At a recent symposium on art and gender politics convened by Carlos Motta at the Tate Modern in February 2013, a series of short manifestos delivered by artists, activists, and scholars had the peculiar effect of casting feminism as part of an anachronistic and naive version of contemporary politics.1 At the symposium, Beatriz Preciado, author of Testo Junkie, rejected the idea of a feminism still organized around male and female forms of embodiment and went on to outline a vision of a new regime of power that had little use for conventional gender demarcations. Outlining the “pharmacopornographic” regimes that regulate the body politic, Preciado gave a dazzling overview of a form of the medico/pharmaceutical management of life. She outlined a bleak vision of death and health that involved a kind of totalized pharmaceutical control of pleasure and pain through the production of new forms of prosthetic subjectivity.2

At the conference I delivered an elaboration on my “Gaga manifesto” and unfolded another project on anarchy and transformative politics.3 At least one participant characterized this as an uncritical celebration of mainstream culture lacking an awareness of the serious and often deadly mechanics of global capitalism. Despite the way that feminism was cast as anachronistic at the conference, Preciado and I, in some ways, were saying similar things in very different theoretical lexicons about the end of social norms, the decaying structures of binary gender, and the technological reinvention of sexuality, gender, and reproduction. While Preciado calls her model of a global rule “sex-capitalism” or “punk capitalism” within a pharmacopornographic regime,4 I seek openings in this new regime for different formulations of kinship, pleasure, and power. I call these “Gaga Feminism.”

Theories of capitalism, unlike theories of feminism, it seems, never go out of style, especially theories of a protean capitalism that evolves as it grows, learning quickly and seemingly intuitively how to exploit every minute shift and change in human behavior. Preciado’s theories of capitalism in Testo Junky are compelling, fast-paced, and laced with speedy testosterone-induced insights that would not be out of place in a William Burroughs novel. “The truth about sex,” writes a blissed out Preciado channeling Foucault, “is not a disclosure; it is a sexdesign.”5 But feminism also lurks in the corners of Preciado’s book, occasionally as a superego chastising her for abandoning pure womanhood, sometimes as a poststructuralist peek at what we might call, to misquote The Invisible Committee’s The Coming Insurrection, the coming exploitation; and at other times, Preciado calls upon a new feminism, with a new grammar of gender, to “turn pharmacopornographic hegemony upside down.”6

In response to Preciado and in solidarity with this new feminist project that she gestures towards, I propose that even as capitalism shifts course, changes its emphasis, and reorganizes exploitation and currency, feminism and other forms of critical thinking also mutate, shift, and change course; the cluster of critical responses to capitalism that have circulated in the twentieth century (anticolonialism, anarchism, socialism, the multitude, the undercommons, punk, critical race theory, critical ethnic studies, and so forth) have also transformed themselves from identitarian pursuits grounded in the histories of exploitation and oppression, to new understandings of solidarity, commonality, and political purpose.

The current critique of feminism, moreover, is implied in lots of different venues. For example, in new philosophical projects like Object Oriented Ontology, mostly male-bodied theorists investigate the relations between subjects and objects and seek to decenter the human subject from accounts of object life without recognizing that this has been a central concern in feminist theory and queer theory for many years. Or in contemporary Gay Studies scholarship, gay men reach back to a time before AIDS and before lesbian feminism to consider the good old days of promiscuous sex and cruising, implying in the process that we have thought way too much about the politics of gender and not enough about the materiality of sex cultures. In much of this work, “feminism” is shorthand for a “stuck” or arrested mode of theorizing that clings to old-fashioned formulations of embodiment and returns us to the bad old days of gender stability, sex negativity, and political correctness. All of these backlashes gain force despite the continued popularity of Judith Butler’s work and the poststructuralist forms of feminist critique that she has authored and inspired!

In what follows, I elaborate on my Gaga manifesto to make clear how, like Preciado, I no longer believe in or remain invested in a feminist or a queer politics organized around norms and their disruption, or one concerned with binary and transhistorical formulations of “men” and “women,” “hetero-“ and “homo-” sexualities; but, unlike Preciado, I do not believe that the triumph of global capitalism is the end of the story, the only story, or the full story. So, dear readers, please receive this manifesto as an attempt to measure the new genders and sexualities that emerge within subcultural spaces against the new forms of “punk capitalism” described by Preciado, which seem to reterritorialize such new forms of life almost as soon as they emerge. In the hopes that a few disruptive forms fail to be reabsorbed into the global marketplace, I advocate for an anarchistic relation to being, becoming, and worlding.

