I don’t know if Pasolini ever visited the United Kingdom. Maybe yes, maybe no. I don’t really care. I would like to talk about Pasolini in Tottenham. I want to question the sensibility of the poet of the mid-twentieth-century Roman borgate from the point of view of a violent rebellion of lumpenproletarians that took place in the English suburbs in August 2011.

The visions and predictions that we find in his writings and films are good starting points for a discussion about what happened in the streets of Tottenham and Peckham, and also about what is going to happen in the coming months and years all over Europe, in the insurrection that has already started and that will continue to rage everywhere in the Old Continent—a continent that is turning into a region of violence and misery thanks to neoliberal politics, financial dictatorship, and the ignorance and dogmatism of the European ruling class.

Meeting Pasolini

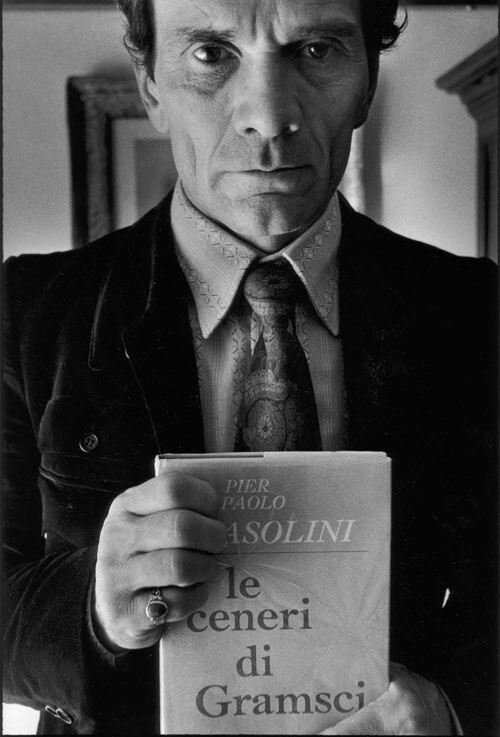

I met Pasolini in 1965, or maybe 1966, when as a schoolboy I went to see The Gospel According to Matthew with Professor Corrado Festi, a blind man who taught philosophy in the high school where I studied. Professor Festi was a libertarian communist who brought a student or two to the movies with him because he needed someone to explain what we were seeing, so that he himself could see.

I met Pasolini again in the year 1968, after the Valle Giulia riots, when for the first time the students did not run away, but instead reacted against the violence of the police. In Valle Giulia, Pasolini wrote a poem—a bad poem, I believe: rancorous and sour, without light or irony.

But it was interesting nonetheless. The poem’s title was Il PCI ai giovani! (The Italian Communist Party to the young!), but it came to be widely known by the title Vi odio cari studenti (I hate you dear students) only because the magazine L’Espresso printed the poem with this alternate title. In the poem, Pasolini accuses the students of being the power-hungry offspring of rich parents who fight against their parents in order to wrest power from their hands. Simultaneously, he declares his love for the policemen, who are young sons of farmers and workers. Old populist rhetoric, I must say. Paccottiglia (junk), as we say in Italian.

Then I met Pasolini for the third and final time at the house of a mutual friend, Laura Betti, one night in 1973. I greeted that unsmiling harsh man without much sympathy. In those years, he was publishing “Letters to Gennariello” in the pages of Il Corriere della sera, and the portrait he was drawing of the young Neapolitan proletarian seemed fake to me.1 I was dealing with young proletarians from Naples and other Southern Italian cities, and their sensibilities seemed very different from Pasolini’s Gennariello. The young southerners I met in the Northern Italian factories were no less old-fashioned and instinctive than Pasolini’s Gennariello, but they were much sharper and more sophisticated. They were the migrant workers assembled in the factories of Milan and Turin, the driving force behind the new wave of autonomous struggles against capitalist exploitation and industrial work. They resembled the young Fiat worker described by Balestrini in his novel Vogliamo tutto (We want everything), published some years before.

Gennariello came out of an old populist mythology that didn’t speak to me in the least.

