To Helmut, to whose rage and love the ensuing lucubration is due.

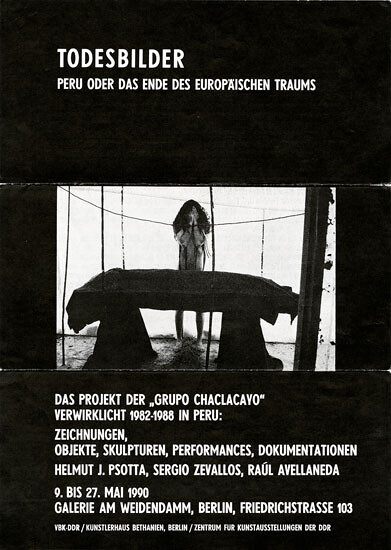

The deeply transgressive sexual dissident work of Grupo Chaclacayo (1983–1994) has remained largely unknown until today.1 Narrated more like a myth or a rumor (almost no one has been able to see their actual works in almost thirty years), this collective endeavor was one of the most daring episodes of artistic experimentation and sexual-political performance to emerge in Peru during the 1980s. These experiments were carried out amidst a violent armed conflict between communist subversive groups and the Peruvian government. Grupo Chaclacayo consisted of three artists (the German Helmut Psotta and his Peruvian students Sergio Zevallos and Raul Avellaneda), who, from 1982 to early 1989, voluntarily sequestered themselves in a house on the outskirts of Lima. In 1989 they were forced to move to Germany by the lack of economic resources in Peru and by the social and political hostility resulting from a war that would leave a death toll of seventy thousand people in nearly two decades (1980–2000).2 After arriving in Germany a few months before the fall of the Berlin Wall, Grupo Chaclacayo organized an exhibition summing up their work in Peru and including new installations and performances. The exhibition was entitled “Todesbilder. Peru oder Das Ende des europäischen Traums” [Images of Death: Peru or the End of the European Dream] and was shown in cities such as Stuttgart, Bochum, Karlsruhe, and Berlin, among others.3 The group disbanded around 1995. The works and materials they produced never returned to Peru.

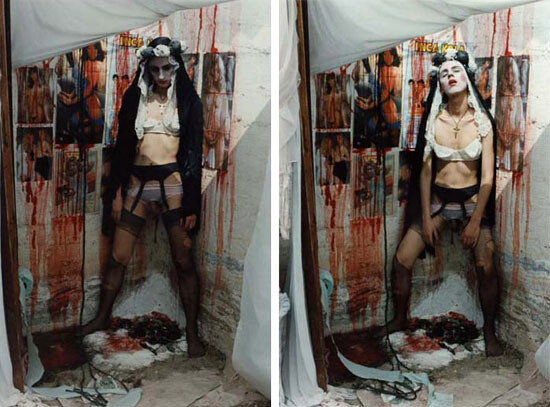

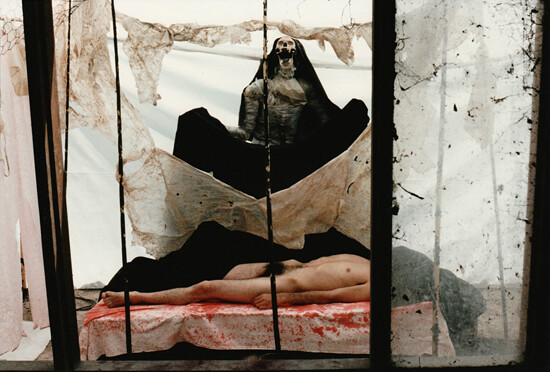

The group’s extensive work is an explosive reworking of the surplus materials of urban modernity (such as city waste and detritus), merging representations of mystical pain and religious martyrdom with thousands of images of tortured and mangled bodies. The terror, incomprehension, and fascination their experiments provoked was the result of the darkness of their work: cheap, anti-glamorous stagings that alluded to ideological dogmatism and sickness; homoerotic representations between abjection and necrophilia; transvestite recodings of mystical pain; the use of coffins and bodily remains, excretions, and fluids; and references to fetuses, corpses, and mutilated and crippled bodies. Far from being an orthodox claim to a homosexual sensibility, their work was an experiment in the production of abnormal and deviant subjectivities that undid gender and social identities, using a sadomasochistic and ritual vocabulary to exorcise the oppressive effects of ideology, religion, and the legacy of colonialism.