1. Embrace the Impractical!

A practical scheme, says Oscar Wilde, is either one already in existence, or a scheme that could be carried out under the existing conditions; but it is exactly the existing conditions that one objects to, and any scheme that could accept these conditions is wrong and foolish. The true criterion of the practical, therefore, is not whether the latter can keep intact the wrong or foolish; rather it is whether the scheme has vitality enough to leave the stagnant waters of the old, and build, as well as sustain, new life. In the light of this conception, Anarchism is indeed practical. More than any other idea, it is helping to do away with the wrong and foolish; more than any other idea, it is building and sustaining new life.

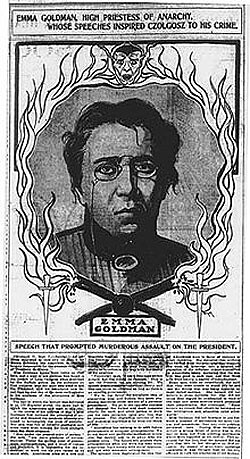

—Emma Goldman, “Anarchism: What It Really Stands For” (1910)

Responding to the idea that anarchism is impractical, that it advocates the use of violence and that it is dangerous, Emma Goldman asks what we actually mean by practicality and argues for an epistemological break with old ways of thinking. In the essay “Anarchism: What It Really Stands For,” she builds on Oscar Wilde’s reminder that what counts as practical is simply anything that can be carried out under already existing conditions. What is practical, in other words, is limited to what we can already imagine. This opens up the realm of the impractical as a space of possibility and newness. What is impractical, Goldman proposes, could become practical if existing conditions shift and change. Above all, change should break with the stagnant, with what can already be imagined, in order to access and embrace “new life.”

My book Gaga Feminism: Sex, Gender and the End of Normal made the claim that the “existing conditions” under which the building blocks of human identity were imagined and cemented in the last century—what we call gender, sex, race, and class—have changed so radically that new life can be glimpsed ahead. Our task is not to shape this new life into identifiable and comforting forms, not to “know” this “newness” in advance, but rather, as Nietzsche suggests, to impose upon the categorical chaos and crisis that surrounds us only “as much regularity and form as our practical needs require.”7

In our sense of new modes of embodiment and identification engineered by technological innovation and situated within new forms of capitalism, Beatriz Preciado and I share a common theoretical project. In Gaga Feminism, I examined symbols of change like the pregnant man, Lady Gaga, and gay marriage, not to mention new queer families, artificial reproduction, sperm banks, and new forms of political protest, to say that the revolution predicted and explained by Shulamith Firestone in The Dialectic of Sex in 1970 had come and gone! Using Marxism as a model for the structure of her feminist revolution, Firestone claimed that if the ability to technologically produce life separate from the female body became possible, then “the tyranny of the biological family would be broken.”8 Since the categories of male and female depend so heavily upon reproductive function, the argument goes, then the separation of childbirth from any essential link to female embodiment would necessarily change the relations of dependency between men and women; shift the centrality of maternity within both the definition of womanhood and cultural understandings of childrearing; and, finally, cause the nuclear family to collapse, allowing for new relations to emerge between adults and children.

Gaga Feminism claims that the existence of sperm banks, artificial reproduction of life, surrogacy, the push for gay marriage, and new arrangements of kinship and households—and not to mention the high rates of divorce—give evidence that the revolutionary conditions for gender transformation have arrived. Of course, this is not to say that “women” have been liberated from their traditional responsibilities for childrearing or domestic labor; indeed, poverty in the US disproportionately afflicts single women struggling to make a living while raising children. Preciado describes something similar in Testo Junky when she speaks of new configurations of masculinity and femininity within a global porno marketplace where the currency is pleasure and the labor of producing that pleasure is mostly shouldered by female-bodied people. Describing an order of power that is structured via the orgasm—this is what Preciado calls “potential gaudendi”—she writes: “Femininity, far from being natural, is the quality of the orgasmic force when it can be converted into merchandise, into an object of economic exchange, into work.” In other words, femininity no longer describes the cultural norms associated with living in a female body or even a physical proximity to the capacity to give birth; rather, femininity refers to a mode of labor, the production of pleasure, and a bodily relation to reproductive technologies.

