sick from AIDS, hollow eyed and skeletal, walking with the help of friends or lovers. Condoms were everywhere, buckets of them for the taking. When I moved to New York in 1999, I vividly remember the surprise (and slight annoyance) at having to actually buy condoms, no longer a ubiquitous freebie. By then, it had been a long time since I saw people visibly afflicted with AIDS in public.

There was no halcyon “before” of unprotected sex for my generation. We have inherited an official safer sex discourse with little but condemnation for sexual contact unmediated by prophylaxis, and a cultural ethos that sanctions unprotected sex principally as something “earned” in the context of a committed relationship subject to rigorous testing—of boundaries and trust no less than antibodies. Sex has always entailed risk, but the quantitative increase of sexual risk under HIV/AIDS has led to a qualitative difference in the formation of sexuality. As Eric Rofes has written of the “post-AIDS” generation:

They have had to contend with profound linkages between gay sex and disease. The primary language about sex that has been placed in their mouths and wired into their brains has a vocabulary of “risk,” “condoms,” and “safer sex.” Instead of living through the period of gay liberation and sexual freedom, then having a house fall on them, they’ve constructed their sexual identities and networks amidst the reality of a rapacious, sexually transmitted virus.5

The concept of a “post-AIDS” generation thus signifies a curious double inheritance: those for whom sexuality is inextricable from HIV and for whom, at the same time, AIDS no longer exists as an immediate reality. I know many people with HIV, but no one with AIDS. The privilege of this situation will seem incomprehensible, if not obscene, to the global millions without access to treatment for HIV infection. If the concept of the undetectable signifies one set of conditions for those coming to terms with successful treatment of HIV (displacing, perhaps, the positive/negative binary with the more urgent categories of insured/uninsured), it mobilizes an entirely different assemblage of problematics at the global level.

A scandal of racism and inequality, at once an instrument and a pathology of neoliberalism, the AIDS crisis is not merely “not over”—it persists as an overwhelming malignancy. The very language of crisis seems to index a spiraling perpetuity: krisis from κρίσις, “the turning point in a disease.” AIDS has not stopped killing. HIV has not stopped spreading. And yet, as Rofes asserts, AIDS as “we” knew it is over. “How can some of us have this feeling that AIDS is over when we have the knowledge that it is not? How can two such different understandings of what is happening around us coexist?”6

Undetectability is founded on this queer coexistence, a constitutive indeterminacy. The virus, if no longer the catalyst for a lethal syndrome, was and remains a central problem of the gay male body. It inhabits both the infected as reality and the uninfected as potential. Drugs have curtailed its lethality but not its ubiquity, and the long-term effects of combination therapies, which continue to evolve, are an open question. We know that AIDS is not what it was, but we’re not at all sure what it has become.

4. Unnatural Participations

An entire sub-race was born, different—despite certain kinship ties—from the libertines of the past.

—Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality: An Introduction

Representation thus remains very much at stake—and contested—in the undetectable era. Its terms have shifted in strange, often counterintuitive ways. One of the seminal texts of undetectability, Tim Dean’s Unlimited Intimacy, argues for the radical potential of bareback subculture. Organized as a self-conscious practice in the late nineties, barebacking—the deliberate abandonment of condoms for anal sex—not only acknowledges but affirms viral transmission. Claiming its own distinct language and rituals, fantasies and communities, codes and representations, barebacking, in Dean’s provocative analysis, is neither a denial nor rejection of the survival techniques developed in response to AIDS, but their very elaboration into “the next logical step in the enterprise of gay promiscuity.”7

Dean’s critique of bareback pornography—an industry outlaw when his book was published, by now ubiquitous and thoroughly assimilated into mainstream porn production—addresses the problem of “what happens when the attempt to represent non-normative sex comes up against norms of representation.”