It is no coincidence that the emergence of Grupo Chaclacayo paralleled the appearance of an unprecedented countercultural and alternative cultural scene in Lima between 1982 and the early 1990s, known as the “subte” [underground] movement. These disruptive practices took the form of collective experiences at the intersection of rock and punk, ephemeral and precarious self-constructed architecture, DIY fanzines, anarchist movements, junk aesthetics, scum poetry, and shock theatre. A characteristic of these new radical groupings was the refusal to be silent in the face of the torture and disappearances that were part of the “dirty war” that the Peruvian state conducted against many sectors of the civil population as a response to subversive activities and attacks by Shining Path.4 Rock groups such as Leuzemia [a changed spelling of “Leukemia”], Narcosis, Zcuela Cerrada [a changed spelling of “Closed School”], Guerrilla Urbana [Urban Guerilla] and Autopsia [Autopsy], as well as album covers, agit-prop flyers, and collages produced by artists such as Herbert Rodríguez, Jaime Higa, and Taller NN, testify to the willingness of anarcho-punk artists to confront the dire situation in Peru.5

This radical moment in music was similar to one that took place in architecture, with the anarchist, ephemeral public interventions by a collective called Los Bestias (1984–1987), or in poetry, with the ephemeral “commune” founded by Movimiento Kloaka (1982–1984), which used literary production as a space of social struggle. The rebellious attitudes of these freaks, queers, misfits, drunks, and malcontents caused some friction with Shining Path and orthodox communist discourses, but also with traditional socialist parties, including the spokespeople and critics of the new cultural Left, who saw in these scandalous activities the signs of social disintegration instead of the yearned-for socialist unity. These new subcultural groupings demanded a distinct form of identification and collective communication through their socially marginalized bodies, which had no place in traditional society.6 The reactions to Grupo Chaclacayo illustrated the hostility and revulsion that attended the rise of Lima’s underground movement.

It is revealing that some of the initial reactions to the work of Grupo Chaclacayo used the conservative discourses of art to condemn and pathologize these operations of gender disobedience. After their first and only exhibition in Peru, which took place at the Lima Art Museum in November 1984 and was entitled “Perú, un sueño…” [Peru, a dream…], a local art critic denounced the alleged excesses and political incorrectness of the group’s work. Invoking orthodox notions of artistic quality and moralist ideas, the critic Luis Lama described the group’s photographs, installations, and collages as a “null pseudo-artistic misrepresentation,” an “allegory of decadence,” “paraphernalia of blasphemy,” a “vivisection of degeneration,” a “homosexual myth,” and an “excessive search for pathos.” He excluded the work from serious artistic discussion and instead addressed it clinically, calling the group’s images “psychopathological…perversions that are closer to Lacan than to Marx.”7 The outrage aroused in the art critic was a sign of the danger these queer grammars posed—and still pose—to the heteronormative social and cultural order. His horror seemed amplified by the place these deviant practices occupied: a museum then supposedly reserved for the modern art of the elite—preferably male, white, straight, clean, and disciplined.

Where to situate the overlooked practices of sexual disobedience, sadomasochistic actions, and “crip” representations of Grupo Chaclacayo?8 How to intervene in the rhetorics employed by artistic discourses to differentiate the moralizing and “correct” aesthetic of the heterosexual body from others marked by disability, deviance, and abjection? Is it possible to recover these episodes of subaltern visibility and sexual disobedience for art history without turning them into mere exotic figures or footnotes in dominant narratives? What political strategies do theatricality, ridicule, and sickness offer for imagining micro-histories that shatter the privileged space of heterosexual subjectivity?