Words and Visions

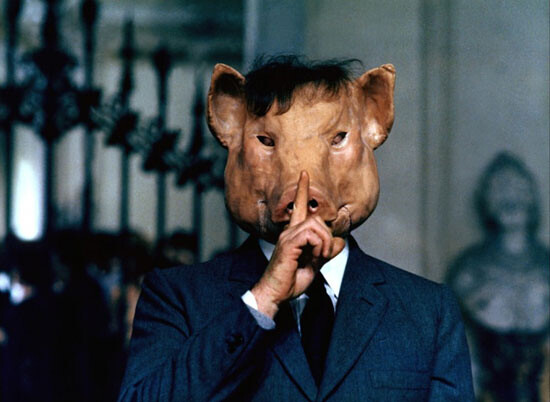

When we look at Pasolini’s work, when we read his novels and his poems and his countless interviews and articles, and when we watch his movies and documentaries, we sometimes feel we are getting lost in a labyrinth of paradoxes. I have tried to make sense of his paradoxical judgments and opinions, of his idiosyncrasies, passions, and aversions. The general conclusion that I have reached is this: when he writes, when he speaks, when he ideologizes, Pasolini is essentially a reactionary and a conformist disguised as a provocateur. But when it comes to his works that use images, Pasolini is a visionary, almost a prophet, and he is able to see much further than anybody else. Although a bad poet and an old-fashioned ideologue whose knowledge of Marxist philosophy was quite poor, Pasolini was a man of extraordinary vision.

In my opinion, he did not understand the meaning of the student movement of ‘68. Many of the students who took to the streets in that year, in Italy and France and elsewhere, were probably the offspring of bourgeois parents. Many were born to professionals and petit bourgeois, but others came from working-class families, although access to universities was still limited for the children of workers back then. But sociological considerations such as these do not really get to the heart of the matter.

The meaning of the upheaval that shook the world in the year 1968 can only be grasped by looking at the long-term recomposition of labor that took place during that period, transforming the technological structure of the production process. That movement marked the initial emergence of cognitive work, which in the following decades became the main engine of production. The alliance between students and industrial workers was not a rhetorical exhibition of solidarity, but a sign of the increasing productivity and interdependence of industrial labor, the application of new technologies, and the prospect of liberating social time from the slavery of labor.

Pasolini was totally wrong in his appraisal of the student movement because he missed the crucial point: the social origin of students was not the important thing as much as the new role that cognitive work was destined to play in the transformation of capitalist production and in the political composition of the working class.

Gennariello Fake and True

After 1968, Pasolini’s approach to the movement changed: he was pushed by the very force of events to acknowledge the proletarian character of the movement, and he drew close to Lotta Continua (Continuous Struggle), a leftist organization that mixed Marxism, Maoism, and anarchism with a generous helping of Christian radicalism. Together with Lotta Continua, Pasolini made a movie entitled 12 Dicembre. It is not hard to understand Pasolini’s attraction to Lotta Continua. “The priority of these young militants is passion and sentiment,” he said. And a certain degree of theoretical inaccuracy—what we call “pressapochismo” (carelessness)—helped. Lotta Continua was not a political organization, but a climate of mind, a feeling which sometimes verged on populism. A broad feeling of love for the people, the destitute, and the dispossessed was the common ground of Lotta Continua and Pasolini.

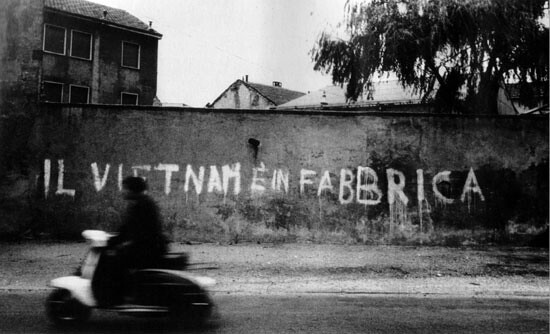

In the “Letters to Gennariello,” this love for the poor melded with a mythology about the supposed authenticity of the young, pre-modern Neapolitan young man the writer wanted to protect from the contamination of consumerism and modern coarseness. But this mythology was empty and fake: the true Gennariellos in those years were not so naive and unsophisticated as Pasolini liked to imagine. In 1973, young workers from Southern Italy occupied the Fiat factory in Turin, and in 1977 they launched a general insurrection that reached its peak in Rome and Bologna in the spring of that year.