The fact that HIV, like all viruses, remains invisible to the naked eye poses a challenge to which bareback porn may be regarded as a response. Confronted with an invisible agent that nevertheless is known to be transmitted sexually, the pornographic principle of maximum visibility must generate strategies for making appear on screen something that cannot be seen.8

One such strategy unique to the genre is the use of subtitles. The desired object, the making-visible of a “breeding” inside the body, is rendered as text. Dean cites a scene from Plantin’ Seed, an early film from the notorious (and wildly popular) bareback porn company Treasure Island Media. The subtitle, a technology of translation, is here deployed to transpose the physical fact, sensation, and fantasy of internal ejaculation into the domain of language:

The audience sees subtitles rather than semen; testimony substitutes for visible evidence. We could say that, instead of the image of whitish fluid suddenly coming out of a penis, viewers are given, in white lettering at the bottom of the screen, a representation of something suddenly coming out of someone’s mouth.9

Someone or something: Plantin’ Seed is an image producing its own utterance. As a form of representation grappling with the limits of representation, bareback porn is, Dean argues, a form of thinking, a mode of embodied thought. If, despite the mainstreaming of condomless pornography, the highly self-conscious subculture of barebacking as reflected in the videos of Treasure Island Media represents a minority practice, it is precisely this anomalous position, this bordering, that bestows conceptual force.

Leo Bersani has written of the startling ways in which barebacking may be thought of as a “social practice that, perhaps unprecedentedly, actualizes, in the most literal fashion, psychoanalytic inferences about the unconscious.”10 Unsurprisingly, a psychoanalytic critique of barebacking sees only death (drive). “Nothing can come from this practice,” Bersani declares:

Power has played no tricks on the barebacker: from the beginning he was promised nothing more, and has received nothing more, than the privilege of being a living tomb, the repository of what may kill him, of what may kill those who have penetrated him during the gang-bang, of what has already killed those who infected the men who have just infected him.11

What Bersani elides in his account of barebacking as an “ego-divesting discipline” is the fact that barebackers have been promised something more: a reprieve from the automatic death sentence of HIV. Bersani writes as if the antiretroviral revolution never took place. Dean rightly cautions that barebacking is an overdetermined phenomenon that cannot be said to depend on the advent of HAART. At the same time, he notes that the greatly expanded lifespan of HIV carriers is inextricable from the development of bareback culture. Where Dean strategically underplays the role of HAART in barebacking to consider the larger context of its practice, Bersani ignores it altogether. As such, his characterization of barebacking as death-driven strikes me as a totalizing and misguided imposition of his theoretical biases on both the empirical reality and motivating fantasies of barebacking, an image of thought unsuited to the krisis of undetectability.

“We are in a time of relational crisis,” writes Bersani, “of a dangerous but also potentially beneficial confusion about modes of connectedness, about the ways in which who or what or how we are depend on how we connect … If there is no moment at which human connectedness has not already been initiated, we might nonetheless posit, largely for heuristic purposes, different plateaux of relationality.”12

The difference, perhaps, of A Thousand Plateaus? For Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, every claim for “what we are,” any discourse on the nature of being, is systematically overthrown in favor of an ontology, an ethics, and a practice of becoming. An experiment in how to do things with viruses, a production of the body as desubjectivized multiplicity, barebacking is, in the terminology of Deleuze and Guattari, pack practice par excellence: a becoming-animal of the “pig.”

In the vernacular of barebacking, Dean explains, “men are pigs and wolves and horny toads, gaily cavorting, feeding and breeding.”

[Wolf] is an outmoded term for male sexual aggressor … whereas pig is a term of more recent derivation that designates a gay man whose motto is “No Limits!” … Or perhaps wolves metamorphosed into pigs. A term of approbation in bareback subculture, pig refers to a man who wants as much sex as he can get with as many different men as possible, often in the form of group sex.13

It’s tempting (if only for heuristic purposes) to read this metamorphosis of wolves into pigs alongside the critique of Freud developed by Deleuze and Guattari. Becoming-animal is their corrective, in part, to Freud’s interpretive reduction of a wolf pack in one of his patient’s dreams to a single, Oedipal wolf.14 And yet the most articulate and dedicated of bareback polemicists would go even further, conceptualizing their pack practice as the vanishing point of a becoming-imperceptible.15 Treasure Island Media founder Paul Morris has framed the “irresponsibility” of barebacking as a willful devotion to a transindividual ethos “with little regard for anything else, including life itself.”