“I am the bride of Christ”

Grupo Chaclacayo’s self-imposed exile in 1982 began with the departure of the German artist Helmut Psotta from the art school at the Pontifical Catholic University in Lima, where he had been a visiting professor.9 While he was teaching at the art school Psotta organized workshops that directly addressed the growing violence of the internal armed conflict, nurturing a profoundly visceral and bodily artistic practice that contested the academic and religious norms of the university. It is for these activities that Psotta was removed from the university after only a few months of teaching. This is when Zevallos and Avellaneda decided to drop out of art school and work with him. The move to a vacant house on the outskirts of Lima, initiated by Psotta, was an attempt to gain some distance from homophobic, conservative local mores, but also from the art system, its economic circuits, and its models of good taste and social validation—models in which the group’s own practices would find no place. Through actions and images produced in that house, and occasional forays into public space (cemeteries, schools, beaches, and old abandoned houses), the group gave birth to an unusually profane sexual iconography that stood somewhere between a sexual-political dramatization of Catholic devotion and a queer resignification of a sinister landscape where tortured and murdered bodies were discovered on a daily basis.

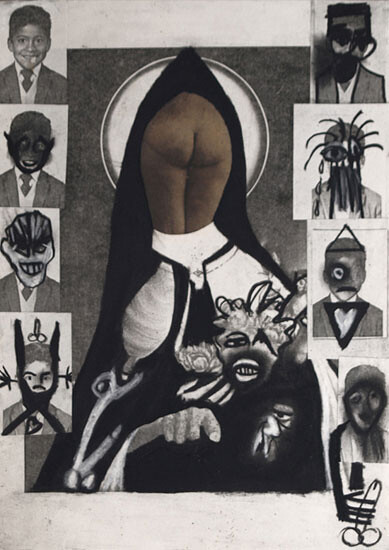

One of the first actions of Grupo Chaclacayo, even before it was constituted as a collective, was a procession with a small altar made of garbage, done by Zevallos while still attending art school in 1982. The poorly-made sculpture was inappropriate for the modernist aesthetic values of the academy, but even more threatening was the act of taking it into public space on a pilgrimage that parodied a massive Catholic rite. These first exercises were a prelude to the group’s characteristic artistic production: elaborate representations of abnormal corporalities and desires. From then on, their work would acquire a strongly theatrical component, as well as a sarcastic transvestitism that used symbols associated with fanaticism and religion to, for example, transform papal miters into Ku Klux Klan hoods or Christian crosses into Nazi swastikas—linking unacknowledged relatives within the same totalitarian genealogy. Many of these mise-en-scènes mixed elements taken from altars, religious prints, popular graphics, pornographic magazines, children’s drawings, photographs from family albums, coffins, and press clippings, allegorizing not just the obscene covert criminality of the confrontation between government and insurgent groups, but also staging the death sentence of deviant and sexually dissident bodies within a highly repressive heteronormative regime. These sexually dissident bodies were especially vulnerable in a time where the HIV/AIDS crisis was driving new forms of legal and institutional control over the body and sexuality through normalizing and moralizing rhetoric, which would expand internationally throughout the decade.

Once formed as a group and established on the outskirts of Lima, Grupo Chaclacayo’s first (and most powerful) performances, directed by Psotta, were held at the shore of the Pacific Ocean, involved many collaborators, and were documented by photographer Piero Pereira. In Pereira’s series of photographs entitled La agonía de un mito maligno [The agony of an evil myth] (1984), various naked people appear half-covered with robes and hoods in a sort of obscure oceanfront wake or ritual sacrifice. These sinister figures stand in front of bodies that are half-buried in the sand. In other images from the series, these fake celebrants hold a vigil for the dead bodies. The furtive and intimidating ceremony evokes religious symbols, but also the symbols of right-wing extremist organizations. Other images from the series show a cross-dressed figure, in the guise of Saint Rose of Lima (the first Saint of the Americas), traversing a desert dotted with black flags and crosses, and finally collapsing in agony.