Having been killed in November 1975, Pasolini did not see the explosion of 1977. So we cannot say if he would have recognized in the insurgents of Rome and Bologna the brothers of his Gennariello. I don’t think so. Rather, I think Pasolini would have joined the Stalinists of the Italian Communist Party (who after ‘89 converted to neoliberalism, but in ’77 still worshipped the supreme authority of the State) in condemning the delirium and madness of Mao-Dadaists and Indiani Metropolitani.2 Who knows?

Fascism Belongs to the Future

I think that Pasolini’s statements about the meaning of ‘68 are wrong. He totally misunderstood the historical process encompassing the student upheaval. But on some crucial points, Pasolini was able to see (and I mean to see) things that we missed completely.

The main mistake of the Italian student movement, and the mistake of the intellectual groups that were the progressive soul of that movement—my personal mistake and the mistake of Potere Operaio (Workers’ Power), the group I was part of—was exactly in our thinking that fascism belonged to the past. We thought that the enemy of students and workers was the neo-capitalist, social-democratic bourgeoisie. Fascists still existed, of course, but they were considered throwbacks from the dark past of Mussolini, isolated criminals who the ruling class could use at its convenience to scare the popular movement, to divert the attention of the workers from the struggle against capitalist exploitation.

This is why the movement launched self-defeating campaigns of antifascismo militante (militant antifascism) that only managed to fall into the trap of violence—hammering at some black-clad idiots and being hammered by them. We were dead wrong, because fascism is not something that belongs to the past. Fascism belongs to the future. This is what Pasolini clearly saw, although he was unable to explain it in plain theoretical words. Pasolini rightly linked fascism to sexual humiliation, consumerism, ignorance, rage, and ugliness. All of these have been on the rise during the years of neoliberal dictatorship. Ugliness is everywhere—in cities ravaged by speculation, in bodies wasted by exploitation and loneliness, in ubiquitous advertising billboards and television screens.

It is not easy to say what fascism means, but I humbly propose that fascism is a pathology of identity—a pathology hitting those who are too weak to accept the idea that identity is ever-changing and multifarious, and too frightened by their own uncertainty and ambivalence. Pasolini was able to predict the spread of this ambivalence, this fear, this frailty, and to foresee the epidemic rage that was destined to emerge from this.

Power’s Worshippers

Pasolini saw better than I and my fellow students and workers in the autonomous movement the personal destiny of the ‘68ers. Let’s go back to coarse poem titled Il PCI ai giovani!, where he expresses his contempt for the students of the movement and his love for the poor young policemen. He says that those young people, those students, were only fighting for power, were only aiming at taking power from the hands of their parents.

It’s foolish to believe that this accusation applies to the entirety of the movement. But a large part of the social body that we called “the movement” has shown that Pasolini was right on this point. I’m thinking particularly of those people who were part of the pro-Soviet Communist Party, and also those who were part of the many Stalinist-Maoist parties. Many of the intellectuals and militants who were followers of the Leninist Faith (the faith in power) have since converted to the Neoliberal Faith. Richard Pearl and Massimo D’Alema, André Glucksmann and Giuliano Ferrara, William Kristol and Vladimir Putin—all of them have this in common. In their youth, they accepted and justified the concentration camps of Joseph Stalin, the crimes and lies and oppression of the Soviet nomenklatura. All of them accepted and hailed the proletarian dictatorship as a step towards the bright future of socialism.