By implication, Preciado claims, “heterosexuality” is therefore a “politically assisted procreation technology.”9 Her claim about heterosexuality is both humorous and deadly serious. Heterosexuality has in fact been reduced to precisely this configuration of labor, legitimacy, and logistics. Far from being a “natural” attraction between “opposites,” heterosexuality is a state-organized and state-sponsored form of reproduction. Since the alibis for the centrality and hegemony of heterosexuality have faded away (these alibis in the past have been provided by religion, science, and claims on “nature”), we can finally see heterosexuality, and by implication homosexuality, for what it actually is—state-approved intimacy. Now that, in some cases, gay and lesbian partnerships have also been granted state recognition in return for conforming to marital norms such as monogamous coupled units accompanied by parenthood, the whole edifice of the homo/hetero binary described so well by Eve Sedgwick and others in the late twentieth century crumbles. Under such conditions, we need a new politics of gender.

Gaga Feminism proposes that we are in dire need of a new politics of gender capable of addressing the contemporary pressures and values that we project onto gendered bodies and functions. And, while many people have objected to both terms of my book’s title—namely Gaga and Feminism—and to my sense that anarchism may be worth revisiting, I continue to build upon the traditions that these terms name, refusing the idea that any notion of change or transformation that we may conjure is naive, misguided, or already coopted. I refuse also the hierarchy within academic production whereby those who draw maps of domination are cast as prophets and geniuses and those who study subversion, resistance, and transformation are seen as either dupes of capitalism who propose popular culture as the cure for our mass distraction, or cast as inadequate theorists who have not read their Foucault, Deleuze, or Marx closely enough!

A new era of theory has recently emerged—we might call it “wild theory”—within which thinkers, scholars, and artists take a break from orthodoxy and experiment with knowledge, art, and the imagination, even as they remain all too aware of the constraints under which all three operate. As Lauren Berlant explains in her latest book Cruel Optimism, we hold out hope for alternatives even though we see the limitations of our own fantasies; she calls this contradictory set of desires “cruel optimism.” After showing us its forms in our congested present—fantasies that sustain our attachments to objects and things that are the obstacle to getting what we want—Berlant, remarkably, turns to anarchy, arguing that anarchists enact “repair” by recommitting to politics without believing either in “good life fantasies” or in “the transformative effectiveness of one’s actions.”10 Instead, the anarchist “does politics,” she says, “to be in the political with others.” In other words, when we engage in political action of any kind, we do not simply seek evidence of impact in order to feel that it was worthwhile; we engage in fantasies of living otherwise with groups of other people because the embrace of a common cause leads to alternative modes of satisfaction and even happiness, whether or not the political outcome is successful. Here we can see how the embrace of the impractical proposed by Oscar Wilde by way of Emma Goldman plays out!

But what is “wild theory”? And what does it want? In some ways, wild theory is failed disciplinary knowledge. It is thought that remains separate from the organizing rubrics of disciplinarity. It is philosophy on the fly. It is also a counter-canonical form of knowledge production. Berlant’s archive in Cruel Optimism, for example, is wide and varied. It includes both canonical material, performances, stories, and art projects that may not be known by her readership and that therefore require a certain amount of context and explanation. In addition to this wild archive, Berlant produces idiosyncratic methodologies that are born of a desperate desire to survive rather than a leisurely sense of thriving. The desperation that produces “cruel optimism,” according to Berlant, is born of a “crisis ordinariness,” a mode of living within which we experience life more as “desperate doggy paddling than like a magnificent swim out to the horizon.”11 “Desperate doggy paddling” describes a wild methodology within which we are less preoccupied with form and aesthetics (the “magnificent swim”), less worried about a destination (the horizon), and more involved in the struggle to stay afloat and perhaps even reach the shore, any shore.

For Preciado, wildness is also very much a part of the project of survival in a pharmacopornographic era. The testosterone s/he takes, partly as a body experiment and partly as a mode of gender adjustment, creates in her/him a rush, a clarity, energy, and vision. When he is in the grips of its effects, she sees clearly that the body is not a platform for health, a grid of identifications, a mechanism for desires that get produced or repressed depending upon different regimes of power that hold it in their grip. The body is “pansexual” and “the bioport of the orgasmic force,” and as such the body is a “techno/living system” within which binaries have collapsed.12 The self is no longer independent from a system that it both channels and represents. These are wild theories in every sense: they veer off the straight and narrow pathways of philosophy and thought and they make up vocabularies for the new phenomena that they describe at breakneck speed. Each book approaches the challenge of living, of being, and of dying in a world designed not to enhance life but merely to offer what Berlant calls “slow death.”