The image of Saint Rose (1586–1617), venerated for her spiritual devotion and her self-inflicted corporeal punishment, was a persistent symbol in the actions, paintings, and drawings produced by Grupo Chaclacayo. Saint Rose is revealed by the group as an ambiguous symbol of how pain and extreme suffering are associated with the promises of redemption propagated by the discourses of religion and the state, highlighting the role of religious imaginaries in the histories of Western oppression.10 “That which used to happen through the Church now happens through the banks and the politicians,” said Psotta in 1990, alluding to the hidden alliances between Christianity and the exploitation and violence that maintain a moral and economic order in which the sacred is always a fetish or a commodity.11

Other appropriations of the portrait of Saint Rose can be found in the series of drawings Rosa Paraphrasen (ca. 1985–1986) by Helmut Psotta and in the early series of collages Estampas (1982) by Sergio Zevallos. In the latter series, the body of Saint Rose, the so-called “bride of Christ,” appears deformed, cross-dressed, and violated by a cohort of malformed angels and seraphim. Saint Rose also appears as part of a pagan sex orgy, emphasizing the incestuous and erotic matrix behind religious mandates. In other actions carried out as a response to some of the most violent crimes of those years, the painful punishment of Saint Rose’s body echoes the government’s politics of extermination masked by religious devotion.

In the series of photographs Rosa Cordis (1986), made by Sergio Zevallos in collaboration with the poet Frido Martin, a character in drag with a black tunic and a crown of roses (an allusion to Saint Rose) applies make-up, then masturbates next to what seems to be a dead body in a cubicle that is dyed red and covered with Playboy clippings. In the following image, the saint changes into a hooded figure and sodomizes the cadaver.12 Rosa Cordis was a reaction to governmental actions such as the bestowal of the prestigious Order of the Sun medal on Saint Rose for the four-hundredth anniversary of her birth, just a few weeks before the vicious “slaughter of the prisons,” and a few months after the extrajudicial executions in Lurigancho prison.13

The vanity and arrogance of authoritarian discourse are also represented through parodic “documentary” works, such as Retrato de un general peruano [Portrait of a Peruvian General] (1987) by Raul Avellaneda. This work consisted of a portrait painting and various look-alike drawings and photographs of a seventy-year-old general who was the husband of the owner of the house the group rented, and who declared himself a follower of the Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet. The group also confronted authoritarian discourse through collective actions for the camera that denounced the perverse complicity between some local conservative bishops and the military forces that clandestinely tortured and murdered indigenous and peasant communities.

Grupo Chaclacayo staged some of these actions in the context of the celebrated first visit of Pope John Paul II in 1985, when he stopped in several Peruvian cities and provinces (such as Lima, Arequipa, and Ayacucho, a city devastated by the war). The Pope’s visit was a very important media event, addressed by the group through homoerotic photographs in which a figure of the Holy Father, half naked, half covered in white robes, lustfully runs his red-dyed hands over what looks like a mixed-race dead body.14

Grupo Chaclacayo was very aware of the complicity of right-wing religious authorities in the “dirty war” waged by South American dictatorships against leftist opponents during the 1970s and ‘80s. In those years, conservative Church hierarchies not only turned a blind eye to the torture and disappearances committed by the anti-communist authorities, but in many cases colluded with them to persecute priests and Church workers who took a stand against human rights abuses. Conservative Church authorities also sought to condemn progressive ideas such as those of the Liberation Theology movement, which embraced a critique of unjust economic and social conditions and proposed a reading of Catholic faith through the eyes of the oppressed and the poor, which detractors described as “Christianized Marxism.”15