They were Maoists and Stalinists and Trotskyites—in other words, Leninists. And all of them subsequently turned into neoliberal worshippers of capitalist competition and capitalist growth, accepting and justifying the crimes and lies of neoliberal rule. Why is this? Why did the same intellectuals who in ’68 waved the red book of Mao go on to publish, ten or fifteen years later, articles railing against egalitarianism and extolling the glories of capitalist democracy and infinite growth? The answer lies, of course, in their miserable personal biographies—as Pasolini rightly perceived. But biographical facts are not enough to understand their betrayal, because their betrayal is not only an act of moral baseness (which it certainly is). It is also an act of intellectual cohesion.

There is a rationale to their baseness. All the names I’ve listed above are names of arrogant climbers with unimpressive intellects, but their common denominator is this: all of them believed in the Dialectical Creed. Therefore, they were convinced that the working class was destined to win. In the dreams of young Stalinists and Trotskyites and Maoists, the working class was destined to win and exert power through violence, dictatorship, and terror. When these intellectuals realized that things were not going according to plan, they did not discard the Dialectical Creed: Reason will be Real, and Reality will be Rational. They quite simply changed sides. For someone who believes that History is dialectical, the winner is always right. His mind always follows the same paradigm, and he always trusts in the same dogma: Only Power Is Real. This is the philosophical principle of the Leninist intellectuals. This is their moral North Star.

Pasolini in Tottenham

But they are wrong. What is called “reality” refers not only to what exists, but also to the realm of the possible. What exists as imagination, what exists as a tendency in the concatenation of social intelligence, is real—although the existing power of capitalism is acting to block the possible from emerging. What is possible may be killed, repressed, or forced back, but it is real.

Being arrogant simpletons, these second-rate intellectuals named Glucksmann and Ferrara and Pearl and D’Alema could not really perceive the depth of the social and cultural transformation that they attempted to govern by shifting from the side of the workers to the side of capital. They could not imagine the unpredictability of the process they simplistically reduced to a problem of winners and losers. They supported the criminal turn in the history of human evolution implemented by Thatcher and Reagan. They supported violence, financial dictatorship, and terror, and they named it “democracy.” But history is not finished, and now capitalism is in agony. Representative democracy is a bedtime story that masks the reality of financial dictatorship and war.

Now I want to go with Pasolini to Tottenham. A young man, Mark Duggan, was killed in Tottenham by police on August 4. After his death, thousands of young workers and unemployed people and students took to the streets in the suburbs of London, Birmingham, and Manchester and attacked banks and shops, stealing goods from supermarkets, setting houses ablaze, and attacking police. The British Prime Minister, quickly called back from his holiday in Tuscany, declared: they are common criminals.

I have tried to look at the four nights of rage from Pasolini’s point of view. Fascist consumerism or lumpen desacralization of consumerist rituals? Personally, I despise the priggish journalists and hypocritical intellectuals who screamed in Murdoch’s newspapers that the riots were not political events, but coarse acts of consumerist violence. During the last thirty years or so, media, advertising, and neoliberal ideologists have obsessively repeated a message to young people: life is competition, and the field of competition is consumption. The more gadgets you have, the better your life will be, even if you have to endure exploitation and humiliation every day. Now, all of a sudden, the kids have been told that they have to pay the debt accumulated by the financial class. Social spending has to be cut and there will be no jobs for young people. No wonder that people who have been promised lots of gadgets in exchange for their lives want those gadgets at any cost.

Often in Pasolini’s novels and movies, the young male body is an object of worship and contempt. Beyond its sexual undertones, this ambivalence has a political and cultural meaning: the beautiful and the criminal are joined in the same person. Think of the title character from Pasolini’s film Accattone, simultaneously innocent and sordid.

Many say that the London rioters are just looters—consumerist and violent. They forget that these young people have been shaped by an ugly human landscape produced through thirty years of competition and consumerism. Empathy has become frail, solidarity has been ridiculed and destroyed. The rioters of London have been cultivated by Murdoch’s popular magazines and TV garbage.