But is that all there is? Slow death, bare life, sexual capital? What else can the wild bring us? Does anything escape these forms of living and dying? Berlant hints towards alternatives throughout her book, countering exhaustion with “counter/absorption,” globalization with anarchy. Wild theory lives in these spaces of potentiality even as institutionalization seeks to blot it out.

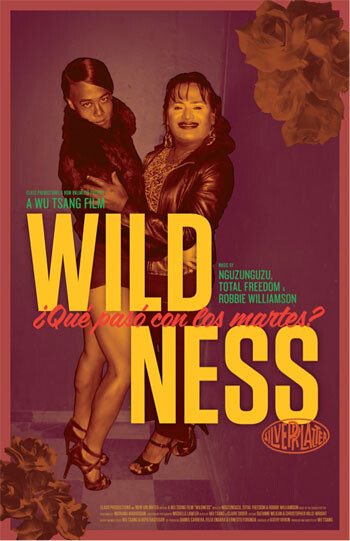

A brilliant rendition of the elemental struggle between, on one side, wild thought and wild practices, and on the other side, the canny force of institutionalization, can be found in Wildness, a documentary film by Los Angeles-based artist Wu Tsang (co-written with Roya Rastega). The film presents the story of “Wildness,” a short-lived party hosted by Tsang and his collaborator Ashland Mines, which took place on Tuesday nights at a club called The Silver Platter in the Rampart neighborhood of Los Angeles. On other nights, the club was home to a community of mostly Mexican and Central American gay men and transgender women. When “Wildness” begins to take over and brings unwanted publicity to The Silver Platter, both communities are forced to reckon with the ways in which the competing subcultural spaces cannot coexist, and with the possibility that one will swallow the other. “Wildness” set out to conjure and inhabit a cool, multiracial space where performance subcultures could open up new utopian forms of life.

The utopia that Wildness sets out to document can be understood in the terms that José E. Muñoz lays out for queer potentiality in Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity. Muñoz articulates utopia not as a place but as a “horizon,” as a “mode of possibility,” a queer future that is “not an end but an opening.”13 He also locates the horizon in temporal terms as “a modality of ecstatic time” and, referencing Ernst Bloch, as an event that is not yet here.14 Queerness, for Muñoz, is a way of being whose time has not yet come, for which the conditions are not yet right, but which can be anticipated through fresh blasts of queer performance. This sense of a queer community that is not yet here makes the project of “Wildness” legible. What Wu and Ashland set out to do by opening up space for alternative life anticipates another way of inhabiting urban space in which the small success of one local and subcultural scene does not have to displace another one.

Wildness invests deeply and painfully in the idea of alternative space, wild space, but also acknowledges how quickly such a space is reincorporated into relentless forms of development.

2. Start a Pussy Riot

A new protest politics have emerged in the last three years in the wake of financial disaster, economic meltdown, the waning of the nation-state, and the rise of transnational corporate sovereignty. Some of these protests have blended art and artfulness in an attempt to escape new police tactics, like kettling, and to evade media narratives that contain the unruly energy of the riot into a tidy story about looting and greed. At a time when the very rich are consolidating their ill-gotten gains at the expense of the growing numbers of the poor, the dispossessed, the criminalized, the pathologized, the foreign—the deportable, disposable, dispensable, deplorable mob—at this time, we should start to talk about anarchy. When the state is actually the author of the very problems it proposes to cure—lack of public funds, low rate of education and health care, treating everything from governance to education as a business, no redistribution of wealth, homelessness—we need to seek alternatives to the state. When the church has more power than the people, when the military gets more funding than schools, when white people get away with murder and people of color linger in overcrowded prisons for minor crimes like the possession of marijuana, we need to seek alternatives to law and order.

The cultivation of such alternatives occurs in a variety of cultural sites: low and high culture, museum culture, and street culture. This takes the form of participatory art, ephemeral parties, and imaginative forms of recycling and different relations to objects, economies, and the environment. As we seek to reimagine the here and now through anarchy, can we think about it as queer and hold it open to new forms of political intervention?