The Soldier and the Priest, the Child and the Corpse

The actions and representations of Grupo Chaclacayo on the subject of queer religiosity can also be understood as an attempt to revive the stories of androgynous devotion and transvestite rituals that have been constantly suppressed throughout history. The use of Catholic imagery by the group exalts the cheap forms of visual representation of Andean Virgins and local saints, establishing operations of self-identification with popular and lumpen culture (everything considered poor and vulgar from the urban, upper-class perspective), which the group interspersed with images of prosthetic limbs, crosses, portraits of children, blood, mangled bodies, gunpowder, and semen, proposing a renewed space of political antagonism. The images are a staging similar to what queer theorist Beatriz Preciado has described as the “unspeakable attraction between the soldier and the queer, between the dyke and the queen, between the cop and the whore, between the artist and the illiterate, between the aesthetic of the martyrs and sadomasochistic sexual culture.”16

These queer forms of theatricalizing power and of resignifying religious morality can be related to a wide repertoire of Latin American sexual disobediences and pagan feasts, which have rarely been shown and discussed. For instance, the drawings of phallus-altars for the Virgin of Guadalupe by the Mexican feminist Mónica Mayer in the late 1970s; the feminist religious posters and stickers printed with prayers for abortion rights and freely distributed by the Argentine collective Mujeres Públicas [Public Women]; the liturgical experiences and subversive actions of the Chilean duo Yeguas de Apocalípsis [Mares of the Apocalypse] during Pinochet’s dictatorship; the performances, graffiti, protests, and street theater by the Bolivian anticapitalist anarcho-feminist collective Mujeres Creando [Women Creating] in open confrontation with hegemonic political and religious systems of power since the early 1990s; the recent street pilgrimages of Chile’s first trans saint, Karol Romanoff, organized by the Coordinadora Universitaria de Disidencia Sexual [University Coordinator of Sexual Dissidence] (CUDS); and the surreptitious public appearances of Peruvian drag queen Giuseppe Campuzano as an Andean Virgin. These deviant performances undo devout models of femininity (the mother, the Virgin, the wife, the blessed), but also undermine the strong component of morality that organizes behavior in public space. National ideologies, traditional family values, and Catholic devotion are part of a strong conservative social matrix in South America. Abnormal sexual-political practices confront and subvert this matrix by intervening in the codes that divide the social body into normal subjects and sick subjects, into proper sexualities and wrong sexualities, into people who deserve to live and people who deserve to die.

It is the denunciation of heteronormative protocols and the pathologization of queer and disabled bodies (subjects with either mental or physical impairments that make it difficult for them to meet the productive demands of capitalism) which have recently given rise to a collective platform for resistance and for enacting new political communities. The stance against concepts of normalcy (corporeal, sexual, social, and mental) taken by both queer bodies and crip bodies does not advocate for inclusion into majority values, but rather for a radical transformation of certain systems of meaning and social structures that label non-normative bodies as “disordered.” The political potential of crip as a means of fighting the hegemony of able-bodied, heterosexual standards lies in its ability to fracture the collective understandings of what is a desirable social body, thereby putting into question the reproductive/sexual and moral well-being of a nation.

In a recent, very moving silent performance entitled Lifeline (2013), Peruvian drag queen Giuseppe Campuzano (who was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis two years ago), in collaboration with Germain Machuca, asserts the experience of the queer and the disabled by showing his own vulnerable, almost motionless body in drag in a wheelchair. Campuzano is pushed along by his friend in a room filled with images and texts of deviant bodies from the pre-Columbian era to the present, which Campuzano collects as part of his project Transvestite Museum of Peru, a queer counter-reading of history.17 As the artist Renate Lorenz has written regarding the queer resignification of pain, the drag “prevents the body perceived as sick from being completely integrated into the discourse on sickness and from eliciting pitying or sentimental reactions.”18 Like the work of Grupo Chaclacayo, the action by Campuzano reclaims the devalued body and returns to the public eye that which had previously been expelled and labeled as abnormal or sick. These representations resignify queer and crip culture in a process through which bodies that had been denied their human status acquire, by other routes, the possibility of being subjects of enunciation, of being political agents of knowledge production.