The everyday identity evanesces and the individual becomes an agent through which a darker and more fragile tradition is enabled to continue. Irresponsibility to the everyday persona and to the general culture is necessary for allegiance to the sexual subculture, and this allegiance takes the gay male directly to the hot and central point where what is at stake isn’t the survival of the individual, but the survival of practices and patterns which are the discoveries and properties of the subculture.16

To align oneself with “practices and patterns” in opposition to subjecthood accords precisely with Nietzsche’s famous proposition that “there is no ‘being’ behind doing, effecting, becoming; the ‘doer’ is merely the fiction added to the deed.”17 This is not to claim that every bareback power bottom is some kind of jizz-drenched Übermensch, nor that the neo-Nietzschean “death of the subject” proclaimed by the poststructuralists has found its kinky apotheosis. The practices and patterns of bareback subculture arise from specific cultural and political contexts, and they have real consequences.

In her powerful, cautious essay on “The Ethics of Becoming-Imperceptible,” Rosi Braidotti affirms such radically transformative projects of disappearance. We yearn, she says, to dissolve into a flow of inhuman becomings—with all the joy and pain this entails, and despite having lost so many to “dead-end experimentations of the existential, political, sexual, narcotic or technological kind.”18 If barebacking has emerged as a problem and a paradigm of the undetectable, we are only just beginning to find ways to discuss such strange happenings. “Becoming-imperceptible is the event for which there is no immediate representation.”19

×

Thanks to Johanna Burton, Christoph Cox, and Douglas Crimp.

Michael Callen, Surviving AIDS (New York: HarperCollins, 1990), 4.

See most recently Craig Timberg and Daniel Halperin,Tinderbox: How the West Sparked the AIDS Epidemic and How the World Can Finally Overcome It (New York: The Penguin Press, 2012).

Susan Sontag, AIDS and Its Metaphors (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1989).

Douglas Crimp, “How to Have Promiscuity in an Epidemic,” in AIDS: Cultural Analysis/Cultural Activism, ed. Douglas Crimp (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1988), 253.

Eric Rofes, Dry Bones Breathe: Gay Men Creating Post-AIDS Identities and Cultures (New York: Haworth Press, 1998), 8.

Ibid., 10.

Tim Dean, Unlimited Intimacy: Reflections on Bareback Subculture (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009).

Ibid., 112.

Ibid., 134.

Leo Bersani and Adam Phillips, Intimacies (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010), 43.

Ibid., 50.

Leo Bersani, Is the Rectum a Grave? And Other Essays (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012), 87.

Unlimited Intimacy, 49.

See Deleuze and Guattari, “One or Several Wolves?” in A Thousand Plateaus, trans. Brian Massumi (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), 26–38.

“If becoming-woman is the first quantum, or molecular segment, with the becomings-animal that link up with it coming next, what are they all rushing toward? Without a doubt, toward becoming-imperceptible. The imperceptible is the immanent end of becoming, its cosmic formula.” A Thousand Plateaus, 279.

Paul Morris, “No Limits: Necessary Danger in Male Porn,” paper presented at the World Pornography Conference, Los Angeles, California, August 8, 1998.

Friedrich Nietzsche, On the Genealogy of Morals, trans. Walter Kauffmann and R.J. Hollingdale (New York: Vintage Books, 1989), 45.

Rosi Braidotti, “The Ethics of Becoming-Imperceptible,” in Deleuze and Philosophy, ed. Constantin V. Boundas (Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh Press, 2006), 133.

Ibid., 156.