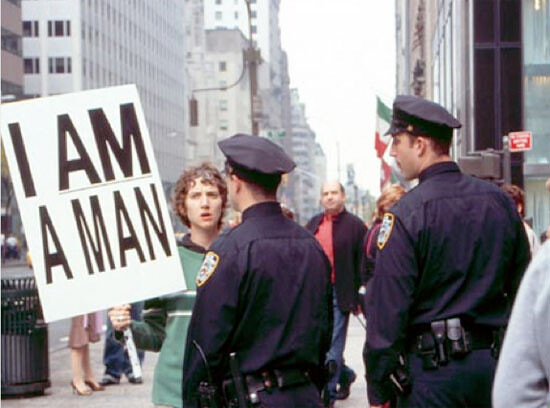

Artist Sharon Hayes variously intervenes in the silent, random, and anonymous vectors of the public sphere by delivering speeches about love in public space, or by positioning herself within the public sphere as a sign that demands to be read. Hayes’s performances and her aesthetic protests may use some of the same symbols and signs as a protest march, but they are not congruent with it either in goals or in form. Less like an activist and more like a hustler, a billboard, a busker, or a panhandler, Hayes forces herself upon passersby to give them her message and to often recruit them to give voice.

In In The Near Future, Hayes invites people to come and witness her reenactment of moments of protest from the past, like a 1968 Memphis Sanitation strike restaged in NYC at an ACT UP protest site, a restaged ERA rights march, and the revisiting of an antiwar protest. Hayes’s events were staged in four different cities where the audience was invited to witness her holding a protest sign in public space and to record and document the event. Presented as photographic slide installations in institutional spaces, Hayes’s documentation of these protest-events are not “literal reenactments.” Instead, they function as citations of the past on behalf of a possible future, a notion that echoes Muñoz’s theory of queer utopia. For both Hayes and Muñoz, the future is something that queers cannot foreclose, must not abandon, and that in fact presents a temporal orientation that enfolds the potentiality of queerness even as it awaits its arrival. Hayes’s events call for a new understanding of history, make connections between past and present eruptions of wild and inventive protest, and allow those moments to talk to each other in order to produce a near future. She reminds us that politics is work between strangers and not just cooperation between familiars. She directs our attention away from the charisma of visual spectacle and towards a more collaborative and generous act of listening.

In a painting of Pussy Riot, Berlin-based artist Kerstin Drechsel captures the queerness of our moment of riot and revolt. Drechsel’s rendering of the masked Russian punk feminist band, currently serving jail time for staging a protest in Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Savior where they critiqued the Orthodox Church leader’s support for Putin’s presidential campaign, is spare and powerful. It reminds us of how often anarchy has taken the form of a feminine punk refusal rather than a masculinist violent surge. I outline some of these logics in my chapter on “Shadow Feminism” in The Queer Art of Failure, where I revisit feminist performance art from the 1970s as well as anticolonial literary texts to outline alternative modes of resistance that are grounded in refusal and tactics of self-destruction rather than in engagement and self-activation.15 Within such a framework, performances by Marina Abramovic and Yoko Ono and the novels of Jamaica Kincaid become legible as feminist practices.

The example of Pussy Riot—the group, the painting, the action, and its recreation around the world—gives rise to the question of what new aesthetic forms accompany these suddenly highly visible manifestations of political exhaustion and outrage. Pussy Riot offers hope for new forms of protest. Can we find an aesthetic that maps onto anarchy and stages a refusal of the logic of “punk capitalism”? What is the erotic economy of such work?

There are several reasons why people turn away from anarchy as a political project even when the state is inadequate and corrupt. Some see anarchy as either scary or naive. They fear that it will unleash the terror of disorder and chaos upon society, a chaotic power that the state and capitalism supposedly keep at bay. Politically speaking, anarchy has also been cast as outmoded because the nation-state has given way to transnational capital and the global movements of elites and goods. It is true that capital has gone global and is no longer maintained only through national structures, but this does not mean that the political form of the nation-state has given way to more global forms of rule. As long as most of us experience our political subjectivities through the nation-state, we need to continue imagining alternatives to it.16

“Hierarchy is chaos!” says the well-known anarchist slogan. But chaos is a matter of perspective rather than an absolute value. We often see capitalism and state logics of accumulation and redistribution of wealth as natural or even intuitive. We tend to characterize them as orderly systems, yet we could easily argue that the nation-state produces plenty of chaos for the subjects it rules, those it abandons, and those it incarcerates. Capitalism uses chaos on its own behalf while warning subject-clients of the dangers of abandoning market economies in favor of other models of exchange, barter, and economic collaboration.