The crip vocabulary mobilizes the subversive possibilities of disability, pain, and even death. In Grupo Chaclacayo’s work, the presence of prosthetic bodies, skeletons, corpses, and mummies, which are used to stage scenes of annihilation, suggests a different war beyond the Peruvian armed conflict, one both underground and unnoticed: the war declared against effeminate, weird, ugly, monstrous, and sick people. The social pleasure that the death sentence of the homosexual produces, the yearning for the disappearance of gender non-conforming and disabled bodies, emerge in the group’s performances as a way of twisting the prevailing hypotheses about the origins of political violence in Peru. Contrary to these prevailing hypotheses, Grupo Chaclacayo locates one of the origins of this political violence in ideas of able-bodied heteronormativity, which are integral to the maintenance of the nation’s healthy borders and to the accepted war against any subject disobeying the hegemonic regimes of the “normal.”

The reading of these bodies advanced by certain critics, who asserted that these bodies required psychiatric rehabilitation or even incarceration, continued to hound the group’s homoerotic artistic grammar. In a 1989 article, the art critic Luis Lama (who had rebuked their work on moral grounds in 1984) dismissed the group’s work, then exhibited at the Künstlerhaus Bethanien in Berlin, accusing it of being “shrill and frivolous apologies” for Shining Path.19 Beyond the threat that such accusation entailed for artists (at the time, it could mean persecution, kidnapping, torture, or forced disappearance), it is revealing how these anarcho-queer outbreaks were associated with the terror produced by the Shining Path’s armed raids in Peru.

Lama’s denunciation represents a powerful example of how the group’s inappropriate expressions of sexuality were interpreted as a threat to the national body. Equating “terrorists” with “queers,” however subtly, was an example of how this hyper-sexualized theatricality and cripple-homosexual fiction that blended the soldier and the priest, the child and the corpse, could be a metaphor just as explosive and threatening to heteronormative discourses as the murderous Shining Path group.

This research is part of a collective project conducted by Red Conceptualismos del Sur (Southern Conceptualisms Network) about the transformations in ways of understanding and engaging in politics that took place in Latin America in the 1980s. The first phase of this project was recently presented at the exhibition “Losing the Human Form: A Seismic Image of the 1980s in Latin America” at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía Madrid (October 2012–March 2013) and Museo de Arte de Lima (November 2013–February 2014). Part of this research was conducted in collaboration with the Peruvian researcher Emilio Tarazona between 2008 and 2011. Some of these materials will be presented for the first time in Peru at the exhibition “Sergio Zevallos in the Grupo Chaclacayo, 1982–1994,” curated by Miguel A. López at the Museo de Arte de Lima in November 2013.

The armed conflict in Peru ended in 2000 with the fall of the right-wing dictator Alberto Fujimori and his criminal and corrupt government. The principal actors in the war were the Shining Path Maoist organization (founded in a multiple split in the Communist Party of Peru), the “Guevarist” guerrilla group Túpac Amaru Revolutionary Movement (or MRTA), and the government of Peru. All of the armed actors in the war committed systematic human rights violations and killed civilians, making the conflict bloodier than any other war in Peruvian history since the European colonization of the country.

The show toured from 1989 to 1990 at the Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen (ifa) in Stuttgart, the Museum Bochum, the Badischer Kunstverein in Karlsruhe, and at the Künstlerhaus Bethanien in Berlin, among other venues. In addition, the group presented a series of live performances in Maxim Gorki Theater, Berlin, in May 1990. Their last presentation as a group was at Fest III (September 29–October 3, 1994) in Dresden, with the participation of, among others, the Yugoslavian/Slovenian band Laibach, the dance-theater company Betontanc, the filmmaker Lutz Dammbeck, and the artist and theoretician Peter Weibel.