We should not worship this rebellion and we should not condemn it. We should be able to accept and understand its historical meaning: capitalism is morally and economically bankrupt. From within the much-needed insurrection of the precarious generation we should be able to create a new consciousness, a new self-perception based on solidarity, on the refusal of exploitation, on frugality, and on a culture of sharing: sharing production in the web-based world and sharing consumption in the city.

European Insurrection

Leftist intellectuals may despise consumerism and ersatz culture, but in my view this is not a time for moralizing. It is a time to imagine a possible social recomposition of the precarious body and the general intellect. Cognitive labor and precariousness are not separate realities. Cognitive workers are unemployed, and precarious workers are often highly educated young people whose intellectual skills are ominously underused. Cognitarians and lumpens intermingle in daily life, and sometimes they decide to go looting together.

Looting is not good, particularly when it involves the life and belongings of common people. But from looting we must move towards the liberation of the general intellect. I don’t think that all the young people who took to the streets of England on those August nights were motivated by political solidarity. I believe they were motivated by many different feelings: rage, in some cases egoistic consumerist craving, but also, in many cases, by a desire for togetherness. Insurrections are never the effect of a well-conceived project, of well-mannered intentions. Generally, insurrections start from a mix of different impulses. What matters is the ability of a minority (call them the political avant-garde, call them organic intellectuals, maybe call them schizoanalysts) to find concepts, and words, and gestures that give different people a common vision and a common understanding of the real and the possible.

In the coming months, we won’t need a political party. Rather, we’ll need a bunch of curators for the European insurrection. We don’t have to provoke the insurrection, as the insurrection is being provoked by the European Central Bank and by the cowardice and ignorance of the European ruling class. Instead, we have to introduce into the unavoidable insurrection some perception of the potency of collective intelligence, and we have to connect this perception to a desire for sociality. The general intellect is looking for the erotic and social body that it lost in the process of virtualization. Similarly, precarious life is looking for a collective intelligence that is fragmented and dispersed.

In trying to imagine Pasolini on the stage of the present European insurrection, I think that he would quote Matthew’s Gospel:

Therefore I tell you, do not be anxious about your life,

what you shall eat or what you shall drink,

nor about your body, what you shall put on.

Is not life more than food, and the body more than clothing?

Look at the birds of the air: they neither sow nor reap nor gather into barns,

and yet your heavenly Father feeds them.

Are you not of more value than they?

And which of you by being anxious can add one cubit to his span of life?

And why are you anxious about clothing?

Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow; they neither toil nor spin;

yet I tell you, even Solomon in all his glory was not arrayed like one of these.

But if God so clothes the grass of the field, which today is alive and tomorrow is thrown into the oven, will he not much more clothe you, O men of little faith?

Therefore do not be anxious, saying, “What shall we eat?” or “What shall we drink?” or “What shall we wear?”

For the Gentiles seek all these things; and your heavenly Father knows that you need them all.

But seek first his kingdom and his righteousness, and all these things shall be yours as well. Therefore do not be anxious about tomorrow, for tomorrow will be anxious for itself. Let the day’s own trouble be sufficient for the day.

I am an atheist and I do not believe that any almighty Father is in the sky. But I know the infinite potency of the general intellect, when it is governed by solidarity and affection, to be a desire free of greed. We can rely on collective intelligence: it is our Father who is on earth. It is our autonomy from any subjection—to capitalism, to the state, and to God.

Shortly before his murder in 1975, Pasolini published a series of letters addressed to an imaginary student named Gennariello, a young boy from Naples, in the Italian newspaper Il Corriere della sera.

The Indiani Metropolitani (Metropolitan Indians) were the so-called creative wing of the Italian students movement who often dressed up like Native Americans.

Subject

This essay was originally commissioned by the Office for Contemporary Art Norway (OCA) within the lecture series “The State of Things,” as part of the official Norwegian representation in the 54th edition of the Venice Biennale and it was published in the volume The State of Things (OCA and Koenig Books London, 2012), edited by Marta Kuzma, Pablo Lafuente and Peter Osborne. The State of Things publication is available in bookstores, at OCA Norway, and internationally at Koenig Books .