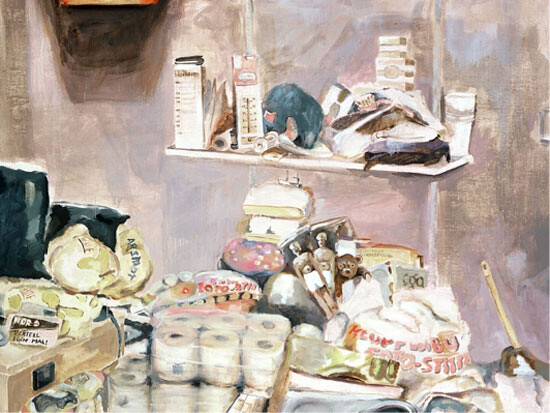

In an extraordinary body of work, artist Kerstin Drechsel explores the sexual entropy of the everyday and the chaos inherent to capitalism. Drechsel refuses the neat division between a chaotic world ordered by capitalist modes of production and the chaos of anarchy that capitalism supposedly holds at bay. Drechsel’s work recognizes that capitalism too is chaotic and disordered, that the world we live in tends towards breakdown, and that the state simply manages and marshals chaos for capital accumulation and biopower. Anarchy is thus no more oriented to chaos than capitalism.

In the series Unser Haus, Drechsel confronts messiness directly in paintings of explicitly junky domestic interiors. In some spaces, the books and the paper overwhelm the spaces that should contain them; in others, the materials we use to clean away the traces of dirt—toilet paper, for instance—become waste itself.

In this series, an aesthetic of disorder prevails. The paintings dare the viewer to take them home, to hang them on the wall. They threaten to mirror back to the viewer/owner a desperate image of the disorder that the house barely keeps at bay and that this art encourages. The paintings of messy interiors taunt the collector and liken the collecting of art to the collecting of things, useless things, stuff. They menace and snarl; they refuse to be the accent on a minimal interior; they promise to sow disorder and shove any environment firmly in the direction of anarchy. In Drechsel’s work and world, the human is just a small inhabitant of a literal wasteland of objects and things. Her world is chaotic and she herself is dedicated to trying to wax, slim, domesticate, and train. Drechsel is working hard towards a conformity that is always just out a reach. And just as the human-like dolls in her work seem to be reaching for some kind of pleasure, space, or activity that will offer liberty, so the object world keeps threatening to overrun dolls, humans, homes, and hierarchies with its own form of riot.

In the Wärmeland series, Drechsel places hand-made Barbie dolls in dollhouse settings and manipulates them pornographically both to reveal the sexuality that the dolls represent, and to remake the meaning of the domestic and of desire itself. Creating alluring sex scenes with the Barbies and then placing the two lusty bodies in candy-colored environments that make perverse use of Barbie accessories, Drechsel draws out not only the desires we project onto the doll bodies, but also the much more compelling set of desires that draws us to the accessories, to the backdrops, and to the objects in our worlds. As we peer into the dollhouses, we begin to see them as prisons and domestic cages, but also as film sets and stages for strange miniature sexual dramas.

Wärmeland is reminiscent of the Barbie Liberation Organization (BLO), a 1990s group of artists and activists who engaged in culture jamming by switching the voice boxes of Barbie and Ken dolls in toy stores around the country. While previously a Barbie may have been programmed to say, “I am not so good at math,” after the BLO liberated it, it said, “Vengeance is mine!”

3. Be Fantastic! Charming for the Revolution!17

How do we charm and seduce for the revolution? Let’s learn from one of the most charming revolutionary figures to ever grace cinema: Wes Anderson’s animated genius, Fantastic Mr. Fox. Fantastic Mr. Fox, when watched closely, gives us clues and hints about revolt, riot, fugitivity, and its relation to charm and theft. The film tells a simple story about a fox who gets sick of his upwardly mobile lifestyle and goes back to his roots. He lives a respectable life with his wife and his queer son by day, but by night he steals chickens from the farmers down the hill. When the farmers come for him, Mr. Fox asks his motley woodland crew of foxes, beavers, raccoons, and possums to retreat with him to the maze of tunnels that make up the forest underground. And in scenes that could be right out of The Battle of Algiers, the creatures go down to rise up: they thwart the farmers, the policemen, the firemen, and all the officials who come to drive them from their homes and occupy their land.