On December 30, 1982, the government of Peru granted broad powers to the armed forces for “counter-subversive” campaigns in the parts of the central Andes deemed to be in a “state of emergency.” The human rights abuses that resulted were part of a deliberate strategy on the part of the military government. See Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación, Informe Final (Lima: CVR, 2003).

For a short history of Lima’s punk scene and “subte” movement, see Shane “Gang” Greene, “Notes on the Peruvian Underground: Part II,” Maximum Rocknroll 356 (January 2013). See also Carlos Torres Rotondo, Se acabó el show. 1985. El estallido del rock subterráneo (Lima: Editorial Mutante, 2012).

For a longer reflection about the radical artistic interventions and the underground scene in Peru in the 1980s, see Miguel A. López, “Discarded Knowledge: Peripheral Bodies and Clandestine Signals in the 1980s War in Peru,” in Ivana Bago, Antonia Majaca, and Vesna Vukovic (eds.), Removed from the Crowd: Unexpected Encounters (Zagreb: BLOK & DeLVe – Institute for Duration, Location and Variables, 2011), 102–41.

Luis Lama, “Pobre Goethe,” Caretas (December 3, 1984): 63.

“Crip” is a play on the word “cripple,” and its use here refers to the political resignification of disability and the questioning of how and why disability is constructed and naturalized. The “cripple” movement reclaims language and self-representation to direct them towards different modes of existence, confronting the dominant ideologies of “normalcy” and its medical lexicon. The movement also aligns itself with other bodies that have been pathologized, such as the homosexual. Crip activism and theory mobilizes the subversive potential of disabled bodies that refuse able-bodied norms, the productive demands of capitalism, and static identities. For the intersections of crip and queer, see Robert McRuer, Crip Theory: Cultural Signs of Queerness and Disability (New York: NYU Press, 2006).

Helmut J. Psotta (1937–2012) was born to a Jewish mother, Rosa Grosz, and a German father who was member of the Nazi Party. Psotta attended the Folkwang School in Essen, but found the school’s ideological tensions unbearable. Soon after he left the school, Psotta worked with metal designer Lili Schultz in her class at the Düsseldorf School of Arts, where Psotta met Joseph Beuys. At the age of twenty-three Psotta visited South America for the first time. He taught at the Institute of Design in the Architecture Department of the Catholic University of Santiago de Chile, and after seven years decided to visit Germany. Shortly thereafter, there was a military coup in Chile and his return to the country was no longer possible. Psotta moved to Gahlen, in Germany, where he created one of his major early series, entitled Pornografie—für Ulrike MM. He gave some lectures and seminars at the Rijksakademie van beeldende kunsten in Amsterdam, at the Jan van Eyck Academy and the Academy of Fine Arts in Maastricht, and at the Design Academy Eindhoven, among other schools. During these years his mother died and he decided to move to Utrecht, where he produced the series Konkrette-Poesie and the cycle of drawings entitled Sodom—für C. de Lautréamont. Despite various offers, he refused to make his work public, as he believed that only through anonymity could he be free as an artist. He eventually received an invitation to teach at the Art School of the Catholic University in Lima, where he lived between 1982 and early 1989.

Helmut Psotta, “Die Koloniale Jesusbraut Rosa von Lima und die Korruption der weißen Kaste order. Eine lyrische Version europäischer Brutalität…,” in Grupo Chaclacayo, Todesbilder. Peru oder Das Ende des europäischen Traums (Berlin: Alexander Verlag, 1989), 39–49. The beatification of Saint Rose of Lima in Rome in 1668, and her canonization by Pope Clement X in 1671, can be interpreted as a strategic gesture by the Church to consolidate its hierarchy and to symbolically proclaim the success of the processes of evangelization in the Americas.