We learn many things in Fantastic Mr. Fox about being charming, being fantastic, and creating revolt. But the best and most poignant scene comes in the form of a quiet encounter with the wild at the end of the film. In this scene, Mr. Fox is on his way home after escaping from the farmers once again. As he and his merry band of creatures turn the corner on their motorbike with sidecar, they come upon a spectral figure loping into their path. Mr. Fox pulls up and they all stand in awe. They watch as a lone wolf turns and stares back at them. Mr. Fox, ever the diplomat, declares his phobia of wolves and yet tries to communicate with the wolf in three languages. When nothing works, he tries gestures. With tears in his eyes, Mr. Fox raises a fist to the wolf on the hill and stares transfixed as the wolf understands the universal sign of solidarity and raises his own fist in response, before drifting off into the forest. This exchange, silent and profound, brings tears to Mr. Fox’s eyes precisely because it puts him face to face with the wildness he fears and the wildness he harbors within himself.

Whether you see the scene as corny or contrived, odd or predictable, generic or fetishistic, you know that you have witnessed a moment that Deleuze might call “pure cinema.” This scene, in other words, draws us into the charisma of the image; it speaks a visual grammar that cannot be reduced to the plot and it enacts a revolutionary instance that we, like Mr. Fox, cannot put into words. And because we are confronted with the possibility of a life beyond the limits of our comprehension, because we see the very edge of the framing of knowing and seeing, and because we see Mr. Fox reaching for something just out of reach, we, like him, are changed by the chance encounter.

The wild here is a space that opens up when we step outside of the conventional realms of political action and confront our fears; it rhymes with Muñoz’s sense of queer utopia and manifests what Fred Moten and Stefano Harney call the power of the “the undercommons.”18 The wild and the fantastic enter the frame of visibility in the form of an encounter between the semi-domesticated and the unknown, speech and silence, motion and stillness. Ultimately, the revolutionary is a wild space where temporality is uncertain, relation is improvised, and futurity is on hold. Into this “any instant whatsoever” (Deleuze) walks a figure that we cannot classify, that refuses to engage us in conventional terms, but speaks instead in the gestural language of solidarity, connection, and insurrection.

The wild projects I am making common cause with tend to anticipate rather than describe new ways of being together, making worlds, and sharing space. As Emma Goldman said of anarchy in 1910, the project for creating new forms of political life starts with the transformation of existing conditions. It is urgent and necessary to put our considerable collective intellectual acumen to work to imagine and prepare for what comes after. The wild archive that I have gathered here is made up of the improbable, impossible, and unlikely visions of a queer world to come. Change involves giving and risking everything for a cause that is uncertain, a trajectory that is unclear, and a mission that may well fail. Fail well, fail wildly.

“Gender Talents: A Special Address.” See →.

Beatriz Preciado’s interventions are taken from her forthcoming book Testo Junky: Sex, Drugs, and Biopolitics in the Pharmacopornographic Era, trans. Bruce Benderson (New York: The Feminist Press, 2013).

See my Gaga Feminism: Sex, Gender and the End of Normal(Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 2012).

Testo Junky, 33.

Ibid., 35.

Ibid., 82.

Friedrich Nietzsche, The Will To Power (New York: Vintage Books, 1968), 278.

Shulamith Firestone, The Dialectic of Sex: The Case for Feminist Revolution (New York, NY: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 1970), 11.

Testo Junky, 46–47.

Lauren Berlant, Cruel Optimism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011), 260.

Ibid., 117.

Testo Junky, 41.

José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (New York: NYU Press, 2009), 99, 91.

Ibid., 32.

Judith Jack Halberstam, The Queer Art of Failure (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011).

Indeed, currently many collectives and radical thinkers have been producing manifestos. In addition to The Invisible Committee’s The Coming Insurrection (2009), Italian Marxist Franco “Bifo” Berardi has written The Uprising: On Poetry and Finance (2012), and Fred Moten and Stefano Harney have collaborated on The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study (2013).

“Charming for the Revolution” is both the name of a short film by Renate Lorenz and Paulina Baudry, and the title of the congress on art and gender politics of which “Gender Talents: A Special Address” formed a part. The congress was curated by Electra and Tate Film.

Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study (Wivenhoe, UK: Minor Compositions, 2013).

Category

Subject

I would like to thank Carlos Motta for inviting me to the conference that inspired this essay and for working with me so closely to make it a little less wild and a little more thoughtful.