Dorothee Hackenberg, “Dieser Brutälitat der Sanftheit. Interview mit Helmut J. Psotta, Raul Avellaneda, Sergio Zevallos von der Grupo Chaclacayo über ‘Todesbilder,’” TAZ (January 26, 1990), 22. In a 1921 text, Water Benjamin describes capitalism as a “religious phenomenon” whose development was decisively strengthened by Christianity: “Capitalism is purely cultic religion, without dogma. Capitalism itself developed parasitically on Christianity in the West—not in Calvinism alone, but also, as must be shown, in the remaining orthodox Christian movements—in such a way that, in the end, its history is essentially the history of its parasites, of capitalism.” Walter Benjamin, “Capitalism as Religion,” trans. Chad Kautzer, in Eduardo Mendieta (ed.), The Frankfurt School on Religion: Key Writings by the Major Thinkers (London: Routledge, 2005), 260.

For these images, the poet Frido Martin (Marco Antonio Young) performed as a queer Santa Rosa. Martin was one of driving forces behind the radical Peruvian poetry of the early 1980s, appearing with the Movimiento Kloaka and with the rock group Durazno Sangrando (consisting of Fernando Bryce and Rodrigo Quijano) in several public performances and poetry readings.

The “slaughter of the prisons” refers to the political repression that took place on June 18 and 19, 1986, following a riot by prisoners accused of terrorism in various prisons in Lima. The riot was started with the intent of capturing foreign media attention before the 18th Congress of the International Socialist (June 20–23, 1986), which was organized for the first time in Latin America. This slaughter was the greatest mass murder of the decade.

The speech of John Paul II in Ayacucho was delivered in the city airport, in February 1985, right next to Los Cabitos army headquarters, where a large number of peasants were brutalized and punished under suspicion of being “terrorists.” The inhabitants of Ayacucho had been denouncing these crimes since 1983, but they were ignored by the conservative archbishop Federico Richter Prada and by other local religious authorities who collaborated in the preparation of the papal speech. The Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (CVR) confirmed in 2003 that at least one hundred people were killed and illegally buried in Los Cabitos in those years. For a moving testimony by a Jesuit priest who confronted the subversive groups, military abuse, and right-wing religious authorities in Ayacucho during 1988 and 1991, see Carlos Flores Lizana, Diario de vida y muerte: Memorias para recuperar la humanidad (Cusco: Centro de Estudios Regionales Andinos Bartolomé de las Casas, 2004).

One of the founders of Liberation Theology was Peruvian theologian Gustavo Gutiérrez Merino, who coined the term “liberation theology” in 1971 and wrote the first book about this theological-political movement in 1973. See Gustavo Gutiérrez, A Theology of Liberation: History, Politics and Salvation (New York: Orbis Books, 1988).

Beatriz Preciado, “The Ocaña we deserve: Campceptualism, subordination and performative policies,” in Ocaña: 1973–1983: acciones, actuaciones, activismo (Barcelona: Institut de Cultura de l’Ajuntament de Barcelona, 2011), 421.

Action performed at the Sala Luis Miró Quesada Garland, in Lima, as part of the project eX²periencia curated by Jorge Villacorta in February 2013. For a broader consideration of Transvestite Museum of Peru see Giuseppe Campuzano, Museo Travesti del Perú (Lima: Institute of Development Studies, 2008); and Miguel A. López, “Reality can suck my dick, darling: The Museo Travesti del Perú and the histories we deserve,” Visible Workbook 2 (Graz: Kunsthaus Graz, 2013).

Renate Lorenz, Queer Art: A Freak Theory (Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, 2012), 81.

Luis Lama, “Perversión y Complacencia,” Caretas (November 20, 1989): 74–76.

Category

A preliminary version of this text was presented at the panel “Latin American Art as the Programmatic of the Political: The New Constructed Canon?” chaired by Claudia Calirman and Gabriela Rangel, during the XXX International Congress of the Latin America Studies Association (May 23–26, 2012) in San Francisco, California, and at the seminar “Campceptualisms of the South: Tropicamp, Performative Politics and Subalternity” organized by Beatriz Preciado at the Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona - MACBA (November, 19–20, 2012).